culture

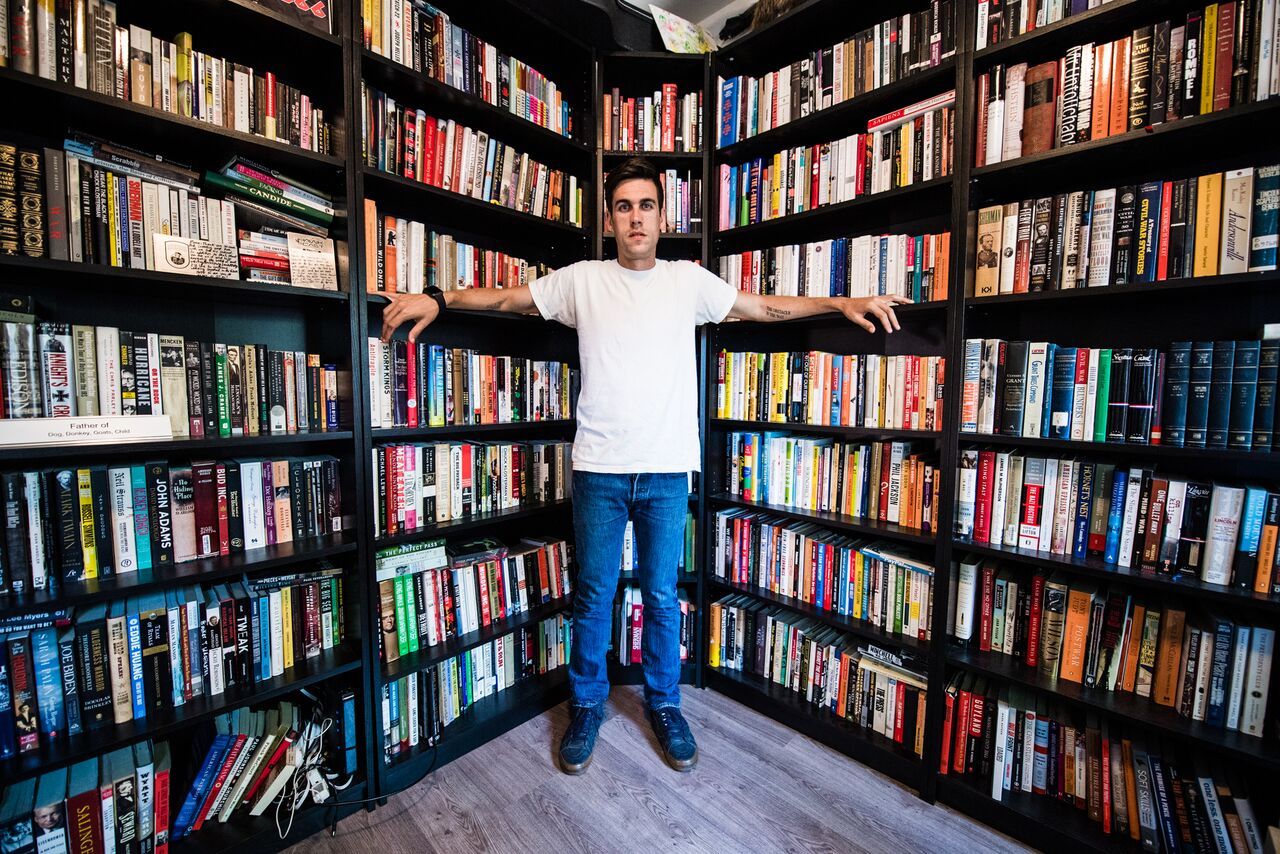

What Happened to Gawker? An Interview with Ryan Holiday

Ryan Holiday’s book 'Conspiracy' tells the story of Peter Thiel’s decade-long campaign against Gawker Media.

Ryan Holiday is the author of Trust Me, I’m Lying and numerous other books about marketing and culture. Holiday dropped out of college at 19, and by age 20 was chief marketing officer for American Apparel. His advisory firm, Brass Check, has counselled companies such as Google, TASER and Complex. Holiday’s most recent book, Conspiracy, tells the story of Peter Thiel’s decade-long campaign against Gawker Media, including his funding of the successful lawsuit against Gawker initiated by Terry Bollea, better known as Hulk Hogan. Holiday was interviewed by Stephen Elliott in November, following Holiday’s keynote address to the Athletic Business Show at the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center in New Orleans.

