Education

Warning: Telling a Lame Joke in an Elevator can Endanger Your Career

It is nothing short of bizarre that an organization whose members study international conflict and know the value of dialogue over coercion opted for coercion from the outset.

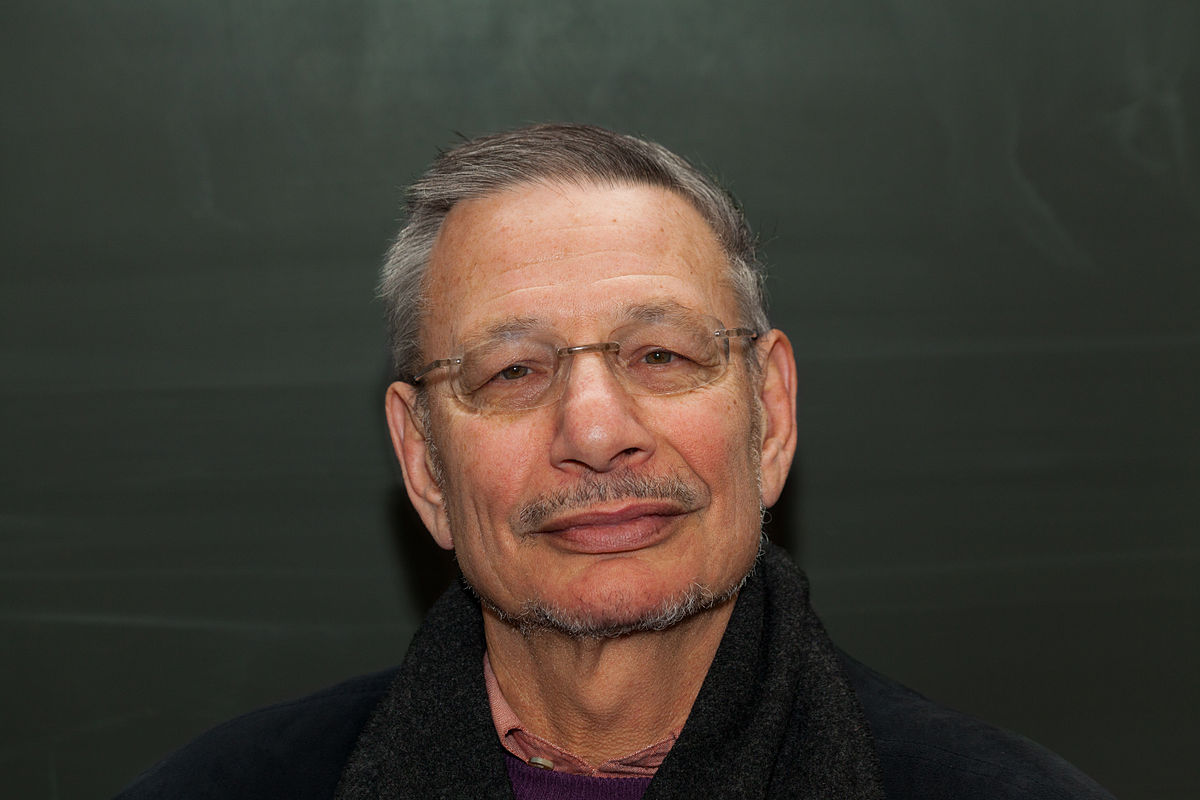

I am a professor of international political theory at King’s College London and bye-fellow of Pembroke College, Cambridge. I am a fellow of the British Academy and a member of the International Studies Association (ISA). Several years back the ISA voted me the “distinguished scholar of the year.” This year it censured me, not once but twice. I was guilty of saying “ladies lingerie” in a lift, and more disturbingly in their eyes, of writing a conciliatory email to the woman who had overheard me in the lift and filed a complaint. I appealed against this decision, but earlier this month was told my appeal had been rejected.

