Law

On the Fallibility of Memory and the Importance of Evidence

As individuals making personal judgments about the truthfulness of Kavanaugh and Ford, we are not held to the same standards as our justice system.

As we await the vote on Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation and the results of the ongoing FBI investigation, America is left to ruminate a little longer on the testimonies he and Christine Blasey Ford gave before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee. Both were highly emotional and heartfelt. Ford sounded like someone who had experienced a trauma, and Kavanaugh sounded like a man falsely accused. Both left you wanting to believe the person on the stand, even if neither’s story remained completely consistent. But who should we believe? Shall we “believe the victim” or assume that the accused is “innocent until proven guilty?” A closer look at the science and nature of human memory, the historical trends on the accuracy of eyewitness testimony, and the prevalence of wrongful convictions demonstrates that the most reasonable assumption is to believe both.

The Constructive Nature of Episodic Memory

Sometime in the early 1980s, Sigmund Freud’s theories of the subconscious and the psychosexual stages of childhood experienced a resurgence in popular culture. However, there was one important difference: his descriptions were no longer believed to be metaphorical, but real. According to researchers M.F. Mendez and I.A. Fras:

This paved the way for a decade of “uncovering” of memories, whose technique, particularly in children, was fraught with suggestion, and which culminated in bizarre and tragic phenomena such as the McMartin Preschool case of the late ’80s, in which innocent adults were falsely imprisoned on the basis of children’s suggested “memories” of often lurid and theatrical sexual abuse. In the wake of these events, investigators demonstrated that false or altered memories of events, even very traumatic ones, can be endorsed as “real” by otherwise normal people.

The science of “recovered memories” has since been mostly discredited, and according to the American Psychological Association, “Little or no empirical support for such a theory” has been found. But these events introduced the public to a concept that researchers had been quietly uncovering for years: memories are not concrete, nor do they simply deteriorate with age. They are malleable, changeable, and easily influenced by suggestion. These changes are incorporated into the original memory to a degree that they seem every bit as real as its truest aspects. As Yale researchers Marcia K. Johnson and Carol L. Raye noted, “All experience is constructed in that people use their general knowledge of the world to fill in ‘missing elements.’”

For this reason, memories are subject to what is known as the Misinformation Effect.

The Misinformation Effect

In 1978, three researchers from the University of Washington and the University of Houston conducted a study in which 195 students were shown slides depicting a car stopped at either a stop sign or a yield sign. The students then filled out a 20-question sheet containing one question that mentioned the presence of either a stop or a yield sign. For 100 of the subjects, the sign specified in the question was incorrect.

Students were then shown two slides—one with a stop sign and one with a yield sign—and asked to choose the image that they’d seen earlier. Those who had been given the misleading questionnaire chose the correct slide only 41 percent of the time; roughly half the rate of those with the consistent questionnaire, who were correct 79 percent of the time. For many of the students, the misinformation in the questionnaire had altered their visual memory to include the incorrect sign.

A similar study conducted in 1988 yielded similar results. Researchers showed participants slides depicting a burglar stealing a hammer from someone’s office. Then they read a brief report of the incident. Some of them were given reports correctly mentioning a stolen hammer—or more generically, a stolen tool—and others were given reports incorrectly mentioning a stolen wrench. They were then given a test which included a question about the stolen item in which they could choose either “hammer” or “wrench.” Those who had read the misleading report chose the correct tool only 43 percent of the time, compared to a 74 percent accuracy rate from those that had read a report with the generic term “tool.” “Misled subjects,” the authors remarked, “responded as quickly and confidently to these ‘unreal’ memories as they did to their genuine memories.”

It can be argued that these events weren’t consequential enough to be readily remembered. Clearly, a bored college student misremembering pictures on a slide is very different from a victim misremembering the details of a sexual assault or other crime. Taking this into account, psychologists developed a term specifically to describe the memories of such traumatic events: flashbulb memories.