Stephen Elliott: I’ve been thinking a lot about deplatforming. Your new book, Conspiracy, is kind of the ultimate deplatforming story. Except instead of what normally happens, where a person is denied a venue to speak, or a celebrity loses their TV show, this is the story of an entire platform, Gawker media, being destroyed by the billionaire Peter Thiel.

Ryan Holiday: Right. What we’re describing is a billionaire setting out to destroy a media outlet he doesn’t like. That’s very scary if you’re a free speech advocate and you don’t know anything else about the case. But as you dig into it, the story gets much more complicated.

SE: How so?

RH: Gawker deliberately outed Peter Thiel as a homosexual. He was a private person who didn’t want to be outed. They had outed a number of other people as well.

Now, media outlets sort of defame and slander people all the time. They understand that the burden of proving this defamation is not only very expensive but, as far as libel goes, the standard in this county is that you have to prove it was done with reckless malice. And proving that is extraordinarily difficult. The discovery process is so onerous to both sides that these cases almost never go to trial. And anyway outing someone is not illegal. So he couldn’t do anything about it.

What Peter Thiel eventually did is discover another case that was far more egregious. Gawker outed Thiel in 2007. He waited five years to support the Hulk Hogan lawsuit in 2012, and there was no verdict until March of 2016. It’s a pretty incredible—almost Count of Monte Cristo-esque—story of revenge and, depending on where you sit, justice.

SE: We should back up for a second and point out that you and I met once before, in combat. Back in my political organizing days, I started an organization to stop American Apparel from opening a store in the Mission District in San Francisco. And you were the chief marketing officer.

RH: Yeah. This was not a store I had anything to do with or knew anything about. I got thrown into responding to what you had organized, which was a sort of grass-roots boycott/backlash movement against the store. And we ended up getting crushed. I think I was probably 20 or 21 years old and I had to sit and get yelled at by about 600 angry San Franciscans for what was probably one of the worst days of my life. In retrospect, it was completely absurd and one of my favorite stories. Basically, some rogue employee had signed this lease without reading the zoning laws. I remember a woman at the hearing saying she had been trying to open a vintage sex-toy store in the same location. I was like, “What’s a vintage sex toy? Does she mean used?”

SE: It’s funny because I personally had no problem with American Apparel. We just wanted to keep chain stores off Valencia Street. We were very good about staying on message and not talking about the brand. At the protests, there were a lot of American Apparel shirts, which led to Rush Limbaugh doing a whole segment on me.

I’d been doing a monthly reading series to raise money for progressive political candidates, so I already had an email list of socially engaged local residents. I passed the store and saw a sign in the window. It wasn’t easy to read but it said an American Apparel would be opening in 17 days. I went home and started organizing. It was like throwing a lit match in a bale of cotton. I was told it was a record turnout for a city Planning Commission meeting.

RH: There was an extraordinary amount of media coverage, driven primarily by blogs. I remember SFist and Curbed San Francisco. It was a predecessor to what we’re seeing now, which is how this sort of mob who agree with a cause or whatever can just flash active and direct incredible amounts of attention and leverage and create basically unwinable situations.

SE: How did you end up as the marketing director for American Apparel at 20 years old?

RH: My mentor Robert Greene was on the board of directors. I was his research assistant and sort of marketing person. Basically, I came in to add one project, and then another, and the next thing I knew I was running the marketing department, which I had no business running at the time. It was a dysfunctional company. But I got to do a lot of cool things and learned a lot.

American Apparel was probably the first company created by the internet and internet culture. And it was one of the first to be undone by that very same thing. The idea that it was even news that American Apparel was trying to open a store in the Mission District and then people didn’t want it there was a reflection of just how much bigger its brand was than the reality of the business. You classified it as a big box store, but Walmart probably makes more money in single cities than American Apparel did in total. The internet allows you to punch above your weight class. It also then allows you to get piled on.

SE: Conspiracy was your sixth book. You did a lot of writing in your 20s! I’ve been reading your other books, like The Obstacle is The Way, based on a quote from Marcus Aurelias, and your work on stoicism. You’re clearly a person who’s just bursting with ideas. But Conspiracy, I felt, is a level beyond your other books. Do you feel that way?

RH: It’s definitely the best writing I’ve done. It was a fortuitous situation where my personal expertise and something I was ideologically interested in overlapped with an almost unbelievable true story.

SE: It’s the first of your books where the story is the most important part, as opposed to the ideas.

