History

The Behavioral Ecology of Male Violence

Understanding patterns of lethal violence among humans requires understanding some important sex differences between males and females.

“Aggressive competition for access to mates is much

more beneficial for human males than for females…”

~Georgiev et al. 1

Understanding patterns of lethal violence among humans requires understanding some important sex differences between males and females. Globally, men are 95 percent of homicide offenders and 79 percent of victims.2 Sex differences in lethal violence tend to be remarkably consistent, on every continent, across every type of society, from hunter-gatherers to large-scale nation states. In their 2013 study on lethal violence among hunter-gatherers, Douglas Fry and Patrik Söderberg’s data showed that males committed about 96 percent of homicides and were victims 84 percent of the time.3 In her study on violence in non-state societies, criminologist Amy Nivette shows that, across a number of small-scale pastoralist and agriculturalist societies, males make up 91-98 percent of killers.4 To illustrate the consistency of this relationship even further: we see the same pattern among chimpanzees, where males make up 92 percent of killers and 73 percent of victims.5

To be sure, there is some cross-cultural variation. While I can find no well-studied population where women are known to commit more lethal violence than men, there are some societies where women make up an equal number, or even the majority, of homicide victims. These societies generally seem to have low rates of homicide overall, as the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime mentions in their 2013 study on global homicide:

Available data suggest that in countries with very low (and decreasing) homicide rates (less than 1 per 100,000 population), female victims constitute an increasing share of total victims and, in some of those countries, the share of male and female victims appears to be reaching parity.

Hong Kong, with a low homicide rate overall, has a comparatively smaller sex difference in homicide offending, and women make up a majority of homicide victims at 52 percent. Yet even in Hong Kong, males commit 78 percent of reported homicides. The world over, the majority of homicide offenders and victims tend to be reproductive-age males, between their late teens and early 40s.

To understand why this pattern is so consistent across a wide variety of culturally and geographically diverse societies, we need to start by looking at sex differences in reproductive biology.

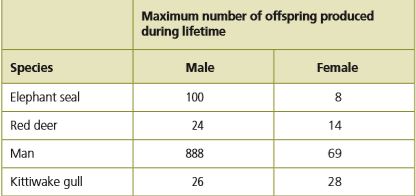

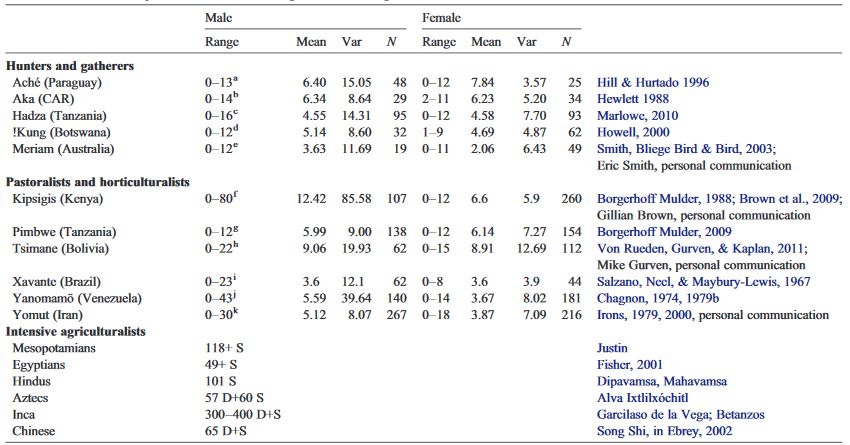

Biologically, individuals that produce small, relatively mobile gametes (sex cells), such as sperm or pollen, are defined as male, while individuals that produce larger, less mobile gametes, such as eggs or ovules, are defined as female. Consequently, males tend to have more variance in reproductive success than females, and a greater potential reproductive output. Emperor of Morocco, Moulay Ismael the Bloodthirsty (1672–1727) was estimated to have fathered 1171 children from 500 women over the course of 32 years,6 while the maximum recorded number of offspring for a woman is 69, attributed to an unnamed 18th century Russian woman married to a man named Feodor Vassilyev.

Across a wide variety of taxa, the sex that produces smaller, mobile gametes tends to invest less in parental care than the sex that produces larger, less mobile gametes. For over 90 percent of mammalian species, male investment in their offspring ends at conception, and they provide no parental care thereafter.7 A male mammal can often increase his reproductive success by seeking to maximize mating opportunities with females, and engaging in violent competition with rival males to do so. From a fitness perspective, it may be wasteful for a male to provide parental care, as it limits his reproductive output by reducing the time and energy he spends competing for mates.

