Top Stories

Radical Moderate: The Struggle for Martin Luther King's Legacy

If activists are embarrassed by constitutional norms, religious devotion, and American virtues, then what are the values around which a progressive movement can hope to organise?

As matters of race continue to grip the American consciousness, there have been commendable efforts to clarify and correct the historical record on slavery, the Civil War, Robert E. Lee, Confederate statues, and the complicated legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King. Activists and liberal commentators claim that Dr. King’s legacy has been whitewashed by conservatives and white society. Central to this argument is the use of his more radical works to rebut the mainstream’s identification with King and the reassuring tenor of his “I Have A Dream” speech.

King did indeed hold fervent social and economic views of which many Americans are unaware. But recent attempts to reclaim King as an identity-driven radical rather than a values-driven one rely upon the same selectivity they seek to correct. They ignore the centrality of the American gospel to King’s message, and overstate King’s most leftwing impulses so that he might serve as a precedent for modern activism’s divergent separatist ethos. But would a white supremacist nation really lionize such a fiercely empowered black man? One reason King, of all activists, stands firm on the National Mall today is because of his unshakeable belief—absent from the modern social justice establishment—in America’s redemptive capacity.

Assessing legacies are often attempts to seek objectivity in the subjective, especially when it comes to words like ‘radical.’ In today’s social environment, conservatives may claim that King was a radical for the prominent role his faith played in his activism within a greater secular culture. Leftists, on the other hand, have claimed that King was a radical for his socialist inclinations, his dovish foreign policy views, and his frustration with white society. History has certainly oversimplified King, just as it has oversimplified virtually every other leading figure in history. But the further claim is that our valorization of King is dishonest because it does not pay adequate tribute to his most controversial views.

This is the crux of the overcorrection of King’s legacy. We do not honor figures nationally because of their ideology or memorable bon mots. We honor them—from Washington and Lincoln to Kennedy and Reagan—because they led with distinctly American values that transcend identity, party, and policy ideals. We honor them because, in a very literal sense, they remind us of who we are as Americans and of the genuinely novel ideas upon which America was founded.

* * *

Discussion of King’s legacy creates conflict whenever the apolitical principles of freedom, equality, justice, and independence are conscripted into supporting or opposing particular policies. Since the heirs of King’s worldview are today politically and ideologically aligned with the Democratic Party, this empowers some to argue on moral grounds that the policies King advocated are the only policies capable of realizing his vision. This mindset is making a significant contribution to the polarization of our political discourse.

Take, for example, the euphemistic pinwheel of ‘economic justice,’ or the admirable pursuit of a sustained correlation between wages and productivity. Some still argue that this can only be attained with the (democratic) socialism and the nationalization of industry for which King once advocated. King may well have believed that such a rigidly ordered system would deliver economic justice, but history indicates that sustaining it invites precipitous corruption and crippling administrative coercion. Equality would be pursued at the expense of the more fundamental ideals of liberty and justice to which King was committed and for which he fought.

King died five years before the most egregious consequences of this project were finally revealed to the world in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s seminal The Gulag Archipelago, a thoroughgoing firsthand account of the Soviet Union’s forced collectivization programs. This was a system born of resentment and the subsequent enslavement and genocide of those accused of unearned privilege. King also died over a decade before the beginning of one of the free market’s greatest achievements: the reduction of the global poverty rate, according to the World Bank, by 80 percent over the next three decades.

Nevertheless, King did offer some elaborate and valid criticisms of capitalism, particularly southern corporatism. At the conclusion of the March from Selma to Montgomery in 1965, King offered a lucid analysis of state-sanctioned segregation as a “political stratagem employed by the emerging Bourbon interests” to divide the powerful voting bloc of poor whites and blacks who had united for higher wages during the Populist Movement. Business was able to exploit workers with the help of a government that used Jim Crow to pit black and white southerners against one another. But King’s often compelling critiques of the existing economic system and the Vietnam War were hardly unusual criticisms in their time. It does King a disservice to argue that those positions and the policy recommendations he supported were his greatest contributions to the nation, let alone a unifying credo for which any figure should be honored on a national level.