RH: It was much harder to write for that reason. It was also harder because the people were alive. My other books are mostly about people who are dead. Philosophers, emperors. And the fact that I was writing about someone who just destroyed a media outlet for wronging him, that is something that loomed over the book quite a bit.

SE: How did you get so much access? Had you already written an article about the Hulk Hogan/Gawker trial?

RH: Yes. And my first book was quite critical of Gawker and laid out how they were likely to fall into something like this in the future. Starting in 2012, I wrote a media column for the New York Observer, and wrote that for almost five years. I wrote about the case not knowing I would ever do a book about it.

My writing attracted the attention of both Nick Denton, the founder of Gawker, and Peter Thiel. Nick and Peter are the two main characters in this story and having access to both of them is what made the book possible. Peter had read my media stuff and believed, based on that, he would at least be given a fair shake. Nick Denton didn’t like my media writing, but I had also written extensively about stoicism and Denton went through a calamitous sort of transformation as a result of the lawsuit and read my stoicism stuff and was a fan of that.

SE: So you had access to Peter Thiel and Nick Denton, which nobody else had.

RH: Yeah. There was a night in 2016 where I had dinner with one, then an event at the house of the other. And then breakfast with one of them the next morning.

SE: Before reading your book I had never thought of conspiracy as a neutral term. I thought of it as a performative term.

RH: People hear conspiracy and they think of things like assassination. A conspiracy is a coordinated action done in secret designed to disrupt the status quo. Peter Thiel is outed by Gawker in 2007. He finds this to be cruel and unnecessary. This is the event that launches the conspiracy.

SE: They don’t just out him, they mock him over and over again. He tries to play nice and they keep beating on him.

RH: It was basically a rude introduction to what Gawker was. They styled themselves as a site that published the things no one would else would. Sometimes, those things needed to be said and sometimes they probably didn’t. It was this sort of rebellious media company that didn’t follow the advice of lawyers and said what they wanted. They knew that nobody in their right mind sues a media outlet. For many years, this propelled them to be the sort of dark prince of the internet. They were the biggest gossip site, the most powerful and most feared.

Peter Thiel found that he didn’t like this status quo, but being outed was not illegal. He thought about what to do about it, and finally he put in motion a conspiracy. He recruits an operative, Mr. A. Mr. A hires a lawyer. A team of people come together, many not even knowing who everyone else was or the ultimate goal. Thiel begins to fund research into causes of action, funding a myriad of lawsuits against Gawker for the express purpose of destroying them and putting them out of business. Of these lawsuits, the most famous case is the Hulk Hogan sex-tape case. Hulk Hogan [Terry Bolea] had been illegally and surreptitiously recorded having sex with his best friend’s wife, and Gawker got hold of that tape.

SE: They ran it when they were asked to take it down, even when it was proven to them that he’d been recorded without his consent.

RH: They were asked to take it down and they refused. And that’s lost in the story. People don’t realize just how awful Gawker was to Hulk Hogan. They were completely unreasonable. And by the way, not only should they have taken it down for moral reasons; but on a pure copyright level they probably could have been bankrupted as well.

So Thiel is funding these lawsuits and this case sort of quietly worms its way through the legal system. Nick Denton and Gawker never really take the lawsuit seriously until it’s too late.

SE: You wrote about how Gawker had so much insurance. Their whole company was setup to be sued and to survive it and outlast people. And that’s why they’re not taking it seriously. Which is one of the most interesting lessons of the book. It shouldn’t take a billionaire to sue Gawker; a person of lesser means should have been able to sue Gawker and get justice, but was unable to.

RH: It’s interesting. At the outset of 2012, there’s a question of who’s the underdog. And you might think Peter Thiel, being very wealthy, is the big guy. You might think Hulk Hogan is the big guy. But Peter was outed and had no recourse. So is he really more powerful than Gawker? Is Hulk Hogan, a world famous celebrity, more powerful than Gawker?

The litigation cost between 10- and 20-million dollars. Hogan could not have afforded to litigate the case that he won. And so it’s interesting, if we take the verdict that the jury gave as being justice. This is a case Hogan won that he could not have afforded to litigate.

SE: And Gawker knows this and that’s why the editorial strategy seems [in retrospect] completely unjust. To run a company doing things you know are unjust and illegal, refusing to take stuff down that’s illegal because you’re invulnerable and the little guy can’t afford to sue you.