For a female, in contrast, maximizing her reproductive success usually stems less from directly competing for mating opportunities than from securing the resources and protection necessary for her offspring to live and grow to adulthood. This is clearly visible among mammals, where females spend significant time and energy gestating (carrying a child) and lactating, which males cannot do. As a consequence, the amount of time and energy directly invested in children is necessarily greater among females than males, at least during fetal development and early childhood.

Predictably, among humans, males engage in more direct, violent competition for mates than females do, and females provide more caregiving than males do. However, humans are unique in that some male participation in caregiving is ubiquitous across cultures.8 Human infants are particularly helpless during early development, requiring extensive provisioning and caregiving.9 Human males face the same tradeoff between securing mating opportunities and providing parental care that males of other species face, and the extent to which males utilize either of these strategies can vary significantly due to social and ecological factors.

Noting these sex differences in reproductive biology and parental investment is important because they help explain why males tend to engage in more violence than females.10 Aggressively engaging in violent conflict is more likely to reduce a female’s fitness, as it may bring unnecessary danger to her offspring, or cause an injury that may prevent her from reproducing in the future. For a male, however, violent conflict can potentially increase his reproductive success through increases in status,11 or by aggressively monopolizing access to key resources.12 Among the Yanomami of the Amazon,13 and the Nyangatom of East Africa,14 for example, males who participate in more violence and warfare have increased reproductive success. Even in the contemporary United States, there is evidence that more violent males have more sexual partners.15

Among the Ache hunter-gatherers of Paraguay, the children of men who have killed are more likely to survive to adulthood.16 Male parental investment can also act to deter violence among the Ache, as children without fathers are more likely to be killed by other males.17

Conversely, among the Waorani of the Amazon, more violent males do not have increased reproductive success.18 Whether a particular behavioral strategy is adaptive or not is closely related to social and ecological circumstances, and it is important to keep this in mind when thinking about sex differences and human evolution. I would not argue that males are ‘wired’ to be violent in any deterministic sense.

Rather, because of sex differences in parental investment and reproductive output, there are (and have been historically) more contexts where violent behavior may increase a male’s reproductive success compared to a female. And equally, there are more contexts where violent behavior may reduce a female’s reproductive success compared to a male. A young man who impregnates a woman and then goes to die in a war still leaves a child behind who may be cared for by the mother and her family, while a young pregnant woman who would fight faces a much greater fitness risk.

These sex differences have important implications for coalitionary violence. As behavioral ecologist Bobbi S. Low writes:

Pursuit of mating success leads mammalian males to involvement in coalitions more often involving nonrelatives, with higher risks and greater conflicts of interests. Pursuit of parental success…leads mammalian females to strive more often as individuals and in coalitions of relatives, with less conflict of interest and less risk.19

In regard to human societies, Low also notes that, generally, “Men appear to seek overt political power for direct reproductive gain (wives, owed reciprocity), while women seek resources for themselves and their offspring.”

When we see consistent patterns across diverse cultures, it likely tells us something important about our evolutionary history, and understanding trends we see today can help us better understand the selection pressures that occurred in the past. In anthropologist Martin King Whyte’s study on The Status of Women in Preindustrial Societies, he looked at sex roles across 93 nonindustrial societies of diverse subsistence types (hunter-gatherer, horticulturalist, pastoralist, agriculturalist, etc.) from all over the world.20 He found that in 88.5 percent of societies, only males participated in warfare, while in the remaining 11.5 percent, males still did all the fighting but women could provide aid. While there are undoubtedly examples of female participation in warfare throughout history,21 I am not aware of any society where female participation in warfare has ever equaled that of males.22

Now, an important caveat: not all violence can be explained in terms of adaptive strategies. Humans are not simply fitness-optimizing machines, and we can point to plenty of behaviors and practices across cultures that are likely not adaptive from a fitness standpoint.23, 24

However, when looking at the most common causes of lethal conflict across cultures, we can see a clear relationship between a male’s fitness interests and killings. Homicide often occurs in the context of revenge, fights over status, and sexual jealousy.25 Competition for territory and resources also plays a strong role, particularly in the context of coalitionary killings, such as in gang violence and warfare. Cross-culturally, revenge often occurs in the context of seeking vengeance for a relative that was killed, which may act to deter future attacks on the killer’s relatives, and thus increase his inclusive fitness. Revenge is also often related to fights over status against rival males. Furthermore, having high-status and being able to control desired territory and resources can often increase a male’s reproductive success, through mechanisms beyond just force, such as female choice, or by being a preferred partner in marriages arranged by a potential wife’s parents.26

As for homicide due to sexual jealousy, this often occurs in the context of the (real or perceived) threat of infidelity.27 This might be a male killing his wife’s lover, or his wife, out of a belief that she is cheating, or fears that she will leave him.

