Books

Barefoot Over the Serengeti: A Visit with David Read

Having lived and worked in rural East Africa for 16 years, I find that Read’s stories ring true, whereas Hemingway’s ring hollow.

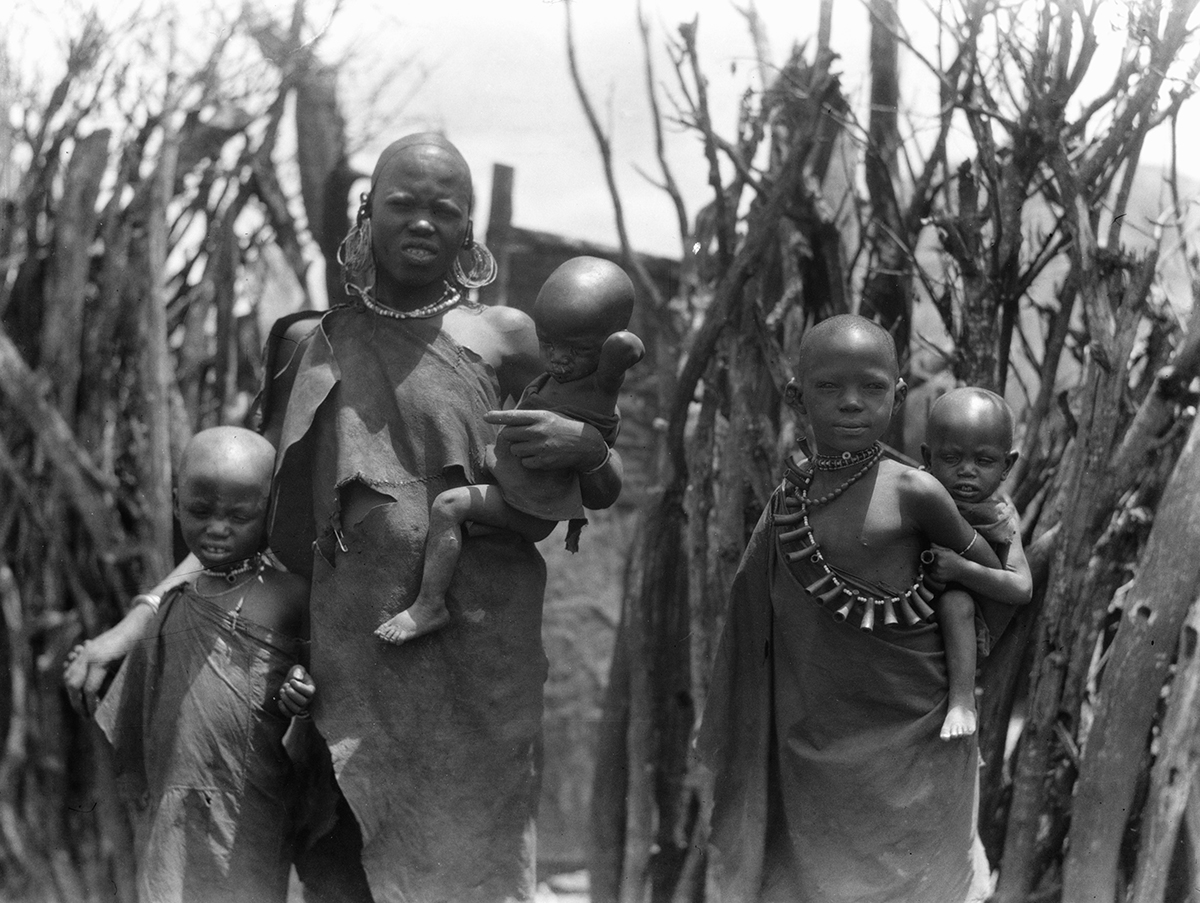

“When [the Masai] gave you their word or made a promise, it meant something,” the author David Read (1922-2015) said to me in his last days, during an interview at his home in rural Tanzania. “They were also very generous. If they were laying on a feast and you were around, you were automatically invited. That meant you ate a lot of meat and drank a lot of their beer. In the early days in [the village of] Loliondo, my mother became the local nurse to Masai for miles around. And so, when the depression hit in 1929, no one had any money, my stepfather had to go far away to try his hand at mining. Every day, the Masai delivered milk and some meat for my mother and our family. We were very fortunate, and they kept us alive.”