During the second week of April 2018, the ISA had its annual meeting in San Francisco. It attracts many thousands of members from multiple disciplines who do research on international relations. The meeting consists mostly of panels at which scholarly papers are presented and discussed. I stayed in the San Francisco Hilton, the venue of the meeting. On the third afternoon, I was going up to my room in a very crowded lift when a male voice asked people to shout out their floors so he could press the relevant buttons. People named floors and I said: “Ladies Lingerie.” I confess it is an old, lame joke; my youngest son later remarked that it was not the worst joke I have ever made. Upon reflection, I think these words came to mind because I was flush up against the back wall of the lift and feeling slightly claustrophobic. It was a way of releasing tension—or so I thought.

Two days later I learned that a member of the ISA had filed a complaint against me and that the organization would send it to its ethics committee for adjudication. I wrote a conciliatory email to the colleague who filed the complaint: Prof. Simona Sharoni, who teaches Gender and Women’s Studies at a small New England college. As she did not grow up in the U.S., I explained the intended meaning of what I said, apologized if it caused her discomfort and suggested we engage in a dialogue. I further suggested that to raise a complaint that many might consider “frivolous” would only provide ammunition to those who opposed the women’s movement and efforts by women to flag and seek redress for real forms of harassment:

Like you, I am strongly opposed to the exploitation, coercion or humiliation of women. As such evils continue, it seems to me to make sense to direct our attention to real offenses, not those that are imagined or marginal. By making a complaint to ISA that I consider frivolous—and I expect, will be judged this way by the ethics committee—you may be directing time and effort away from the real offenses that trouble us both.

I was wrong about the ISA’s response. The ethics and executive committees found me guilty of using a phrase they described as “inappropriate and offensive.” They censured me again for emailing Prof. Sharoni. They insisted that I offer an apology that would satisfy both them and her. I categorically refused. In acting this way, the ISA ignored its own code of conduct, which requires any aggrieved party to try to resolve a conflict privately before asking for adjudication from the ethics committee. Prof. Sharoni did no such thing and rebuffed my attempt to do so. She complained about my email and asked the ISA to tell me never to contact her again. It is nothing short of bizarre that an organization whose members study international conflict and know the value of dialogue over coercion opted for coercion from the outset.

I feel particularly aggrieved by my censure because in a career of 53 years of university teaching I have taught women, mentored women, and coauthored with women, and repeatedly argued that the only qualification for promotion in universities should be academic performance. I have received countless emails from colleagues since this incident, many from women in the field, expressing their support. They and other ISA members have written to the Association complaining about the decision and procedures. I am hopeful that this outcry from members will lead to my censure being discussed at next year’s business meeting as well as the procedures that allowed it to happen.

My censure quickly went viral. Ruth Marcus at the Washington Post heard about it and wrote a story. It was reprinted elsewhere, as was a version that was put out by the Associated Press. The Atlantic followed, with a story that excoriated the ISA for inappropriate and poorly constructed rules. In the U.K., the story was covered first by the Daily Mail, then by The Times, the Spectator, and various other outlets. I was interviewed on radio and television. I received endless emails and letters, all but two expressing total support. The other two were friendly and urged me “as a gentleman” to say I was sorry and let the matter pass.

The ISA leadership and Prof. Sharoni were furious about this publicity. She complained of receiving hate mail. I certainly do not condone trolls, but what did Sharoni and ISA expect to happen when they acted as they did? They created the kind of incident that would bring them both considerable negative publicity. Much of the criticism—quite properly in my view—focused on the negative implications of their behavior for freedom of speech, humor, and just common good sense.

The story did not end there. I filed an appeal on May 13—after finding out that May 15 was the deadline to do so. Mark Boyer, the Executive Director of the ISA, never informed me of the date, which I only learnt about from comments he gave to various newspapers. The ISA kicked my appeal into the long grass, as the British say, and would never have acted on it if my barrister had not sent them a letter threatening to go to court if we did not hear one way or the other. His letter elicited a response from them earlier this month denying my appeal.

