economics

What We Talk About When We Talk About Immigration

Focusing on immigration policy through the lens of political allegiance is both dangerous and often ahistorical.

My father moved to the UK from Iran in the 1970s to study engineering when he met and married my mother, who is from a small town in the Welsh valleys. Many people from that town would not have met a non-white person before they met my father. After the Islamic Revolution in 1979, my parents made the eminently sensible decision that they would build their life together in Wales and not Iran.

To this day my father remains the hardest working person I know. He always worked two jobs, became a successful engineer and I recall watching him take part in publicity photos in the 1990s as the first non-white retained fireman in Wales, which he went on to do for 25 years.

He is by any measure a credit to his community and can easily be held up as a model for “integration.” However, he is just one person. I sometimes wonder how different things might have been if there had been even one or two other Iranian families living on our street.

My father was born more than 3,700 miles from where I was born. By the age of three I’d already lived in four different countries. I grew up in a small town in Wales. By the time I was 15, I couldn’t wait to move to London. I’m writing this column in a hotel room in Japan. When it is finished I’ll send it to my editor in Australia and by the time you read it I’ll likely be back home in London. As an internationally minded academic, I have what Talcott Parsons called an “achieved identity” based on education and career success.

In truth, the interiors of hotel rooms, conference halls, or restaurants are largely interchangeable. The changes of location become little more than changes of backdrop and scenery because ideas do not know borders. David Goodhart distinguished between “somewhere people” and “anywhere people,” and by any measure I am an “anywhere person.” Spun positively this means I am “a citizen of the world,” or more negatively “a citizen of nowhere.”

Here I am looking at the same screen as people thousands of miles from me, and the people closest to me are never more than an instant message away. As Roger Scruton puts it, “Networks connect people by disconnecting them from space … Networked people may view with indifference the fact that they live in no particular place, or a place that belongs to anonymous others at the far end of the world.” And the networked people who inhabit these “anywhere” spaces – regardless of where they come from originally – are likely to be somewhat like me.

Much like an airport, the university campus is also an “anywhere” space, where you will meet people from all around the world who are somewhat like you. For those cocooned in their relative safety, and whose experience of people from different cultures and backgrounds has only ever come in such safe spaces, suggestions that some people might not want to live with other people who come from elsewhere seem xenophobic, small-minded, and racist. But how representative of most people and places are these anywhere spaces? Can the elite “anywhere people” begin to understand why the “somewhere people” stayed at home, let alone why they now don’t want the streets in which they grew up inhabited by people who don’t share their culture or language?

Last year Douglas Murray wrote a well-researched and erudite book called The Strange Death of Europe, which seemed to sum up what a lot of people were thinking, but the anywhere-person newspaper The Guardian’s only response was to call it “gentrified xenophobia.” We recently saw a cruder version of this same debate in the USA, when Jim Acosta asked Donald Trump why he called the migrant caravan an “invasion” which in turn led Trump to call him a “rude, terrible person.” The clashes between these two perspectives have too often created animosity and deadlock rather than honest dialogue. It has been difficult to discuss the issue of immigration sensibly, which I’m going to try to do here.

First, let’s be serious here: virtually no one when they are talking about their concerns about immigration in the current climate are talking about people who are skilled and highly educated like my father. This has been one of the more disingenuous moves made by those seeking to make an economic case for immigration: highlighting a specific top tier as the norm that can be applied to all.

Many of those who leave their countries of origin and do well already come from elite classes. For example, Brahmin from India’s highest caste represent only 3% of people in India, but 45% of Indians living in the United States (Source: Reihan Salam, Melting Pot or Civil War?, p. 40).

Meanwhile, India’s most disadvantaged groups, which account for more than a third of the total population account for only 1.5% of Indians living in the United States. Can it really be a surprise that the median household income of Indian Americans ($122,034, the highest of any ethnic group) is more than double that of white Americans ($57,617)? This is selection at work, and it would be dishonest to present these immigrants as being in any way typical of immigration as a whole.

Plainly, the immigration crisis in Europe and in America concerns poor and low-skilled immigrants, many of whom are either illegal (have not completed necessary paperwork and procedures) or refugees seeking political asylum. In the United States, there are estimated to be around 12 million illegal immigrants, which is around 4% of the population. The UK currently sees up to 70,000 illegal immigrants enter the country every year.

Focusing on immigration policy through the lens of political allegiance is both dangerous and often ahistorical. As a classical liberal, or libertarian, I am not generally disposed to supporting government controls including restrictions or “protections” on trade, which includes people as well as goods and services. In fact, historically, it has been the political left, and especially trade unions who have pushed for these things. In the 1970s, after a period of immigration restrictions in the United States during the post-war consensus, it was Milton Friedman who argued for immigration against a protectionist left.

If you go back and watch Friedman’s pioneering PBS Telecast Free to Choose, his opponents are most often trade union bosses. Here in the UK, Tony Benn and other voices of the hard left opposed joining the European Union. The trade unions traditionally supported strong immigration controls fearing the downward pressure that increased competition for low-skilled jobs might have on wages. They recognised and openly articulated that the special interests of the working class were diametrically opposed to those of poor immigrants coming from abroad.

