Security

Zero Tolerance at the Mexican Border

Enacting policies that provide additional border control isn’t a problem in and of itself. Immigration policies are only a problem if and when they go too far.

Under a new ‘Zero Tolerance’ US border policy, 1,995 children were separated from 1,940 adults between 19 April and 31 May in an attempt to deter further illegal crossings. The pitilessness of such a policy was bound to provoke outrage, and widespread expressions of revulsion have only intensified with the circulation of photographs of distraught children. News outlets, public figures, and people all over the world have rushed to condemned the inhumanity of the Trump administration. Is the outrage misplaced or is it justified?

By any reasonable account, it’s necessary to have and enforce immigration laws. The cultural, political, legal, and economic stability of nations depend on their ability to define and control their borders. Enacting policies that provide additional border control isn’t a problem in and of itself. Immigration policies are only a problem if and when they go too far. The new policy states that “if someone caught at the border illegally has a valid asylum claim, they could have a federal criminal conviction on their record, even if a judge later decides they have the right to stay in the country legally.” This is the policy issued by Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen, as outlined by Attorney General Jeff Sessions.

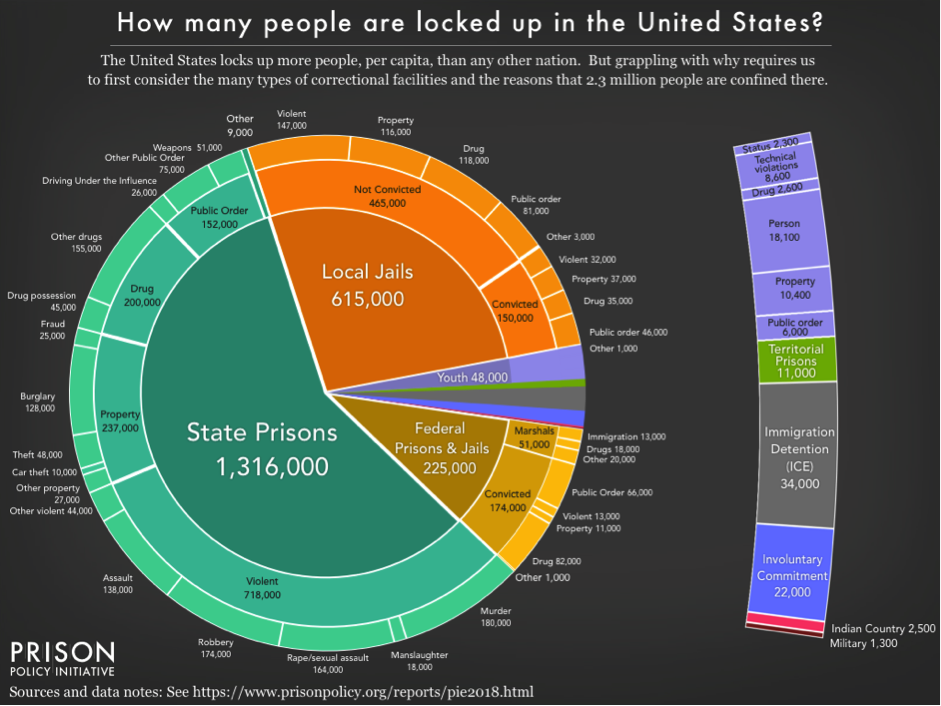

Sessions directed United States Attorneys on the Southwest Border to “prosecute all amenable adults who illegally enter the country, including those accompanied by their children, for 8 U.S.C. § 1325(a), illegal entry. Children whose parents are referred for prosecution will be placed with the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR).” Given the United States’ penchant for incarceration, and Trump’s desire to be a ‘law and order’ president, it’s unsurprising that incarceration is the default position for new US immigration policy.

