Top Stories

Towards a Cognitive Theory of Politics

A Cognitive Theory of Politics can improve our understanding of contemporary political movements, such as the protests happening on college campuses.

In recent years, a consensus has been forming about how we reason and develop the opinions we defend. In his influential 2012 book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion, Jonathan Haidt argued that the first principle of moral psychology is: Intuition comes first and reasoning follows. Intuition is the reflexive gut feeling of like or dislike we experience in response to the things we see in the social world around us. In Thinking Fast and Slow, psychologist Daniel Kahneman observed that conscious reasoning requires language, the construction of an argument, and therefore time, so it can happen only after our intuition has already told us whether we approve or disapprove of something. In their book The Enigma of Reason, Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber argue that the main evolved purpose of reason is to justify our intuitions and to persuade others that our own intuitions are correct. When it comes to social issues that we care about, reason is usually a post hoc rationalization of feelings already felt and decisions already taken. In other words, it turns out that David Hume was right almost 300 years ago when he said:

Reason is, and ought only to be, the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office but to serve and obey them.

So if we really want to get to the bottom of what divides us, we should be taking a deep dive into understanding where our intuitions come from. Proper treatment of any problem requires an accurate diagnosis of its cause. The reasoning of Left and Right on things like the role of government, taxes, welfare, abortion, and gun control is to the human psyche as a fever is to an infection. If there’s to be any hope of ameliorating partisan rancor, finding common ground, and resolving issues amicably, then we must look past the symptoms and identify their real causes.

In this essay, I will propose a ‘Cognitive Theory of Politics,’ which suggests that the ideological Left and Right are best understood as psychological profiles from which political intuitions, beliefs, values, ideologies, principles, and policies follow. Ideology, and everything else, is downstream from psychology. The theory posits a new principle of moral psychology: Psychological profile comes first, intuitions follow. A Cognitive Theory of Politics can improve our understanding of contemporary political movements, such as the protests happening on college campuses, as well as past movements like the French and American revolutions. It’s not what we think that divides us; it’s how we think.

For the sake of simplicity, I’ll use the American understanding of the terms ‘liberal’ and ‘conservative’ to connote Left and Right, as explained by Jonathan Haidt in The Righteous Mind:

In the United States, the word liberal refers to progressive or left-wing politics, and I will use the word in this sense. But in Europe and elsewhere, the word liberal is truer to its original meaning—valuing liberty above all else, including in economic activities. When Europeans use the word liberal, they often mean something more like the American term libertarian, which cannot be placed easily on the left-right spectrum. Readers from outside the United States may want to swap in the words progressive or left-wing whenever I say liberal. (p xxiii)

When I graduated from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst in 1982 with a degree in mechanical engineering, I was clueless about politics. I couldn’t have told you the difference between liberals and conservatives if my life depended on it. Since I was about to become an independent adult and I wanted to take voting seriously, I thought I’d better figure it out. My engineering classes and a couple of electives I took in the business school had trained me to look for first principles—something like the prime directives in Star Trek—that could serve as guide stars for everyday decision making.

My first job after leaving college was near Washington, D.C. So, like any new arrival in the area, I spent my first few weekends exploring the museums. The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution are displayed in the National Archives, and in the gift shop there I found a copy of The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas by Carl Lotus Becker. I bought it, read it, and it whetted my appetite for more. Over the years, in between getting married, buying a house, and raising two kids, I also read:

- Decision in Philadelphia: The Constitutional Convention of 1787 by Christopher Collier and James Lincoln Collier.

- Miracle at Philadelphia: The Story of the Constitutional Convention May to September 1787 by Catherine Drinker Bowen

- The Theme is Freedom: Religion, Politics, and the American Tradition by M. Stanton Evans,

- Novus Ordo Seclorum: The Intellectual Origins of the Constitution by Forrest McDonald

- The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, by Bernard Bailyn

- A Conflict of Visions: Ideological Origins of Political Struggles by Thomas Sowell.