Flashbulb Memories

A flashbulb memory is a memory encoded in a time of intense psychological stress that is supposedly extraordinarily vivid and accurate, like a snapshot illuminated by the light of a camera’s flash. While not mentioned by name, this is the type of memory to which psychiatrist Richard Friedman is referring in his New York Times article, “Why Sexual Assault Memories Stick.” Interestingly, he cites only one study—which involves participants reading an “emotionally arousing short story”—to back up his claim that trauma leads to memories that are “indelible.”

This claim runs in direct contradiction to the majority of research on flashbulb memories. As researchers McCloskey, Wible, and Cohen have noted, flashbulb memories use the same neural mechanisms, decay at the same rate, and are no more nor less accurate than typical memories overall. The only notable difference seems to be the confidence with which people speak about their flashbulb memories.

However, not all researchers agree that flashbulb memories operate via the same neural mechanisms as typical memories, nor do they all agree that they are so similar in accuracy. In fact, many researchers argue that flashbulb memories are less accurate.

In a 2013 study, New York University neurologists Christina Alberini and Joseph LeDoux examine memory reconsolidation, in which the act of reconstruction at the time of retrieval leaves a memory “susceptible to change” each time it is remembered. Operating under the assumption that different kinds of memories are stored via different mechanisms, Alberini and LeDoux demonstrate that amygdala-dependent memories—those based on threat conditioning and intense fear emotions like in “flashbulb” memories—might be more susceptible to disruption and alteration via reconsolidation.

So, while these flashbulb memories might be described more vividly and with greater confidence than a typical memory, each of the details is no more—and probably less—accurate than those of a normal memory. It is not so much like a camera’s snapshot of an event as it is like an impressionist painter’s interpretation of it. As City University of London professor of psychology Mark L. Howe explained in a 2013 paper entitled, “The Neuroscience of Memory Development: Implications for Adults Recalling Childhood Experiences in the Courtroom”:

There is another ‘common sense’ belief about memories of stressful and traumatic experiences, namely, that they are protected from being lost or distorted (…) Indeed, stress and trauma can have either a positive (memory enhancing) or a negative (memory impairing) effect: extreme levels of stress impair memory, whereas moderate levels can strengthen memory. Although hormones released during stress (e.g., epinephrine, cortisol) modulate consolidation and memory strength, this does not mean that these memories are immune to forgetting, distortion, or even possible erasure. In addition, stress impairs retrieval, particularly of autobiographical memories, and stress during reconsolidation can also lead to systematic distortions.

A natural question to ask in the face of this might be, “Even if a traumatic memory is naturally more susceptible to disruption, wouldn’t that be countered by the fact that you’d likely think of it more often than a typical memory?” It is a reasonable question, once again based on common sense notions of memory. Shouldn’t frequent remembering and/or rehearsal of a memory protect it from deterioration? As is normally the case when attempting to apply common sense to memory science, the evidence shows the exact opposite to be true.