Read’s oeuvre—including Barefoot Over the Serengeti, Another Load of Bull, Beating About the Bush, and his novel about a Masai warrior set in pre-colonial times, The Waters of the Sanjan—evoke the life of an Englishman raised among the nomadic cattle herders of East Africa. He spent his whole life in this region, interspersed with service in the British army in Ethiopia and Burma during the Second World war, and later with short visits to the United Kingdom.

He was the son of an English couple who farmed flax in Kenya. Later, his mother opened a general store at the Loliondo trading post, on Masai land. This was just after the First World War, when the British were consolidating their hold over what is today Kenya and Tanzania—which then comprised the Colony of Kenya and the League of Nations mandated protectorate of Tanganiyka (ruled and administered, respectively, for the League by the British Crown). Soon after Read was born, his father left. And for a while, he was taken care of by his mother alone, an extraordinary woman with advanced nursing skills who, before shipping out to Africa, had been a concert pianist. She later remarried, and David was fortunate to develop a close relationship with a Czech stepfather named Otto.

As a boy, Read was footloose and unschooled. He spent his formative years among the Masai, learned their language, absorbed their customs and won many friends, including an especially close companion who would go on to become a Masai leader. As a young teenager of 14, Read was sent away to boarding school in Arusha (in what is now eastern Tanzania). He arrived barefoot and semi-literate. But eventually he learned, between fistfights, how to read and write in English, and to act and think in a British way.

As a young officer in the Kings African Rifles, Read led Masai-speaking troops drawn from the Samburu people to fight Ethiopia’s fascists. He then led the same troops in Burma against the Japanese, and returned home with them to East Africa. After the war, he worked as a big-game hunter, safari guide, cattleman, livestock officer, pilot and farmer. He married, sired a daughter, and joined the European ex-pat community of Tanganyika, which historians estimate to have been comprised of no more than 15,000 people spread across an enormous territory.

My personal encounter with Read came in 2015, shortly after I’d read (or re-read) his books during a safari I’d led through Loliondo and the same Serengeti that had so fascinated Read as both boy and man (and which is now part of a world-famous national park). It was during this same period that I’d also reacquainted myself with the white Zambian-born woman who’d been my butcher during the five years when Tanzania had been my full-time home.

Her husband had recently been killed near the Serengeti by elephant poachers. Yet there she was, as I remember her, preparing biltong by hand and helping me choose the best cuts to take with me on safari. She told me that Read lived a half hour down the road and received visitors from time to time. She added that he was now in his nineties, tired easily, and was a bit frail—but may be willing to talk to me. Soon after, I was on the phone with his charming daughter Penelope (Penny), who was visiting from her home in New Zealand, and we set up a time to meet. I could not wait.

Here is a typical passage from Barefoot, which demonstrates and distils Read’s story-telling abilities. It is written in an almost throwaway style. But upon rereading it, you realize that it could not have been expressed in any other way. It is as if his language mirrored that footloose reality that the author inhabited:

The honey-bird directs humans by calling and jumping from tree to tree, leading them to food of any sort. This is usually honey but can often be a wild animal such as a rhinoceros or even a large snake. After the human has taken what he wants of either the honey or the kill, the honey bird will pick up what is left, such as congealed blood, bees’ wax or young, undeveloped bees in the comb. So, when following a honey-bird you have to be particularly careful as you could very easily be led into danger. The Masai have often used this bird to uncover cattle thefts when they suspect there is an olpul (feast) of stolen cattle in a certain area.

Or consider Read’s description of lions on the hunt. (He had much respect for these animals, and hunted many during his lifetime.)

Just before dawn the roaring started up again. I was looking forward to the dawn and had been doing so for what seemed like a lifetime. But the new spate of roaring initiated a fresh bout of terror, worse than the fear I had felt during the night. However, with the lightening of the sky I regained some of my lost confidence, and while sitting there in the cab, my courage returning, I saw for the first time a lion kill carried out according to the book, which, strangely enough, is rare…A herd of about eight zebra was moving across in front of the lorry some fifty yards away, when suddenly three young lion charged them. The zebra panicked and swung back. They were in full gallop when a lioness who had been in hiding jumped on to the back of one, her forepaws and head on her prey’s shoulder and neck. She then leapt off and lay down a little way away. The zebra collapsed and never made another move; it was stone dead.