First, let’s consider the ways conservatives choose to remember King. In a 2006 report for the Heritage Foundation entitled “Martin Luther King’s Conservative Legacy,” Carolyn Garris conceded that King was “no stalwart Conservative,” but that “his core beliefs, such as the power and necessity of faith-based association and self-government based on absolute truth and moral law, are profoundly conservative.” Conservatives, Garris continued, share King’s belief that the “goal of America is freedom.”

Conservatives also praise King’s early advocacy of thrift and self-help within the black community. In a 2002 essay for City Journal entitled “Where King Went Wrong,” Joel Schwartz remarked that King Sr. “personally exemplified this classically American spirit of self-improvement” and had relied on “a muscular work ethic, spartan self-discipline, and a devotion to education to propel him into the black middle class.” He writes with approval of King’s rejection of the view that jobs requiring little or no skill were not worth taking: “Whatever your life’s work is, do it well,” King said. “If it falls to your lot to be a street sweeper, sweep streets like Michelangelo painted pictures…”

By 1967, having lost faith in the capitalist system, King muted his emphasis on self-reliance yet in his final book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community, he writes that if blacks practice fiscal prudence “the Negro will be doing his share to grapple with his problem of economic deprivation.” So, it is with some disappointment that Schwartz acknowledges King’s turn toward government welfare as a means to help poor blacks in the years before he was assassinated. And, of course, there is the overeager appreciation of King’s nonviolence doctrine by conservative personalities like Sean Hannity, who disingenuously sing its praises when police killings of unarmed black men spark riots in black communities.

For many on the Left, all this is untenable. They view the conservative remembrance of King as a means of redacting the brutality he and the wider civil rights movement endured in their pursuit of equality. They see the twisting of King’s words to excuse a form of colorblind racism that defangs King of his most radical qualities. They see a heavily cropped image of King that conveniently disregards his socialist sensibilities, such as his calls for wealth redistribution, a guaranteed annual wage, and the nationalization of industries. They see conservatives appropriating King’s legacy even as they promulgate policies that the Left contends harm black Americans. They see conservative support for his doctrine of nonviolence doctrine as encouraging servility and the can-kicking of reform. And in conservative calls for unity, they hear an echo of the letter written by eight white Alabama clergymen, who agreed with King’s ends but rejected and denounced his confrontational means.

To some black Americans, this selective recognition of King’s legacy smacks of opportunism and appropriation. While a judgement about which of King’s words and deeds were the most valuable is obviously subjective, many conservatives have simply got King wrong on the facts.

* * *

In order to argue that King, were he alive today, would certainly oppose affirmative action, some conservatives have cited his “Dream” speech wherein he expresses his hope for a nation in which his four children “will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” The American historian Taylor Branch, author of a trilogy on King, has said that conservatives “want to claim they understand Dr. King better than Dr. King did.” In fact, King endorsed affirmative action in 1965, saying, “A society that has done something special against the Negro for hundreds of years must now do something special for the Negro.” Asked during a lengthy interview with Playboy magazine that same year if he thought it fair to request government programs that provide preferential treatment to blacks, King responded, “I do indeed. Can any fair-minded citizen deny that the Negro has been deprived?”

The problem is that conservatives read King’s line about character in isolation, stripped of the context provided by the rest of his writing, and understand it to be the means to the Promised Land of inter-racial harmony. Progressives understand the line as an end which can only be achieved by the means of policies like affirmative action. The equality endorsed by conservatives tends be to be equality of opportunity, not outcomes. The freedom in which progressives tend to believe is the freedom from other people’s freedoms.

Further efforts to widen the narrow conservative understanding of King’s work extend to his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” written after he had defied a court injunction on a series of coordinated marches and sit-ins that took place during the Birmingham campaign of 1963. The letter is frequently cited as a body blow to the Kumbaya perception of King and his dream, in particular King’s powerfully stated thoughts on white moderates:

I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler [sic] or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action.”

This passage expresses King’s frustration with moderates reluctant to invest in the movement’s “constructive, nonviolent tension.” Today, it is often plucked out of context by some on the Left and misused in the same way that conservatives misuse King’s line about character. While conservatives tend to distort or falsify King’s words, progressives tend to amplify King’s tribalism and discard everything else. Those who most stridently implicate individual whites in society’s ills will also use King’s words to shame anyone who does not subscribe to their remedial policy preferences or who refuses to adopt their adversarial and absolutist rhetoric. This has resulted in progressive groups like the Women’s March and small but destructive insurgencies on college campuses branding themselves as moral arbiters of politically transcendent truths when, in fact, they have just bundled a range of hardline—and arguably incongruent—progressive positions together.

