identity politics

White Privilege Is Real, but Well-Meaning White Liberals Are Helping to Perpetuate It

Rather than whites being responsible for the perpetuation of these stereotypes—and, by extension, white privilege—they are maintained by all groups as they interact with each other.

After hosting African-American writer Ta-Nehisi Coates on his television show, Jon Stewart asked Coates whether America’s changing demographics could finally upend the anti-black society portrayed in Coates’s autobiographical Between the World and Me. Coates was doubtful, but Stewart, speaking for many white liberals, replied, “I hope you’re wrong.” Stewart’s presumption is that America’s ethnic transformation will relegate whites, and their prejudice, to the sidelines, ending racial inequality.

Regardless of whether Coates is correct to portray American society as tilted against African-Americans, his skeptical response was closer to reality than Stewart’s. The stereotypes, worldviews and institutional practices that advantage native-born whites over other groups—in America and Europe—arise as the result of a complex interaction between individuals and collective representations. Stereotypes about African-Americans are passed on from parents and peers, encoded in cultural products, and internalized by blacks themselves, who may come to cherish them and condemn other African-Americans for failing to “act black,” i.e. comply with those stereotypes. To imagine this thinking is limited to white people is naïve and belied by the research literature. In fact, stereotypes about African–Americans are easily acquired by Asians, Latinos and even African immigrants. Meanwhile, stereotypes about Hispanics and Muslims may be adopted by African-Americans. What distinguishes whites is not that they are uniquely susceptible to embracing stereotypes about other races and ethnicities. It’s that stereotypes about whites are, for the most part, positive rather than negative.

At one time, whites were more susceptible to this thinking because stereotypes about blacks or indigenous peoples helped justify slavery, settlement and colonialism. But that argument is difficult to sustain today. With 1960s social reforms and broad-based attitude changes, the link between white group consciousness and anti-black discrimination is tenuous. Some whites remain prejudiced, but they no longer shape the norms and narratives of the media, government and corporations in their group’s interests. None of which means white privilege has fully disappeared. Indeed, field experiments show that while discrimination has declined, those with distinctively black or Muslim names suffer a penalty in the labor and housing markets. Yet these experiments do not show that whites discriminate against blacks and Muslims more than other racial groups do.

Rather than whites being responsible for the perpetuation of these stereotypes—and, by extension, white privilege—they are maintained by all groups as they interact with each other. If, as the evidence shows, black policemen shoot black suspects at similar or higher rates than white policemen; if Asian or Hispanic recruiters are as likely as whites to discriminate against African-Americans; if those of all races push white candidates toward leadership roles in unions, progressive organizations or left-wing parties; then white people alone cannot be blamed for white privilege. It’s inception, perhaps, but not its continuing existence.

