Arts and Culture

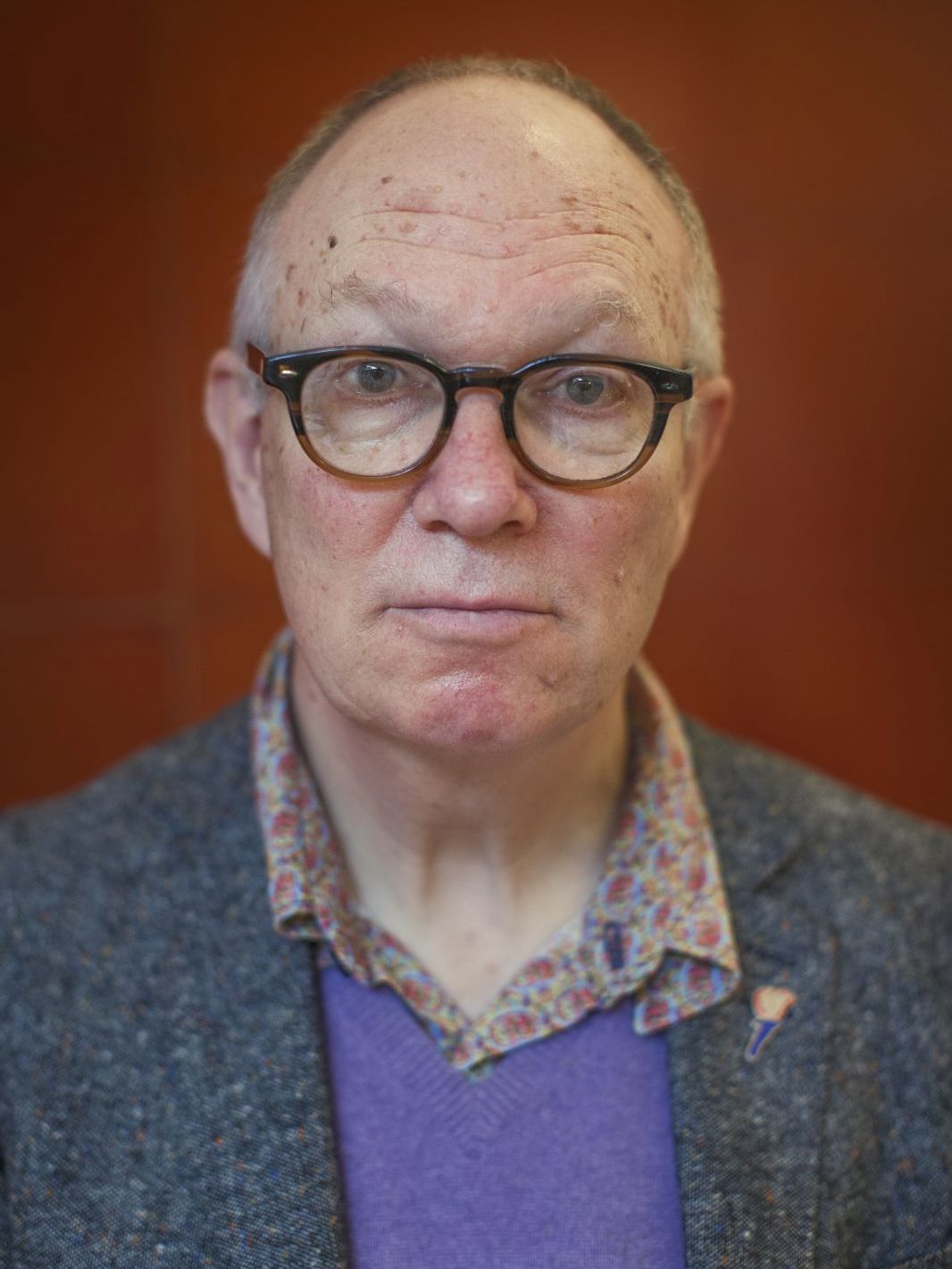

#MeToo Casualty Ian Buruma Was the Editor We Needed

I’m not the only reader left longing for an editor who displays a lordly disregard for public opinion

