Education

The Tragedy of Australian Education

The Gonski panel is the chorus and we are the audience. The play is the ongoing tragedy of Australian education.

In April, the Australian government finally published its airy and platitudinous report and review of the country’s schools. Popularly known as ‘Gonski 2.0’ after David Gonski, the businessman who chaired the review panel and who had chaired a previous review of school funding, it provided little evidence to support its proposals, despite evidence being a key requirement in the terms of reference. The report states that Australia must ditch its ‘industrial model’ of school education, the sort of cliché you would expect to hear in the most derivative education conference speech. Instead, each young person must “emerge from schooling as a creative, connected, and engaged learner with a growth mindset” (see here for a double meta-analyses of growth mindset interventions which shows that they have virtually no effect). The details of how to achieve this are vague, but the panel is clear on one key point: rigid, age-based curriculum content must be blown apart in favor of progressing students individually through a set of skills such as literacy, numeracy, critical thinking, and self-management.

Despite its managerial and bureaucratic presentation, and despite the instrumental appeal to an uncertain future jobs market, the Gonski 2.0 review’s recommendations are the latest incarnation of a century or more of evidence-free approaches to teaching and learning; an enduring tradition that is central to any understanding of the forces shaping education today. Given the historic failure of this tradition—sometimes described as ‘progressive education’—we can predict with near certainty the likely effect of these recommendations: they will accelerate the decline of Australia’s schools.

The Gonski panel is the chorus and we are the audience. The play is the ongoing tragedy of Australian education.