- The Idea of America: Reflections on the Birth of the United States, by Gordon S. Wood

- Liberty’s Blueprint: How Madison and Hamilton Wrote the Federalist Papers, Defined the Constitution, and Made Democracy Safe for the World, by Michael I. Meyerson

- Restoration: Congress, Term Limits, and the Recovery of Deliberative Democracy by George F. Will

When one reads multiple books on a subject by a variety of authors with different perspectives, common themes tend to emerge. This is known as consilience, about which Phil Theofanos recently wrote elsewhere in Quillette. Theofanos quotes E. O. Wilson’s definition:

[T]he linking of facts and fact-based theory across disciplines to create a common groundwork of explanation.

If we bear in mind that generalizations about large populations describe statistically significant trends and tendencies, averages and aggregates, overlapping bell curves and not mutually exclusive dichotomies, then one particular trend emerges quite clearly.

At bottom, ideology seems to come down to a kind of faith; a belief in one particular way of thinking as the surest path to moral truth. The Left has a greater tendency to place its faith in abstract reason; the power of the human mind to overcome obstacles and solve problems. The Right rely more strongly on the wisdom of human experience; there are some things experience shows to be true, even if reason can’t precisely or thoroughly explain why.

Then, in 2008, along came social psychologist Jonathan Haidt and his TED talk The Moral Roots of Liberals and Conservatives. Haidt seemed to be on the same quest to understand the differences between liberalism and conservatism as me, but he approached it from the perspective of psychology rather than history.

Haidt’s talk resonated with me deeply and, in retrospect, it is now clear that it marked a turning point in my intellectual journey. It seemed to corroborate the conclusions I had reached from my own reading of history. I was so enthralled by his talk that I wrote to him and told him so, which was something I’d never done before. I explained that I am not a social scientist, but rather an amateur enthusiast who enjoys reading and thinking about these topics, and I explained the convergence of his thinking and mine. To my surprise and delight he wrote back. He gave me permission to publish our correspondence:

I get a lot of emails from ‘amateurs,’ and I rarely find that they fit with so much else that I am reading and thinking as yours has. I think you have nailed one of the few best candidates for being a single principle that characterizes the lib-con dimension. (No one principle gets 70% of it, but this one, and the openness-to-experience one, are good candidates). I think that the five [moral] foundations are like taste buds, everyone’s got them, but your reason/experience split may help explain why some people then construct a morality from logic, for which tradition is irrelevant; others, like Burke, see wisdom in accumulated experience.

As you know, [Thomas] Sowell makes a very compatible case, about why liberals are so prone to dangerous abstractions unmoored from reality. (and I’m a liberal, but a somewhat anti-rationalist one).

I’m also pleased that you have read my work so closely, and apply it so deftly. May I ask what your own political leanings are?

I replied that I’m conservative. He asked if I’d like to review the manuscript of what was then his forthcoming book, The Righteous Mind. I was flattered and, of course, I agreed to do so. My biggest claim to fame to date is that my name appears in the acknowledgments.

My encounter with Haidt and discovery of his work opened up a whole new realm for me to explore that I hadn’t previously considered: psychology. In the years since The Righteous Mind, I’ve read many of the studies Haidt refers to in his book and online lectures.1 I also read books on related topics such as:

- Predisposed: Liberals, Conservatives, and the Biology of Political Differences, by John R. Hibbing, Kevin B. Smith, and John R. Alford.

- The Cave and the Light: Plato Versus Aristotle and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization, by Arthur Herman.

- Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect, by Matthew D. Lieberman.

- The Social Animal: The Hidden Sources of Love, Character, and Achievement, by David Brooks.

- Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960 – 2010, by Charles Murray.

Little did I know there is a formal name for what I was doing. I was constructing a “nomological network of cumulative evidence.” This is a process by which evidence is gathered and organized in support of a hypothesis that a particular human trait is an evolutionary adaptation. It is a formalized version of consilience, and I learned of it by watching a lecture delivered by the psychologist Gad Saad entitled ‘Departures from Reason: When Ideology Trumps Science.’