In September 2014, I flew to Toronto to record a series of podcast interviews with a few of the city’s cultural figures, mostly writers, all of whom I’d reached out to either because I already admired their work or because they came to my attention through trusted recommendations. The sole exception was also the one interview that fell through: with Jian Ghomeshi, host of Q, the CBC’s most popular radio show. Although I’d only heard a few of his broadcasts, Ghomeshi seemed too famous, and too closely identified with the city that would give these conversations their unifying theme, to ignore. But the arrangements proved unusually complicated, and a week before my flight one of Ghomeshi’s enthusiastic-sounding team—I remember e-mailing with an Ashley, a Debra, and a Cait—informed me that, “Unfortunately, we aren’t able to fit this in his schedule this trip, but please don’t hesitate to let us know if another opportunity presents itself in the future.”

No opportunity to interview Ghomeshi, at least the Ghomeshi Q listeners knew, would ever present itself again. While in Toronto, I mentioned my attempt to a friend who has spent much of his life in close proximity to the Canadian entertainment industry. “Oh, Jian,” he said, shaking his head, his tone a mixture of disappointment and resignation. From his subsequent elaboration I gathered that Ghomeshi was well known for his boorish behavior, especially toward women, during both his career as a broadcaster and his time as a musician before that. Though I’d never heard any rumors to that effect before, it didn’t exactly surprise me: something about the apparent pains he took to be seen publicly projecting just the right sensitive, tolerant attitudes—his ‘virtue signaling,’ as such behavior was not yet widely labeled—struck me as unseemly, in the same way that the loudest and longest moralizing on the part of a certain kind of American politician always seems to precede the revelation of his utter depravity.

The CBC suddenly fired Ghomeshi just a few weeks later, and the following month he turned himself in to the Toronto police, facing four counts of sexual assault and one of the even nastier-sounding “overcoming resistance by choking.” In Canada, this all became Trial of the Century material. But in the rest of the world, where most people first learned of Ghomeshi when he fell from grace, only spared its attention for the charges (three more of which, related to three more women, came in January 2015) and the verdict. Along with his decision to acquit Ghomeshi completely, Justice William Horkins also delivered a damning assessment of the credibility of the women who took the stand against him. “The evidence of each complainant suffered not just from inconsistencies and questionable behavior, but was tainted by outright deception,” said Horkins. “The harsh reality is that once a witness has been shown to be deceptive and manipulative in giving their evidence, that witness can no longer expect the court to consider them to be a trusted source of the truth.”

“My acquittal left my accusers and many observers profoundly unhappy,” writes Ghomeshi in the October 11 issue of The New York Review of Books,his first public statement on the matter in the four years since his firing. “There was a sentiment among them that, regardless of any legal exoneration, I was almost certainly a world-class prick, probably a sexual bully, and that I needed to be held to account beyond simply losing my career and reputation.” Ghomeshi’s essay, entitled “Reflections from a Hashtag,” was published as one of three pieces on the issue’s theme, “The Fall of Men.” In it he describes the “contemporary mass shaming” he continues to receive years after what has come to look like a Pyrrhic victory in court. “One of my female friends quips that I should get some kind of public recognition as a #MeToo pioneer,” he writes. “There are lots of guys more hated than me now. But I was the guy everyone hated first.”

I found out about Ghomeshi’s essay, which had begun circulating on the internet well before its appearance on the Review‘s front page, when I saw Ian Buruma’s name trending on Twitter. Naturally I feared he had died, a common reason for a sudden spike in tweeting about public figures of a lower profile than Donald Trump or Kim Kardashian, and certainly of the profile of a respected writer on the history and politics of Europe and Asia. And even if he hadn’t, this being the #MeToo era, I wondered if he had suffered that modern variety of professional death caused by an accusation of some kind of personal misconduct. When that happened to Jian Ghomeshi, Harvey Weinstein, Kevin Spacey, Louis C.K., or any of the other fallen men in whose work I had no particular investment, I could look the other way. When it happened to Charlie Rose, ending at a stroke his long-form television conversations that inspired me to launch my own interviewing career, I couldn’t help but take notice. If it were to happen to someone like Buruma, with whose writing I’ve professionally engaged for more than a decade now, I would have to recalibrate the distance I’ve kept from these issues.