Perhaps the temperature is finally cooling down. The most illiberal wing of the Left are experiencing a backlash from students who want to learn as the wider public tunes out the flagrant hypocrisy that accompanies the misuse of identity politics on the Left and the Right. Even intersectionalists are struggling to adhere to their own principles and govern a diverse coalition not unlike the republic itself. The most parochial feminists have remained silent about the Arab world’s systematic oppression of women and minorities, because they do not wish to lend support to neoconservative critiques of Islam. This is but one example of people compromising their integrity simply to put clear distance between themselves and their ideological opponents.

This is hardly an inspiring tribute to the principled and universalist truths King espoused. To the contrary, identity now subordinates principle and even minorities themselves if doing so garners extra credibility among one’s in-group online. But King explicitly applied distinctly American ideas that transcend identity and were rooted in values like salvation, human dignity, justice, and freedom. They were sometimes laced with anger, sometimes with hope, but King led with those values because they precede identity, and they are the sources—not the byproducts—of racial equality.

* * *

For every line in which King spoke about identity and victimhood, there are several more that empower or that reference Scripture, the American creed, or make clear that the aim must “never be to defeat or humiliate the white man, but to win his friendship and understanding.” That quote shouldn’t be used to airbrush King, but his due diligence in articulating that distinction lends him an integrity that is lacking in much of today’s activism. As his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” demonstrates, part of what made King a true radical was, paradoxically, his moderation. Two paragraphs after he had addressed the white moderate, King responded to being labelled ‘extreme’ by writing:

I began thinking about the fact that I stand in the middle of two opposing forces in the Negro community. One is a force of complacency, made up in part of Negroes who, as a result of long years of oppression, are so drained of self-respect and a sense of “somebodiness” that they have adjusted to segregation…The other force is one of bitterness and hatred, and it comes perilously close to advocating violence. It is expressed in the various black nationalist groups that are springing up across the nation, the largest and best known being Elijah Muhammad’s Muslim movement. Nourished by the Negro’s frustration over the continued existence of racial discrimination, this movement is made up of people who have lost faith in America, who have absolutely repudiated Christianity, and who have concluded that the white man is an incorrigible “devil.”

He continues:

I have tried to stand between these two forces. Saying that we need emulate neither the “do nothingism” of the complacent nor the hatred and despair of the black nationalist…And I am further convinced that if our white brothers dismiss as “rabble rousers” and “outside agitators” those of us who employ nonviolent direct action, and if they refuse to support our nonviolent efforts, millions of Negroes will, out of frustration and despair, seek solace and security in black nationalist ideologies—a development that would inevitably lead to a frightening racial nightmare.

This was the strategy of “the more excellent way of love and nonviolent protest” and it was a form of extremism King was, at first, reluctant to embrace. But he went on to ask:

Was not Jesus an extremist for love: “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.”

The focus on confronting specific forms of racism, on suppressing violent impulses, and not returning white prejudice is a form of discipline that can only be sustained by those daring enough to frustrate the few to advance the cause for the many. King overcame by recognizing that the path to justice is not a passive crawl or a vengeful sprint. Instead, progress is a methodical march that proves a noble end can only be achieved by an equally noble means. He understood that this meant abiding by the code of character one deserves, not the code of character to which one is ruthlessly subjected.