As I got out of the jeep in front of Read’s home, I was greeted by Penny and a small dog named Sungura, which means rabbit in Swahili. I assured her that I do not fear dogs that size, and she off-handedly remarked that this was really Sengura II. The first Sengura, I learned, had been just as frisky, and either out of friendliness or inexperience, had gotten a little too close to a venomous snake.

We walked into the living room of a large modern farmhouse that looked out toward the rolling acacia-laden hills. David was sitting upright and seemed attentive. He was about six feet tall, and must have been taller when he was younger. He seemed confident and friendly, and spoke slowly, thoughtfully and at times emphatically. I liked him from the first moment, as I expected I would. After he spoke generally about the Masai—as quoted at the beginning of this article—I asked if things were still the same in this part of Africa.

“Things have changed, and mostly for the worse,” he said into my recorder. “Then, if a Masai asked you for a cigarette, you would give him one, and then he would ask for some for his warrior-age mates, but that is no longer the case. It is now every man for himself. The Masai have lost much of their culture. And often, Masai who have not been brought up in the tradition will come to me to ask me about their customs of 70 years ago! During pre-independence times, in Masai eyes, Europeans were considered a special lot. And there were so few of us around. Take, for example, an Australian District Commissioner who I knew and who went on a many-month safari to register Masai, collect taxes and adjudicate disputes. The Masai would often debate these new rules for days before accepting them. The DC would every once in a while go off for a sleep in his tent and leave his glasses on the table. He would jokingly tell then, ‘You should all know that I am watching you.’ Yes, the Masai and many other tribes had enormous respect for the European.”

I asked him if that helped explain why so many young Masai speaking men joined up with the King’s African Rifles to fight the fascists in Ethiopia.

“Yes. By that time, I was a soldier and an officer. I was given a group of Samburu, the Masai speaking tribe of Kenya’s northern desert. They are bush people, disciplined and aware of danger. When we were on patrol in Ethiopia, they would know by the way a tree or a leaf had been touched or the way the ground had been overturned, who had been there, when and how many there were. But we had a serious problem with them. They were getting restless. They became insubordinate, and our commanding officer addressed them in public. He said something like this: ‘If you think that by complaining, protesting and acting in an insubordinate way you will get back home quickly, that will only happen if you walk home barefoot!’ They immediately threw their hats in the air, broke ranks, and the next day we started the barefoot trek back to Kenya. The commanding officer had made a promise and it could not be broken. If he did, there would have been a mutiny.”

“But that was not the end of it. A fair number of Samburu joined me in India and we fought in Burma. And yes, I did meet [famed British officer] Orde Wingate. He commandeered our officers-only hotel room in India when we were on leave, and ordered us to sleep on the floor. He said it would ‘toughen us up for the fight ahead.’ For those who have read about General Wingate, this should come as no surprise.”

I asked Read when the relationship between the Masai and the Europeans started going off the rails. His reply: “It was certainly not during the Mau Mau insurgency in Kenya during the 1950s. As a matter of fact, the Masai of Tanzania and Kenya had offered the British authorities their assistance. They said they could sort the Kikuyu out if given the opportunity and left alone to do the job. Understandably, the government refused this offer.”

“Things started going wrong, and I witnessed it personally, when some of my African soldiers went to London for a victory parade. They were shocked to see and hear about white prostitutes on the streets of London. You see, the Masai were and are a tribe where the woman has total sexual control of her body. If a single or even married Masai man approaches a woman with romantic attentions, and there are many time-honored ways that this is done among them, and he persists despite the fact that the woman says no, he may get a spear in his nether parts for being too pushy. On the other hand, once a man is married, his wife will be expected to take care of a visiting-age mate for the night with all that that entails. I never heard of complaints, and so I assume that the wife had the right to say no. One must consider that the Masai were sexually liberal. Our community was not. When a European man wanted to have an affair with a European woman, it took a lot of work and subterfuge. This was foreign to the Masai.”

