Top Stories

A Mania for All Seasons: The Continuing Importance of 'The Devils of Loudun'

Huxley’s dissection of a seventeenth century social pandemonium, whipped up in an era of shifting sexual mores, is a timeless indictment of the latent monstrousness within all human beings.

There are many people for whom hate and rage pay a higher dividend of immediate satisfaction than love. Congenitally aggressive, they soon become adrenalin addicts, deliberately indulging their ugliest passions for the sake of the ‘kick’…Knowing that one self-assertion always ends by evoking other and hostile self-assertions, they sedulously cultivate their truculence…Adrenalin addiction is rationalized as Righteous Indignation and finally, like the prophet Jonah, they are convinced, unshakably, that they do well to be angry.

These words first appeared in 1952, in the pages of Aldous Huxley’s The Devils of Loudun. While many of Huxley’s works are better known and more widely read, there may be no text, past or present, more relevant to our turbulent era than this account of a seventeenth century witch trial.

Huxley composed this passage to shed light on the mind of a thoroughly unlikeable individual by the name and title of Father Urban Grandier, in particular. But he also offered it as a more general analysis of the mindset afflicting those who burned Grandier to death—with the approval of both the Catholic Church and the State of France—for being a sorcerer in 1634. In the context of the entire work, this passage was part of a close inspection of the susceptibility of humanity to moral panics, show-trials, and mob justice across the ages.

For, although The Devils of Loudun is a book about particular persons at a particular time in a particular place and the atrocities they committed, it is more obviously an inquiry into the reality of demons and their inception. And on these questions, Huxley is emphatic, even to the point of indicting himself—they come from inside each of us:

…looking back and up, from our vantage point on the descending road of modern history, we now see that all the evils of religion can flourish without any belief in the supernatural, that convinced materialists are ready to worship their own jerrybuilt creations as though they were the Absolute, and that self-styled humanists will persecute their adversaries with all the zeal of Inquisitors…Such behavior-patterns antedate and outlive the beliefs which, at any given moment, seem to motivate them…In order to justify their behavior, they turn their theories into dogmas, their bylaws into First Principles, their political bosses into Gods and all those who disagree with them into incarnate devils…And when the current beliefs come, in their turn, to look silly, a new set will be invented, so that the immemorial madness may continue to wear its customary mask of legality, idealism, and true religion.

Huxley’s dissection of a seventeenth century social pandemonium, whipped up in an era of shifting sexual mores, is a timeless indictment of the latent monstrousness within all human beings. And it carries a particular relevance for our fevered political moment, replete with monomaniacal intersectionalists, prosyletizers for utopian ethno-states, religious fanatics, Antifa vandals, paranoid anti-Semites, millenarian conspiracists, and virtually anyone else called upon by some Hegelian or Abrahamic doctrine to ceaselessly fusillade public discourse with slurs and bitter invective.

* * *

Assigned to the Diocese of Poitiers as the priest of Saint Croix in the town of Loudun, France in the 1630s, Father Urban Grandier was—by the standards of any age—an insufferable egomaniac and—by the standards of his own day (and, to an extent, our present time)—a sexual deviant and generally morally dissolute individual. Shortly after his arrival, Grandier abused his position of power and influence to flout his vows of celibacy and sleep with, and then discard, a series of widows. In addition, he impregnated a 16-year-old young woman (Phillipe Trincant) placed under his tutelage by his best friend in the town, the Public Prosecutor of Loudun. Discovering Phillipe was pregnant, Grandier dropped her without a qualm. Following the birth of Phillipe’s child, she and her family were practically ruined in the eyes of their fellow citizens.

Fueling these cruelties was an infinite capacity on the part of the priest for haughtiness, rumor, and slander that extended well beyond his sexual proclivities. Grandier repeatedly contravened, defied, and openly insulted persons of influence throughout society for the pettiest of reasons. The most notable of these was the man that would soon run France, Cardinal Richelieu—an arrogant act of carelessness that likely sealed Grandier’s fate at the stake years later. Huxley reports that Grandier entangled himself in quarrels in which swords were drawn against him as a result of his vicious remarks. On at least one occasion, he instigated a contest of the Dozens with the lieutenant criminel of Loudun, which escalated from slander and insult into a feud of such a pitch that the priest had to barricade himself inside the chapel of the city’s castle to escape an armed mob. In the few brief years since his arrival in the town, it would hardly be an exaggeration to say that Grandier had offended or wronged at least half of Loudun (and a third of the town was protestant, so they already disliked him as a point of sectarian principle), as well as a considerable portion of the Roman Catholic hierarchy in France.