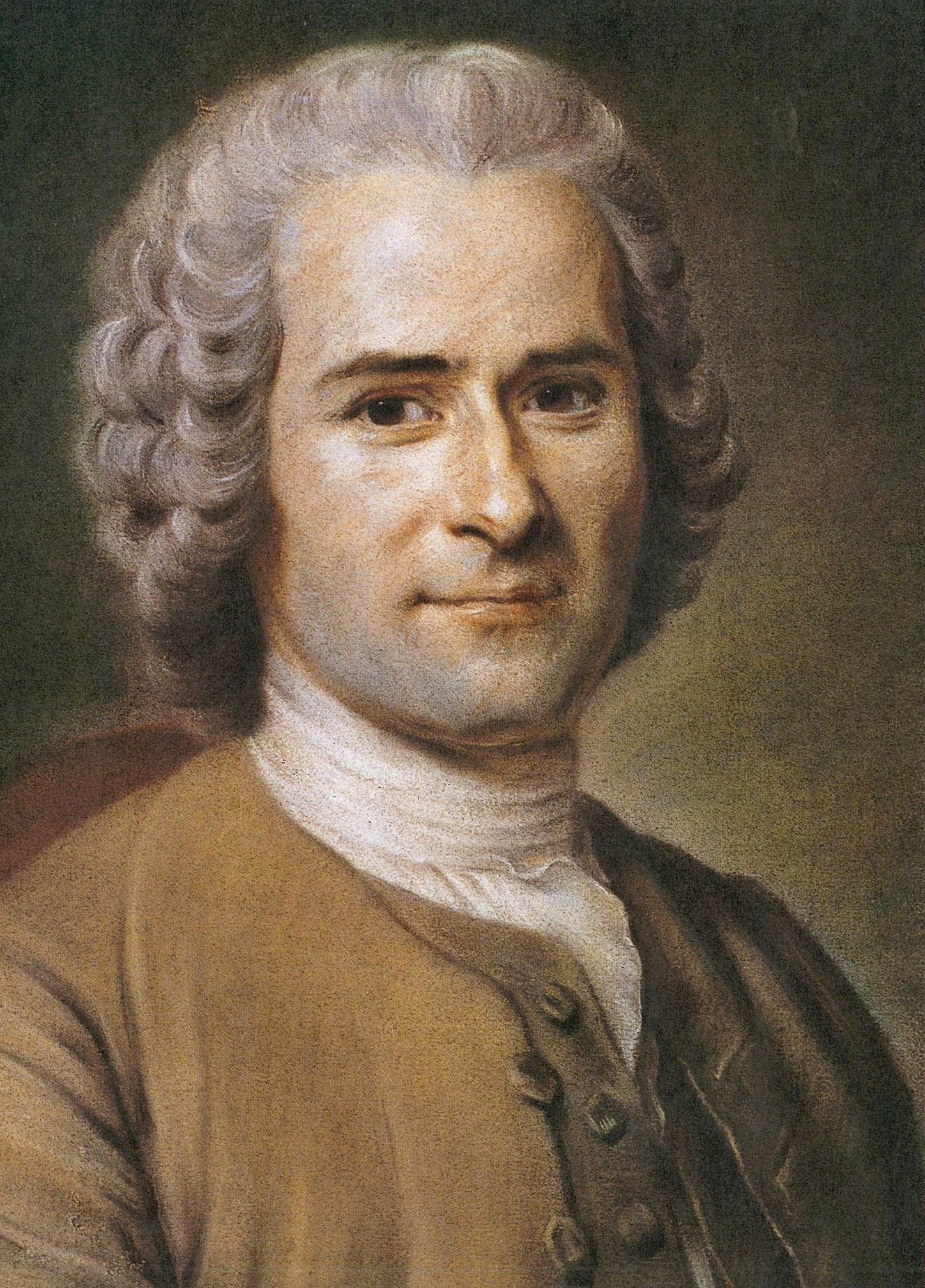

The historical figure with the greatest single influence on today’s education academics and bureaucrats is probably Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whether they have read his work or not. Rousseau sits at the confluence of two great cultural rivers, the point where the Enlightenment flows into the Romantic period. In his novel Emile, Rousseau describes the education of its eponymous hero. Under the guidance of a private tutor, Jean-Jacques, Emile is to be formed into a ‘natural man.’ From the Enlightenment, Rousseau draws on empiricism and argues that Emile should primarily learn through personal experimentation and experience. Anticipating the Romantic period, Rousseau seeks a form of education that preserves the innate natural goodness of children before they are corrupted by contact with the world.

Rousseau is a complex figure. He gave up his own children to a home for foundlings and this makes his musings on education seem incongruous, particularly given that Emile’s tutor shares Rousseau’s name. And an analysis of the role of the tutor in the novel throws up something of a paradox. He avoids any form of expository teaching, instead following Emile’s natural interests and inclinations. Yet he constantly manipulates those interests by interfering in Emile’s environment, carefully stage-managing the ‘natural’ experiences which Emile learns from. Rousseau wants Emile’s inclinations and enthusiasms to dictate everything he learns because they are untainted by toxic civilization, and yet his tutor, an adult corrupted by society, feels he has a right to shape those ‘natural’ proclivities at every turn.

Toward the end of the 19th and early 20th century, progressive educators sought a new, modern form of education. In reacting against dusty school halls characterized by recitation and harsh discipline, they invoked Rousseau’s vision of the natural goodness of children and the value of learning through personal experience rather than via a didactic authority figure. This was to be a modern, ‘scientific’ form of education that viewed each child as a unique individual. Through its enigmatic representative, the pragmatic philosopher John Dewey, who later disavowed some of the excesses of progressive education, a movement took root in the teacher education colleges of America. This movement radiated across the world, drawing on other, similar educational philosophies as it spread. Initially, private schools were the subjects of progressive experimentation before it was enacted to varying degrees in state education systems.

It is important to note that the alignment of progressive education with progressive politics is loose at best, with anyone espousing a more modern and funky education system, from whatever part of the political spectrum, tending to draw upon its reservoir of ideas. In 1930s Italy, it was Mussolini’s education minister who pursued progressive education, while Antonio Gramsci, a Marxist, offered a traditionalist critique. Progressive education’s focus on the individual and the insistence that some children are simply not cut-out for academic learning plays well to sections of the political Right. In contrast, the rise of postmodernism since the 1960s and its capture of some parts of the political Left has found a parallel in the progressive argument against a knowledge-rich curriculum. Whose knowledge should be taught? Is it the knowledge of dead, white, European males? If all facts are socially constructed, why privilege one body of knowledge over another? Educational progressivism, with its focus only on content that is interesting and relevant to the individual child—and taking into account the ‘oppressed’ groups that child belongs to—seems like a natural outcrop of the postmodernist critique of traditional subject knowledge.

While progressive educators of the early 20th century stressed that learning knowledge, which they always reduced to the rote learning of facts, is boring and unnatural, early 21st century postmodernists challenge the validity of traditional knowledge by viewing it as an expression of white, male, heteronormative oppression. Both currents amplify and reinforce the other, with the upshot that it is almost impossible for the Australian educational establishment to think its way out of this bind.

When you treat knowledge, the very substance of education, with suspicion, what is left? What should be taught in schools, if not knowledge?

