Art and Culture

A History of the Struggle for Gay Equality: Civil Rights or Counterculture Movement?

While the achievements of the gay rights movement are commendable, we should be wary of queer separatist activism.

The history of the gay rights movement in the United States is fascinating, and its progress raises an interesting question about the nature of its activism. Has the struggle for gay equality been primarily a universalist drive for equity and civil rights, with the inter-related goals of individual liberty, respect, and freedom from persecution? Or is it a social justice movement driven by a countercultural constituency intent on separating itself from mainstream culture? The answer is that the gay rights movement in the United States is a complicated combination of both perspectives.

To date, the successes of the gay rights movement in the United States have been laudable. The repeal of laws that criminalized homosexual sex was a significant gain. As a consequence, gay people can now live openly and are free to marry. It is true that elements of anti-gay prejudice linger, mainly among the ranks of the religious and the socially conservative. It also remains the case that only a patchwork of laws exist across the 50 states prohibiting discrimination in employment on the grounds of sexual orientation. However, I think these are the least of the worries for the gay rights movement in the United States. While both civil rights and social justice perspectives have contributed to the success of the gay rights movement, what most concerns me about the current state of the gay rights movement in the United States is the influence of a decidedly countercultural constituency of U.S. society.

The current gay rights movement in the United States began in earnest in 1950 with the founding of the Mattachine Society. Harry Hay, a counterculture figure and a member of the Communist Party USA, founded the Mattachine Society with a group of like-minded gay men, Konrad Stevens, Dale Jennings, Rudi Gernreich, Stan Witt, Bob Hull, Chuck Rowland and Paul Bernard. Together they set about agitating for the following stated goals:

- “Unify homosexuals isolated from their own kind.”

- “Educate homosexuals and heterosexuals toward an ethical homosexual culture paralleling the cultures of the Negro, Mexican, and Jewish peoples.”

- “Lead the more socially conscious homosexual to provide leadership to the whole mass of social variants.”

- “Assist gays who are victimized daily as a result of oppression.”

The third point in this list stands out. What is meant by the “whole mass of social variants” is unclear, but the phrase presumably encompasses cross-dressers, transsexuals, and polyamorists. The Mattachine Society further asserted that homosexual oppression was socially determined and held that strict definitions of gender roles led men and women to uncritically accept social roles that likened “male, masculine, man only with husband and father” and “female, feminine, women only with wife and mother.” As Jeffrey Excoffier explained in his 1998 book American Homo: Community and Perversity, the Mattachine Society saw gay men and women as the target of a “language and culture that did not admit the existence of a homosexual minority.”

The Mattachine Society and its Communist leaders successfully drew public attention to the plight of gay people in mid-twentieth century American society. Unfortunately, their consciousness-raising efforts coincided with the Second Red Scare (1947-1957) more commonly known as the McCarthy era, a period of considerable hysteria about the threat of Communist subversion. As Craig Kaczorowski has observed, the radical activism of the Mattachine Society did not pass unnoticed. In 1953, a columnist for a Los Angeles newspaper referred to the Mattachine society as “a ‘strange new pressure group’ of ‘sexual deviants’ and ‘security risks’ who were banding together to wield ‘tremendous political power.'” Linking gay rights with the American Communist Party during the Second Red Scare was not especially conducive to winning hearts and minds, and so the Communist founders of the Mattachine Society stepped down in 1953. The Mattachine Society continued its advocacy at a national level until 1961 and, at the very least, succeeded in generating interest among gay people in the cause of civil rights.

Following the decline of the Mattachine Society, new groups emerged, such as the Society for Individual Rights (SIR), founded in San Francisco in 1964, and the North American Conference of Homophile Organizations (NACHO), founded in 1968. Both the SIR and NACHO advocated for the civil rights of gay and lesbian individuals on constitutional grounds using the democratic process. According to a summary provided by the Online Archive of California:

SIR’s goals included public affirmation of gay and lesbian identity, elimination of victimless crime laws, providing a range of social services (including legal aid) to “gays in difficulties,” and promoting a sense of a gay and lesbian community. […] Taking a cue from the burgeoning civil rights movement, SIR demanded equal rights and decried government-sanctioned discrimination.

NACHO, meanwhile, formulated a Homosexual Bill of Rights at its 1968 meeting, detailed as follows:

- Private consensual sex between persons over the age of consent shall not be an offense.

- Solicitation for any sexual acts shall not be an offense except upon the filing of a complaint by the aggrieved party, not a police officer or agent.

- A person’s sexual orientation or practice shall not be a factor in the granting or renewing of federal security clearances or visas, or in the granting of citizenship.