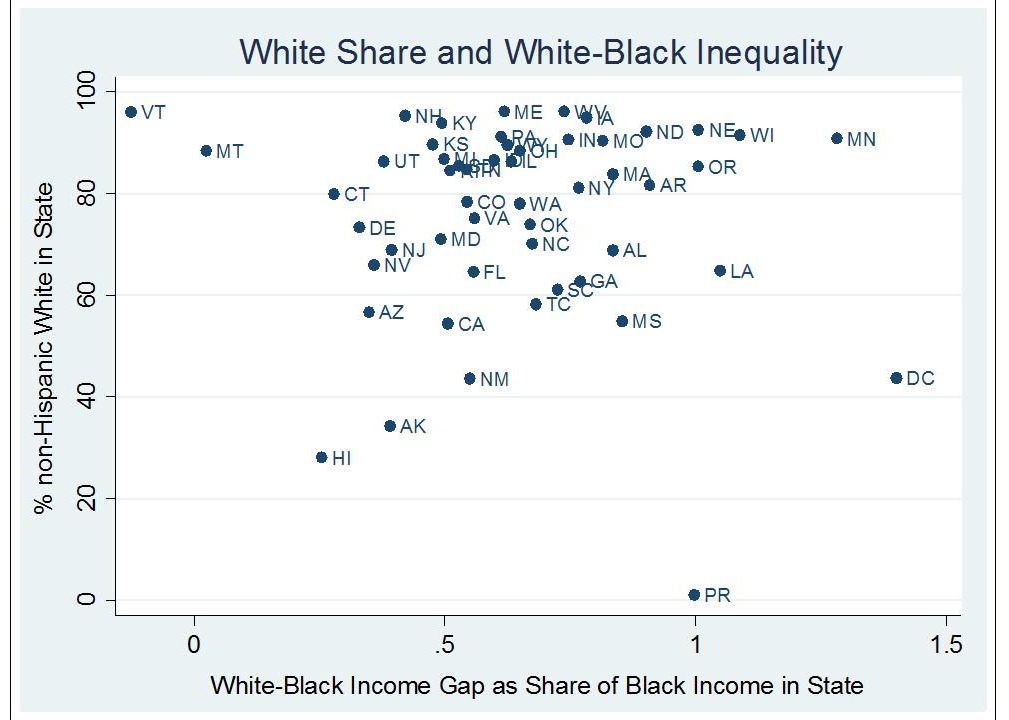

If actual whites were using their influence to enhance white privilege, we would expect the wage gap between blacks and whites in a region to get progressively higher in direct proportion to the percentage of white people in that region. Yet as figure 1 shows, there is no state-level relationship between white population share and white privilege. Whites earn far more than blacks in largely white Minnesota, but earn just as more in diverse Washington, D.C. and Louisiana. African-Americans are relatively equal to whites in homogeneous Vermont, but also do quite well in largely non-white Hawaii.

Figure 1.

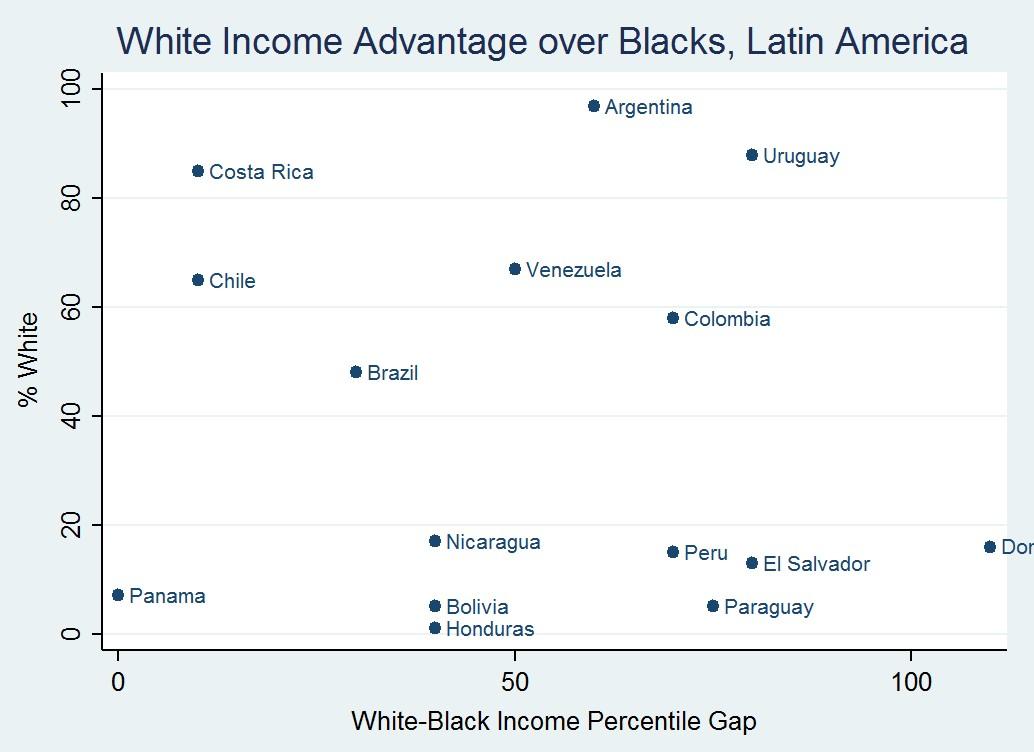

Okay, so there is no direct relationship between population share and black-white income inequality at the level of U.S. states. What about countries? As figure 2 shows, the same pattern applies—or, rather, absence of a pattern. The income gap is high in majority-white Uruguay, as you’d expect if whites are responsible for maintaining white privilege. But it’s also high in Latin American nations where whites are scarce, such as the Dominican Republic. Income equality, by contrast, is high in both Costa Rica, which is mostly white, and Panama, where whites form a small fraction of the total. The same pattern holds for British Local Authority districts and American ZIP codes. All of which suggests a conscious effort on the part of white people, utilizing their social and economic power, is not the main cause of their continuing advantages.

Figure 2.