The popular, if deeply flawed, answer to this dilemma is to re-brand academic subjects as ‘skills.’ Reading and writing—and, more recently, evaluating the veracity of internet sources—has become the skill of ‘literacy.’ Mathematics, with a little more justification, becomes the skill of ‘numeracy.’ Layered on top of this are supposedly general purpose skills such as ‘problem-solving’ and ‘critical thinking.’ Content is thought to be interchangeable in the development of all these skills—it’s not what you learn but how you learn that’s important. No need to cover the basics or the boring stuff. Out goes Shakespeare and in comes something more interesting and relevant. It is all the same. It is all going to develop a child’s literacy skills.

Gonski 2.0 follows this model closely when it suggests the creation of ‘learning progressions.’ The idea is that a panel of experts will meet and draft a set of levels through which they think learning should progress within a particular domain. Teachers will then apply multiple criteria and assess whether each student has achieved one of these levels. There is some value in trying to map out the course of learning, especially when planning a sequence of lessons, but there is little value in decontextualized pathways of this kind. When trying to apply these criteria, and demonstrate that their students are making progress, teachers will have an incentive to rely on simpler content. For instance, a teacher will find it much easier to demonstrate that a child can “support ideas with some detail and elaboration” by asking him or her to write about a family trip to the zoo than about Australia’s system of compulsory voting. In general, such systems encourage teachers to dial down the intellectual challenge and, instead, focus on form-filling nonsense.

Progressive educationalists argue that developing skills such as critical thinking and problem-solving involves students learning from personal experience, as advocated by Rousseau. According to this theory, students should conduct their own investigations and organize their own research projects in contrast to the supposedly old-fashioned approach where teachers stand at the front of the class and explain things to them.

Unfortunately, there is no evidence that critical thinking and problem-solving can be taught in this way. As Daniel Willingham, a professor of psychology at the University of Virginia, explains, you need to master a subject before being able to think critically about it. Young children can think critically about subjects they know a great deal about, whereas trained scientists can fail to think critically in areas where they lack knowledge. That is, these skills are domain specific and cannot be taught as stand-alone abilities, divorced from subject knowledge. There is pretty much nothing that you can learn by solving the problem of a blocked toilet that you can apply to the problem of solving a set of simultaneous equations. Instead, you need knowledge relevant to the specific kind of problem you are trying to solve.

Another difficulty with the progressive approach is that it is at odds with cognitive scientists’ understanding of how memory works. Working memory—that is, what we are focussing on at the moment—is severely limited. As early as the 1950s, the psychologist George Miller pointed to evidence that we can only hold about seven items in our working memory at any one time. We now think the number is likely to be even smaller. This is not a problem when it comes to learning to talk. Humans have been talking, or trying to talk, for hundreds of thousands of years and so evolution has had time to fashion ‘modules’ or ‘apps’ that allow us to effortlessly take in the information we need. However, reading and writing are only a few thousand years old and for much of that time they have been the preserve of a tiny elite. Evolution cannot lend a hand and so, in order to learn to read and write, or learn any other academic discipline, we have to process knowledge in our working memory before it can be transferred to our long-term memory.

In contrast to working memory, there appears to be no practical limit to what we can store in our long-term memory. However, it would be a mistake to think of the long-term memory as a bottomless filing cabinet. It is more like a set of webs connecting related ideas. Knowledge can fade if we fail to make use of it, or it may still be there in the long-term memory but hard to retrieve. This suggests the value of regularly recalling knowledge that we want to be available for us to use, something that has been confirmed by research.

Long-term memory can help overcome the limitations of working memory. To give a simple example, if you just know that seven times eight is 56, you don’t have to use working memory resources to figure it out and you can concentrate on some other aspect of a math problem. Perhaps more subtly, a fully established concept such as ‘democracy’ can consist of scores of connected ideas and take years to develop. Yet once you have this concept available in your long-term memory you can effortlessly bring it to bear on problems without running up against the usual constraints.

This understanding of the mind suggests that novices need to learn new concepts in small, discrete steps. They need to be guided to pay attention to just a few features at a time. The role of a teacher is, therefore, to fully present and explain new concepts in bite-size chunks, at least in the earlier stages of learning, and to give students plenty of practice at recalling these concepts via frequent testing. Once learning progresses, ideas can start to be integrated into more complex wholes.

However, if you take Rousseau’s advice and present novices with complex or real-world problems to solve, or areas to investigate, their working memories will become overloaded. Even if they manage to solve a particular problem, they are likely to learn little from the process because they will have no cognitive resources left over for learning.