- Service in and discharge from the Armed Forces and eligibility for veteran’s benefits shall be without reference to homosexuality.

- A person’s sexual orientation or practice shall not affect his eligibility for employment with federal, state, or local governments, or private employers.

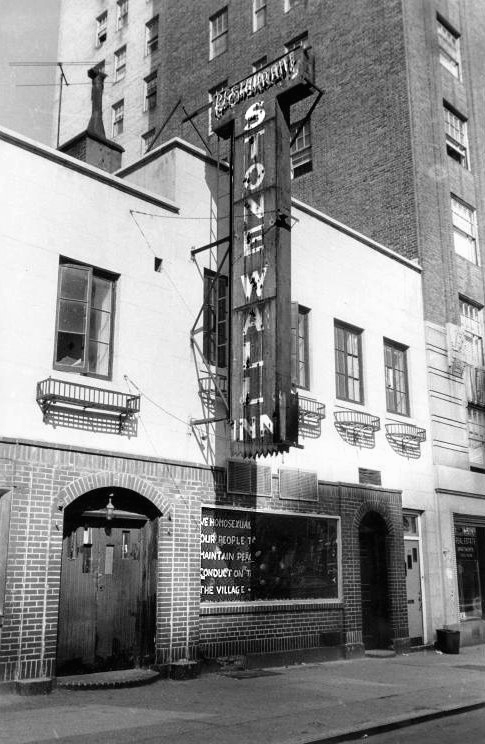

Following the Stonewall riots in Greenwich Village that began on June 28, 1969 (a defining moment in the gay rights movement in the United States), activists founded the Gay Liberation Front and the Gay Activists Alliance. The Gay Liberation Front rejected the goals and strategy of the Society for Individual Rights and NACHO, declaring instead that:

We are a revolutionary group of men and women formed with the realization that complete sexual liberation for all people cannot come about unless existing social institutions are abolished. We reject society’s attempt to impose sexual roles and definitions of our nature.

The Gay Activists Alliance, on the other hand, continued the more patient work of the Society for Individual Rights and NACHO. As Linda Rapp has noted:

A central tenet of the GAA was that they would devote their activities solely and specifically to gay and lesbian rights. Furthermore, they would work within the political system, seeking to abolish discriminatory sex laws, promoting gay and lesbian civil rights, and challenging politicians and candidates to state their views on gay rights issues.

The Gay Liberation Front folded in 1973, whereas the Gay Activists Alliance continued operations until 1981.

Countercultural thinking in gay rights activism resurfaced in 1990 with the emergence of Queer theory, an ideological position that repackaged the goals defined by Harry Hay and the Mattachine Society in 1950 for the postmodern age. In brief, as Renee Janiak notes in a summary:

To be queer means, “fighting about social injustice issues all the time, due to the structure of sexual order that is still deeply embedded in society” (Warner: 1993). Queer people are not assigned into a specific group or category, which would be comparable with any other type of grouping such as “class” or “race” (Warner: 1993). Queer people have made a change with how they identify themselves, they went from “gay” to “queer.” The self- identification change is due to that fact that “queer” represents the struggle of not wanting to fit into the systems of being “normal.” Queer theory has allowed for new political gender identities (Butler: 1990).

In the new activist lexicon, ‘Queer’ or ‘LGBTQI’ replaced ‘gay’ and ‘lesbian’ as preferred terms of self-identification, a change intended to signify that gay and lesbian people did not want to fit into “existing social institutions,” now redescribed as ‘heteronormativity.’ Queer activists strive—just as Harry Hay and the Mattachine Society did in 1950—to organize a community composed of “the more socially conscious” gays and lesbians “to provide leadership to the whole mass of social variants” in developing a parallel “queer culture.”

Queer theory gained increased mainstream attention in 2016 when Noah Michelson renamed the Huffington Post‘s ‘Gay Voices’ section ‘Queer Voices.’ Michelson justified the change on the grounds that this “word is the most inclusive and empowering one available to us to speak to and about the community.” The thinking here is that people who are gay, lesbian, bisexual, transsexual, etc. are part of a ‘community’ and they share a collective group identity. Following this train of thought, Michelson asserted that “‘queer’ functions as an umbrella term that includes not only the lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgender people of ‘LGBT,’ but also those whose identities fall in between, outside of or stretch beyond those categories, including genderqueer people, intersex people, asexual people, pansexual people, polyamorous people and those questioning their sexuality or gender, to name just a few.”

