Top Stories

The 'Black Chic' Wave

To be a black Democratic candidate in 2018 is to be seen, not just as a politician, but as the next step in the decades-long march towards racial equality.

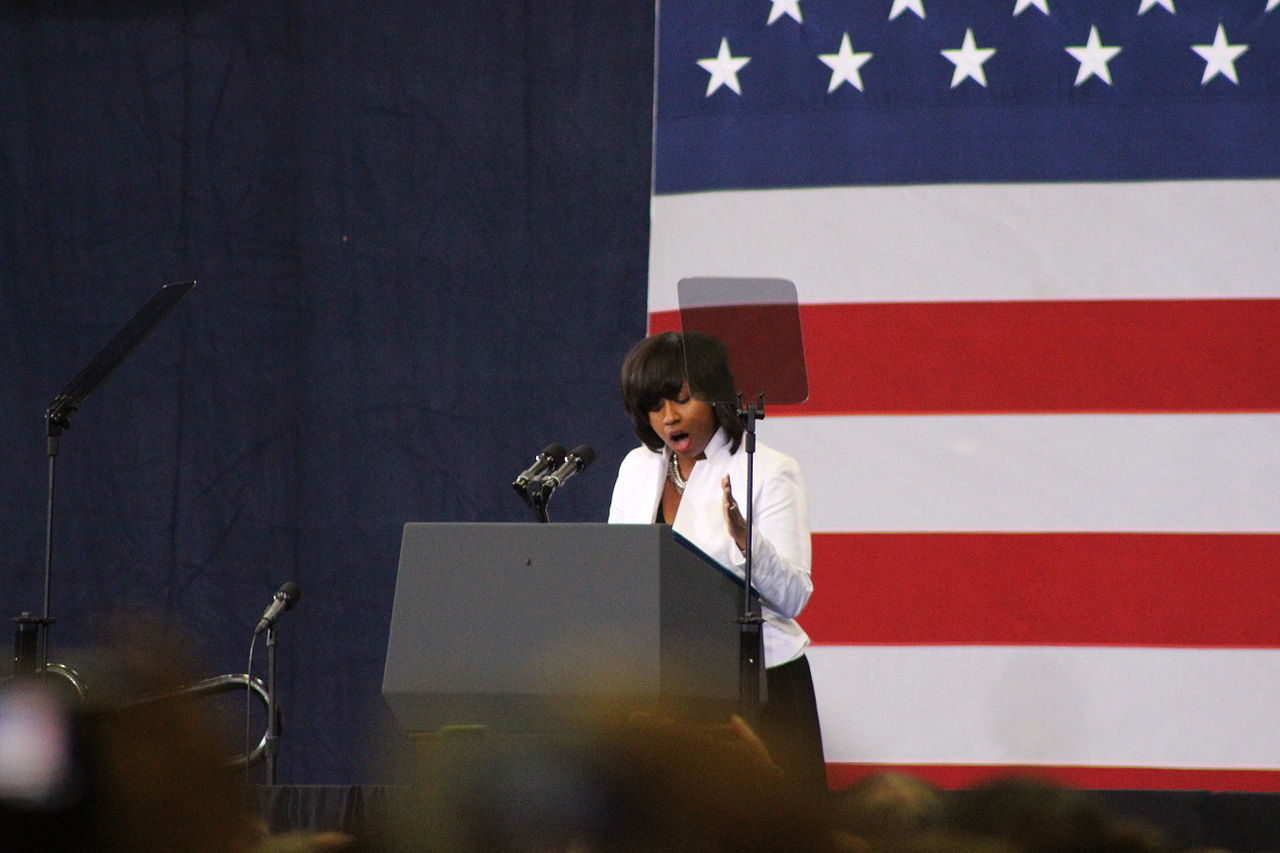

With the midterm elections approaching, political pundits have begun the hackneyed ritual of predicting wild success for their preferred party—either a ‘blue wave’ for the Democrats or a ‘red wave‘ for the Republicans. Time will tell which wave reaches our political shores. But in the meantime, a different sort of wave is already upon us: a wave of black candidates who present their skin color as if it were a political credential in itself. This new wave of ‘black chic’ candidates includes Democrats Mahlon Mitchell of Wisconsin, Stacey Abrams of Georgia, Andrew Gillum of Florida, and Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts (featured pic, above). To observe that these candidates happen to be black would be to state an uninteresting fact. What’s interesting is that—contrary to what the concept of white privilege would predict—their blackness actually gives them political advantages.

All four candidates would be the first black governors/congress people of their respective states/districts, which allows them to project a level of historical gravitas unavailable to their white counterparts. Abrams, for instance, has “frequently noted the historic nature of her candidacy,” according to Vox. “I don’t just want to make history,” Mitchell has claimed, “I want to make it count by actually doing things that help people.” On the eve of his primary win, Gillum reminded his audience that if he won he would be “the first candidate of color ever to lead a major party in the state of Florida.” To be a black Democratic candidate in 2018 is to be seen, not just as a politician, but as the next step in the decades-long march towards racial equality.

To get a flavor of how well the ‘making history’ motif is playing in some circles, here is Shaun King of The Intercept:

What we are experiencing right now is absolutely historic. The United States does not currently have a single black governor—not one … I won’t go as far as calling this moment the new Reconstruction, but we haven’t seen the possibility of this type of political representation at the state level since the years following the Civil War.

And consider this, from an op-ed in the New York Times:

The most significant political shift in decades is happening, but it’s not Trumpism or white nationalism or corruption or even on the Right. It’s in black politics. Historic electoral wins … show the might of the black political Left.