Putting children into foster case or a kind of temporary housing system is standard practice when their parents commit crimes. This is true of the US and it’s true of other countries. In the US, 20,939 children are currently separated from their parents as a result of parental incarceration. That figure represents roughly 8 percent of all cases of child removal in 2016. Separation isn’t ideal, but it is better—or, at least, less bad—than sending children into prisons.

Those presently defending the new policy regard child separation to be the result of parental irresponsibility. If a parent takes the decision to cross into the US illegally, then that parent is morally responsible for what happens next, not the United States or its government agencies, and certainly not the Trump administration. If staying at home and travelling to the US both entail risk, then the parent has to make their choice and accept the consequences. But this is not the complete picture.

The UN’s Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees provides immigrants with the right to seek asylum and forbids states from deterring asylum seekers. Although states may apply necessary restrictions on movement, they may not impose penalties on account of illegal entry or presence, provided that migrants present themselves without delay and show good cause for entry. Good cause only needs to be argued for, it does not have to be legally demonstrated there and then. It should be enough to cite a plausible risk of persecution or an endangered life. The process of determining legitimate refugee status occurs after the individual in question has been provisionally accepted. Separating parents and children is therefore likely in violation of the UN Convention, unless the state has already demonstrated that the parents are there for the illegitimate reasons. If those crossing the border have voluntarily announced themselves and offered a credible reason for their flight, arresting them on the grounds of illegal entry is highly dubious. As Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, has since said, “The thought that any state would seek to deter parents by inflicting such abuse on children is unconscionable.”

On Monday 18 June, Chris Geidner, Legal Editor at Buzzfeed News, reported on a press briefing given by White House Press Secretary Sarah Sanders and Homeland Security Secretary Kristjen Nielsen. Geidner reported that Nielsen had said people need to seek asylum at ports of entry. Her statement implies that the nature of the crossing is itself a sufficient criterion upon which to base a ruling on a crossing’s illegitimacy. If a migrant or asylum seeker uses an official crossing point, then he is legitimate. If he tries to ‘sneak in’ on a raft or using other surreptitious means, then he forfeits his right to asylum. Asylum seekers who go directly to official crossing points are not typically separated from their families. In an interview with Texas Monthly, Anne Chandler, executive director of the Houston office of the nonprofit Tahirih Justice Center, offered the following explanation for why immigrants are choosing to enter between official crossing points instead:

Very few people come to the bridge. The border patrol are saying the bridge is closed. When I was last out in McAllen, people were stacked on the bridge, sleeping there for three, four, ten nights. They’ve now cleared those individuals from sleeping on the bridge, but there are hundreds of accounts of asylum seekers, when they go to the bridge, who are told, “I’m sorry, we’re full today. We can’t process your case.” So the families go illegally on a raft—I don’t want to say illegally; they cross without a visa on a raft. Many of them then look for Border Patrol to turn themselves in, because they know they’re going to ask for asylum.

Two things are worth noting here. First, it’s unreasonable to require a person to use an official crossing point if that crossing point is closed. Second, most migrants turn themselves in—the days of undetected crossings ended years ago. Surely, turning yourself in when you’ve entered at an unofficial crossing point falls into the category of “presenting to authorities without delay,” as required by Article 31. In an imperfect situation, where life is more difficult than it otherwise needs to be, innocent people, who are likely to be unfamiliar with US and international law, may be doing their best to act in good faith. So, the nature of the crossing is not a sufficient criterion for assessing its legitimacy.

Despite scathing criticism, Sessions continues to defend his ‘Zero Tolerance’ policy, saying that the policy it isn’t about “being mean” to children but about “discouraging people from making children endure that treacherous journey… Everything the ‘open borders lobby’ is doing is encouraging that and endangering these children.” I will not speculate about what is or isn’t in the heart of Jeff Sessions. But if, as he claims, the welfare of immigrant children is of paramount importance then he ought to concede that his policy is a disaster.