Michelson and other likeminded activists are obviously free to promote this narrative and to pursue their separatist goals but, in reality, ‘gay’ is a demographic not a coherent community. For many (if not most) gay people in the United States, the gay rights movement remains a civil rights concern, driven by the efforts of gay and lesbian individuals using the democratic process and pressing their case on constitutional grounds. It has been this approach, and not the remote theorising of cloistered academics, that resulted in two of the most recent and pivotal victories in the push for the gay equality in the United States have been Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003) and Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. (2015).

Established in 1973, Lambda Legal states that its “mission is to achieve full recognition of the civil rights of lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, transgender people and everyone living with HIV through impact litigation, education and public policy work.” Lambda Legal took on Lawrence v. Texas and successfully shepherded it through the lower courts all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States. The Supreme Court voted to repeal sodomy laws in a 6-3 decision. Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing for the majority, ruled that the state could not single out gay people for harassment and discriminatory treatment on the grounds of moral disapproval. “When sexuality,” he wrote, “finds overt expression in intimate conduct with another person, the conduct can be but one element in a personal bond that is more enduring. The liberty protected by the Constitution allows homosexual persons the right to make this choice.” He observed that reducing same-sex couples to sex partners demeans those relationships “just as it would demean a married couple were it to be said marriage is simply about the right to have sexual intercourse.”

Obergefell v. Hodges finally lifted the ban on same-sex marriage in the United States in a split decision (5-4) handed down by the Supreme Court on June 26, 2015. The background to this ruling involved court challenges mounted by multiple gay and lesbian couples in four states: Ohio, Michigan, Kentucky, and Tennessee. The Oyez Project noted in its summary of Obergefell v. Hodges:

The plaintiffs in each case argued that the states’ statutes violated the Equal Protection Clause and Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and one group of plaintiffs also brought claims under the Civil Rights Act. In all the cases, the trial court found in favor of the plaintiffs. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reversed and held that the states’ bans on same-sex marriage and refusal to recognize marriages performed in other states did not violate the couples’ Fourteenth Amendment rights to equal protection and due process.

Writing for the majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy stated:

[W]hile Lawrence confirmed a dimension of freedom that allows individuals to engage in intimate association without criminal liability, it does not follow that freedom stops there. Outlaw to outcast may be a step forward, but it does not achieve the full promise of liberty.

He went on to observe that, “It is of no moment whether advocates of same-sex marriage now enjoy or lack momentum in the democratic process. The issue before the Court here is the legal question whether the Constitution protects the right of same-sex couples to marry.” Constitutionality was the basis for the Supreme Court’s decision to lift the interdiction on same-sex marriage in the United States. As Justice Kennedy explained:

Especially against a long history of disapproval of their relationships, this denial to same-sex couples of the right to marry works a grave and continuing harm. The imposition of this disability on gays and lesbians serves to disrespect and subordinate them. And the Equal Protection Clause, like the Due Process Clause, prohibits this unjustified infringement of the fundamental right to marry.

Thus, the successes of the gay rights movement as a civil rights movement in the United States rest firmly with gay and lesbian individuals who have exercised their right to employ the democratic process. The successes of the gay rights movement and the strategy behind them are grounded in the principles of liberalism as defined by John Stuart Mill. In On Liberty, Mill advanced the proposition that:

The only freedom which deserves the name is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, we shouldn’t attempt to deprive others of theirs, or impede their efforts to obtain it. Each is the guardian of his own health, whether bodily, or mental or spiritual. Mankind gains by suffering each other to live as seems good to themselves, than by compelling each to live as seems good to the rest.

The goal of the gay rights movement is full civil rights for gay and lesbian people as individuals so that they may participate freely and openly in American society; where their sexual orientation is of no more significance than that of their heterosexual neighbours. Gay people are not part of a community, least of all a ‘queer community.’ The notion that gay people ought to refer to themselves as such and consider themselves part of a wider class of people that includes genderqueer people, intersex people, asexual people, pansexual people, polyamorous people and those questioning their sexuality or gender only creates confusion. Gay people are individuals with their own priorities as they make their way through life, who only want to be treated like anyone else. Sexual orientation—be it homosexual or heterosexual—is incidental, not a defining characteristic.

Given this reality, it is proper that gay and lesbian civil rights advocates in the United States acknowledge the historical contribution to their movement made by the countercultural constituency represented by Harry Hay and the Mattachine Society. But they should also be wary of the current countercultural interest in Queer separatist activism, as their efforts to build a parallel ‘queer’ culture only impedes the push for full civil rights for gays and lesbians in the United States. The fact that being gay in American society is no longer stigmatized is one of the achievements of the gay rights movement in the United States. This is something Queer theorists should appreciate and celebrate for its own sake.