For Friedman, uncontrolled immigration was only desirable in the free market and is fundamentally incompatible with the welfare state. The issue is that welfare is “sticky,” it takes away the incentives for people to move out. This is not only true of immigrants who fail to achieve their dreams (in the past many thousands of unsuccessful US immigrants moved back to their homelands), but also of native populations. Probably the banner example is the valleys of Wales where my mother grew up: once thriving coal-mining towns have now been destitute for almost forty years.

After the 1970s, there were migratory outflows from former coal-mining towns in the valleys of Wales, and likewise many moved from the Rust Belt that propelled Donald Trump to the White House. But in both places welfarism kept a core of people from moving away – providing just enough to block the natural migration that might have taken place, and equally just enough to curb innovation and new industries from taking the place of the old ones which in many of those places died in the 1970s.

In the past, before the welfare state, areas recovering from creative destruction were able to bounce back much more quickly. But since the welfare state has become so strong, the natural incentives to adapt to change are no longer there, which in turn can lock in endemic multigenerational poverty.

Some might point out that both the US and the UK currently have historic low unemployment numbers: both at 4 percent. But these numbers obscure the labour force participation rate, which is currently 62.9 percent in the US and 78.8 percent in the UK. In other words, 37.1 percent of working-age adults in the United States are not in work, while 21.2 percent of British working-age adults are not in work.

While not all of these people will be receiving welfare benefits, surely a good number of them will be. Also, many of those who receive benefits are in work. In the US, the total number of people on welfare is estimated to be around 59.1 million including children. In UK, 57 percent of family units receive some type of state support.

Now add immigration to the mix. Many of the people who move to Europe and America take the lowest paying jobs and live in unimaginable poverty. There are few genuine opportunities for upwards mobility for most of these people: how can they realistically compete with the native educated middle-class professionals for whom they perform menial labour?

The situation is perhaps most marked in California, which has an increasingly hollowed out economy with these low-skilled immigrants at the bottom, a small clutch of elites working for Silicon Valley firms at the top and very few people in between. In that state—sold to the rest of the world as a progressive utopia—28 percent of black people live below the poverty line, and one third of native Latinos, for those who entered the country illegally that number rises to two thirds. Household median income for Latinos in California is $47,500 compared with $69,606 for non-Latinos. The benefit of cheap labour does not come without its costs, as Reihan Salam notes:

It is generally accepted that it is more expensive to provide the same quality of education to disadvantaged kids than to those from better off families. For one, high-poverty schools often have a hard time attracting and retaining the best teachers, and poor children are more likely to need social services. Among immigrant families, only 70 percent of children live with someone who has a high school diploma or better. It is less likely that the children in immigrant families who don’t will complete college. Meanwhile, only 8 percent of fourth graders [i.e. children of 9-10 years old] in immigrant families are proficient in reading. Only 5 percent of eighth graders [i.e. children of 13-14 years old] are proficient in math. (Melting Pot or Civil War?, p. 35)

When you replace market mechanisms with central command and control planning, every decision becomes a zero-sum game. And in this case, every penny spent on a child living in poverty born to immigrant parents is a penny not spent on a child in a similar position born to native parents. This produces strong incentives for political struggle since the levers of power categorically allocate resources to this group or that group. Polarization becomes inevitable.

Welfarism also forces us to think in the utilitarian terms of net benefits and costs. In the US, the average immigrant with less than a high-school diploma will cost the taxpayer $115,000 over seventy-five years while the average descendent of an immigrant will cost $70,000. It is estimated that only 71 percent of foreign-born US citizens have high school diplomas. To put this in perspective, the tax payer cost over seventy-five years would be approximately $1.5 trillion. Here in the UK, the estimated cost of immigration from outside the European Economic Area over a decade is estimated at £118 billion.

In 2017, the Office of National Statistics reported that 50.5 percent of all households received more in benefits (including in kind benefits such as education) than they paid in taxes. Given these facts, there is a serious question: can we afford mass low-skilled immigration? Since there is a net cost in terms of taxation, what are the real benefits? Who benefits? It is those in the reasonably well-off middle classes who can afford cleaners for their homes, help to look after their children, and so on—increasingly common luxuries unimaginable to most people even a decade ago. As ever, the benefits are concentrated while the costs are dispersed and socialised. Make no mistake: you are subsidizing cheap home help for the most well off.

