Top Stories

The Spectrum of Black Contrarianism

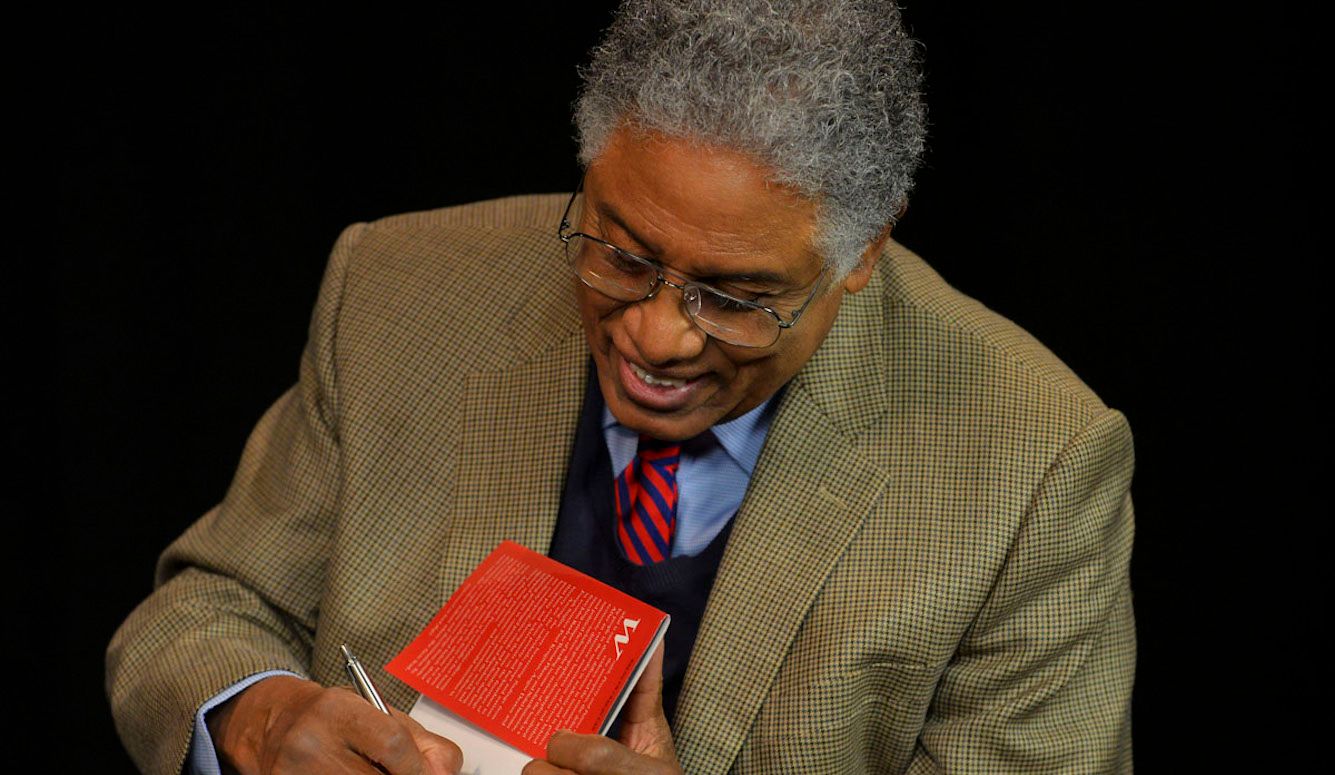

The likes of Thomas Sowell and Larry Elder reject not only the economic program of the Left but also the racial grievance politics of black activists and politicians.

African-American politics are, it is often supposed, monolithic. Since the late 1960s, following the signing of landmark civil rights legislation by a Democratic president, the Democrats support of The Great Society, the anti-Civil Rights Act campaign of a Republican presidential nominee in 1964, the adoption of the “Southern Strategy” by Republican operatives in the latter part of the decade, and the decline of the Northeastern liberal wing of the GOP, black voters have emerged as the most reliably partisan voting bloc in American politics. They are the cornerstone of the Democratic coalition. This near monopoly of African-American party affiliation however does serve to obscure broad and diverse fissures within the philosophical landscape of the black community. There is wide-ranging discontent with the status quo of African-American politics and relatively little passion for the establishment liberalism that guides it. The question is, could this diversity of opinion allow for the realignment of political forces within the black community? Or are these dispersed frustrations inalterably resistant to meaningful coalitional rearrangement?

On October 11 2018, rapper Kanye West visited Republican president Donald Trump in the Oval Office. He was joined by Jim Brown, an NFL legend who has been revered in and beyond the black community as an icon of the civil rights era. During that meeting, West launched into a series of abstract policy musings and philosophical flourishes (punctuated with some profanity, swipes at liberal critiques, and effusions for President Trump) that left many fans and observers upset and bewildered. That Kanye West, erstwhile arguably America’s most popular African-American artist, could wholeheartedly support a president whose politics and rhetoric seemed to fly in the face of the perceived interests and sensibilities of the black community has mystified many in the commentariat. Indeed, West may have reasons for supporting the president that are inscrutable.

