colonialism

'If I Want to Hold Seminars on the Topic of Empire, I Will Do So Privately': An Interview with Nigel Biggar

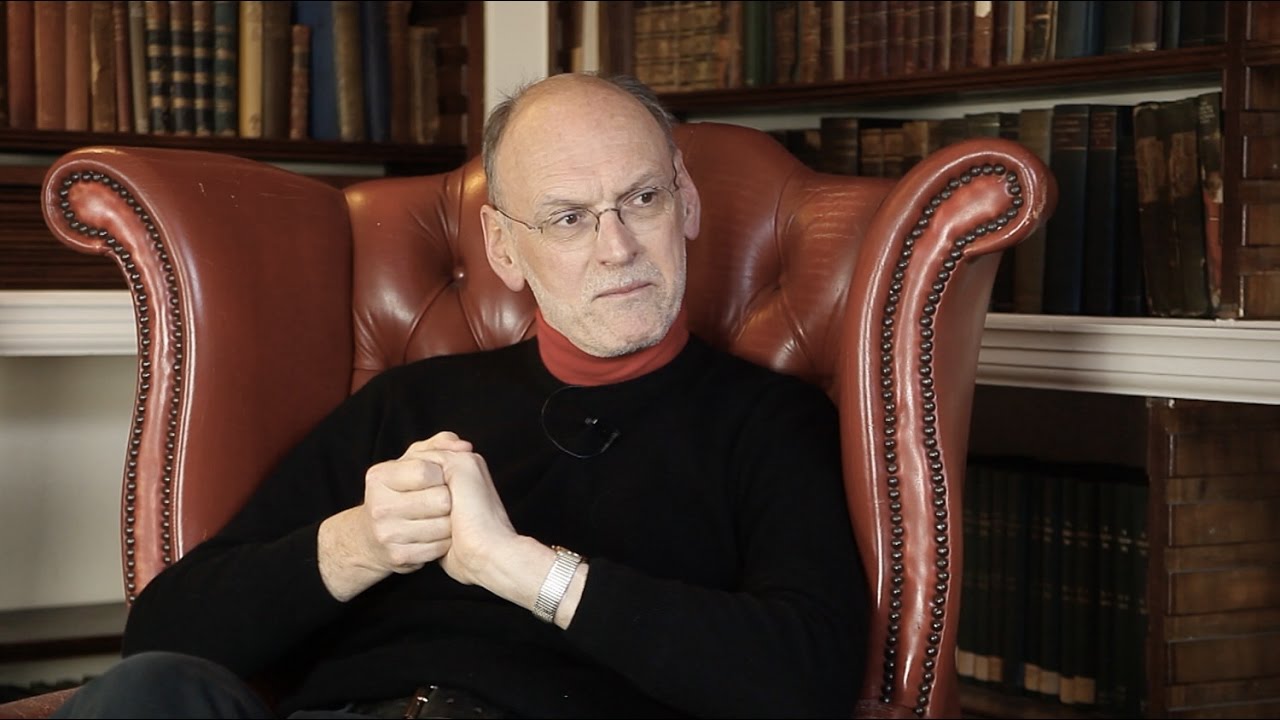

Somewhat similarly, at Oxford, professor Nigel Biggar was targeted immediately after his project “Ethics and Empire” was launched.

“Crete, unfortunately, made more history than it can consume locally,” Saki once wrote. The same can be said about the University of Oxford. Perhaps England’s last struggling bastion of meritocracy and intellectual hierarchy, Oxford is lately under relentless attack from equity activists trying to install affirmative action, and historical revisionists and ideologues trying to wreck Western canon in the name of ‘decolonization.’

I was invited at Christ Church College to take part in a private and secret colloquium and roundtable (a lot of the participants didn’t want their name and photos out because their careers might be jeopardized), on colonialism and imperialism. The chief speaker was Portland State professor Bruce Gilley, whose article argued that colonialism was much more nuanced than presented in modern Marxist and post-colonial discourses, and was then predictably retracted by Third World Quarterly, after protests by social justice activists. Somewhat similarly, at Oxford, professor Nigel Biggar was targeted immediately after his project “Ethics and Empire” was launched.

The colloquium itself went smoothly without protests perhaps because it was a secret, with no social media promotion. I had an opportunity to ask professor Biggar why he chose to organize the colloquium in secret and if this is the future of academia. What follows is an edited transcript of our discussion.