Although there were repeated attempts to bring Grandier to justice for his transgressions and crimes—at least one of which involved a stay in prison—he always managed to escape punishment. An exceedingly clever and eloquent (if not a precisely moral or forward thinking) man, the priest always slipped justice, which saved him the trouble of learning anything that might help him mend his ways.

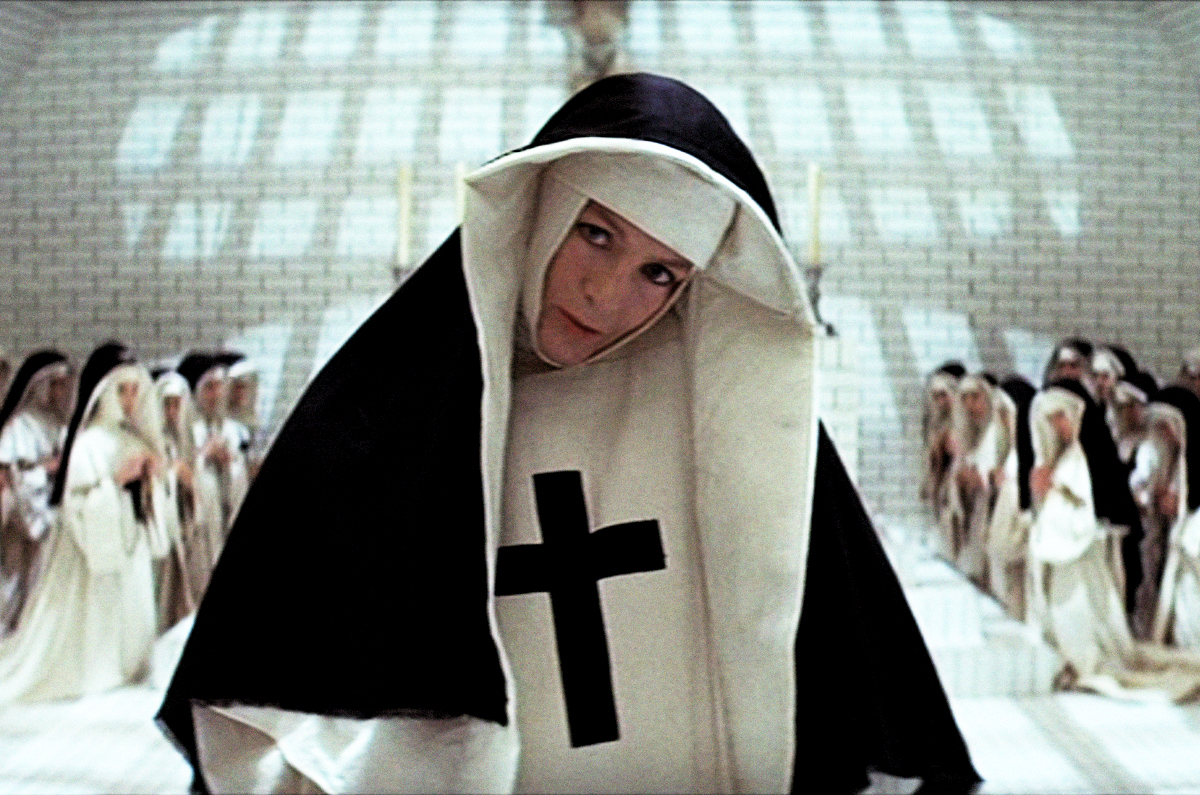

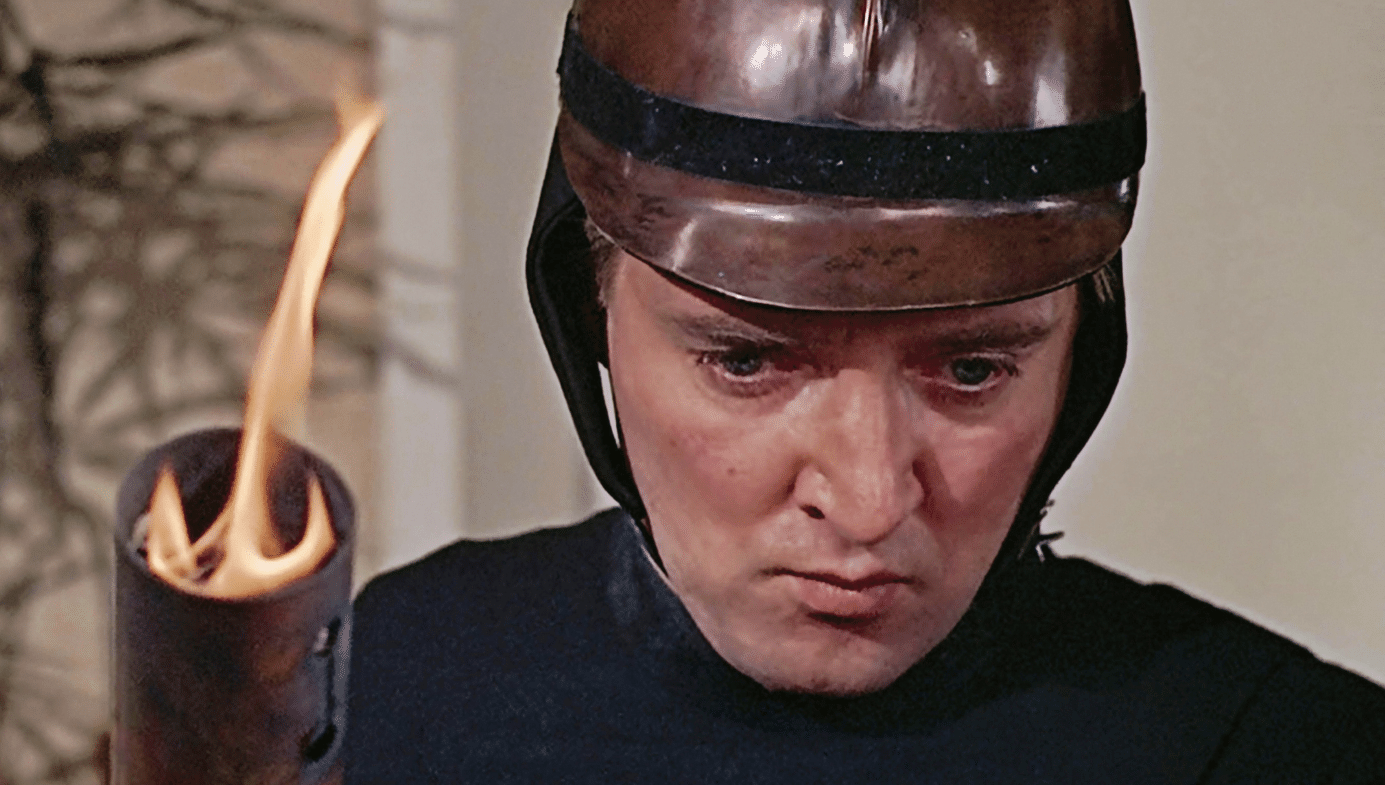

Then, in 1632, an infestation of demons at the Ursuline convent of Loudun— concentrated on the Sisters therein—was attributed to Grandier by the nuns and, subsequently, members of the Roman Catholic heirarchy. Spurred forward by their own hatred of Grandier, and supported by large portions of Loudun’s populace wronged and ruined by the priest, within two years of the nuns’ possession Grandier was tortured and burned to death for the crime of sorcery.

In the two years leading up to his execution, however, the town of Loudun was to be turned into a circus of the type that would be immediately recognizable to anyone familiar with today’s 24-hour news cycles. As sensational stories of blasphemies, supernatural phenomena, and horrifying public exorcisms raced across Europe, these events created a lucrative, continent-wide tourist industry in the town. In the midst of this grim side-show, it is also a matter of record (principally from the journals of clergy, citizens, and visitors from Britain and across Europe) that several of the nuns, townspeople, and priests bore false witness, later retracted those falsehoods, and altogether exploited these young women to fill the coffers of the town, the Church, and the pockets of a few enterprising individuals selling baubles and false relics while women were being tortured and humiliated before their eyes. Some of the nuns even attempted suicide to assuage the guilt they carried for their lies, until they were prevented by their ecclesiastical superiors and encouraged to redouble their fabrications.