RH: I also think people don’t understand what Gawker‘s role was in the media system. Often Gawker would break a story, like the Hogan story. And then the New York Times could report on it. They could publish unseemly information that the rest of the media could then report and follow up on. Gawker is not the only side that understands it’s basically suicide to sue a media outlet in this country. And look, for the most part that’s a good thing. You wouldn’t want powerful people to be able to intimidate the media into not covering them.

But at the same time, it means that if you’re an average person and you are unfairly or unjustly or illegally treated by a media outlet, you have very little in the way of recourse. I mean not just that it cost 10-million dollars to litigate the case. It also took almost five years, and it arguably made the sex tape much more well-known. And so an embarrassing situation is even more embarrassing for the plaintiff. And then unconscionable things that Hulk Hogan had done came to light as a result of the lawsuit.

It’s a bad system where people who might be guilty of unrelated things, who might have skeletons in the closet or be on financially unsound footing, are incapable of getting justice when it comes to media coverage about them.

SE: Gawker could have just written about it. They didn’t have to have it playing on their site.

RH: That’s a very important distinction that again has been lost in the media coverage. Writing about the tape is completely covered by the First Amendment. Playing an illegally and surreptitiously recorded sex tape of two consenting adults in the privacy of a bedroom, not as much. This is where copyright comes in, where privacy comes in. Where a number of other non-First Amendment related issues come in. And so Gawker knows they’re doing something illegal.

SE: They’ve been asked to stop doing it and they refused and left the sex tape up for over a year.

RH: The second cease and desist letter comes from Hogan’s lawyer and it’s an email to Nick and he says, “I appeal to you as a human being, please take this down. It was recorded without my client’s consent.” And they ignore this and in fact they also ignore a judge’s order to remove the tape and basically write an article that says, “Fuck you, you don’t get to tell us what to do.” That backfired in a major way, not just with the jury but that judge is the one who ultimately ends up presiding over the case. Gawker was so arrogant, and so unlikable as a defendant, that they made an already difficult case even more difficult to win.

SE: Peter Thiel’s destruction of Gawker is kind of the ultimate modern conspiracy. It seems from reading the book that you think conspiracies can be a good thing.

RH: If you look at my earlier definition, a conspiracy is a coordinated secret action designed to disrupt the status quo. So on the one hand, Peter “conspired,” I think, pretty objectively by any definition, to destroy this company.

Now is there also a conspiracy going on to destroy Alex Jones? It seems unlikely the Sandy Hook parents are funding these lawsuits themselves and that Alex Jones would mysteriously and suddenly be kicked off all these media outlets. The difference is people think of those instances of deplatforming as a good thing. I’m not making a judgement, but many people who see Thiel’s takedown of Gawker as bad also see the deplatforming of Alex Jones as good.

What I’m talking about in Conspiracy is a toolkit. Conspiracies are a way of accomplishing something that we should be more aware of because they do happen. There are conspiracies to assassinate people, or to steal things. In 1919, there was a conspiracy to fix the World Series. That’s not a good thing. However, there might be some billionaire funding the Stormy Daniels case, or the case against Alex Jones. There are good conspiracies and bad conspiracies. What I tried to do in the book is not say why this happened or that it was good or bad, but rather how it happened. Because it is incredible that this guy was able to, in secret, destroy a media outlet through one of the most covered stories and lawsuits of our time. And we should learn from that.

SE: He worked on this in secret for 10 years, while also making billions of dollars, funding hugely successful companies.

RH: He kept the plan secret and told the people involved only what they needed to know.

SE: The secrecy of it is almost superhuman. I’ve never even cheated on anyone. I would never get away with it; I’d rat myself out. So working in secret for 10 years, I can’t imagine getting away with that.

RH: Look, I’m sort of center-right politically, but when you look at the left what I mostly see is people who are so sure they’re right that their policies will obviously be embraced by the world and be automatically successful. And that’s not the case. If Thiel had said, “I’m going to destroy Gawker,” they would have realized much earlier the Hulk Hogan case was being bankrolled by someone else and changed their legal strategy.

SE: The strategy wouldn’t have been to outlast him.

RH: I think it was Napoleon who said: Never do what your enemy would like you to do for the reason that he would like you to do it. The whole idea that Gawker thinks Thiel should have been upfront about his intentions is exactly why, strategically, it would have been stupid.