This conclusion is supported by research into effective teaching. As early as the 1950s and 1960s, academics began conducting process-product research. They would sit in the classrooms of different teachers and observe and document what those teachers did—the ‘process.’ They would then look at test score gains for those teachers—the ‘product.’ The evidence was clear: effective teachers presented concepts and procedures in small chunks, fully explaining them, and they asked lots of questions of students, from informal verbal questions to frequent reviews and testing.

When we reflect on the role of long-term memory, it is clear that the content of the curriculum is extremely important. For example, if you want students to think analytically about an aspect of democracy then you need to build up their knowledge of the concept in long-term memory. The same is true if you want them to read and understand all but the most basic texts about democracy. There is no shortcut to doing this without the right knowledge. That is because knowledge is what you think with. It is, therefore, a duty of schools and education policymakers to ensure that the curriculum contains content that is rich and powerful; knowledge that allows access to the kinds of thinking that well-educated adults are able to perform. There are clearly vigorous, democratic debates to be had about which knowledge we should teach, but we should have these debates rather than avoid them by pretending knowledge isn’t important.

The tragedy of Gonski 2.0 is that it does nothing to advance this debate but instead proposes that Australian schools should embrace ideas that were current in England about 10 years ago. Where Gonski 2.0 emphasizes the development of general capabilities, the English national curriculum used to promote Personal Learning and Thinking Skills. Where Gonski 2.0 suggests an intricate set of learning progressions, England had a similar system that also embraced ‘levels.’ This approach was abandoned, partly because it saddled teachers with far too much busy work as they collected all the data required to show that children were making good progress, as well as mounting evidence that it was ineffective.

In recent years, England is one of the few countries that has sought to bolster the knowledge taught in its national curriculum and turned away from the progressive education orthodoxy. The early signs are that this new approach has reversed years of decline, particularly among 4-11-year-olds. How has England managed to break these shackles while Australia draws them tighter?

One answer is the role of Michael Gove as Secretary of State for Education from 2010–14. An outspoken Conservative, Gove was, and remains, a hate figure for many in the education sector. But whatever you think of him, Gove is one of the few politicians to master the education brief. He understood the argument about the vital role of knowledge in a way that no Australian politician has. It also helps that another of England’s education ministers, Nick Gibb (still in post) is an evangelist for the knowledge-based approach.

In parallel with Gove’s rise as Education Secretary, and continuing after his fall, there has been a burgeoning professionalism among teachers in England. Social media has enabled them to bypass the traditional gatekeepers of education research and talk to each other via blogs and through online forums such as Twitter. When I first started teaching, I thought it was an established scientific fact that children learn better by finding things out for themselves. It was only when I began to read the research for myself that I realised this was untrue. The internet has provided the means for this information to reach teachers more readily.

If you are in London on September 8, you might happen on a group of teachers on their way to an event. This event will not have been organized by their schools or by anyone in the education establishment. Instead, the “researchED National Conference” has been organized by Tom Bennett, a teacher who gave up his job after the overwhelming success of the first few researchED events. Promoted through social media, researchED gives a platform to teachers and academics to discuss the use of educational research in the classroom. Along with other similar events, it is evidence of a welcome trend—a profession that is taking control of its own destiny.

Although researchED is now an international phenomenon, having visited Australia three times, there is not yet an Australian equivalent. This may be geographical—if you organize a one-day event in Birmingham then a large swathe of English teachers will be able to attend, but an event in Sydney isn’t as easy to get to for teachers from Adelaide.

Nevertheless, there are encouraging signs. Gonski 2.0 has been given a deservedly rough ride in the press, with some teachers expressing their disappointment. There are signs that educators are at last beginning to realize there are counter-arguments to the established dogmas. This is long overdue, given that John Sweller, a world expert in how working memory and long-term memory affect learning, has been hiding in plain sight at the University of New South Wales all this time.

Ultimately, it is pointless waiting for education academics or businesspeople co-opted by the government to suggest practical ways forward for Australian education. The former are largely uninterested, preferring to defend their own discredited theories, whereas there is no reason to think the latter will be able to clear away the unhelpful ideological baggage, as Gonski 2.0 has demonstrated. Instead, it is time for Australian teachers to take control of the agenda. It is time for Australian teachers to talk directly to each other and to researchers. It is time for Australian teachers to organise themselves into a profession that owns its own knowledge.

A lack of knowledge is the problem. It is the lack of scientifically-informed, evidence-based expertise that enables the education tragedy to unfold in one country after another, in one time period after another. Developing the knowledge of teachers—and trusting to their expertise—is our best hope of breaking out of this vicious circle.