* * *

Throughout The Devils of Loudun, Huxley frames the mayhem in the Christian terms with which those in seventeenth century Europe were equipped to understand it. To provide further insight, he applied the scientific findings and theories of the 1950s (some of which have since been discredited), and analyzed the psychology of the “possessed” and Grandier through the rather unscientific lens of Christian and Eastern mysticism. He also applied theories of parapsychology that most, in our present era, would categorize as outright quackery. It is through this combination of early seventeenth and mid-twentieth century intellectual paradigms that he dissects the anatomy of a state-approved murder, and the epidemic of lunacy which instigated it. Despite some of his unconventional methods, his observations are, on the whole, piercing:

At any given time and place certain thoughts are completely unthinkable. But this radical unthinkableness of certain thoughts is not paralleled by any radical unfeelableness of certain emotions, or any radical undoableness of actions inspired by such emotions. Anything can at all times be felt and acted upon, albeit sometimes with great difficulty and in the teeth of general disapproval. But though individuals can always feel and do whatever their temperament and constitution permit them to feel and do, they cannot think about the experiences except within the frame of reference which, at that particular time and place, has come to seem self-evident…in 1592 sexual behavior was evidently very similar to what it is today. The change has only been in thoughts about that behavior. In early modern times the thoughts of a Havelock Ellis or a Krafft-Ebing would have been unthinkable. But the emotions and actions described by these modern sexologists were just as feelable and doable in an intellectual context of hell-fire as they are in the secularist societies of our own time.

