Top Stories

What Has Capitalism Ever Done For Us?

Like Reggie in Monty Python’s The Life of Brian, they demand to know: “What has capitalism ever done for us?”

When bemoaning the evils of capitalism, often from the soapbox of internet-connected smartphones or laptops, opponents of the free market are wont to wax lyrical about increasing income inequality. The rich are richer than ever before, because they hog obscene amounts of wealth that could be put to better use by plebs who are slaves to ‘the man,’ oppressed under the obligation that they toil endlessly for their wage. Like Reggie in Monty Python’s The Life of Brian, they demand to know: “What has capitalism ever done for us?”

In the mouth of the anti-capitalist activist, ‘capitalism’ has become a dirty word. It conjures images of bloated, greedy, rich one-percenters reclining behind piles of cash as they exploit their low paid workers, hoarding profits borne of the ethic of consumerism, which manifests itself in millions of brainwashed souls mindlessly handing over their meagre earnings for the instant gratification that comes from buying the next unneeded gizmo.

Such a dreary summation sells capitalism short. Capital itself is nothing more than privately owned money or assets used to start or invest in businesses that create products or services that other people may want. Everything that we enjoy on a day-to-day basis from housing, clothing and food, to entertainment, has been produced using capital. Even essential public services are funded by the tax collected from private wealth generated by capital.

In the manorial system of rural economies past, the wealthy and privileged strata of society owned everything and the serfs who worked the land were indentured servants, with no means of escaping from their economic situation. Certain areas of the lands owned by the lord of the manor were available for ‘free peasants’ to farm for rent payable to the lord. Quality of life for peasants was subsistence level. When conditions were good, life was good, but when the crops failed through bad weather or blight, then life was hard. During this period, wealth was a zero sum game: goods and money exchanged hands, but little new wealth was created.

Starting in the 13th century, the common land available to the peasantry began to be ‘enclosed.’ Peasants could no longer freely farm the land and the adoption of better farming practices on the larger enclosed tracts of land meant that not so much manual labour was required and many peasants faced ruin. The new landless working class then sought employment in the new industries being developed during the 18th century. The industrial revolution that followed, with its mass production and factory work enabled this new working class to exchange their labour for a wage and to free themselves from a hand-to-mouth existence on the land. In the era of free enterprise, innovation, and capital investment, it was possible for new wealth to be created on a large scale.

In the Parable of the Talents, Jesus tells the story of a master who went on a trip and left large sums of money with his trusted servants according to their ability. The most able was given five talents, another was given two talents, and the third servant was given one. While the master was away, the servants with five and two talents invested them wisely. By the time the master had returned from his extended journey, they had doubled the value of the talents they had been given. The third servant, fearful of displeasing his master, simply dug a hole and buried his talent. When the master returned, he rewarded the first two servants with extra responsibility, while the third servant was punished for failing to use his single talent productively. In the story, using capital to produce more wealth is beneficial not only to the master but also to the servants who were rewarded for their entrepreneurship. And in producing the wealth through judicial investment, goods and services of value were created that enhanced the lives of the people who were willing to exchange money for them.

When the profit motive is described as ‘greed’ or ‘selfishness,’ it comes very close to what is actually true. The free market is driven by radical self interest. While at first glance this may seem to be a negative, in fact the opposite is true. Businesses are motivated to make money, otherwise what is the point of carrying on a business at all? Consumers are only interested in products or services that have value to them and they will only pay the price that they are willing to pay. In order to satisfy their customers while also making a profit, businesses must therefore compete with each other by making efficient use of resources. In this way the self-interest of the entrepreneur is moderated by the forces of competition.

Anti-capitalist activists focus on the profits made by big business and see them as excessive. But profits represent new wealth created. Successful entrepreneurs don’t get a larger slice of the pie, they make the whole pie bigger; even though they themselves have a big slice, there is more residual pie to go around than before.

