Words Lose Their Meaning at Wilfrid Laurier University

Though different literary forms, the key message of both works was the same: beware any person or group that redefines words.

I know that references to George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984 have been overused in reference to the current crisis over freedom of expression at Wilfrid Laurier University. But I’m hoping my position as a Laurier professor will win sympathy from readers so that that they might indulge just one more tip of that hat to Orwell.

Orwell wrote 1984 not as a standalone work but as the fictional counterpart to an essay he had written titled: “Politics and the English Language.” The piquant ideas of the essay, published in 1946, were repackaged in more accessible form two years later in the exciting narrative of his novel.

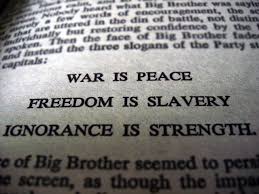

Though different literary forms, the key message of both works was the same: beware any person or group that redefines words so that they no longer align with facts, common sense, and common usage.

In the novel this idea is made blatantly obvious in the paradoxical mottos the totalitarian government requires its citizen to recite, such as: “War is Peace” and “Slavery is Freedom.” In the essay Orwell is equally straightforward stating: “Political language is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.”

As one of a small group of professors pushing for maximum freedom of expression and inquiry at my university, I’ve been personally frustrated by my colleagues who claim that some topics are “not up for debate” and that censorship is required when a counter-argument offends the feelings of certain individuals or groups.

However, professionally, as a researcher in the area of communication, I’ve been fascinated by the way my university’s free expression opponents provide a vivid illustration of Orwell’s theory of political language. The examples are numerous, but I’ll focus on just two.

Details of the Controversy

On November 10th the National Post broke the story of a Laurier Grad Student, Lindsay Shepherd, who got into trouble for showing her class a video clip from TVOntario that featured Jordan Peterson. It was a debate where Peterson argued against compelled speech, saying why he would not be forced to use non-gender specific pronouns like “Ze” and “Zer”. These newly created pronouns are now used by some transgendered people who prefer not to identify as either male or female.

The trouble for Shepherd came from two professors, Nathan Rambukkana and Herbert Pimlott, and a representative from the university’s Diversity and Equity Office, Adria Joel. They said the video should not have been shown and that doing so had created a “toxic environment” in the classroom.

Reaction from other media and the Canadian public grew slowly at first, but after a secret recording of the meeting was released by Shepherd, interest accelerated. The overriding opinion was uniform: Shepherd was right for neutrally showing two sides of a debate and her three interrogators — two professors and one administrator — were wrong.

Despite the overwhelming popular consensus that Laurier, and universities in general, should fairly present both sides of an argument, a substantial group of Laurier profs and students, bound by a far-left ideology, felt compelled to educate the public otherwise and so launched a counter-media campaign. Their first communications strategy, I’ll call it “the appeal to safety,” illustrates Orwell’s concepts of political language better than some of his own examples.

The Appeal to Safety

In “Politics and the English Language” Orwell describes how those hungry for power and position will use “meaningless words” to achieve their desired goals. He writes that they use words “which are almost completely lacking in meaning” that if used as intended, or substituted for clearer terms, would reveal “at once that language was being used in an improper way.”

