Top Stories

The Novel Isn’t Dead—Please Stop Writing Eulogies

I refuse to be discouraged by the sort of novel-gone-to-the-dogs pessimism that has been around for generations.

The 69th National Book Awards Ceremony will take place this Wednesday in New York City. Nominees for the Fiction award include Brandon Hobson’s novel Where the Dead Sit Talking, Rebecca Makkai’s The Great Believers and Sigrid Nunez’s The Friend—all excellent and acclaimed specimens of a literary genre that English novelist J. B. Priestley had called a “decaying literary form” even before Nelson Algren’s The Man With the Golden Arm won the inaugural National Book Award for Fiction back in 1950.

Two decades later, postmodernist American author John Barth argued in The Literature of Exhaustion that the novel may have “by this hour of the world just about shot its bolt.” He won a National Book Award six years later for Chimera. More recently, Zadie Smith discussed her “novel nausea” while paraphrasing David Shields’ description of the crafted novel, “with its neat design and completist attitude,” as being “dull and generic.” Her most recent novel, Swing Time, made last year’s National Book Award longlist.

None of these obituarists seem to agree on the novel’s hour of death. According to veteran The New York Times writer Doreen Carvajal, the novel died in the 1980s, when books started to be valued less on their literary content and more on their sales. And yet over at The Guardian, Robert McCrum claimed a few years ago that the 1980s ushered in a golden age for writers and publishers alike. Meanwhile, Will Self, author of 11 books and five collections of short stories, claims the novel has been in a state of decay since the beginning of the 20th century, and is “absolutely doomed to become a marginal cultural form, along with easel painting and the classical symphony.”

While it is hard to argue with grand, subjective generalizations about the state of the novel, some objective facts are known: It is true that many novelists find it harder to make a living today compared to just a decade ago. A study done by the Authors Guild in the United States found that from 2009 to 2015, the average reported income of full-time authors decreased by 30%. Self-described part-time authors had their income decrease by 38% over the same period. However, this trend doesn’t seem to be affecting the best-selling literary novelists. Colson Whitehead sold 825,000 copies of The Underground Railroad. Emma Healey sold 360,000 copies of Elizabeth is Missing. Kate Atkinson sold 187,000 copies of A God in Ruins. These are strong numbers for literary fiction.

It is the “midlist” writer—the novelist who dedicates years of her life to writing a book that will sell perhaps 15,000 copies from Amazon and the deep recesses of Barnes & Noble—who is seeing her income disappear. Midlist writers frequently are having their manuscripts either rejected outright or accepted with a small advance. Rupert Thomson, a midlist author of over 10 novels, reports that an editor at Faber & Faber told him that he’d love to publish Thomson’s new work, but can no longer afford to offer respectable compensation. When Thomson asked what the editor could offer, he was presented with an amount so tiny that, by the author’s report, “I went home and sat at the kitchen table and drew up a balance-sheet. I thought: I’m going to have to change the way I live.”

Broadly speaking, there are two reasons commonly cited for the decline in sales and income. The first is what author Douglas Preston calls “the censorship of the marketplace”: Since midlist writers are no longer given advances large enough to survive on, many great books are simply never written in the first place because would-be authors are too busy working full-time jobs. As Preston argues, serious novelists need “time, space and quietude.”

The second commonly offered reason for the decline of the novel is—as author Chuck Palahniuk argued on the Joe Rogan Podcast—that people don’t want to read difficult fiction anymore because film, television, and even high-end video games and podcasts serve that appetite better. People want to be comforted by their books. They want to turn pages in the safe knowledge that the cop will catch the criminal. By this reasoning, one expects authors such as James Patterson—who markets himself as the world’s “most trusted storyteller”—to continue making their millions without creating anything of enduring literary value, while the novel itself becomes a byword for schlock.

I will admit that Patterson’s dominance doesn’t do much to arouse optimism. (His just-published novel, Girls of Paper and Fire, is summarized this way on his web site: “Each year, eight beautiful girls are chosen as Paper Girls to serve the king. It’s the highest honor they could hope for…and the most demeaning. This year, there’s a ninth. And instead of paper, she’s made of fire.”) But I refuse to be discouraged by the sort of novel-gone-to-the-dogs pessimism that has been around for generations.