* * *

Critics of capitalism view employment as exploitation. The worker is the one who generates the value, and yet they are paid a fraction of the profits made by the employer. In this model, the worker is ‘forced’ to sell their labour power for a wage. But this ignores the risk, time, energy directed by the capitalist into his enterprise. It ignores the voluntary nature of employment, and the benefits of being able to exchange a skill set for units of stored value. It also ignores the benefits of being able to exchange wages for increasingly inexpensive and more abundant goods.

But let us for a moment accept the exploitation of labour model as correct; if employment is exploitative, then what is the proposed alternative?

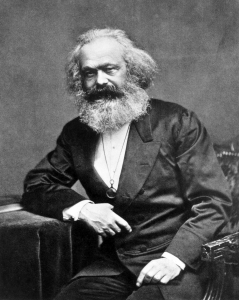

The Labor Theory of Value which is central to the economic philosophy of Karl Marx is used to demonstrate that workers are exploited by capitalism. According to this theory, the value of a commodity can be estimated by the number of hours of labour that were required to produce it. However, this fails to fully understand the subjective reasons we desire any given object. This can be illustrated by the words of economist and theologian the Reverend Richard Whately who noted that pearls do not “fetch a high price because men have dived for them; but on the contrary, men dive for them because they fetch a high price.”

If you’ve decided that products are only valued because of the number of hours that have gone into producing them, then the next logical conclusion is that any profits made by the entrepreneur are immoral. The means of production must therefore be better off in the hands of the workers themselves. But if profits are out, then the motivation to produce is gone, the price signal is gone, and production decisions must then be collectively planned. Because consensus by a large and disparate body of people requires representation, it is inevitable that only a small number of people end up at the top of the chain, making decisions that the collective whole must abide by. In other words, in order for such a system to work, coercion is required. It is authoritarian.

Even Friedrich Engels, co-author with Marx of The Communist Manifesto, foresaw that planning under a system based on ‘labor hours’ as opposed to subjective value and the competitive price system would be unworkable:

To desire in a society of producers who exchange their commodities, to establish the determination of value by labour time, by forbidding competition to establish this determination of value through pressure on prices in the only way in which it can be established, is therefore merely to prove that…one has adopted the usual Utopian disdain of economic laws…Only through the undervaluation and overvaluation of products is it forcibly brought home to the individual commodity producers what things and what quantity of them society requires or does not require…If now competition is to be forbidden to make the individual producers aware, by the rise or fall of prices, how the world market stands, then their eyes are completely blinded.

During a state visit to the US in 1989, former Russian president Boris Yeltsin made an unscheduled stop at a Randall’s grocery. When he saw the abundance of produce on offer he was astounded. In his autobiography, Yeltsin wrote:

When I saw those shelves crammed with hundreds, thousands of cans, cartons and goods of every possible sort, for the first time I felt quite frankly sick with despair for the Soviet people. That such a potentially super-rich country as ours has been brought to a state of such poverty! It is terrible to think of it.

Two years later, Yeltsin left the Communist Party and began a reform process that would see him become the first democratically elected Russian leader and preside over the demise of the Soviet Union.

The centrally planned communist Soviet economy based on the Marxist Labour Theory of Value, simply could not compete with the abundance that we take for granted in modern capitalist societies. Without the knowledge that the price signal sends, top down central planning results in inefficiencies and waste, while at the same time denying individuals freedom and choice. Who would you trust more? Human beings driven by self interest who are in the business of providing goods and services that please consumers, or human beings driven by self-interest in positions that grant them enormous bureaucratic power over others?

A collectivist system requires that people change their innate motivations. Instead of striving to improve their individual lot, they must look at the big picture and elevate the collective good above their own self interest. History has demonstrated that this is an unrealistic expectation, no matter how preferable it may seem on paper. A capitalist system, however, does not require that individuals change their very nature, in fact it relies on the motivation of self-interest. That is not to say that in a capitalist system there are no philanthropists or big-picture thinkers and creatives. But a capitalist system does not require that everybody thinks and acts in this way in order for it to succeed.