Saad lists several categories of evidence that can make up a nomological network, including psychological, cross-temporal, cross-cultural, theoretical, and medical. I subsequently discovered a research paper entitled Evaluating Evidence of Psychological Adaptation by David P. Schmitt and June J. Pilcher, who include the additional categories of physiological, genetic, phylogenetic, and hunter-gatherer.2

Common themes emerged once again, building upon earlier ones, which eventually led me to formulate my Cognitive Theory of Politics. In brief, my theory holds that the political Left and Right are best understood as psychological profiles featuring different combinations of ‘moral foundations’ (to which Haidt alluded in his email and later explored in his book) and cognitive style. Psychological profiles operate within the social environments, circumstances, history, and traditions in which they are immersed, and it is from these profiles that beliefs, ideologies, values, principles, and policies follow. To define ideologies in terms of beliefs, values, etc., is to confuse cause and effect.

Moral foundations are evolved psychological mechanisms of social perception, subconscious intuitive cognition, and conscious reasoning described by Haidt in The Righteous Mind. They are pattern recognition modules in the psyche that operate like subconscious radars, constantly scanning the social environment for thought and behavior that once represented opportunities or threats to our genetic ancestors, and sending flashes of affect—gut feelings, intuitions—forward into consciousness when they are detected.

Haidt allows that there are probably many moral foundations, but he has focused his efforts on identifying the most powerful. He’s identified six so far, summarized as follows in The Righteous Mind on pages 178-179 unless otherwise noted:

- Care/Harm (sensitivity to signs of suffering and need)

- Fairness/Cheating (sensitivity to indications that another person is likely to be a good or bad partner for collaboration and reciprocal altruism)

- Liberty/Oppression (sensitivity to, and resentment of, attempted domination)

- Loyalty/Betrayal (sensitivity to signs that another person is (or is not) a team player)

- Authority/Subversion (sensitivity to signs of rank or status, and to signs that other people are (or are not) behaving properly given their position)

- Sanctity/Degradation (sensitivity to pathogens, parasites, and other threats that spread by physical tough or proximity)

He welcomes critiques of those he’s found and suggestions for additional ones.

He calls the first three foundations the “individualizing” foundations because their main emphasis is on the autonomy and well-being of the individual. The latter three are “binding” foundations because they help individuals form cooperative groups for the mutual benefit of all members. In his TED Talk, Haidt argued that moral foundations are the “tools in the toolbox” that make human society possible.

Cognitive styles, on the other hand, are ways of thinking; operating systems, if you will, like Windows and iOS, that process information received from the social environment. There are two predominant cognitive styles, traced through 2,400 years of human history by Arthur Herman in his book The Cave and the Light: Plato and Aristotle and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization, in which Plato and Aristotle serve as metaphors for each, summarized in the following two short passages:

Despite their differences, Plato and Aristotle agreed on many things. They both stressed the importance of reason as our guide for understanding and shaping the world. Both believed that our physical world is shaped by certain eternal forms that are more real than matter. The difference was that Plato’s forms existed outside matter, whereas Aristotle’s forms were unrealizable without it. (p. 61)

The twentieth century’s greatest ideological conflicts do mark the violent unfolding of a Platonist versus Aristotelian view of what it means to be free and how reason and knowledge ultimately fit into our lives (p.539-540)

Plato thought that everything in the real world is but a pale imitation of its ideal self, and it is the role of the enlightened among us to help us see the ideal and to help steer society toward it. This is the style of thinking behind RFK’s “I dream things that never were and ask ‘Why not?’” John Lennon’s “Imagine,” President Obama’s “Fundamentally Transform,” and even Woodrow Wilson’s progressivism.

Aristotle agreed that we should always strive to improve the human condition, but argued that the real world in which we live sets practical limits on what’s achievable. The human mind is not infinitely capable, nor is human nature infinitely malleable. If we’re not mindful of such limitations, or if we try to ‘fix’ them, our good intentions can end up doing more harm than good and lead us down the proverbial road to hell.