As these patterns indicate, male violence in humans often occurs in contexts where a man’s reproductive success is threatened, or where he may derive greater reproductive success from engaging in violence. Due to our evolutionary history, even in modern contexts where specific violent behaviors may not be fitness maximizing, such as in an armed robbery or gang violence, we can consider these behaviors to be, in part, a byproduct of a greater propensity among males to aggressively pursue status and gain resources in ways that would have increased their reproductive success in the past.28

With all this in mind, we can think about how the prevalence of lethal violence may be reduced today. Research in behavioral ecology indicates that violence is more likely to occur in contexts where defensible resources can be successfully monopolized through force.29 Importantly, these resources often also have the effect of increasing the reproductive success (or preventing a decline in the reproductive success) of the individuals that control them. Which resources are most valuable should vary based on socioecological context, but common ones would be food, territory, mates and varying forms of social capital (dominance rank, prestige, or other forms of status).

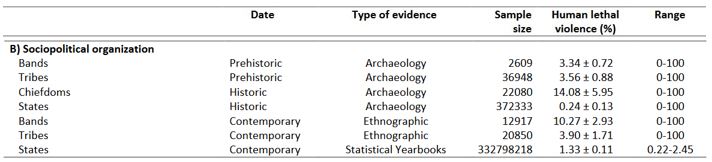

There is good evidence that contemporary nation states, particularly wealthy, industrialized ones, have some of the lowest rates of lethal violence in human history.30 Having laws and a police force perceived as legitimate by the population at large changes the incentives for lethal violence, increasing the costs and reducing the benefits for those who engage in such behavior. Furthermore, well-functioning states can resolve disputes that might otherwise have led to cycles of revenge raiding and blood feuds in other social contexts.31, 32, 33

Unsurprisingly, we see high rates of lethal violence in sectors outside the reach of, or poorly covered by, the influence of states, such as among gangs and organized crime. When it comes to high-demand products prohibited by the state, such as illegal drugs, it is violent organizations that effectively control these markets, as the state fails to offer a resolution when conflicts occur. In Codes of the Underworld, social scientist Diego Gambetta writes, “Mafia-like groups offer a solution of sorts to the trust problem by playing the role of a government for the underworld and supplying protection to people involved in illegal markets or deals.”34

U.S. attorney general Jeff Sessions unwittingly touched on this in an op-ed he wrote last year for the Washington Post, where he noted that, “Drug trafficking is an inherently violent business. If you want to collect a drug debt, you can’t, and don’t, file a lawsuit in court. You collect it by the barrel of a gun.” Sessions has consistently supported more extensive crackdowns on drug trafficking. One implication I draw from research in behavioral ecology is that legalizing many illegal drugs and having the state protect property rights for these products might reduce the lethal violence associated with the drug trade, as economist Milton Freidman argued decades ago.

There are other socioecological factors where we see an association with lethal conflict, such as the link between polygyny and war. Terrorist organizations such as Boko Haram and ISIS have exploited marriage inequality among young males by paying the brideprice (money or gifts given to a potential wife’s family), or providing wives, for recruits in the Middle East and West Africa.35 When some males monopolize access to wealth or mates, young males who are left out may behave violently to try and distinguish themselves, competing for control of such resources. As we might expect, there is evidence that higher rates of resource inequality within societies are associated with increased rates of violent conflict among men.36, 37

The approach I take here, rooted in behavioral ecology, does not necessarily conflict with genetics playing a role in the propensity to commit lethal violence. A review published in Advances in Genetics in 2011 found that roughly half the variance (50 percent) in aggressive behavior among both males and females is attributable to genetic factors.38 Importantly, however, there is also evidence for significant gene-environment interactions affecting violent behavior.39 Furthermore, when we see significant, and rapid, changes in rates of lethal violence in a single generation within a society,40 it points to the need to examine the role played by socioecology.