Focusing on the shifting sexual mores of the age—the move from Medieval to Renaissance sexual attitudes (what Huxley refers to as the ‘gray dawn of respectability’)—as well as the horrific backdrop of the 30 Years War and the paradigm-shattering onset of systematic scientific inquiry into virtually every corner of human life, Huxley argues that this tumultuous era generated not only technological and epistemological upheavals, but also a chaotic reconfiguration of sexual attitudes and practices.

Huxley frames Grandier as something of a cad in a cassock. He was a man who, in earlier times, would likely have never been called to account, let alone punished, for his indiscretions and abuses—an egomaniac without the perspicacity to notice he had strolled into a new era where the sanction of even the most powerful institution on earth wouldn’t be enough to save him from the unprecedented social upheavals then occurring. To the nuns, Huxley attributes a form of sexual obsession with (and, given that he could get away with that for which the Sisters would be utterly destroyed, potentially sexual resentment towards) Grandier. Either the nuns resented Grandier’s amoral promiscuity, or they wished that he would seduce them and were furious when he did not. When an exploitive narcissist like Grandier collided with the sexual frustration and panic of women delivered unwillingly into cloistered celibacy by families unable to pay medieval dowries, it was inevitable that something awful would happen.

It was not, however, inevitable (let alone just) that a man innocent of the ancient charge of sorcery in the service of Satan would be burned to death even after he confessed (under torture) to his previous, and very real, transgressions and practically begged to be killed for what he had done. Nor was it inevitable that a group of women, who were almost certainly mentally disturbed to one degree or another, would be manipulated by prominent persons in the town and various members of the Roman Catholic hierarchy in order to destroy a man who had previously given them so much trouble.

And yet, even though there were people who knew the truth of what was being done to Grandier—some of them powerful enough to prevent his horrible fate—that is precisely what happened.

* * *

In our present age, the ugly truths provided by Huxley seem prescient. To read this book is to understand that what the world (and the Western World, in particular) is currently experiencing is nothing new. With regard to the more wicked and wretched aspects of human psychology across the ages, the observations and arguments presented in The Devils of Loudun cut clear to the bone. Huxley’s analysis of human sexuality will be called sexist—and in certain instances, it is—and yet the case he makes for a sexual panic is convincing. Others will find his arguments about the human propensity for mob justice insulting on the grounds that we, unlike our forbearers, know better. But the priesthood and townspeople of Loudon almost certainly felt the same condescending superiority over those who preceded them, and so on, down the line into the relative fog of antiquity and the absolute fog of prehistory.

Neither of these criticisms, however, changes the predicament in which society presently finds itself. Sexual abuse; sexual panic; character assassination; the interminable search for evil in every corner of human interaction; the fear to disagree openly or to defend ideas we find noble and people we know are being treated unjustly; the rejection of logic in favor of presupposition; us-versus-them thinking as the source of personal and group identity; the specter of mob justice—all of these are, Huxley argues, abiding human attitudes and actions which produce such a frenzied assault on procedural and proportional justice that they undermine the very foundations of our shared society.

It is fitting, therefore, to allow Huxley the final word on our perennial mania—a diagnosis of our terrified moment:

The effects which follow too constant and intense a concentration upon evil are always disastrous. Those who crusade, not for God in themselves, but against the devil in others, never succeed in making the world better, but leave it either as it was, or sometimes even perceptibly worse than it was, before the crusade began. By thinking primarily of evil we tend, however excellent our intentions, to create occasions for evil to manifest itself …Today it is everywhere self-evident that we are on the side of Light, they on the side of Darkness. And being on the side of Darkness, they deserve to be punished and must be liquidated (since our divinity justifies everything) by the most fiendish means at our disposal…And on a very small stage, this precisely was what the exorcists were doing at Loudun. By idolatrously identifying God with the political interests of their sect, by concentrating their thoughts and their efforts on the powers of evil, they were doing their best to guarantee the triumph (local, fortunately, and temporary) of that Satan, against whom they were supposed to be fighting.

Aldous Huxley’s ‘The Devils of Loudun’ is available in paperback from Harper Perennial’s Modern Classics Collection.