These two cognitive styles can be thought of, respectively, as WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) and holistic. In The Righteous Mind, Haidt describes the peculiarities of WEIRD individuals, as follows:

WEIRD people think more analytically (detaching the focal object from its context, assigning it to a category, and then assuming that what’s true about the category is true about the object). (p. 113)

[WEIRD thinkers tend to] see a world full of separate objects rather than relationships. (p. 113)

Putting this all together, it makes sense that WEIRD philosophers since Kant and Mill have mostly generated moral systems that are individualistic, rule-based, and universalist. (p. 113-114)

Worldwide, this kind of thinking is a statistical outlier because most people and cultures think holistically.3 Holistic thinkers tend to see a world full of relationships rather than objects, and they have a stronger tendency toward consilience. As Haidt explains:

When holistic thinkers in a non-WEIRD culture write about morality, we get something more like the Analects of Confucius, a collection of aphorisms and anecdotes that can’t be reduced to a single rule. (p. 114)

WEIRD Platonic rationalism and holistic Aristotelian empiricism can be thought of as the two ends of a spectrum of cognitive styles. Few people are at the extremes; most are somewhere in between.

The psychological profiles of Left and Right differ in the degree to which they tend to favor the cognitive styles and the moral foundations. A series of studies of cognitive styles has found that “liberals think more analytically (more WEIRD) than conservatives”:

[L]iberals think more analytically (an element of WEIRD thought) than moderates and conservatives. Study 3 replicates this finding in the very different political culture of China, although it held only for people in more modernized urban centers. These results suggest that liberals and conservatives in the same country think as if they were from different cultures.4