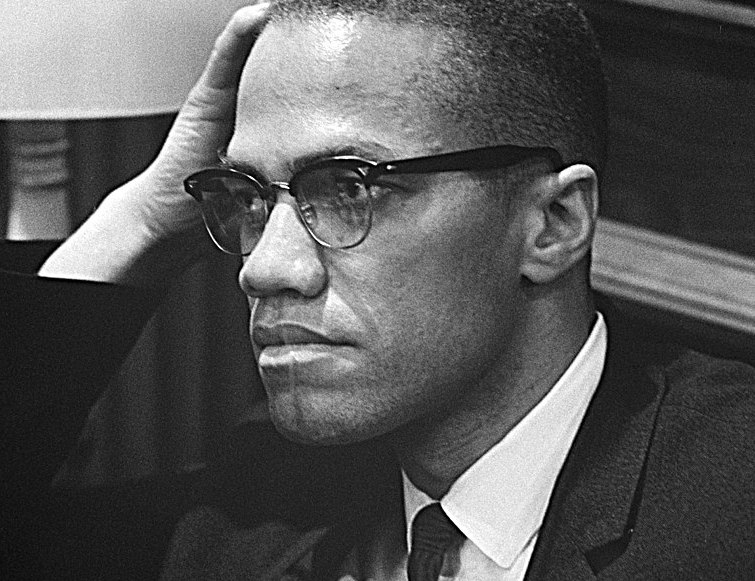

This attitude can be contrasted with that of a figure like Malcolm X who—partly due to an intellectually turbulent life that led him from black supremacist to self-creationist—did not possess the characteristics that raised an originally unassuming King to the forefront of the civil rights movement: a consistent philosophy, a commitment to nonviolence, and an unwavering belief in American redemption. His two greatest contributions are as narrow as they are deep. First, he was an inspiring orator breathing self-determination, self-worth, and as King wrote, “somebodiness” into black children and communities. Second, he articulated the seething anger black Americans felt about anti-black racism and the moderate strategies to confront it.

One might argue that King accomplished both of these things through his writings on self-reliance, his invocation of faith, and his calls for “radical changes in the structure of our society.” But, all told, Malcolm X will be remembered for bringing an intense heat to racial politics that disowned American identity and appealed to blacks’ hearts over their minds. King, on the other hand, harnessed that heat and added light. Rather than seeing the two as mutually exclusive, King saw them as interdependent and was able to justify his mind with his heart and his heart with his mind.

* * *

Two of the recurring and foundational themes in King’s sermons, speeches, and writings are those of God and American values. Over the past two decades, liberals and progressives have either been inept at discussing these things comfortably or, worse, have derided them. The 28 percent of Democratic voters who identify as non-religious have an army of secular progressive allies embedded in America’s cultural trinity—entertainment, digital news, and academia—who confirm their biases by excluding religious views and any subculture beyond the boundaries of cosmopolitanism. And, in so doing, the Left has all but ceded the iconography of the flag and the intellectual property of the Founders to their conservative opponents.

This discomfort with threading the moral fabric of America and Christian values into activism has resulted in an intellectually in-bred and sheltered generation that has constructed a like-minded digital ecosystem of exclusive inclusion. Consequently, the identity-driven Left has forfeited any inspirational unifying theme upon which to build its pursuits and broaden its support. It is not just King’s personal stature or the subtlety of modern racism that has precluded the contemporary Left from emulating his successes, it is leftists’ refusal to do the necessary work of reaffirming and invoking the philosophical commonalities that bind Americans together. They have not done this due to an obsessive-compulsive fear that it will dilute the urgency of their cause, create ambiguity about who the victims are, and place them in intolerable rhetorical proximity to their political adversaries.

These activists, particularly those from the younger generations, have not understood the origin of their own rights or the importance of wielding those rights constructively, and this is producing some troubling data. An alarming number of millennials believe in abridging the very rights that were essential to the march of racial progress. A September 2017 Brookings Institute study found that one-fifth of undergraduates say it is acceptable to use physical force against a speaker who may offend others with their viewpoints. A 2015 Pew Research poll found that 40 percent of millennials believe in limiting speech offensive to minorities. These students are agitating to restrict the rights and protections devised to protect the powerless from authority.

If activists are embarrassed by constitutional norms, religious devotion, and American virtues, then what are the resonant values around which a progressive movement can hope to organise? All that remains is the historically destructive and axiomatically divisive cause of identity. The sooner we can begin cultivating an atmosphere online and in our communities that derives strength from inclusion and commonality, instead of squalid competitions for victimhood and piety, the better. King derived his strength from love, from the God he served, from the progress he led, and from a determination to ensure that America became “true to what you said on paper.” King asked his followers to pray for the Nazi who twice socked him in the face, and it was this resistance to both hatred and passivity was emblematic of the radical moderation that set him apart.