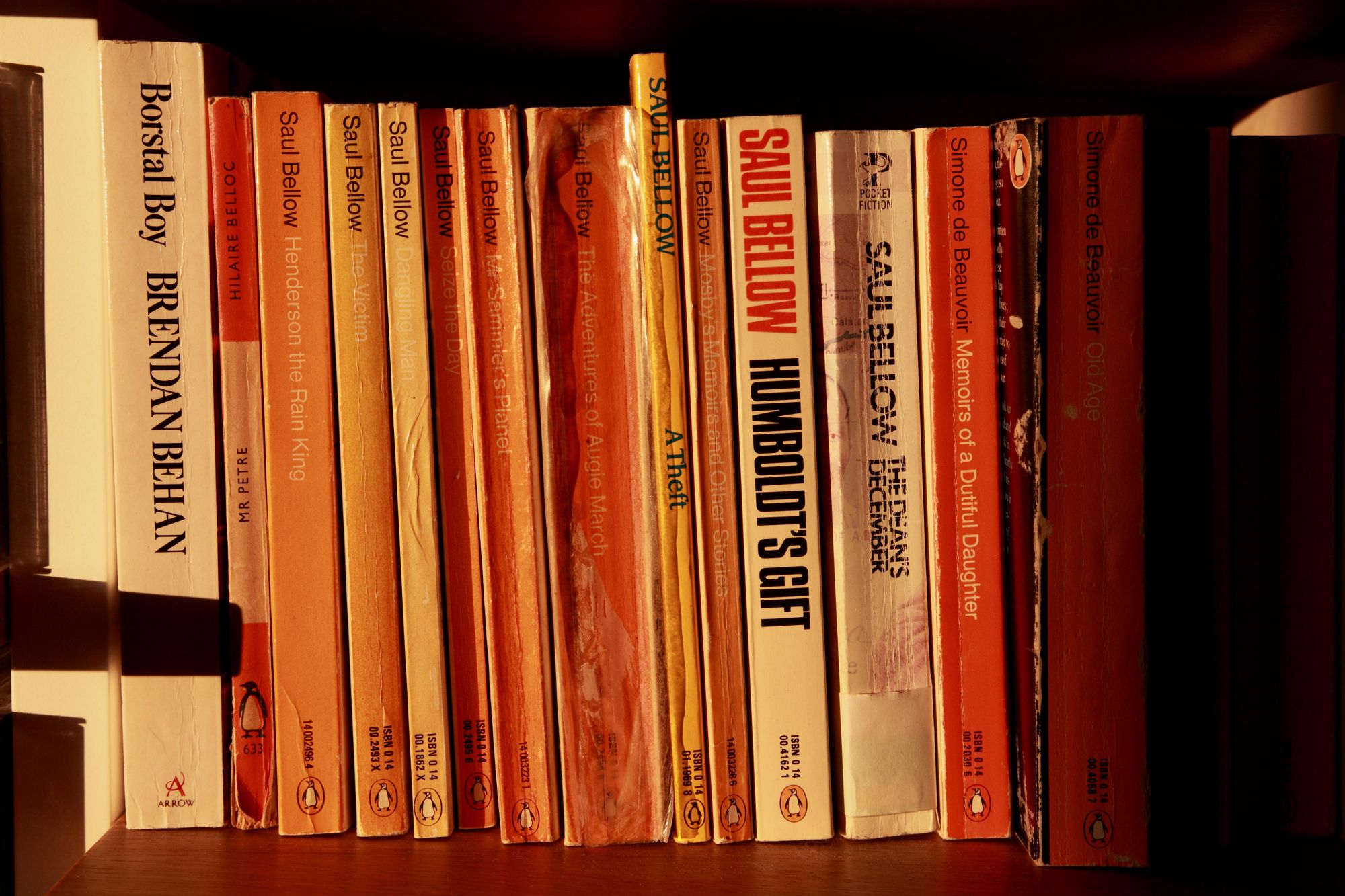

The fact is, the plight of midlist writers is not a new phenomenon. It took Henry David Thoreau five years to sell 2,000 copies of Walden. Saul Bellow, one of the great American novelists of the 20th century, was 45 before his novels earned him a comfortable living. His first two novels were commercial failures and it wasn’t until his sixth, Herzog, that he made the bestseller list.