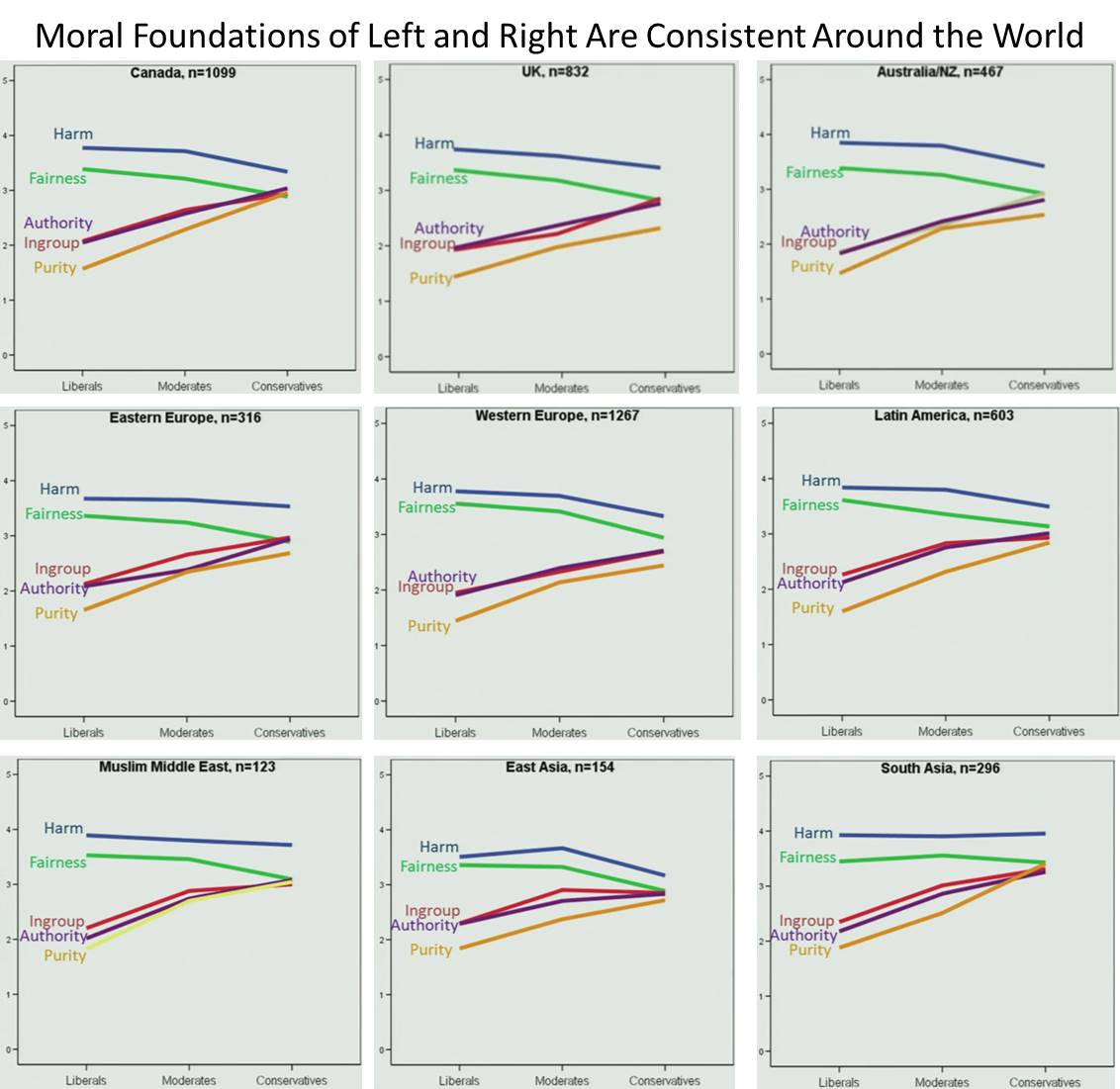

Haidt’s studies of moral foundations show that liberals tend to employ the individualizing foundations and, of those, mostly the care/harm foundation, whereas conservatives tend to use of all of them equally. There’s no conservative foundation that’s not also a liberal foundation but, for all practical purposes, half of the conservative foundations are unavailable to liberal social cognition. The graphic below comes from Haidt’s TED Talk, and it shows that this pattern holds true in every culture studied on every continent, suggesting it is a human universal.

‘Ingroup’ stands in for the ‘Loyalty/Betrayal’ foundation. The ‘Liberty/Oppression’ foundation, added to the first 5 foundations later by Haidt and his researchers, is absent.

Haidt finds that libertarians emphasize the liberty/oppression foundation more heavily than the others. He calls each configuration of moral foundations a moral matrix, in the sense that they define the reality in which each of us lives, much like in the movie The Matrix.

In sum, the liberal psychological profile tends toward the Platonic cognitive style combined with the three-foundation moral matrix. The conservative profile leans toward the Aristotelian cognitive style with the all-foundation moral matrix. The libertarian profile seems to be made up of the Aristotelian style combined with a moral matrix that emphasizes liberty/oppression more than the other foundations.

As I have argued before, concepts like liberty, equality, justice, and fairness take on different—even mutually exclusive—meanings depending on which psychological profile is interpreting them. The Left’s bias toward outcome-based conceptions of ‘positive’ liberty seems to follow naturally from its profile of Platonic rationalism focused on the moral foundation of care. The Right’s tendency to favor process-based conceptions of ‘negative’ liberty follows from its profile of Aristotelian empiricism in combination with all of the moral foundations.

It’s almost as if Left and Right are speaking different languages, in which each uses the same words but attaches starkly different meanings to them. Both sides agree that liberty is a great thing, but because neither side realizes that their understanding of it is different from that of the other they talk past one another, or worse, assume their opponent is stupid, ignorant, or wicked due to the failure to grasp concepts that in their own minds are self-evident.

The American economist and social theorist Thomas Sowell describes the way these two profiles have played out in the real world since the late 1700s in his book A Conflict of Visions: Ideological Origins of Political Struggles. Liberal psychology is reflected by thinkers like Godwin, Condorcet, Mill, Laski, Voltaire, Paine, Holbach, Saint-Simon, Robert Owen, and G.B. Shaw. The conservative profile is seen in the likes of Smith, Burke, Hamilton, Malthus, Hayek, and Hobbes.

A Cognitive Theory of Politics can help us to improve our understanding historical events. For example, Sowell observes that the liberal ‘vision,’ or psychological profile, can be seen as the engine of the French Revolution. Jonathan Haidt made the same observation in a lecture he gave at the Stanford University Center for Compassion and Altruism Research (CCARE) entitled “When Compassion Leads to Sacrilege.” In contrast, Sowell argues that the American founding was a fundamentally conservative movement. A reading of The Federalist Papers through the lens of the Cognitive Theory of Politics bears him out, and Burke—who supported the American Revolution but opposed the French Revolution—would probably agree.

Importantly, the Cognitive Theory can shed new light on current social trends as well. For example, professors who have incurred the wrath of campus social justice protesters such as Bret Weinstein, Michael Rectenwald, and Nicholas and Erika Christakis consider themselves left of center. This partly explains why they were so taken aback by the ferocity of the attacks against them; it seemed like friendly fire out of the blue.