Memory Rehearsal Increases Forgetting

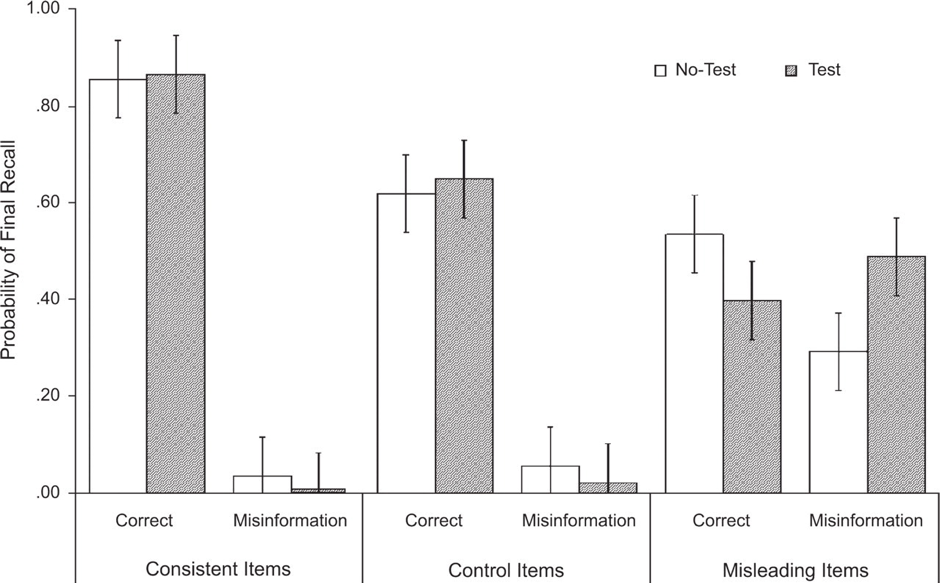

In yet another variation of the misinformation studies mentioned above, researchers had students watch an episode of 24, which none of them had seen before. In this episode, a terrorist knocks out a flight attendant with a syringe. Some of the students were immediately given a non-multiple choice recall test including questions such as, “What did the terrorist use to knock out the flight attendant?” while the rest played Tetris for the duration of the test. Then, all of the students listened to an 8-minute narrative of the video, with some of the narratives containing factual information, (e.g. knocked out with a syringe), some containing misinformation, (e.g. knocked out with chloroform), and some containing neutral information which didn’t specify the method used to knock out the attendant. Finally, all students took the same recall test mentioned above, with those in the initial testing group taking it a second time.

The experimenters initially believed that those who were immediately asked to recall the episode would be more greatly protected from future misinformation about it. What they found instead was the opposite: taking the test the first time did not protect students from the misinformation effect. In fact, those who had taken the test previously were more likely to be influenced by the misinformation.

These findings are consistent with the findings of researchers Alberini and LeDoux, who found that each retrieval of a memory leaves it susceptible to alteration. Thus, memories that are called upon quite frequently—as traumatic memories often are—will decrease in accuracy at a more rapid pace than those that are retrieved less often. Over a long enough period of time, this can lead to a memory that’s virtually unrecognizable when compared to the original event. “When memories are retrieved they are susceptible to change, such that future retrievals call upon the changed information.”

Naturally, these inaccuracies in memory can have devastating effects in a courtroom.

Prevalence of Wrongful Convictions via Eyewitness Misidentification

In 1992, the Innocence Project was founded in response to the large number of falsely incriminated individuals that were being exonerated due to advancements in DNA testing and analyses in criminal investigations. Since then, they have documented 362 cases in which a prisoner was exonerated due to exculpatory DNA evidence. These innocent people served an average of 14 years in prison for crimes they did not commit.

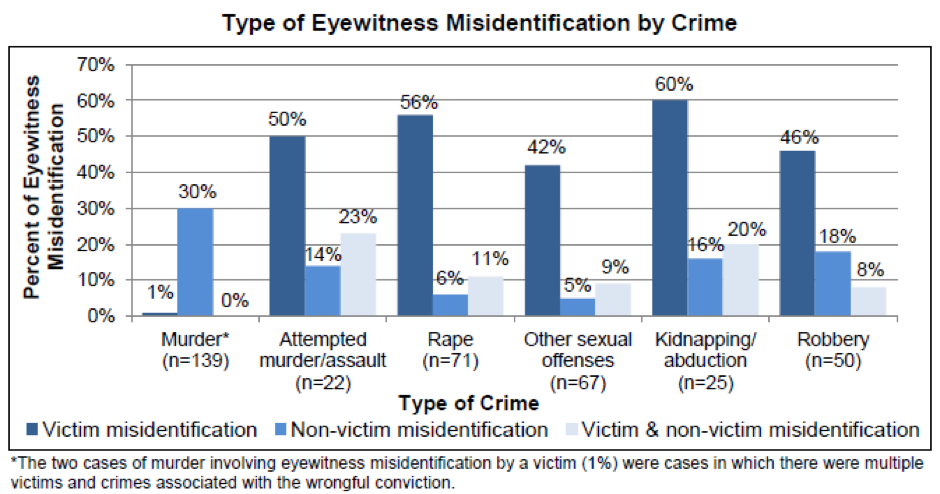

By far, the leading cause of false imprisonment in these cases was eyewitness misidentification, which played a role in 70 percent of the convictions. Nearly half of those misidentifications (46 percent) involved multiple eyewitnesses “identifying” the same, innocent person. Separate findings noted in the case of Perry vs. New Hampshire suggest that as many as one out of every three eyewitness identifications are incorrect.