Critics of capitalism hark back to pre-capitalist societies as exemplars of egalitarianism. But, without exception, people choose to break free of these societies when given the chance. They willingly embrace a capitalist system; they want things, as do we all. Tellingly, most critics of the capitalist system do not willingly remove themselves from it. As they continue to enjoy the benefits of smartphones, supermarkets, and automobiles, and watch Netflix on their MacBooks, they are supporting the very system they claim to oppose. And why wouldn’t they? Any sane person who has the good fortune to benefit from the capitalist system, will.

* * *

Private property ownership, the foundation on which capitalism stands, is the principle that allows people to benefit from their own labour. If you make something, you get to keep it. It drives creativity and productivity, and economic systems that deny this right result in perverse effects that kill motivation, and quash personal pride with often catastrophic results.

But no system is perfect. Social and income inequality exist within capitalist societies as they have existed in every other economic system that has been tried. It is true that many people inherit wealth and that this gives them a head start in life. It can be argued that this isn’t fair and that would probably be right; the reality is that life very often isn’t fair. Not everybody is equally talented or skilful. Likewise, not everybody is presented with the same opportunities to succeed. Recall the Parable of the Talents; the servant who buried his capital didn’t have the skills or drive necessary to make the capital work in a way that generated more wealth. That is why, in most capitalist societies, provision is made for people who, for whatever reason, are unable to thrive.

Often this takes the form of social welfare, or the ‘safety net,’ and is complemented by private beneficent societies such as church groups and charities. But the high cost of state-sponsored welfare and the deleterious effects of intergenerational welfare dependency mean that alternatives need to be found. Many ideas have been floated which seek to address social inequality including the Universal Basic Income and work placement subsidies, which are said to be largely self-financed by reductions in welfare and crime. Cutting edge thinkers also see opportunities in blockchain technology, which, through the creation of ‘smart contracts,’ allows people to income swap in a way that does not require central planning or administration. Any solutions that seek to address inequalities must be carefully balanced against individual freedoms. As Milton Friedman so eloquently stated, “The society that puts equality before freedom will end up with neither. The society that puts freedom before equality will end up with a great measure of both.”

Other problems arise within markets when large corporate entities lobby government to manipulate the market in their favour through the use of regulations, subsidies, and labour legislation. This influence then upsets market equilibrium leading to shortages, surpluses, and monopolies. Governments also meddle in the market to protect certain enterprises from collapsing; one well known example is the financial bailouts of banks. This corporatism, or crony-capitalism, results in mis-management and distortion of markets, along with intended and unintended negative effects on the economy. Mega-corporations aided by government regulations monopolise the market-place.

Many of those who rightly critique these unethical practices, wrongly blame capitalism and markets themselves. The trouble is that governments in capitalist societies are generally too large, and all too ready to bow to corporatist pressure, and grant favours in exchange for political donations. Corporations then find themselves in control of the levers of government. The problem isn’t that markets are too free, but that they are not free enough. Corporatism is an argument against government and the corrupting influence of power, not against capitalism and the marketplace. As Thomas Jefferson so wisely said, “A wise and frugal government, which shall restrain men from injuring one another, shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned.”

Free market capitalism and individualism grant us levels of freedom unheard of in human history. Wealth creation is not a zero sum game. It is not finite. We can’t cut it up into little pieces and share them out evenly. While building their own personal new wealth, billionaire entrepreneurs are creating more wealth overall through job creation and by providing value to consumers that enriches us all. Income inequality may have increased, but a greater proportion of people than ever before enjoy wealth that only two or three generations ago would have been unfathomable. We need to be honest about the failings of human beings, and to acknowledge that rather than causing these failings, capitalism minimises their negative impact. We need also to remember the often gruesome outcomes of collectivist alternatives. People who seek to redress the inequality and dysfunction that prevails in our modern societies are to be lauded, but vilifying capital and the free market is misguided and attacks the very system that has enabled life to improve for the vast majority of the global population.