But was it? I don’t think so. The split between the traditional Left—exemplified by the professors mentioned above—and the social justice Left is one of cognitive style. Both groups tend toward the liberal moral matrix, but the cognitive style of the social justice Left seems to be much closer to the Platonic rationalist end of the spectrum than does the more traditional Left. The most egregious ‘crime’ of the targeted professors seems to be that they’re Aristotelian thinkers. It’s not so much what they think that elicits the ire of the social justice left, it’s how they think.

Cognitive style is a different kind of moral foundation that overlays the six so far identified by Haidt, and it seems to be decisive in determining how liberals, progressives, conservatives, and libertarians prioritize the others. The political polarization of America described by Charles Murray in his book Coming Apart is best understood as a self-sorting of the population based primarily on cognitive styles.

A Cognitive Theory of Politics offers a new lens through which we can better understand human history and more clearly see ourselves and each other. Using this tool, we can better understand how we got to where we are, what’s happening to us now, and the available paths forward. A more accurate, science-based, universal understanding of the ‘Social Animal’ (humans) by the social animal might break the language barrier between Left and Right and provide a common foundation of knowledge from which productive debate can ensue.

References:

1 Haidt, J. (2001). The Emotional Dog and its Rational Tail: A Social Intuitionist Approach to Moral Judgement. Psychological Review. 108, 814-834.

Haidt, J., & Joseph, C. (2004). Intuitive Ethics: How Innately Prepared Intuitions Generate Culturally Variable Virtues. Daedalus, pp 55-56, Special Issue on Human Nature.

Haidt, J., & Graham, J. (2007). When Morality Opposes Justice: Conservatives Have Moral Intuitions That Liberals May Not Recognize. Social Justice Research.

Haidt, J. & Kesebir, S.. (2007). In the Forest of Value: Why Moral Intuitions Are Different From Other Kinds. In H. Plessner, C. Betsch, and T. Betsch (eds.) A New Look On Intuition in Judgment and Decision Making.

Haidt, J., & Joseph, C. (2007). The Moral Mind: How 5 Sets of Innate Moral Intuitions Guide the Development of Many Culture-Specific Virtues, and Perhaps Even Modules. In p. Carruthers, Sl. Laurence, and S. Stich (eds.) The Innate Mind, Vol 3. New York: Oxford, pp 367-391

Haidt, J. (2007). The New Synthesis in Moral Psychology. Science, 316, 998-1002.

Haidt, J. (2007) Moral Psychology and the Misunderstanding of Religion. Published on www.edge.org, 9/9/07

Haidt, J. (2008). Morality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3., 65-72.

Haidt, J. (2008). What Makes People Vote Republican? Published on www.edge.org 9/9/08

Haidt, J., & Graham, J. (2009). Planet of the Durkheimians, Where Community, Autority, and Sacredness are Foundations of Morality. In J. Jost, A. C. Kay, and H. Thorisdottir (eds.), Social and Psychological Bases of Ideology and System Justification.

Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. (2009). Liberals and Conservatives Use Different Sets of Moral Foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 1029-1046.

Haidt, J., Graham, J., & Joseph, C. (2009) Above and Below Left-Right: Ideological Narratives and Moral Foundations. Psychological Inquiry, 20, 110-119.

Haidt, J., & Kesebir, S. (2010) Morality. In S. Fiske, & D. Gilbert (eds.) Handbook of Social Psychology, 5th Edition.

2 ‘Evaluating Evidence of Psychological Adaptation: How Do We Know One When We See One?’ by D. P. Schmitt and J. J. Pilcher, Psychological Science 2004 Oct;15(10):643-9.

3 Henrich, J., Heine, S., Norenzayan, A., (2010) ‘The Weirdest People in the World?’, Behavioral and Brain Sciences (2010) 33, 61–135 doi:10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

4 ‘Liberals Think More Analytically (more “WEIRD”) Than Conservatives,’ J. Haidt et al, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Volume: 41 issue: 2, page(s): 250-267 Article first published online: December 24, 2014; Issue published: February 1, 2015 https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214563672