You can say that a billionaire destroying a media outlet is the opposite of what the First Amendment is supposed to be about, and still be impressed that he did this incredible thing. Like, you can say that the Israelis should not be involved in covert kidnappings and assassinations yet still admire the efficiency or strategic brilliance with which they sometimes are able to do it. And again, the idea that because you don’t like something or you think that the outcome is bad doesn’t mean you should close your mind to it and simply condemn rather than understand it.

SE: It’s like in the Revolutionary War. If we fought the British the way the British wanted us to fight it, we would have lost.

RH: You need to understand these things. Like, calling someone Machiavellian is one of the worst insults. People don’t realize what Machiavelli’s book was actually was. Machiavelli was arrested and tortured for conspiring against the Medici. So then he turns around and writes The Prince, which he dedicates to the Medici. People think The Prince is about how to be a ruthless prince. In actuality, tyranny was anathema to what Machiavelli actually stood for. He’s writing about how power works, how power is seized, how it is defended, and what the mindset and approach of these sort of individuals is. The subtext of Machiavelli is how we defend ourselves against all this.

One of the stories told in Conspiracy is the story of how Eisenhower takes down McCarthy, who was obviously an individual with a massive platform that he was using for evil. He was pretending to care about communism but really he was just a demagogue trying to get power for himself. People don’t realize Eisenhower’s role precisely because Eisenhower never took credit for it and did it privately. But McCarthy’s demise was meticulously orchestrated by Eisenhower. Eisenhower said in a meeting, “This man will never become president as long as I’m alive. I will destroy this person.” But he knew that what McCarthy thrived on was outward conflict, so he said, OK. I can’t attack this person head on, so how can I slowly limit his power? How can I send proxies against him? How can I set him up to overreach?

SE: It’s interesting though that in the end maybe Peter Thiel wasn’t so successful. He destroyed Gawker but ended up hurting himself when it became known that he funded the lawsuit. This ends up having a destructive impact on his life. Kind of a “be careful what you wish for” sort of story.

RH: The day the verdict came down there was this New York Times piece where they interview three First Amendment experts, including the former general counsel of the New York Times. They all say that no precedent was set in this case except that you can’t run celebrity sex tapes. Basically, it was a very limited case and Gawker probably deserved to lose it. A lot of people in the media actually sort of cheered Gawker‘s downfall.

Only a month and a half later, when Thiel’s involvement is revealed, that suddenly changes. And I would argue Gawker has created a very successful sort of lost-cause mythology after the fact. You know Gawker was very early, supposedly, on the Bill Cosby case and the Louis CK case and a few others, so they’re looked at in a more heroic way. But it’s interesting that people didn’t take those articles seriously at the time because people tended not to take Gawker articles seriously. It didn’t have a great reputation for truth or stringent editorial standards.

Thiel’s involvement immediately shifted the narrative from Hulk Hogan as the underdog to Hulk Hogan as the bully and Thiel as the ultimate bully. The irony is that he went after this media outlet because he wanted privacy and now he has almost no privacy.

SE: That’s an interesting element of conspiracies, right? What happens when they’re successful.

RH: The unintended consequences of conspiracies cannot be overstated. The senators who helped to assassinate Julius Caesar in order to restore the Republic ended up obliterating any chance of that happening. Ceasar could have restored the Republic, and perhaps he intended to do it at some point, but his assassination set in motion a civil war and then Octavian becomes basically the dictator and emperor for life and it ends the Republic permanently.

SE: It happens over and over again: Conspirators turn against one another. The enemy of your enemy, it turns out, is not your friend. I’m thinking of the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks in Russia, the Marxists and the Islamists in Iran.

RH: Yes. You could almost argue that every single CIA conspiracy ever has ended up having blowback worse than whatever the problem was they were trying to avoid. In Afghanistan, we supported the Mujahideen and ended up creating al-Qaeda. Today’s freedom fighters are tomorrow’s terrorists. The person you assassinate sets in motion a different tyrant.

Clearly Peter Thiel’s main failing in this conspiracy, aside from any moral consideration, was his lack of planning for what happens after the win. That is the problem with most conspiracies: planned up until plunging the knife into Caesar, with no plan for what comes next. It’s a major strategic error.

How many people say, “I want to be a best selling author. I want to win a Grammy.” We think when we get what we want we’ll be happy and the world will magically be the way that we want it to be.

You could argue that the real [unintended] outcome of Thiel’s conspiracy was the election of Donald Trump. A lot of the tactics that he learned here, a lot of the media disdain that’s been kicked up and put in motion was then used for the election of a way bigger bully than Gawker ever was.