Primary documents are always better than secondary ones, which are subject to quotation out of context to support particular interpretations. Accordingly, I attach my appeal below.

RICHARD NED LEBOW: APPEAL

On the advice of my legal advisor I file this appeal from the two judgments made against me by your organization. I confess that I did not submit a detailed rebuttal of the allegations when they were first filed because I found it hard to believe that any one could take them seriously. I only asked that my email exchanges with Mark Boyer be forwarded to the ethics committee.

My appeal consists of four parts: a review of the facts, interpretations of my remark in the elevator, iteration of what I believe are your procedural errors, and a statement about why this censure is so inappropriate given my lifelong support for women in the profession. It is based on both parts of Section 4 b of the Code of Conduct in force at the time the complaint was lodged. I hope that this appeal will be resolved with the same speed as the original censure.

Facts:

Prof. Sharoni did not ask people to call out their floors. It was a man’s voice I heard. She alleges I had “a smile on my face” but if she was standing in the front of the elevator as she says, she could not have seen my face all the way in the rear. I said; “ladies lingerie,” not “women’s lingerie,” because I was referencing the long-standing joke line. She says all of “my buddies” responded with laughter. I knew nobody in the elevator, and how would she know if I did? I don’t recall how many people laughed, but at most it was a few. What evidence do we have that there was another woman in the elevator and that she commiserated with her afterwards? Has this other woman complained or been identified by Prof. Sharoni?

Prof. Sharoni now alleges in media interviews that I “instigated” some of the overwhelmingly negative media coverage of her. How would she possibly know what prompted the media to cover the controversy? In point of fact, I initiated no media contacts. The Atlantic, which is doing a story, told me that they had been tipped off by a senior female academic. Ruth Marcus of the Washington Post, not surprisingly, refused to explain how she got wind of ISA’s action. Once the AP ran the story it went viral.

I am indeed sorry that Prof. Sharoni has received email threats; I certainly do not condone this kind of behavior. However, this attention is the product of an action that she began, not anything that I did.

Interpretations:

“Ladies lingerie,” as by now you all must know, is a joke dating back to the days of manually operated elevators. It is still frequently referenced today, as it is, for example, in the “Mythbusters” TV series and Harry Potter books. Surely, books that appeal to children, not only adults, would be careful to avoid any phrase or joke that might be considered offensive.

Why did I make the remark—admittedly not the best quip I have made? I am slightly claustrophobic and was relieving tension when jammed into the back of a very crowded elevator. I had no intention of offending anyone and had no idea I had until I received the complaint forwarded to me by Mark Boyer.

Many remarks have relatively transparent meanings. Cases in point are perhaps use of the “N” word, reference to women as “dumb bitches,” or obvious slurs of handicapped persons. My remark, by contrast, is open to many interpretations, most of them benign. Who knows, I might have been a transvestite out to shop for myself. There is nothing inherently offensive in “ladies lingerie” in my view, nor in that of the hundreds of men and women, members and non-members alike, who have since sent me supportive emails.

Who interprets what is offensive? If any party has the right to do so and demand an apology, we no longer have freedom of speech. And if a woman can take offense at the public utterance of “ladies lingerie” and have the ISA judge it as “inappropriate and offensive,” there is no limit to what words or phrases people out to advance their agendas will use. Perhaps ISA will receive a complaint by some person outraged and hurt by overhearing someone saying “evolution” in an elevator?

If an issue arises because of a remark the sensible thing is for the offended party and speaker to have an exchange of views. I tried to do this but Prof. Sharoni was only further offended.

Here too there is an issue for you to reconsider. Your ethics committee chastised me more for writing to her than for my remark. This is because once again you allowed her to impose her interpretation on the meaning and effect of my email. Why does she have the right to say she is offended by what she labels my misogynist remark, but I have no right to call her complaint frivolous? Are women treated differently from men by your ethics committee? I was clear that frivolous expressed my interpretation and I solicited hers in the hope of a dialogue that would resolve the matter.