Sumantra Maitra: How severe was the backlash you faced after deciding on your project and how did that start? Is it over or still going? Do you feel targeted?

Professor Nigel Biggar: In late November 2017 I published an article in which I argued that the British should feel both guilt and pride over their imperial past, and a week or so later in early December I mounted on the website of the McDonald Centre for Theology, Ethics, and Public Life a description of the ‘Ethics and Empire’ project that had been launched the previous July.

Oxford university defended Nigel Biggar's column about British colonialism https://t.co/Z6dvQWbvI6

— The Times and The Sunday Times (@thetimes) December 15, 2017

Within days the first of three online denunciations were published, one of them signed by 58 more or less Oxford postcolonialist colleagues, some historians, many not. Shortly before the Oxford denunciation was published, my main historian-collaborator in the project suddenly resigned (as, later, did another historian). Very oddly, not one of the denunciations attacked him, even though he is an eminent historian of empire, global as well as British, and even though the project was conceived with him from the beginning. All the criticism was directed at me. Some of the criticism involved reasons (albeit poor and confused ones), much of it (especially online) consisted of ad hominem attacks and lazy and promiscuous accusations of ‘racism’ and ‘white supremacism.’

The British empire was constitituvely racist. Its great theorists & chroniclers at the time had the virtue of never denying that it was fundamentally premised on Anglo-Saxon racial superiority. Ergo, today's apologist--including Nigel Biggar--are racists. But dishonest ones.

— Priyamvada Gopal © (@PriyamvadaGopal) December 26, 2017

In retrospect, there was more than a hint of panic about it, as if the critics were terrified of being found out. Since I have learned to block anyone on Twitter, who shows herself unwilling to engage in the give-and-take of reasoning, and inclined instead to repeat prejudices and indulge in personal abuse, I am blissfully unaware of how much my project continues to excite and obsess online colleagues. (I should add that we have kept an almost complete record of the row, and its international press coverage, on the website of the McDonald Centre in 3-4 ‘News’ items.)

SM: How’s the situation in Oxford on free inquiry, and the study of history as a discipline? How’s the free speech situation, and what could be done in your opinion?

NB: The university authorities were swift to support me and to affirm my academic competence to run the ‘Ethics and Empire’ project; and the history faculty and the humanities division have so far resisted attempts to interfere. That’s all good. On the other hand, the alienating manner of online denunciation, together with the arrogant and contemptuous tone of much of the criticism, the personal attacks, and the abusive incivility of some colleagues have destroyed trust. It is now highly unlikely that I will choose to involve any of the signatories in the project, since I have no confidence in their readiness to engage in the reciprocal and forbearing exchange of reasons.

What is more, if I want to hold lectures or seminars on the topic of empire, I will do so privately, since I cannot be sure that my critics will behave civilly. On one occasion recently, I held a day-conference to discuss Bruce Gilley’s controversial article, “The Case for Colonialism,” and found myself having to use pseudonyms to hide the identities of some participants. One young scholar only attended on condition that his name nowhere appear on print, nor his face on any photograph, lest his senior colleagues find out and kill his career. What this shows is that the legal right to freedom of speech is not enough. What’s also needed are colleagues who are willing to conduct themselves according to informal norms of civility and responsible, rational exchange. Clearly some colleagues are not so willing. So the question is, will middle-managers in universities—faculty and college heads—do anything to uphold norms of civility against colleagues who trample over them, or will they abrogate their civic responsibility and off-load it onto the courts?

SM: What next for the project? How to go forward from there?

NB: The good news is that the overall effect of the row over ‘Ethics and Empire’ has been to strengthen it. I now know, which I didn’t before, that the UK press (and presumably their readership) is overwhelmingly supportive of what I am trying to do. I also now know that there are plenty of people of “non-white skin and bearing non-Anglosaxon surnames,” the children or the grandchildren of the subjects of British Empire, who agree more with me than with my critics. Moreover, the two historians who resigned have been replaced by three others. Most important, however, is this: that I have faced my critics and written two responses to them.

What I’ve discovered, as I’ve stated elsewhere, is that their objections are, by turns, opaque, confusing, confused, ignorant, tendentious, and much preferring to attack distortions of what I say than what I actually say. That last point is significant and encouraging, because the only reason anyone can have for setting up a straw man to knock down is that he really can’t find an effective way of attacking the real target. These emperors are very largely naked.

Nigel Biggar is regius professor of moral and pastoral theology, and director of the McDonald Centre for Theology, Ethics, & Public Life at the University of Oxford