Yet considering that we’ve already had a successful two-term black president with high approval ratings, the ‘making history’ claim rings a bit hollow at the state and district levels. The claim, however, functions less as an honest description of reality and more as a emotional transaction between voters and politicians. In this bargain, left-leaning voters get to participate in the latest battle of the War On Racism and reap all of the psychological benefits that attend this righteous struggle. On the other end of the bargain, black politicians—who are, after all, just as self-interested as politicians of any other color—get to win elections. I don’t doubt that both voters and candidates emotionally vibrate to the ‘making history’ motif. But in 2018, that motif is no longer an accurate reflection of our racial and political landscape; it is a display of ritualized anti-racism.

Not only can candidates of color ‘make history’ in a way that their white counterparts cannot, but they can also turn their melanin into money. According to Gillum’s comments in the New Yorker, the billionaire George Soros donated money to his campaign in part because Gillum was black. Here’s Gillum recounting the moment when Soros decided to back him:

Soros committed to back Gillum’s gubernatorial campaign.“If I’m remembering it correctly, it was, ‘We don’t know if you can win, but we would like what it could represent,’” Gillum said. “I interpreted it to mean that it would be significant to see a person of color taken seriously in a statewide race.”

What’s more, there is a PAC called The Collective which has raised almost a million dollars explicitly to support black candidates for public office. Since its inception in 2016, the Collective PAC “has helped 18 candidates win primary and/or general elections,” including Sen. Kamala Harris (D). On their website, the PAC endorses the reductio ad absurdum of the concept of equity by claiming that precisely 13 percent of American politicians should be black (because blacks make up 13 percent of the general population.) They’ve even converted that percentage into raw numbers. According to their math, we need exactly 275 more blacks in state legislatures, 43 more in statewide offices, 11 more in the House of Representatives, and 10 more in the Senate. Until those numbers are reached, money will continue to flow to politicians with the right amount of melanin—including Gillum and Abrams, both of whom are supported in part by the Collective PAC.

A PAC explicitly dedicated to electing white politicians would be unthinkable—or if such a PAC did exist, then all reasonable people would be in general agreement about how to view such a racialist project. Yet a PAC dedicated to electing black politicians can be mentioned in the New York Times without so much as a hint of disapproval. Of course, it’s not the same. Whites were not enslaved, subjected to lynching, redlining, and various other instruments of racial terror. But then again, neither were Mitchell, Abrams, Gillum, and Pressley, who were all born in the 1970s, and thus know more about affirmative action and diversity initiatives than they do about the middle passage or segregated water fountains.

What I’m getting at is this: How long does the fact that one’s ancestors suffered grave injustices give one the right to engage in behaviors that, in any other context, would be viewed as unethical?

Ultimately, the black chic wave says more about the changing beliefs of voters than it does about the changing ethics of politicians. Not long ago, a black candidate would have had to play down the significance of their identity and instead emphasize a color-blind universalist ethic in order to win a Democratic primary. It was Barack Obama, for instance, who said in 2004, “There is not a Black America and a White America and Latino America and Asian America—there’s the United States of America.” Today the winning strategy for left-wing candidates is to do the opposite: to play upyour blackness, your immigrantness, your womanhood, your queerness—anything that puts distance between you and the moral abyss of the straight white male.

Rhetoric once seen as fringe, counter-cultural, and rebellious is now successfully deployed in the mainstream by candidates seeking to energize their voter bases. Consider the reception Ayanna Pressley received when she invoked the concept of ‘systemic inequality’ on the congressional campaign trail in Boston:

“This is not just about resisting and affronting Trump,” she declared, garbed in a flowing red jumper. “Because the systemic inequalities and disparities that I’m talking about existed long before that man occupied the White House!” The crowd went wild (emphasis mine).

Not long ago, using rhetoric straight out of an African American studies course would have been political suicide for a Democrat in Boston. But last week, using such rhetoric, Pressley pulled off an impressive upset against Rep. Michael Capuano (D)—a white 10-term congressman whose politics were just as progressive as her own. According to Pressley’s comments in theTimes, what distinguished her from Capuano was not her politics per se but her “political style and attitude”; in other words, black chic.

In Wisconsin, Mitchell has used his blackness to gain the political upper hand as well. According to Vox, he has “ramped up his discussions of race as he’s made his pitch to voters.” In a strange reversal of white privilege, Mitchell told Vox, “I actually think being African-American helps me.” Considering the gravitas, the money, and the moral authority that comes with being a black candidate on the Left in 2018, Mitchell’s statement—as backwards as it may seem in the context of American history—rings true.

What has gotten lost in the midst of our identity craze is the idea that a politician’s race should not matter. Their policies should; their character should; their ethics should. But the amount of melanin in their skin is as irrelevant to their political competence as it would be to a surgeon’s medical competence. As the Jim Crow era recedes further into history, the level of significance that we invest in racial identity should not be increasing; it should be decreasing.

Perfect color-blindness, as a matter of human psychology, is impossible. All of us notice skin color whether we want to or not. But that’s a fact about human psychology, not a guide to what ethical ideals we should encourage. By analogy, consider selflessness. Perfect selflessness is impossible. Nobody could honestly say that their level of concern for themselves is identical to their level of concern for a stranger. But we do not let that stop us from encouraging people to strive for selflessness as an ethical ideal. At minimum, we don’t encourage people to be more selfish than they otherwise would be.

What the identitarian Left has done by disparaging color-blindness as an ethical aspiration is the equivalent of encouraging us all to be more selfish. Yes, we cannot literally become color-blind. But the goal, ethically and politically, should be to discourage the kind of color-obsession that is, and will always be, seductive to members of our species. If the black chic wave is any indication, then we are failing to achieve this goal spectacularly.