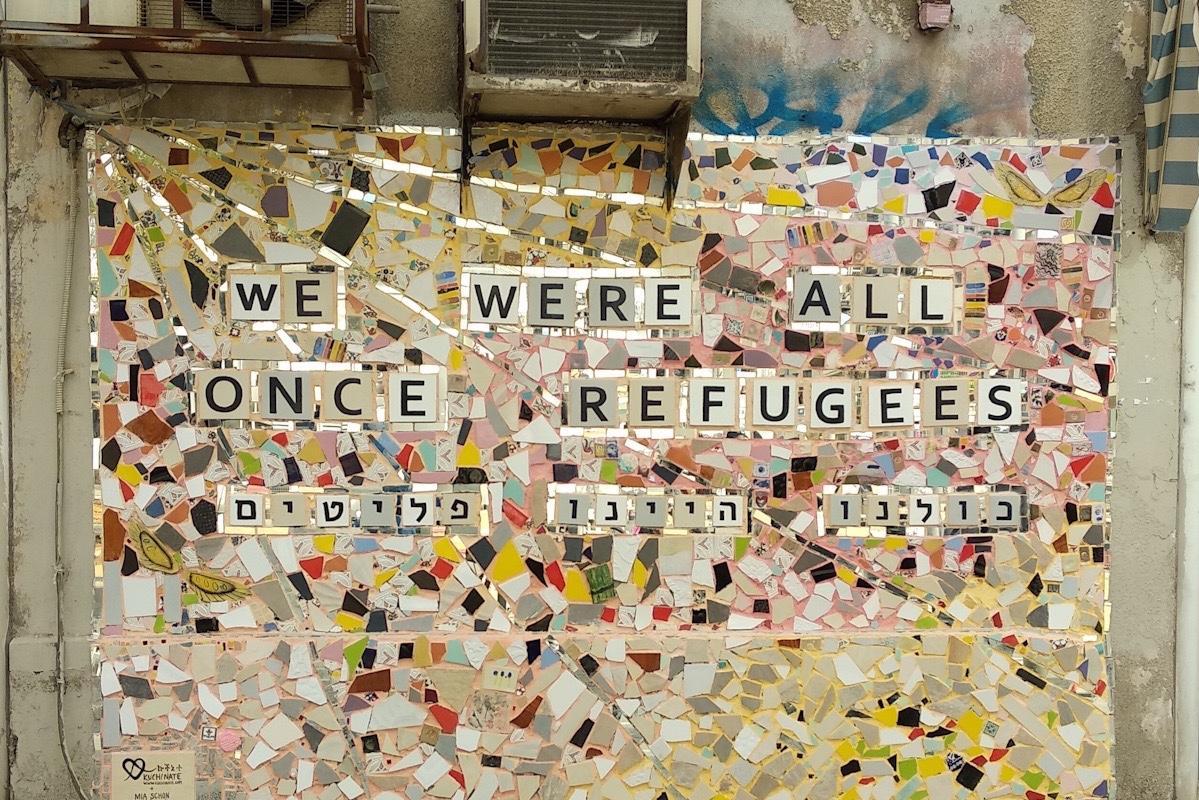

Immigrants then pay with their dignity, not only by living away from their home countries but doing so while entering the bottom rungs of western societies, doing the worst jobs. Meanwhile, the costs for natives is not simply higher taxes: it is school places, it is seeing the character of the childhood homes irrevocably changed not simply in terms of the ethnic mix, but in terms of culture, religion, and language. It is in many cases the cost of giving up that childhood home for pastures new—a choice for which they are often condemned by those lookers on who have not had to pay such costs themselves.

The English town of Smethwick is an instructive case. In 1964, it was the home of what has since been dubbed “the most racist election in British history,” which even saw a visit from Malcom X. Fifty years later, Smethwick would be unrecognisable to those who once lived there. According to the 2011 Census, 27.1 percent of the population were born outside the UK, and 20.5 percent predominantly speak languages other than English. Only 43.4 percent of the population list their religion as Christian; 17.9 percent are Sikh, 13.8 percent are Muslim while 2.2 percent are Hindu.

In 2016, Smethwick voted overwhelmingly for Brexit, which I am admittedly using here as a proxy for opposition to immigration (one of many principal reasons people cited for voting Leave). When analysing voting data, champions of mass immigration are often quick to point out that more diverse areas tend to vote in a more pro-migration direction: but they never seem to think about tracing the people who moved out of such areas, where they moved to, and how those people tend to vote. For example, the vast majority of white residents from East London, an area that became “majority minority” some time ago moved to Essex, which, like Smethwick, overwhelmingly voted for Brexit. In fact, it is estimated that over 600,000 white British people have moved out of London since 2001.

The same effects can be seen in the USA. Despite California’s image as the nation’s most progressive state, most ethnic groups in California have retreated into silos—while the virtue signalling progressives often tout their “inclusivity” from within their mostly-white gated communities, set apart from ethnic populations in non-gated but still ethnically segregated areas. In 2017, activists protested in the Latino enclave of Boyle Heights in LA against “hipsters.” They did not want the area to become gentrified and lose its Latino character—think about that for a moment.

As Democrat Michael Shellinger put it earlier this year “California is our most racist state.” But Shellinger doesn’t arrive at this conclusion with the typical kneejerk stance, as most progressives would expect when calling out racism. Instead he identifies the problem from looking at the facts rather than progressive dogma. He states, “California’s tragic poverty and widening inequality aren’t the result of racist policies imposed from without but rather progressive policies embraced from within.”