But one plausible explanation for his support also serves to illustrate the basis upon which a broader axis of contrarian sentiment towards the institutional mainstream of black political culture persists. That is the simple fact that the trend of social and economic progress in the black community during the decades of this hegemony has been, relative to all other ethnic groups, scantly positive and, in certain keys areas, dramatically negative. One does not have to spend any great amount of time reminding people where the black community resides on the scales of topline social statistics. African-American men constitute roughly 35 percent of the prison population while representing 7 percent of the total population. They average a life expectancy roughly 5 years below the average of all other American males. African-Americans graduate high school at a mere 69 percent nationwide and do so at the lowest rate of all four major racial groups in America in all but 11 states (where they slightly exceed Latinos).

Then of course there is the obvious fact that African-Americans suffer higher rates of poverty than do any other major ethnic group. In fairness to the record of the Democratic Party in this area however, it should be noted that while poverty rates and unemployment remain starkly higher for blacks than for white and Asians in particular, actual material quality of life has risen dramatically since the 1960s. Alongside most of America’s poor in general (of whom blacks represent nearly 25 percent, as measured by SNAP receipts) malnourishment has been nearly eliminated. The vast majority of poor Americans (including African-Americans) have television, a home computer with internet access, cell phones, and cars. A decline in the price of consumer goods, as well as a dramatic increase in subsidized income (not counted when calculating poverty rates), has made this rise in living standards possible.

Yet this superficial layer of success does manage to highlight a broader failing of the broader Democratic program with respect to poverty and the black community in particular. It is a failing that illuminates the deep frustrations of black critics both in and outside of the Democratic Party and the progressive movement. The black middle class has expanded and poorer blacks have greater access to material goods. But a regressive institutional cycling of young black men through substandard educational systems, arguably biased criminal justice processes, and back out into a labor market for which they are no longer qualified, or in which (by virtue of criminal record) they are barred from achieving social mobility, has made this lifestyle of ameliorated poverty nearly as much a ceiling as it is a floor for millions of America’s black poor. It is not difficult to see how this pattern feeds the phenomenon of criminality and dependency that persists in so many of America’s urban centers.

“We say if people don’t have land, they settle for brands.” This was one of Kanye West’s more cogent remarks from the now infamous summit with the president. The remark is poignant: the importance of ownership and self-determination may have come to sound like conservative bromides to some. But for African-Americans across the spectrum—evidenced in part not just by the sermonizing of black conservatives but by the entrepreneurial mythologizing of Hip-Hop icons like Jay-Z, P Diddy, and West himself—there is a lament that a rampant and shortsighted materialism (for which Hip-Hop is also a vehicle) has displaced a focus on economic independence and a culture of self-sufficiency.

Enter Jim Brown. If Kanye West’s newfound political alliance with President Trump is confusing to many people, Jim Brown’s more restrained support is probably more so. Brown holds an exalted place in the rich history of civil rights activism that paved the way for the dramatic social and legal changes that we have largely come to take for granted in modern day America. This places Brown within the pantheon of America’s great left-wing social activists. But a look at Jim Brown’s history reveals a man firstly concerned with not just the social but the material plight of the African-American community beyond the partisan dueling of Democrats and Republicans. Brown was the founder of the The Negro Industrial and Economic Union(eventually renamed the Black Economic Union), launched largely with funds donated by the Ford Foundation with the goal of catalyzing entrepreneurial activity in the black community.

Almost three decades later, Brown would found the Amer-I-Can Program, an organization focused on maximizing the achievements of particularly black youth “by equipping them with the critical life management skills to confidently and successfully contribute to society…through self-determination.” Jim Brown has been a fierce racial critic of American social culture for all of the last 50 years. Yet, as we dig beneath mere social commentary, a deeper look at the substance of Brown’s work historically sheds light on the source of his sympathy with at least the sound of Donald Trump’s economic platform. An affinity for the working class political language of a Republican president, whose rhetoric echoes that of industrial class pro-labor Democrats of Brown’s generation, almost surely plays a role, not just in Brown’s support of Trump, but in his apparent disillusionment with the black political mainstream. It is in understanding Jim Brown’s discontent with black Democratic politics that a common thread of black criticism for this political establishment comes more clearly into view.

There are different categories of black resistance to be found in the Democratic mainstream of American politics in general, and on the elite rungs of black leadership within the Democratic Party in particular. The most obvious category would be the category of black conservatives who stand in opposition to the Democratic Party and modern liberal ideology in general. The likes of Thomas Sowell and Larry Elder reject not only the economic program of the Left but also the racial grievance politics of black activists and politicians such as Maxine Waters, Al Sharpton, and a younger generation of black activists who have articulated the black political mission as being against the hegemonic dominance of “white supremacy” and capitalism.