Contrary to what one might expect, a 2013 study found that eyewitness testimonies of victims are far more likely to play a role in wrongful convictions than those of bystanders. (It should be noted that in the case of sexual assaults, this is partially attributable to the prevalence of cases in which there is no non-victim eyewitness.) Out of 71 people wrongfully convicted of rape, 73 percent were misidentified by an eyewitness. 92 percent of these misidentifications were by the victim alone or both the victim and a third party eyewitness, making victims four times more likely to be the one who had misidentified the perpetrator (only 23 percent of misidentifications were by a third party).

In a smaller sample of 22 cases (9 of which were of rape), 52 percent of victims actually knew the wrongfully convicted person prior to the crime. Though this sample is too small and the data too scant to make any accurate predictions about the percentage of misidentifications of known persons on a larger scale, it is enough to suggest that this is something that can and does happen given that 90 percent of reported sexual assaults are by someone previously known to the victim.

Of course, much of this depends on the broad definition of a “previously known person.” For example, it would likely take an extraordinary set of circumstances for a person to misidentify a close friend as their attacker. However, studies have shown that our recognition of casual acquaintances—people we may see quite often but with whom we rarely interact—is often no better than chance.

In a study of “Non-Stranger Identification,” researchers tested 157 high school sophomores and juniors in a small, private high school on their ability to recognize the faces of students who were seniors during their freshman years (for the juniors, those that had graduated two years prior, and for the sophomores, those that had graduated the previous year). While most of these would not have been close friends of the participants (those with family members in the classes were excluded), they would have come in casual contact with them on a daily basis over the course of the school year.

The participants were shown 50 senior yearbook pictures that would either be of students from their own high school or students from a distant high school, and they were then asked to determine whether each of the images was “familiar” or “unfamiliar.” Amazingly, participants only correctly judged former students from their own high school as “familiar” 45 percent of the time, while they falsely judged students from other high schools to be familiar 28 percent of the time. In the words of the researchers, these results suggest that “an eyewitness’s report that he can recognize a perpetrator because he has seen him casually in the past is of dubious reliability.”

The faults of memory are clear, and their influence on the accuracy of eyewitness testimony equally so. But the failure of memory is not the only source of inaccuracy. The second source, while less palatable—and likely less prevalent—is unfortunately more in line with “common sense” expectations. But, while the #MeToo movement has thankfully reduced the tendency towards this assumption, it is still undoubtedly a possibility that must be considered in each and every criminal case.

False Accusations

In 2006, an exotic dancer and escort by the name of Crystal Mangum accused three lacrosse players at Duke University of sexually assaulting her. Durham District Attorney Mike Nifong suggested that the white lacrosse players should also be charged for a hate crime against Mangum, who is black. The accusations turned out to be false. Nifong—who had allegedly used this case as a means to gain publicity in the midst of his campaign to retain his seat as North Carolina’s DA—was disbarred for his improper handling of the case. Mangum suffered no penalty for her false accusations, but she would later go on to be convicted for murdering her boyfriend and sentenced to 14–18 years in prison five years after the Duke incident.

In 2014, Rolling Stone ran a story about a woman who claimed to have been a victim of gang rape by a University of Virginia fraternity. In 2015, the magazine was forced to retract the article when the allegations turned out to be false, and the Columbia Journalism School issued a report which stated that the magazine did not employ “basic, even routine journalistic practice” to verify the accuser’s claims. The fraternity filed a defamation lawsuit against Rolling Stone, which would eventually settle the suit with a payment of $1.65 million.

Over the course of the last year alone, a woman was sentenced to ten years in prison for making a series of false allegations of sexual assault and rape against a total of 15 men in the U.K. A New Jersey man filed a $6 million suit against a woman who had accused him of rape—an accusation that led to his expulsion from Syracuse University. After “a months-long investigation, which included a medical exam, rape kit, and bloodwork within 26 hours of the incident, found no evidence [she] was assaulted, drugged or even had a sexual encounter with [the man].” Nine current and former Minnesota football players have opened a defamation and discrimination suit against the university after four players were expelled and one suspended following a Title IX investigation when a subsequent police investigation led to no charges by the county attorney office for an alleged gang rape.