Procedure:

There are several issues that trouble me here.

I queried Mark Boyer at the outset why he had not just rejected the complaint and was informed that the bye-laws gave him no leeway (see attached email chain). He was required to forward it to the ethics committee. Your code of conduct states that the matter should be resolved informally “if practicable” (Code of Conduct Addressing Grievances, Section 1). Mark, in fact, did have a choice, which he inexplicably did not exercise.

There was no reason why some informal meeting, even mediation, between Prof. Sharoni and me could not have been set up. I would have been more than willing to participate. The elevator event took place early in the meeting and presumably we were both in town afterwards. If not, it would have been easy to set up a video conference.

As students of international relations, we know that dialogue is the first step in addressing conflict and coercion the last. Your executive director passed up the opportunity for dialogue; rather, he, the ethics and executive committees went directly for coercion. This makes no sense substantively. It is also in violation of the ISA’s declared policy (see above) that conflicts first be addressed by informal means. The Code of Conduct throughout clearly places great emphasis on informal dispute resolution methods.

Mark’s initial email to me also insisted that I treat the complaint confidentially. I emailed him asking what grounds he had to make such a demand. He replied that he had none (see attached email chain). I emailed prof. Sharoni hoping to establish a dialogue with her. She had no interest in dialogue, and, as you know, lodged a second complaint with Mark.

Mark mentioned nothing to me in his emails about a right to appeal. I only found out about this by reading his comments to reporters that now appear in newspapers. He told them that I had until 15 May to submit an appeal. I have since checked the Code of Conduct, where it says that an appeal must be lodged “within a reasonable period of time” (Section 4 c). Here too, his behavior remains inexplicable.

I would like to know if the ethics and executive committees actually met to discuss the complaint, how many members were present, and if those who were not were consulted.

My Reputation:

There are many men who are “serial offenders.” It is easy to give credence to new allegations of harassment or worse when complaints have repeatedly been made about them in the past. I have never been the subject of any professional complaint for any reason from a woman—or anyone else for that matter. This is the first time this has happened to me and I continue to maintain that the complaint in question is “frivolous” in nature.

Quite the reverse is the case. I have been a supporter of teaching, hiring, and promoting women throughout the course of fifty-two years of university teaching. I have coauthored with women and regularly mentor and help junior women colleagues find publishers, grants, and jobs, and write supportive tenure letters. I know you have received emails from women who have testified to my support of women, and have asked Mark Boyer to forward them to you. I have received many more emails of this kind and append a few to this document.

Finally, there is the matter of the apology demanded by the ethics committee. I already offered what I think is an appropriate apology in my email to Prof Sharoni. I informed her that “I certainly had no desire to insult women or to make you feel uncomfortable.” I refuse to extend the kind of apology ISA wants me to make as it would acknowledge that there is something wrong about saying “ladies lingerie” in an elevator or writing an email to the offended party explaining my intent and offering my judgment about the consequences of her behavior for efforts by women—and men—to combat misogyny.

ISA’S REPLY

The ISA’s lawyer wrote a largely indecipherable letter in not very good legalese and also, I presume, the letter signed by the organization’s president, Patrick James. The letters are dated 13 November and 15 October 2018 respectively. The ISA took almost six months to respond to my appeal and its president sat with the lawyer’s letter for a month before passing it on. Rather than reproduce them in full, I offer the following extracts from the President’s letter.

The International Studies Association (“ISA”) Executive Committee (“ExComm”). . . found the following pertinent facts:

1) Someone on the elevator asked others what floor they wanted.

2) You replied either “Ladies’ Lingerie” or “Women’s Lingerie.”