Likewise, some may object to my focus here on adaptive and material explanations for violent behavior, and instead argue for a greater role played by ideology and socialization. I have previously written about societies with ‘men’s cults,’ where young males often partake in dysphoric rituals, and are socialized to become warriors. Further, among the Gebusi of New Guinea, most homicides occur in the context of sorcery allegations,41 illustrating how cultural ideas can play a role in promoting violence.

However, the men’s cults are often dominated by elder males, who control the sexuality of young men and monopolize access to important resources and knowledge. Among the Gebusi, anthropologist Bruce Knauft found that sorcery accusations are often precipitated by lack of reciprocity in marriage exchanges. He writes, “In this sense sorcery homicide is ultimately about male control of marriageable women.” Even where socialization and ideological factors play a role in lethal violence, they may be a proxy for underlying fitness interests.

There is a concern among some social scientists and science writers that providing adaptive and biological explanations for violence has the effect of encouraging such behaviors. Anthropologist Douglas Fry argues that, “Naturalizing war creates an unfortunate self-fulfilling prophecy: If war is natural, then there is little point in trying to prevent, reduce, or abolish it.”

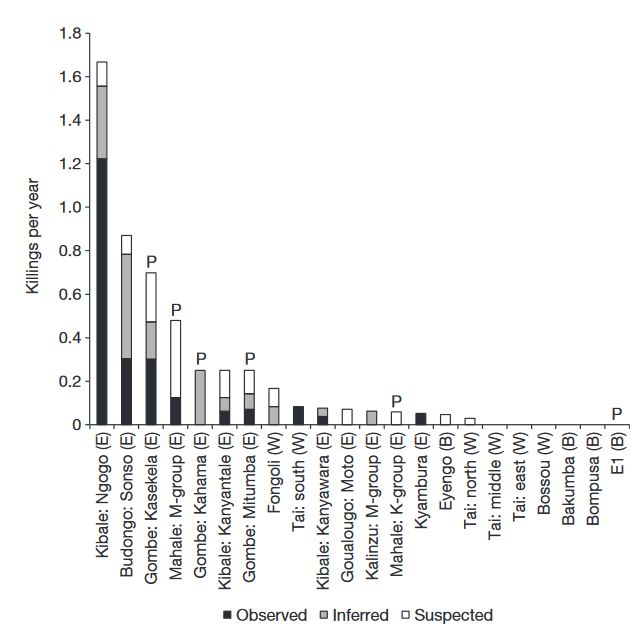

My argument here is that homicide and warfare are very much ‘natural’ behaviors, often tied to male fitness interests; however, such behaviors are sensitive to socioecological cues, and their prevalence can vary significantly across and within societies. Even among chimpanzees, we see significant variation in rates of lethal violence between different communities, even for those located near each other.

An important strength of the behavioral ecology approach to understanding human behavior is that it goes beyond more narrow ideas rooted in genetic determinism or social constructionism. Violence is not ‘innate’ in the sense of being predictably and rigidly determined by genes alone, nor is it the arbitrary result of socialization or cultural learning. Yet violence is nonetheless rooted in human biology, particularly in sex differences between males and females, and the prevalence of violence can vary substantially across and within cultures due to socioecological factors.

In understanding the cross-cultural trends, as well as accounting for the variation, we can better understand both why males everywhere are, on average, more violent than females, as well as how best to reduce the prevalence of violence within our own societies.

References:

1 Alexander V. Georgiev, Amanda C. E. Klimczuk, Daniel M. Traficonte, and Dario Maestripieri “When Violence Pays: A Cost-Benefit Analysis of Aggressive Behavior in Animals and Humans” Evol Psychol. 2013 Jul 18; 11(3): 678–699.

2 UNODC. 2013. Global Study on Homicide 2013. United Nations publication.

3 Fry, D. & Söderberg, P. 2013. Lethal Aggression in Mobile Forager Bands and Implications for the Origins of War. Science

4 Nivette, A.E. 2011. Violence in Non-State Societies. British Journal of Criminology

5 Wilson, M.L. et al. 2014. Lethal aggression in Pan is better explained by adaptive strategies than human impacts. Science

6 Oberzaucher, E. & Grammer, K. 2014. The Case of Moulay Ismael – Fact or Fancy? PLOS One

7 Royle, N.J. et al. 2012. The Evolution of Parental Care. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

8 Anderson, K.G. & Starkweather, K.E. Parenting Strategies in Modern and Emerging Economies. Human Nature

9 Dunsworth, H.M. et al. 2012. Metabolic hypothesis for human altriciality. PNAS

10 Campbell, A. & Cross, C. 2012. Women and Aggression. in The Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Perspectives on Violence, Homicide, and War (ed. by Shackelford, T. K. et al.) Oxford: Oxford University Press.