Still, it’s reasonable to argue that these were simply extreme or unusual cases that garnered disproportionate media attention. Confronted with stories like these, activists routinely point to data that shows the rate of false claims is only about 5.9 percent. However, they invariably neglect to mention that this figure only covers those cases that were unequivocally proven to be false by authorities. It does not include cases dropped due to insufficient evidence or otherwise left unresolved because the victim withdrew from the process, or was unable to identify the perpetrator, or mislabeled an incident that does not fit the legal definition of sexual assault. The number of cases that fall into one or more of these categories is 44.9 percent, not including the 5.9 percent figure, above. It’s therefore impossible to tell what the true percentage of false accusations is, but even a 6 percent (or one in 17) chance that an innocent person may be convicted ought to be too great a risk.

Without corroborating evidence, a false memory would be impossible to detect, especially given the tendency for such memories to be held with a particularly unusual sense of certainty. But isn’t there at least a surefire way to detect an outright lie?

Can Polygraph Tests Ensure Accuracy?

In short, no. The popular use of the term “lie detector” in reference to a polygraph test is somewhat of a misnomer. Polygraphs measure changes in physiological arousal, such as increases in heartrate, blood pressure, or sweating. The idea is that a lying person might feel anxious due to fear of being caught, leading to such arousal. There are at least three problems with this method.

The first is that if a person does not fear being caught or does not have an emotional reaction to their own lie—e.g. a person who is familiar enough with the methods of a polygraph not to fear it or a person with sociopathic tendencies—the polygraph will obtain no significant reading. The second is that a person might feel anxious even when telling the truth due to the intimidating nature of the polygraph or when questioned about a traumatic event, leading to a false positive reading. Finally, if the interviewee is already in a particularly emotional or otherwise physiologically aroused state—which often happens when one is questioned about a traumatic event—any further increases in arousal due to a lie might be too small for the polygraph to obtain a significant reading.

A polygraph may be an accurate method of measuring changes in physiological arousal, but it cannot give a definite reason for that arousal. In other words, it cannot actually detect a lie. This is why, in a survey of members of the Society for Psychophysiological Research and Fellows of the American Psychological Association:

Most of the respondents believed that polygraphic lie detection is not theoretically sound, claims of high validity for these procedures cannot be sustained, the lie test can be beaten by easily learned countermeasures, and polygraph test results should not be admitted into evidence in courts of law.

So, while a person’s answers to questions given during a polygraph test may be used as evidence in a court of law, the readings of the polygraph itself are generally considered inadmissible. The purpose of the polygraph is not to use the readings, but it is more generally used to test whether a layperson unfamiliar with its methods would be willing to take a so-called “lie detector test” in the first place. As Houser and Dworkin noted in their paper, “The Use of Truth-Telling Devices in Sexual Assault Investigations”: “The debate around the accuracy of truth-telling devices is a central reason for the VAWA 2005 provisions limiting the use of such devices with victims of sexual assault.”

Polygraphs do not serve the function that most people tend to assume. Outside of the world of science fiction, there is no such thing as a true “lie detector.” Sexual assaults, generally being particularly traumatic and emotionally disturbing, are the perfect storm of confounding variables, making these polygraphs even less useful. This is only one of many aspects which make sexual assault cases particularly difficult to navigate.

The Unique Difficulty of Sexual Assault Cases

Sexual assault often carries with it severe psychological trauma for the victim; trauma which long outlasts any physical damage from the attack. For this reason, it is vastly underreported, with estimates placing the number of unreported rapes at 69 percent. When it is reported, the difficulty of obtaining hard, physical evidence leads to only an 18 percent chance that the report leads to an arrest. And, even when there is an arrest, the punishment is often inadequate, with fewer than 11 percent of arrests leading to incarceration. The mandatory minimum sentence for a first degree sexual assault can be two, five, or ten years, depending on the circumstances, which means it is often less than or equal to the minimum sentence for the sale of marijuana.