3) Prof. Sharoni filed a Formal Complaint pursuant to the ISA Code of Conduct against you based on your statement…

4) The ExComm forwarded the complaint to the Executive Director for initial review. The Executive Director determined that the complaint fell under the ISA Code of Conduct. See id. You were then informed that the complaint had been filed against you…

5) The ISA President initiated an investigation of the complaint…

6) You were given the opportunity to explain your side of the story to the PRR and to bring forth any other relevant evidence. . . . Despite being given this opportunity, you declined…

7) You chose to contact Prof. Sharoni directly. Although you explained that your comment was intended as a joking reference to an old, cultural trope, your email was not apologetic and PRR (and eventually ExComm) found that it was marginalizing and trivializing Prof. Sharoni’s reaction to your comment and that it was an attempt to intimidate her from following through with her complaint.

8) The PRR (i.e. the investigating committee) . . . . recommended to ExComm that the matter should be resolved by (i) requiring you to provide an unequivocal apology to Prof. Sharoni…

9) ExComm reviewed the evidence and determined that your conduct violated the ISA Code of Conduct. ExComm communicated the resolution of the matter to you, i.e. if you apologized, no further censure would be imposed…

What follows in the letter is a recapitulation of my allegations of procedural regularities on its part, which it disputes on the grounds that the word “should” in the Code of Conduct does not mean “must”—that is, it’s advisory, rather than mandatory.

In sum, we note that “should” does not mean “must” and thus neither informal resolution nor mediation are required under the Code.

Finally, we reviewed your claim that the ExComm’s decision is manifestly unreasonable. Based on the facts and the evidence discussed herein, it was not manifestly unreasonable for ExComm to determine that a violation of the ISA Code of Conduct occurred.

This is the first mention of my being in breach of the ISA code, and it is unclear just what article I violated. But then, I suppose they are acting on the premise that offense is the best defense. My appeal argues that they violated the ISA code in repeated ways. Rather than defending their actions, they have charged me with the same misdemeanor. It is unusual, to put it mildly, for a letter rejecting an appeal to include a brand new charge, even more serious than the one being appealed against.

The letter goes on to address the substance of my remarks:

One crucial point to note is that ExComm actually took the explanation contained at the start of your email to Prof. Sharoni as sincere and at face value. Some members of the committee (primarily the older members) knew to what you were referring even before your explanation. We believe you intended this only as a reference to an old trope. That said, one has to consider how someone who, because of age or culture is unfamiliar with that trope, would have interpreted your comment. Without that anchor, it is difficult to imagine that your comment could have been interpreted in an inoffensive way. Thus, a violation of the Code of Conduct did occur.

Thus, the resolution from ExComm, requiring that you unequivocally apologize is not manifestly unreasonable. Lastly, the ExComm also decided that if you decline to issue an apology that ExComm will issue you a formal, private letter of reprimand on behalf of ISA.

In sum, ExComm finds that your appeal is without merit and will be forwarding this response and the documentation to the Governing Council for a final determination.

Readers will note that the ISA considers its bylaws for governing disputes merely as guidelines. I do not think I would get very far making this argument to a police officer who stopped me for speeding. The ISA President further indicates that the meaning of any remark is to be decided only by the person who claims to be offended by it. There is surely no faster way of shutting down freedom of speech and humor than by enforcing a rule such as this one.

Research and teaching require freedom to think and say what one wants. So too does democracy. Students need to be exposed to ideas with which they disagree or make them feel uncomfortable. That said, there are reasonable—but self-imposed—limits to discourse in society. Indeed, there are certain words and phrases that provoke discomfort, even anger, and responsible people need to be careful about using them. Certain words and phrases are considered beyond the pale, and for good reason. But the decision not to use them is a matter of personal choice and self-censorship, if it occurs, is the result of the judgment of civil society after considerable debate, not the imposition of censorship by fiat by organizations or government. One can only hope that “elevator gate,” as many have come to call it, encourages the kind of open thoughtful discussion that all controversies deserve.