My first contact with Buruma came in 2009, when I interviewed him on the public-radio interview show I hosted at the time. I invited him on after having read his work for some years, and I’ve continued to keep up with it, and occasionally reference it in my own writing, ever since. This past summer I reviewed A Tokyo Romance, Buruma’s memoir of his years living in Japan in the 1970s, in the Times Literary Supplement. He had succeeded the late Robert Silvers as editor of the Review the previous year, and his fans, I wrote, would watch with great fascination to see how he adapts to his role at the top of American letters. Telling the story, in his own tribute to Silvers, of how an offhand pitch for an essay on modern Japanese literature in the early 1980s led to his long professional association with the Review, Buruma wrote that his “life as a writer owes everything to Bob’s editorship,” and it seemed he would more or less carry on the legacy of his superhumanly dedicated predecessor, who had edited the magazine since its foundation in 1963.

The trending Buruma, as it turned out, was still alive and free of the taint of sexual impropriety. What got him trending was his decision to publish Ghomeshi’s essay, or rather his justification for doing so as presented in an interview with Slate. “I was interested in the subject,” Buruma said, of “what it was like to be, as it were, at the top of the world, doing more or less what you like, being a jerk in many ways, and then finding your life ruined and being a public villain and pilloried. This seemed like a story that was worth hearing—not necessarily as a defense of what he may have done.” It also points to an increasingly important truth of our times: “Nobody has quite figured out what should happen in cases like his, where you have been legally acquitted but you are still judged as undesirable in public opinion, and how far that should go, how long that should last, and whether people should make a comeback or can make a comeback at all—there are no hard and fast rules. That’s an issue we should be thinking about.”

It’s also an issue that few who responded to the interview have shown any interest in considering. Instead, they have preferred to hold Buruma’s statements on Ghomeshi’s behavior up for ridicule. To name the most frequently sneered-at example: “All I know is that in a court of law he was acquitted, and there is no proof he committed a crime. The exact nature of his behavior—how much consent was involved—I have no idea, nor is it really my concern.” Worse, Buruma had the effrontery to describe sexual behavior as “a many-faceted business.” The least responsible of the respondents have seized the chance to dig up one of his Guardian pieces from 2002 and willfully misread it as a defense of child pornography; others have questioned Buruma’s competence as an editor, signing off as he did on Ghomeshi’s use of the word ‘several’ to describe how many people have accused him of sexual misconduct, instead of specifying that there were at least twenty.

At the core of these various objections lies the idea that, by publishing Ghomeshi’s essay, the Review deviated from a tacit agreement. That agreement holds that, because the court of law had failed to punish Ghomeshi—still perceived in many quarters as a little better than a violent serial rapist who slipped justice on a technicality—it falls to the court of public opinion to deliver his punishment instead. The Review, an influential publication widely regarded as property of the American Left, was expected to comply by, if not actively attacking the men targeted by the #MeToo movement, then at least refusing to run anything speaking in their favor, and certainly not providing them a ‘platform’ from which they might speak for themselves. In publishing Ghomeshi it effectively went rogue, which in retrospect must have been what those who last year expressed reservations about Buruma’s relative lack of editing experience (not that anyone alive could have touched Silvers in that department) were worried about.

Someone like Buruma might not understand how much more a verdict in the court of Twitter counts than a verdict in a court of law. He might not understand how obsessively he needs to track and follow the impulses of the moment (or, as a tweet by the New Yorker‘s Jia Tolentino put it, not to keep a “pathological distance from the texture of the world”). He might not understand how much deference he needs to show to the power of certain social-media movements. He might not understand how much contrition he needs to show when the public, actual readers of the Review just as well as those who have never laid eyes on a page of it, takes exception to his editorial decisions. He might not understand how wrong it looks simply to be a highly educated straight white man over 60—let alone one who has written extensively on cultures not his own (his own being that of the Anglophone Dutchman), a potentially objectionable act in and of itself—in a position to decide who gets published and who doesn’t.