All of this combined with the rarity of supporting physical evidence and/or a third party witness in cases of sexual assault makes the evidence against the validity of eyewitnesses—victim or non-victim—all the more troublesome. It is imperative that the needs of victims are addressed, giving them the proper encouragement and support through a highly traumatizing experience. Admittedly, knowledge of the fallibility of eyewitness testimony may do more harm than good in some ways, only serving to further detract victims from reporting an assault.

But it is also important to acknowledge the seriousness of the allegation, as it is one that will often ruin the life of the accused even if they are found to be innocent. It is important to acknowledge that an uncorroborated eyewitness testimony runs the serious risk of leading to an innocent person being incarcerated. At the very least, even in the face of inadequate evidence, an acquitted person will always carry an accusation of one of Western societies’ most stigmatized crimes.

It is a uniquely difficult field to navigate, but there must be a balance between believing the accuser and the presumption that the accused is innocent. It is both logically impossible and vitally important that both of these beliefs be held simultaneously. This is why we must be scrupulous when weighing the evidence in support of either presupposition.

The Importance of Corroborating Evidence

We tend to treat our memory of an event as the whole picture—as something concrete—because it is our whole picture, and we consider ourselves concrete. But neither of these beliefs is true; we are as malleable as the memories that define us. Our views of ourselves and the world change, and our memories are altered accordingly. For this reason, Mark Howe argues:

Whether the witness is a child or an adult, all memory-based evidence is reconstructive. This is because memories are not veridical records of experience but are fragmented remnants of what happened in the past, pieced together in a “sensible” manner according to the rememberer’s current worldview.

The burden of proof in law does not exist only for the sake of a more entertaining courtroom drama. It exists because prosecuting someone without corroborating evidence—because the accuser seems believable—often leads to innocent people going to prison. Whether it be by a victim or by a third party, eyewitness testimonies are by far the least reliable form of criminal evidence. There is some risk of misidentifying a perpetrator even with testimonies by multiple eyewitnesses, but there is no scenario more likely to lead to false incrimination than a prosecution based on a single, uncorroborated account. There is no scenario more likely to end in the loss of an innocent person’s freedom and the subsequent destruction of their life. All of this must be considered in the judgment of Brett Kavanaugh.

The Case of Kavanaugh and Ford

The importance of the case of Kavanaugh and Ford is the precedent that it will set. This is not a movie, in which the authorities know the mob boss is guilty, but just can’t seem to nail him for his crime. This is two people who both have a legitimate case to make, and neither can prove or disprove the other’s claims. It is possible that Ford’s allegations are true, and to deny that possibility is to admit bias in the case.

However, to deny the possibility that Kavanaugh is innocent would require a similar bias. Were he on trial, he would not be convicted unless that possibility can be disproved beyond a reasonable doubt. Even if Ford is right, it’s not enough to take one person on their word, as the law states that a court must operate on the presumption of innocence with respect to the accused. Memory is not so infallible that one person’s account of an event 36 years ago is sufficient to overcome that presumption. This law is in no danger of being changed.

But, as individuals making personal judgments about the truthfulness of Kavanaugh and Ford, we are not held to the same standards as our justice system. While the law on the burden of proof is clear, we are free to believe whatever we choose. Will we choose to align those beliefs with the law and say that people are “innocent until proven guilty?” Or will we be harsher in our judgment; quicker to presume guilt than those who carry a gavel? To answer this in a fair-minded manner, it is important to remember why our laws were written to favor the defendant.

Accusations are not always justly made, and even when they are, they may be misattributed based on the malleable and reconstructive nature of human memory. Lawmakers and enforcers do not want to risk ruining the life of someone who they can’t be sure, “beyond reasonable doubt,” is guilty. So, as our knowledge in the field of memory science and the wealth of troubling statistics concerning the inaccuracy of eyewitness accounts continue to grow, trust in both is justifiably waning, and a preference for physical evidence has strengthened. For it is better to risk a guilty man going free than to risk an innocent man losing his freedom. Or, more aptly, it is better to risk a guilty man’s reputation remaining untarnished than to risk ruining the life and career of an innocent one.