If it were true that novelists needed “quietude, time and space” to produce novels, Preston would be right to declare a state of crisis. But Bellow wrote his first novel while serving on a merchant marine ship during the Second World War. He wrote his second while teaching at the University of Minnesota. Admittedly, he had some “quietude, time and space” after he was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship in 1948, which gave him the opportunity to move to Paris and write his third novel. But he soon returned to America and joined the University of Chicago as a faculty member. He held that position while he wrote Herzog (a National Book Award Winner), Humboldt’s Gift (National Book Award) and Mr Sammler’s Planet (Pulitzer Prize).

And if Palahniuk were correct about the lack of interest in difficult fiction, one would expect to see a wide chasm between the books that win literary awards and the books that are bestsellers. However, Lauren Groff, who has twice been nominated for the National Book Award (including this year), has made the New York Times bestseller list three times. And two of the books that made this year’s longlist, Tommy Orange’s There There and Tayari Jones’ An American Marriage, were bestsellers. Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, the aforementioned novel that sold more than 800,000 copies, also won the National Book Award.

Groff’s most recent book, Florida, is a National Book Award-nominated collection of short stories tied together by geographical location and psychological condition. There are alligators, hurricanes, and stray dogs that attack. After the narrator of The Midnight Zone concusses herself by falling off a stool, her kids tell her stories while she struggles to stay conscious. In Dogs Go Wolf, two sisters are abandoned at a cabin in the middle of nowhere. The pair slowly starve while wondering if anyone will find them. In Above and Below, a woman, after losing her university funding and getting dumped by her boyfriend, is forced to live in her station wagon. These are not exactly soothing bedtime stories.

The author’s previously nominated book, Fates and Furies, examined a marital relationship from first the husband’s and then the wife’s point of view. Midway through the novel, Groff vividly describes the wife’s formative years, beginning with the violent death of a sibling and the abandonment by her parents, followed by years of being cared for by a prostitute grandmother, who makes her sleep in the closet, and then by a shady uncle who works as “some kind of manager in a bad organization.” Again, not an easy or comforting book to read. Yet it spent six weeks on the bestseller list.

That said, it is true that the novel has been under siege from other forms of entertainment. As poet Philip Larkin noted in 1984, shortly before his death, movies and television signaled the end of the written word as the primary form of entertainment amongst the educated class. Well into the 20th century, he noted, a “plethora of dailies, weeklies, monthlies and quarterlies” had to publish writing of all kinds just to keep up with reader demand. But when televisions became a common household item during the Cold War, the public appetite for conventional written works went into a gradual decline. The result is that every generation of publishers generally has had to be more careful with their money, since they could no longer afford to take as many chances on books that might not generate a profit—a category that often is coterminous with books that won’t get picked up by TV or film producers.

Authors of a certain age are wont to complain that publishing houses now are run as a business first and a creative endeavor second. But companies can afford to indulge high-flown artistic missions only when they are insulated from competitive market forces. Publishers once could cast their bets widely (some would say lazily) on a legion of longshot wannabes, knowing that the few blockbusters that emerged would generate enough money to cover the duds. Sometimes, that took the form of editors staying loyal to their writer friends who had lost their market (or never had one to begin with).

Now, however, publishers use modern market-tracking tools to filter out the duds and hangers-on upfront, while investing their acquisition money with the handful of writers who can deliver a big hit. In 2017 alone, Whitney Scharer, Kate Hope Day and Kristen Roupenian all signed million-dollar-plus book deals. Indeed, anecdotal evidence suggests that the number of seven-figure advances has actually increased in recent years—even as five-figure mid-list deals have waned. It’s the same ruthless segregation of winners from losers that you see in many industries.

But this doesn’t mean you have to be a superstar to get published—because the same big publishers that have been tightening their purse strings are also losing their power as gatekeepers. Anyone can publish stories on Medium, a platform that has a monthly readership of 60-million people. Crowdfunding services such as Patreon allow readers to donate to their favorite authors directly. And self-publishing gives authors the opportunity to earn more per sale than through high-overhead bricks-and-mortar publishers in New York or London. Kickstarter even allows novels to be crowdfunded before they’ve been written. When a big publishing house takes interest in a writer’s self-published work, that writer can point to her established audience and sales history as a means to leverage a large advance.

The publishing industry and its readers once were joined at the hip. They needed each other. But that is no longer the case. So yes, it’s true that the average midlist novelist can no longer fund a middle-class life with a steady succession of advances. But if she’s willing to act independently, and put her product directly to readers, she may find that monetizing true writing talent has never been easier.