Perhaps these qualities made the brevity of Buruma’s tenure atop the Reviewinevitable. He resigned less than a week after he began trending, but if the Ghomeshi contretemps hadn’t unseated him, another issue eventually would have done so. Yet these same qualities also made him just the editor a publication needs in our internet-addled times. Upon his appointment, Buruma described the Review under Silvers as “a monarchy” and speculated that he would make it “a slightly more democratic operation.” He should not have discarded the crown. I’m not the only reader left longing for an editor who displays a lordly disregard for public opinion, readerly opinion, even my own opinion—a longing, in other words, for a gatekeeper, a word rendered dirty in recent years. In current usage it seems to mean something along the lines of an illegitimately privileged individual who denies the less privileged a voice, just as ‘nuance’ has come to mean the deliberate obfuscation of supposedly obvious moral truths.

In an age that has reduced so many editors to leaves in the wind of ideological fads and political fashions, Buruma showed the potential to do the job from almost as Olympian a perspective as Silvers, despite the very different path by which he arrived there. “Japan was the making of me,” Buruma writes in A Tokyo Romance, describing how his experience living there led to his first professional writing gig, which led to his first book deal, which led to a career first writing about Japan and ultimately about a much larger set of themes: culture, religion, identity, conflict, and civilization itself. But something of the Japanese sensibility, and the imperviousness it grants to the sociopolitical squabbles of the West, has stayed with him to this day. As Roland Kelts recently wrote in the TLS, “The sex and race-driven identity politics currently animating and, to my mind, diminishing the literature and cultural products of the West are either muted or non-existent in Japan, where postmodern aesthetics are the outer skin of a modernist backbone,” where creators still think seriously about “personal not political identities, and questions of the soul.”

Whatever else in Buruma’s background qualifies him to edit an internationally minded (and, in its way, modernist) magazine like the Review, the fact remains that he has produced a body of some of the clearest, most incisive writing and thinking on East and West of the past century, one that rivals the work of any intellectual alive. He is my better, probably your better, and certainly the better of those who have most loudly hailed his resignation, yet the pile-on has driven even otherwise intelligent commentators to childish insults. Around the same time as the Reviewposted “Reflections from a Hashtag,” Harper’s posted a thematically similar essay entitled “Exile” by John Hockenberry, another public radio host brought low by #MeToo. On an episode of his podcast Canadaland (entitled “Nice Work, Twitter Mob!”), media critic Jesse Brown discusses and finds wanting the explanation for running it offered by Harper’s publisher Rick MacArthur, going on to include Buruma’s remarks on Ghomeshi’s piece. “He also sounded so stupid,” Brown says. “Like, these are supposed to be the smartest guys.” Then, from co-host Anne Kingston: “All of this conversation has exposed the fact that these august publications are being run by out-of-touch, kind of creepy guys.”

In a way, Brown is right: Buruma did do something foolish—not so much running Ghomeshi’s essay or defending its publication, but submitting to the interview that sealed his fate in the first place. That the editor of the New York Review of Books would consider himself answerable to Slate‘s inquisitor beggars belief. The utter impossibility of imagining Silvers doing the same makes it look almost like an affront to the dignity of the office. But, having resigned, Buruma has at least shown a highly admirable unwillingness to issue yet another example of that increasingly frequent, abject, and emblematic form of our times, the public apology. He did, however, remark on the irony of the situation in a brief interview with the Dutch magazine Vrij Nederland soon after the controversy erupted: “I published a theme issue about #MeToo-offenders who had not been convicted in a court of law but by social media. And now I myself am publicly pilloried.” Even so, he added, “I still stand behind my decision to publish.”

Buruma stepped down, he said, because of the fears of the Review and its publisher: “They are afraid of the reactions on the campuses, where this is an inflammatory topic. Because of this, I feel forced to resign—in fact it is a capitulation to social media and university presses.” That they felt such pressure despite the paucity of evidence of an imminent university-press advertising boycott (driven, presumably, by the sensitivities of the students before whom the universities prostrate themselves) reveals a startling frailty on the part of the Review, a publication known in recent years for its comparatively rude financial health, especially by the standards of the America’s sickly herd of general-interest magazines. If #MeToo is the spectacle of a long-overdue reckoning for men in power, it’s just as much the spectacle of the drawn-out demise of the traditional media, the most threatened members of which now lash out at anything that might prolong their lives a moment longer. Their mortal peril drives them back, repeatedly and ever more desperately, to the old basely reliable subjects: sex, crime, and above all sex crime.