Sowell describes the roots and impact of such “victimhood culture” in this way:

People have a vested interest in black victimhood…without black victimhood you cannot get black turnout and the Democrats would lose a lot of elections…

…[there was] an order issued during the Obama administration that the schools must reduce the disparity in discipline of black males and that government money would be withheld if they didn’t. And one of the things that has happened is that you’ve seen an enormous escalation of violence…in order to keep their numbers right to please the federal government all kinds of things are ignored…

They are joined in this latter type of dissent by a small but important coterie of centrist and traditionally liberal black intellectuals including Glenn Loury, John McWhorter, (Quillette writer) Coleman Hughes, politically independent commentators like Tommy Sotomayor, black nationalists like Umar Johnson, and otherwise mainstream black liberal journalists such as Juan Williamswho once wrote:

Every American has reason to ask about the seeming absence of strong black leadership. Where is strong black leadership to speak hard truth to those looking for direction? Where are the black leaders who will make it plain and say it loud? Who will tell you that if you want to get a job you have to stay in school and spend more money on education than on disposable consumer goods? Where are the black leaders who are willing to stand tall and say that any black man who wants to be a success has to speak proper English? Isn’t that obvious?

There is, in other words, within the black community a center-Left to conservative Right constituency that rejects major elements of mainstream black political and social leadership on the grounds that, in its zeal to oppose conservative policies and expand government benefits, it has failed to create the prerequisite conditions for material opportunity. In addition to which, this generically liberal leadership has seemingly failed to set a cultural standard conducive to the character building of black youth and the stability of the black family.

These are the points of discontent advanced by the conservative and more traditionally liberal voices within the black community. Yet there are deep resentments of the prevailing political class to be found on the hard Left as well. This includes the voices of protest intellectuals like Angela Davis, Democratic-Socialists like Cornel West, and a younger generation of progressives and leftists including the likes of Ta-Nehisi Coates, Marc Lamont Hill, and many within the Black Lives Matter movement.

What does this left-wing contrarianism look like? Angela Davis and Cornel West have both been fiercely critical of the “neoliberal” democratic mainstream, the policies of which (as supported by the Clintons and the Congressional Black Caucus, and later by Barack Obama and Al Sharpton) have led to the mass incarceration of young black men (specifically in the 1990s), imperialistic military adventurism abroad, and a selling out of working class interests to “Wall Street Oligarchs” at home. Ta-Nahesi Coates, while critical of Senator Bernie Sanders’s lack of a specific focus on racial justice, nevertheless made a point of supporting him over Hillary Clinton in the 2016 Democratic primary. Marc Lamont Hill, who self-identifies as a leftist, declined to vote for Hillary Clinton in 2016 and, even more tellingly, declined to vote for Barack Obama in 2008. Hill then reflected that in the black faith tradition to which Obama held such appeal, hope had been a “belief that, in spite of all evidence to the contrary, our circumstances can be transformed into something previously unimaginable.” But, “In Obama’s corporate-sponsored universe of meaning, however, hope is not the predicate for radical social change, but an empty slogan that allows for a slick repackaging of the status quo.”

The left-wing black discontent expressed by the likes of Hill, Cornel West, and Coates seems fundamentally at odds with the substance of the liberal-centrist and conservative discontent found among thinkers like John McWhorter and Larry Elder. The former would pillory the likes of McWhorter and Hughes for defending the racial politics of what they call “white supremacy,” while the likes of Larry Elder would decry a Marc Lamont Hill or Cornel West for espousing ideas more radically socialist than anything ever offered by Barack Obama. Even in the case of a traditional liberal like Coleman Hughes and a libertarian like Larry Elder, whose views on race reality in America largely align, there is a sharp divergence in the area of policy that would seem difficult to bridge.

There is a cross-spectrum convergence, however, in the spirit of African-American discontent with the black political mainstream. It is evidenced in Elder’s amusement at Sowell’s claim that he would not try to convince Jesse Jackson to abandon his victim-oriented approach to politics because Jackson “would have to reduce his income by 90 percent.” Compare this to Cornel West’s disparaging of Al Sharpton for openly admitting he would never criticize President Obama because he is black, or Coates’s descriptionof Sharpton as “black America’s first virtual leader, a product of a collective longing for the romance of the 1960s and an inability to cope with the complexities of 21st century African Americans.” Whether we are referring to a leftist like Angela Davis, an industrial Democrat like Jim Brown, a conservative like Thomas Sowell, or an enigma like Kanye West, there is a universal sense among black critics of the black mainstream that these leaders, and the larger generically liberal Democratic Party structure which their influence upholds, are fundamentally unserious about solving the graver problems of black community.

Creating agreement amongst these contrarian thinkers around a positive agenda would be a daunting task. But if these are the parties that are willing to have a more serious conversation, it may be that they are the ones who should be talking. Only then can deeper agreements arise, as they occasionally did in African-American history between socialists like WEB Du Bois and conservatives like Booker T. Washington, or between liberals like Martin Luther King, Jr. and black nationalists like Malcolm X.

Unlikely? Perhaps. But necessary? Yes. Consensus over the need for criminal justice reform has grown across the divide over recent years. The need for local community empowerment and personal responsibility is—in theory, at least—a universal value. So too is the desire to oppose racism (however much of it there may be) and to achieve lasting victory in the historic struggles of black America. Stronger bridges of dialogue must therefore be built. In American politics, stranger things have happened.