I asked about what had become of Read’s many Masai friends. He replied: “My closest Masai friend was Matanda, which was his nickname. We basically grew up together and shared all and everything. But eventually, I had to become an Englishman of sorts and he became an influential, powerful and wealthy Masai leader…[But] many years later, we reconnected. I helped some of his close relatives get to a hospital, and I also took him up in the air for a plane ride. Afterwards, he sat me down and said, ‘David, I will never be able to live in your world of airplanes, but I have my cattle and will continue to herd them. You have to do what you have to do.’ But I can tell you, he was none too happy about it. I think he wanted us to go back to our old way of life together.”

I then asked Read how he diverted himself when he was not at work or among the Masai, and he answered: “There was always the [Arusha] Club. If you were a European, you were expected to join. That was where people who were widely dispersed got together. You would eat there, stay over, meet up with old friends and have drinks. That was where I would meet up with my close friends and neighbours such as Albert Levi, a Spanish [Sephardic] Jew whose parents had probably come from Germany when Tanganyika was a colony. The Tanganyikan European community was not just English. There were Poles, Danes, Czechs and what have you. It was really quite cosmopolitan, and everyone seemed to get on with each other.”

Students and historians of East African society often have described the last century in that part of the world as an unremitting Western onslaught against African traditions. I asked Read if there had been cultural influences in the other direction.

“Of course,” he said. “Among the farmers and ranchers, there was inevitably now and then labour disputes and unrest. One would think that labour negotiators would be the cure for that kind of thing, but often these things got sorted out by the local mganga, or what we in Europe would call a white witch or sorcerer. I had one on my ranch and he also specialized in fertility issues. So one day some neighbours told me that they would like to consult him. Hamza obliged and whatever it was that he did, their sister living in Wales who had been unable to conceive, got pregnant and gave birth to a child nine months later. Hamza got the credit for that one.”

In addition to reading David’s books on safari, I had brought with me and re-read Hemingway’s Green Hills of Africa, in which he describes his big-game hunting experiences in the Manyara region, just east of the Serengeti. As Read had been known as a superb big-game hunter, I asked him about Hemingway.

“Well,” he said, “I give him full marks for being a great writer. I have read many of his books. He spent a fair amount of time here and would stay at the Arusha Club for weeks at a time. We all knew he was there and saw him. One day, one of his people told me that he wanted to meet me. I showed up at the right place at the right time and waited a bit. He came downstairs late. He smelled as if he had not bathed for a week, his clothes were filthy, he reeked of alcohol, clearly he had been drinking, was rude and ill tempered. I left the club. A couple of weeks later, my contact told me he wanted to meet with me and apologize for his bad behaviour. I told him to get lost. But his son Patrick has been around over the years and he is a perfect gentleman.”

I prefer Barefoot Over the Serengeti to Hemingway’s own apparent classic about big game hunting in East Africa. Hemingway came to Africa late in life. Read was born there. Hemingway wanted to be a big-game hunter. Read was a big-game hunter. Hemingway recommended that we write about what we know. Read knew a lot more about hunting and Africa, and its people, both African and European, than Hemingway ever did, and wrote about them without bravado. Having lived and worked in rural East Africa for 16 years, I find that Read’s stories ring true, whereas Hemingway’s ring hollow.

* * *

In April 2003, David Read set out to find out what had happened over the years to his childhood best friend, the aforementioned Masai chief, whose name was Matanda. He was too late. Matanda had passed away but David discovered that he had named one of his sons David, in honour of their unbreakable friendship. This no doubt inspired these last lines from Read’s book Barefoot Over the Serengeti: “The time came for me to leave, as it was getting late. Both Halango and Aipano tried to me make me stay longer, saying I was the only father they had left. They made me promise to come back with my family. I do not know if I ever will. I am now 80 and do not travel as well as I once did. Time will tell, I guess, as always.”

I had finished my glass of water, turned off my tape recorder and thanked David and Penny for having me as their guest that afternoon. A few months later, on July 2, 2015, David Read passed away at the age of 93 and was cremated. His remains are buried in Arusha.

Over the next century of so, I predict that teachers of literature will laud three authors who successfully and poetically evoked 20th century East Africa in their writings. The first will be the Danish aristocrat Karen Blixen, author of Out of Africa. The next will be Beryl Markham, David’s friend and fellow pilot, who wrote West with the Night. The third will be David Read himself, author and subject of Barefoot Over the Serengeti. The book is a classic. And I am grateful to have shaken the hand that wrote it.