By taking a suspect or child into custody, the state assumes a duty of care. If a person is no longer free to act in accordance with their conception of their own best interests, the state must make a good faith attempt to do so (subject to resource constraints). In this sense, the state must be beneficent and non-maleficent; the state must do well by the people for whom it is charged to care and must avoid doing harm. These are moral principles protected by law. I’d be willing to make a further ethical claim: If the state cannot fulfil this duty of care due to resource constraints, then the state ought not to take charge of the person at all, unless doing so is essential to the safety of its citizens.

Reports about the various ways in which state institutions are failing immigrants have come thick and fast. One undocumented migrant from Honduras allegedly had her child taken while she was breastfeeding. Another report claims that the Department of Health and Human Services is considering housing separated children in tent cities on nearby army bases. Reuters reports that asylum claims made by those escaping gang violence and severe domestic abuse may not be recognised anymore, owing to Sessions’s new policy.

In the light of such reports, Sessions’s pious claim that he is protecting children sounds like a cynical means of excusing an otherwise inexcusable attempt to reduce the burden on immigration courts. Reuters reports that some 711,000 cases are currently waiting to be heard, being heard, or being appealed. No doubt, splitting families up, trying children en masse at immigration courts, and tightening up regulations helps relieve some of the strain. If the only barrier to increasing output is proper process, adding short-cuts is sure to help, or at least move the problem further down the line.

But when the problem has been moved all the way to the frontlines, chaos has ensued. In her interview with Texas Monthly, Anne Chandler says:

There is no one process. Judging from the mothers and fathers I’ve spoken to and those my staff has spoken to, there are several different processes. Sometimes they will tell the parent, “We’re taking your child away.” And when the parent asks, “When will we get them back?” they say, “We can’t tell you that.” Sometimes the officers will say, “because you’re going to be prosecuted” or “because you’re not welcome in this country,” or “because we’re separating them,” without giving them a clear justification. In other cases, we see no communication that the parent knows that their child is to be taken away. Instead, the officers say, “I’m going to take your child to get bathed.” That’s one we see again and again. “Your child needs to come with me for a bath.” The child goes off, and in a half an hour, twenty minutes, the parent inquires, “Where is my five-year-old?” “Where’s my seven-year-old?” “This is a long bath.” And they say, “You won’t be seeing your child again.” … In another case, the father said, “Can I comfort my child? Can I hold him for a few minutes?” The officer said, “You must let them go, and if you don’t let them go, I will write you up for an altercation, which will mean that you are the one that had the additional charges charged against you.”

When appropriate processes and procedures lapse, they leave the vulnerable even more exposed. Threatening parents who wish to console their children is obviously unacceptable, or at least it ought to be. Lying to vulnerable people, as an authority figure charged with meting out some degree of justice, is shameful.

Now that parents are facing questionable charges of criminality, their children are considered ‘unaccompanied.’ But those children were not unaccompanied when they arrived, they were taken from the custody of their parents by US officials. In the name of protecting children, the US is now pulling families apart, many of whom claim to be escaping domestic violence, gang warfare, civil conflict, and immense suffering.

Worst of all, the new Zero Tolerance policy has backed key decision-makers into a corner. White House Press Secretary, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, and Speaker, Paul D. Ryan, have both invoked the Flores Settlement as justification for the separation policy. But the Flores Settlement requires that officials place minors in the “least restrictive setting appropriate.” Flores stipulates three options:

- Releasing families together.

- Passing a law to allow for family detention.

- Breaking up families.

Because domestic and gang violence are no longer to be considered valid grounds for asylum, releasing families together is an easier task. When dealing with migrants in other circumstances, however, choosing between options two and three is difficult. It requires the state and the public to determine whether they prefer separating children from their families, potentially for months on end, or keeping the family together in a criminal detention centre for as long as it takes the parents to be processed and receive their day in court. Bearing in mind the number of cases being processed currently, that could take the better part of a year, at least. It seems that the only decent option is the one that the US refuses to allow—monitoring families in a setting outside of detention facilities.