11 Glowacki, L. & Wrangham, R.W. 2013. The Role of Rewards in Motivating Participation in Simple Warfare. Human Nature

12 Glowacki, L. et al. 2017. The evolutionary anthropology of war. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization

13 Chagnon, N.A. 1988. Life Histories, Blood Revenge, and Warfare in a Tribal Population. Science

14 Glowacki, L. & Wrangham, R. 2015. Warfare and reproductive success in a tribal population. PNAS

15 Seffrin, P.M. 2016. The Competition–Violence Hypothesis: Sex, Marriage, and Male Aggression, Justice Quarterly

16 Hurtado, A.M. & Hill, K. 1996. Ache Life History: The Ecology and Demography of Foraging People. New York. Routledge

17 Hill, K. & Kaplan, H. 1988. Tradeoffs in male and female reproductive strategies among the Ache, Part 2. in Human Reproductive Behaviour: A Darwinian Perspective (ed. by Beltzig, L. et al.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

18 Beckerman, S. et al. 2009. Life histories, blood revenge, and reproductive success among the Waorani of Ecuador PNAS

19 Low, B.S. 1992. Sex, Coalitions, and Politics in Preindustrial Societies. Politics and the Life Sciences

20 Whyte, M.K. 1978. The Status of Women in Preindustrial Societies. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

21 Law, R. 1993. The ‘Amazons’ of Dahomey. Paideuma

22 Goldstein, J.S. 2001. War and Gender: How Gender Shapes the War System and Vice Versa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

23 Edgerton, R.B. 1992, 2010. Sick Societies. New York: Simon & Schuster.

24 Boyd, R. & Richerson, P.J. 2005. The Origin and Evolution of Cultures. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

25 Daly, M. & Wilson, M. 1988, 2009. Homicide. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers.

26 Apostolou, M. 2010. Parental choice: What parents want in a son-in-law and a daughter-in-law across 67 pre-industrial societies. British Journal of Psychology

27 Buss, D. 2000. The Dangerous Passion: Why Jealousy Is as Necessary as Love and Sex. New York: The Free Press.

28 von Rueden, C.R. & Jaeggi, A.V. 2016. Men’s status and reproductive success in 33 nonindustrial societies: Effects of subsistence, marriage system, and reproductive strategy. PNAS

29 Jaeggi, A.V. 2016. Obstacles and catalysts of cooperation in humans, bonobos, and chimpanzees: behavioural reaction norms can help explain variation in sex roles, inequality, war and peace. Behaviour

30 Gómez, J.M. et al. 2016. The phylogenetic roots of human lethal violence. Nature

31 Diamond, J. 2012. The World Until Yesterday. New York: Viking Press.

32 Keeley, L. 1996. War Before Civilization. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

33 Pinker, S. 2011. The Better Angles of Our Nature. London: Penguin Books.

34 Gambetta, D. 2011. Codes of the Underworld. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

35 Hudson, V.M. & Matfess, H. 2017. In Plain Sight: The Neglected Linkage between Brideprice and Violent Conflict. International Security

36 Wilson, M. & Daly, M. 1997. Life expectancy, economic inequality, homicide, and reproductive timing in Chicago neighborhoods. BMJ

37 Elgar, F.M. & Aitken, N. 2010. Income inequality, trust and homicide in 33 countries. European Journal of Public Health

38 Tuvblad, C. & Baker, L.A. 2011. Human Aggression Across the Lifespan: Genetic Propensities and Environmental Moderators. Advances in Genetics

39 Laucht, M. et al. 2014. Gene–Environment Interactions in the Etiology of Human Violence. Current Topics in Behavioral Neuroscience

40 Pridemore, W.A. 2007. Change and Stability in the Characteristics of Homicide Victims, Offenders and Incidents During Rapid Social Change. British Journal of Criminology

41 Knauft, B. 1987. Reconsidering Violence in Simple Human Societies. Current Anthropology.