But if white privilege stems from a system in which inequality emerges from complex interactions between groups, which is what the research suggests, why do people on the Left insist on attaching a white male face to it? The answer lies in evolution, which produces human brains that respond best to vivid mental images. Religions anthropomorphise complex natural phenomena like thunder and lightning, whose laws are deaf to human longings, into a morality play involving benevolent gods and evil demons. Scott Atran and Ara Norenzayan argue that religions produce incongruous images like men in the sky to open up a direct line to our emotions. So too with progressive ideology. A system that disadvantages blacks, immigrants, Hispanics or Muslims comes to be imagined as a machine operated by an omnipotent white god.

Why is this a problem? When student activists, radical professors and human resources departments assign blame to flesh-and-blood white men this becomes a meme which circulates in the right-wing media, stoking white resentment. The perception among white populations is that society discriminates against whites—that they’re being unfairly blamed for other people’s problems—and that becomes tinder for the populist fire. In polls conducted after the 2017 Charlottesville riots, 70 percent of white Trump voters agreed that “white people are currently under attack in this country.” Fifty-five percent of White Americans say whites are discriminated against. In the 2016 American National Election Study (ANES), the share of white Trump voters expressing this opinion is three times higher than among white Clinton voters. After party identification and views on immigration, this is the strongest predictor of a Trump vote. The instrumental role white grievance played in securing Trump’s victory is the theme of recent work by University of Pennsylvania political scientist Diana Mutz.

Some whites believe that their group is responsible for a system which disadvantages minorities, but they are overwhelmingly Democrats. The 2016 ANES pilot survey shows that only around 10% of pro-Trump whites feel some guilt for being white compared to 50% of anti-Trump whites.

Because whites are (wrongly) believed to be responsible for perpetuating white privilege, liberal gatekeepers are constantly on the look out for evidence of “racism” whenever someone expresses a pro-white sentiment. Other ethnicities and races are permitted to promote the interests of their group, but not whites. Even moderate expressions of white communal identity are discouraged, associated with the sins of the past and de-legitimized as beyond the pale. Duke University political scientist Ashley Jardina shows that the share of white Americans who identify with their race roughly doubled between the 1990s and 2010s—into the 45-65% range—as the country became more diverse. Importantly, those with stronger white identities did not express more antipathy to minority groups than other white Americans. On the contrary, the reverse was true. Meanwhile, according to Zach Goldberg, a Ph.D. student in political science at Georgia State University, 2016 marked the first year on record that “white liberals rated ethnic and racial minorities more positive than they did other whites.”

As white group consciousness rises, the divide between whites who believe their group controls a system of white privilege and those who don’t is emerging as a political fault line. Liberals tend to believe in a kind of reverse white exceptionalism: that whites, in contrast to every other ethnic and racial group, should suppress their communal identity because it’s linked to a system of racial inequality. They seek to deconstruct white identity as an ideological construct designed to maintain power. Cultural conservatives, by contrast, consider whites a group like any other—attached to particular myths, symbols and memories—which should be able to express its identity and interests without fear of censure.

Nowhere is this fault line more stark than when it comes to attitudes towards immigration. This was laid bare by a question I fielded in a YouGov-Policy Exchange survey in the U.S. and Britain in February 2017 which asked whether whites who wished to reduce immigration to help maintain their group share were being racist or “racially self-interested, which is not racist.” Seventy-three percent of white Hillary voters think it is racist for a white person to want less immigration to help maintain group share compared to 11 percent of white Trump voters. By contrast, just 18 percent of white Hillary voters believe it’s racist for Latinos to want more Latin American immigrants to boost their group’s share of the population, compared to 39 percent of white Trump supporters.

This gap is considerably larger among American whites than among white British people, fewer of whom think expressions of white self-interest are racist. In follow-up surveys where people were asked to explain their reasoning, it became clear that white Hillary voters who supported Hispanic or Asian, but not white, group interests believe whites are different from other groups because they are motivated by a desire to maintain their political and economic advantage over other groups.

However, if these white liberals believe that suppressing expressions of white interest will erode white privilege, they’re mistaken. The system of privilege, to the extent that it still exists, is not contingent on the continuing support of white people, whether they’re allowed to express that support or not. Moreover, labelling policy preferences you disapprove of as “racist” increases support for these policies among some whites and chastising their supporters for being politically incorrect makes them more likely to vote for Trump, not less. The message that whites are conspiring with each other to maintain their unfair advantages is at odds with reality and alienates an important tranche of voters. This makes it difficult to build a voter coalition that might elect candidates willing to address the real causes of white privilege. Rather than imagining a world of conflicting groups in which whites oppress non-whites, we should think of white privilege as a complex structure which all people of all races and ethnicities bear some responsibility for. Instead of adopting a simple minded narrative which demonises white identity and casts white people as the villains, we should encourage the whole of society to work collaboratively to reduce system bias.