To my mind, the sheer sordidness of Ghomeshi’s trial and the stories surrounding it would have made for sufficient arguments against running “Reflections from a Hashtag.” Yet, according to the piece’s harshest critics, it wasn’t sordid enough: Ghomeshi had an obligation, they argue, to go into detail about the specific brutalities he was accused of perpetrating. In an ideal world, there would be no reason for the details of an individual’s sexual behavior to enter the public sphere at all, let alone a court of law. But we hardly live in an ideal world. “Now that newspapers have abandoned euphemism to describe what these people did in what they believed was private, their sexual proclivities, flooded by light, have become obscene,” Rochelle Gurstein observed in the Baffler last summer. “The latter has especially been the case with the #MeToo movement: any reader of the latest, minutely detailed article about sexual harassment that the New York Times specializes in quickly finds that he or she has been turned into a voyeur. It is no wonder, then, that the world we inhabit together feels ever more ugly, coarse, and trivial.”

But ugliness, coarseness, and triviality are no objects to many in the younger generation of writers and editors—my generation of writers and editors—replacing Buruma’s generation, bringing down the average age of media professionals by the day. Professionally forged in online environments that demand thousands of words per week on any subject that can draw a click’s worth of attention, no matter how inconsequential, they’ve hardly needed to develop a sense of the distinction between theme of the age and flash in the pan. They’ve grown up—in the West in general and America in particular—with the conception of an educated person as someone possessed, not of a particular body of knowledge, but an approved suite of opinions. An unquestioned belief in moral progress—summed up with near-parodic completeness by the self-justifying phrase “the right side of history”—licenses the view of anyone born earlier than themselves as to that extent barbaric by definition. All this has put a premium on a new variety of journalistic shamelessness, evidenced by the acclaim recently lavished on the figures most enthusiastically prepared to wade into the muck, including some roundly disdained in their profession just a few years ago.

“Ian Buruma has proved to be an outstanding editor—as accomplished in this role as he was as a writer for the Review,” declared a letter to the editors, signed by 110 of the magazine’s contributors, and published on Tuesday. “Under his guidance the NYRB has maintained the highest intellectual standards, extended its range, and expanded its body of contributors.” Calling it “very troubling” that the negative public reaction to a single article should occasion his departure, the text concludes that, “Given the principles of open intellectual debate on which the NYRB was founded, his dismissal in these circumstances strikes us as an abandonment of the central mission of the Review, which is the free exploration of ideas.” The signatories include Anne Applebaum, Ian McEwan, Joyce Carl Oates, Colm Tóibín, Janet Malcolm, Michael Ignatieff, and George Soros, accomplished figures all—and all over 50, a fair few even over 80, the generations now blithely told told to “step aside” by twentysomethings, filled with indignation and unconcerned for, if not actively hostile to, the free exploration of ideas, as well as the grown-ups who humiliate themselves seeking their favor.

“The idea of civilization that Bob personified is now under siege,” Buruma wrote in his remembrance of Silvers, and how right he now looks. Even the very word, ‘civilization,’ gives off to no small proportion of the generation born after about 1970 the stench of imperialism, racism, patriarchy, and any number of other weaponized abstractions. But Buruma’s books, which I can only hope he will continue to write, demonstrate that he truly understands civilization, its nature, its value, and its fragility, an asset that far outweighs the incongruous naivety apparent in trying to initiate a conversation on personal responsibility and redemption with a self-serving essay by a disgraced CBC host. “We have lost him just when he was most needed,” Buruma wrote of Silvers, but the Review has also lost Buruma when he was most needed. All of our serious publications, at least the ones that have managed to stay above the undifferentiated 21st-century fray of righteousness and panic, need editors like him. This media environment, as a few minutes’ scrolling through Twitter, Facebook, and now even major publications reveals, will not produce them.