Groups like Black Lives Matter deserve enormous credit for evolving from blocking freeways to lobbying for concrete criminal justice reforms. But any broader movement based on relentless racial contrast and the social capital earned through resentment will only nourish an addiction to instant gratification that does nothing to advance integration, justice, or freedom. Such an approach forgoes hard work for the aesthetics of rebellion. Any movement in which the rights exercised by its heroic predecessors are threatened, the religious are alienated, victimhood is fetishized and ethical consistency scorned, and where the case for justice is not made by those deprived of it, cannot and should not prevail.

Whose hearts can aimless rhetoric move if it is not tethered to anything greater than itself? Is the reluctance to stand for anything really due to paranoia that acknowledging American virtues flirts with a compromising unity? Modern activism would stand to benefit from a message as finely tuned as King’s and as timeless as the American creed. Tying American identity back to the pursuit of justice is not a ploy to inject artificial patriotism nor is it a means to dilute the emotion race stirs. Talking about America is central to the pursuit of justice because America’s birthright is justice.

* * *

The enslavement of African-Americans and the often forgotten decades of terrorism thereafter is a great sin of humanity and certainly the gravest sin of America. It is a uniquely American irony that this sin was committed by the first nation to recognize the natural rights of all people. This past, its impact on the black psyche, along with our national miseducation of it, still permeate how society perceives black Americans. But these ingenious American ideals are what set America apart from the rest of the world and allowed such a wrong to be corrected.

The American project was premised on the remarkable idea that the “unalienable rights” outlined in the Declaration of Independence and enshrined in the United States’ Constitution were not granted by government as commonly misconceived. Rather, they were pre-existing and universal rights earned at birth and—for the first time in human history—they would be formally acknowledged by a sovereign government. Unlike virtually every nation in Europe which had evolved as a consequence of history, America was uniquely, as Margaret Thatcher observed, “created by philosophy.” What originally did and should define American exceptionalism is not chest-beating nationalistic hubris but an understanding that America is a product of an arrogance that challenged—and still challenges—the standard operating procedure to which every governing force had adhered for centuries. The Founders insisted the world had it wrong: authority does not supersede individual rights. Individual rights supersede authority.

Today, our elected officials and media almost never consider how freedom imposes costs as well as benefits. Freedom isn’t self-sustaining. It breeds inherently imperfect and dynamic societies, yet that’s the daring trade-off the Founders decided to test in an attempt to break away from the tyrannical world order. The still-young idea of individual liberty disperses power rather than concentrating it behind the barrel of a gun or the stroke of an executive’s pen. If we insist on living in a free society and believe in the fruits of integration and inclusion, then we have to actively pursue them in our community.

In 1995, at the Cambridge Public Library in Massachusetts, a young black woman raised her hand to ask a question of the visiting speaker. “How do you feel about the increased push to have multi-ethnic as a political category?” The question referred to attempts by some activists to broaden the options for the “race/ethnicity” checkboxes on the Census. “I’m sympathetic to the impulse. In the end I guess I don’t agree with the strategy,” the speaker responded. “This goes back to a constant debate about ‘should we pretend we’ve got a colorblind society or, on the other hand, is everything racial, everything tribal?’… I don’t believe in those simplifications.”

13 years later, the speaker would be elected the first African-American U.S. president. This would likely mark the only time in world history that a member of a racial or ethnic group accounting for no more than 14 percent of the population of a nation—a nation that had enslaved men like him for generations—was elected leader. If we teach our history correctly, current and future generations will come to know both the brutality and enduring promise of a nation that remains true to its own novel concepts of justice, personal freedom, and human dignity. Every now and again, people like Dr. Martin Luther King come along to remind us of our American identity and challenge us to retain our high standards.

King could articulate our true moral north with impeccable eloquence, but he was also acutely aware of the inadequacy of a good heart and simply knowing right from wrong. “If in the pursuit of your destination,” Abraham Lincoln asks Thaddeus Stephens in Steven Spielberg’s 2012 film, “you plunge ahead heedless of obstacles, and achieve nothing more than to sink in a swamp…what’s the use of knowing true north?”

King stands in the colonnade of American and world history as a complicated and flawed man who nonetheless navigated a path of righteousness through chaos with a dignity that helped America to become a more perfect society able to “live with its conscience.”