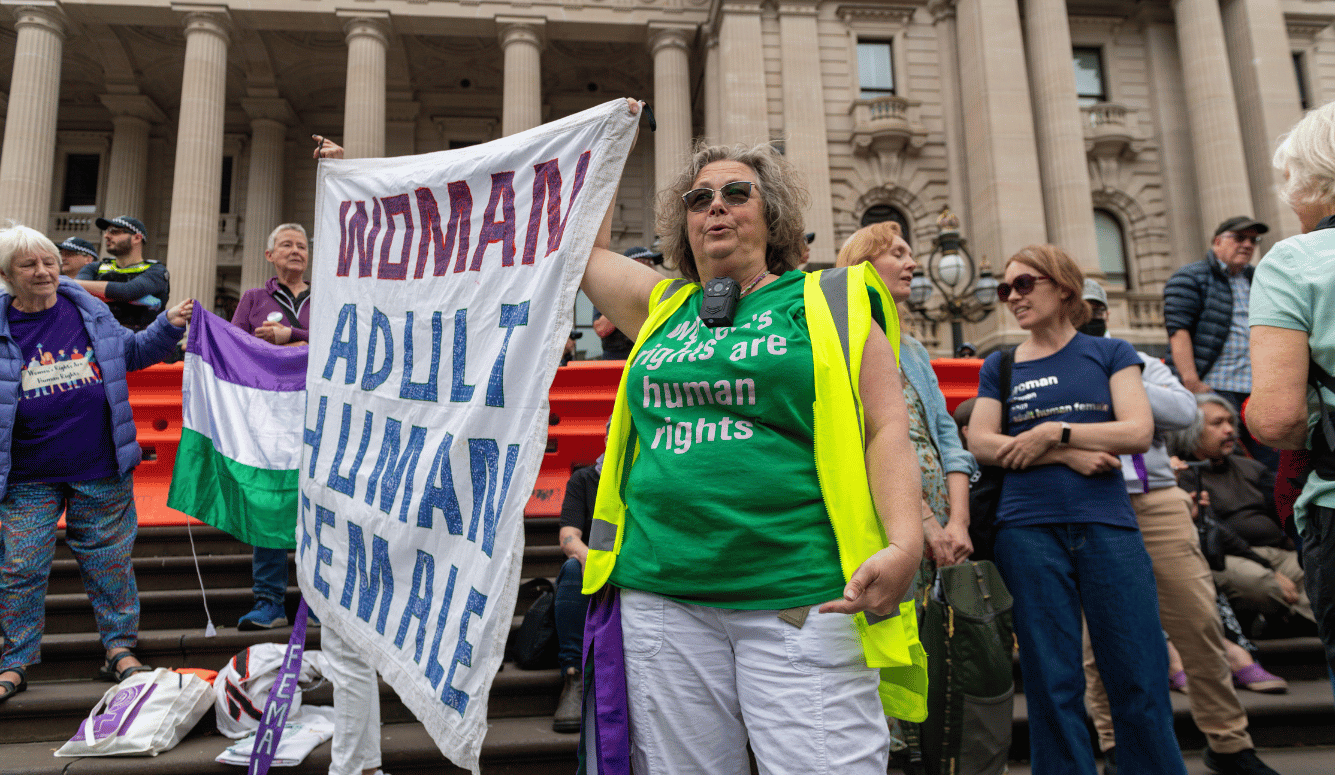

In media interviews, op-eds, and public letters posted to social media the leaders of this opposition group sought to redefine the meaning of harm. In popular understanding, harm to a human involves infliction of long-term damage that compromises normal appearance or function.

But this group jettisoned the established criteria and instead equated harm with taking offence and having one’s feelings hurt. Thus, under their new definition, they claimed students who found the ideas of Jordan Peterson objectionable and were exposed to them in a four minute video had been severely injured.

Furthermore, the injury was not isolated to just those who saw the clip of the debate. Even hearing that such a video had been aired on campus was enough to do mental harm to others. Echoing the party line with hyperbolic flourish, the op-ed of one Laurier activist proclaimed—

We need to acknowledge that debates that invalidate the existence of trans and non-binary people or dehumanize us based on gender are both a form of transphobia and gendered violence. There is no neutral way to demand that someone defend their very existence and their right to a safe school and work environment.

In addition to “gendered violence” the term, “epistemic violence” was also used in their communiques. In his essay Orwell makes us aware of those who use “pretentious diction” as a method of manipulation; they use special words “to dress up a simple statement and give an air of scientific impartiality to biased judgments.” Certainly, “gender violence” and “epistemic violence” have the ring of clinical authority and suggest the claims of the free speech opponents have empirical backing.

Unfortunately, clinical authority is not on their side. Their attempt to “give an appearance of solidity to pure wind” was exposed when news reports began citing the most up to date psychological research. Existing research suggests that, for the average person, no lasting harmful effects arise from exposure to ideas they might find offensive. Amongst clinical psychologists, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is currently considered the gold standard treatment for anxiety disorders, including PTSD. A core component of CBT is exposing a person to their fears as well as reducing behaviors which encourage avoidance. The underlying logic of this technique is that avoidance increases mental fragility while exposure decreases it.

One article debunking the concept of rampant “mental harm” being perpetrated on campus referenced the work of Emory University professor of psychology, Scott Lilienfeld. Reviewing all the scientific literature on “microaggressions”— innocuous actions, comments or facts perceived to be racist or sexist slights — Lilienfeld concludes those claiming such phenomena cause psychological harm are wrong; “there is little to no empirical evidence to support such claims.”

While their definition of harm and related claims were incredibly flawed, the logic of my campus’ free speech foes was not. They knew that proof of harm, mental or otherwise, would bolster support for their campaign to restrict certain ideas. So, when it was clear the public-at-large wasn’t buying the claim that videos from public television make classes unsafe, they changed tack and began claiming discussion of freedom of expression itself puts whole campuses under physical threat.

For example, in an open letter to university administration released November 24th and updated the 26th, a group of pro-speech-restriction Laurier faculty claimed the heated public discussion over freedom of expression had caused “our campuses to become unsafe.” They called on administration to “ensure the safety and protection of students and faculty who are being subjected to discrimination, harassment, and threats on their lives.”

I categorically condemn illegal activities done under the guise of freedom of expression. When I read this open letter my response was revulsion toward the perpetrators and sympathy for those targeted. In solidarity with those affected, that day I posted to my twitter account: “I always say: be civil, criticize the idea don’t attack the person, & never threaten.”

However, my sympathy diminished when, on the evening of November 26th, Global TV news investigated the “unsafe” state of my campus. They reported Waterloo Regional Police had received no complaints of harassment, let alone threats to life, from Laurier faculty or students. A similar piece in The Globe and Mail the next morning stated no complaints of harassment or threats had been filed with Laurier Campus police.

While I continue to abhor threats and harassment, in the absence of supporting evidence I’m left to wonder whether the faculty and students who claimed “threats on their lives” were sincerely concerned for their personal safety, or simply concerned that their position would gain popular support.

My campus’ free expression opponents probably realized their assertions of harm were reducing, not increasing, their credibility in the eyes of the public. Accordingly, around the end of November I noticed a refocusing of their messaging. The political language strategy that I now saw being emphasized I’ll call: “the appeal to contextualization.” It’s a strategy that again combines Orwell’s twin concepts of “meaningless words” and “pretentious diction.”

The Appeal to Contextualization

I say they refocused and began emphasizing this strategy, but it wasn’t new. It was employed right from the start of the controversy. In fact, it first makes its appearance in the recorded comments of professor Rambukkana.

Explaining to Shepherd why it was wickedness to air a debate that allowed equal time to Jordan Peterson’s views on gender-pronouns, Rambukkana says that Shepherd’s “neutrality” is “kind of the problem”; it’s wrong, he explains, “bringing something like this up in class not critically.”

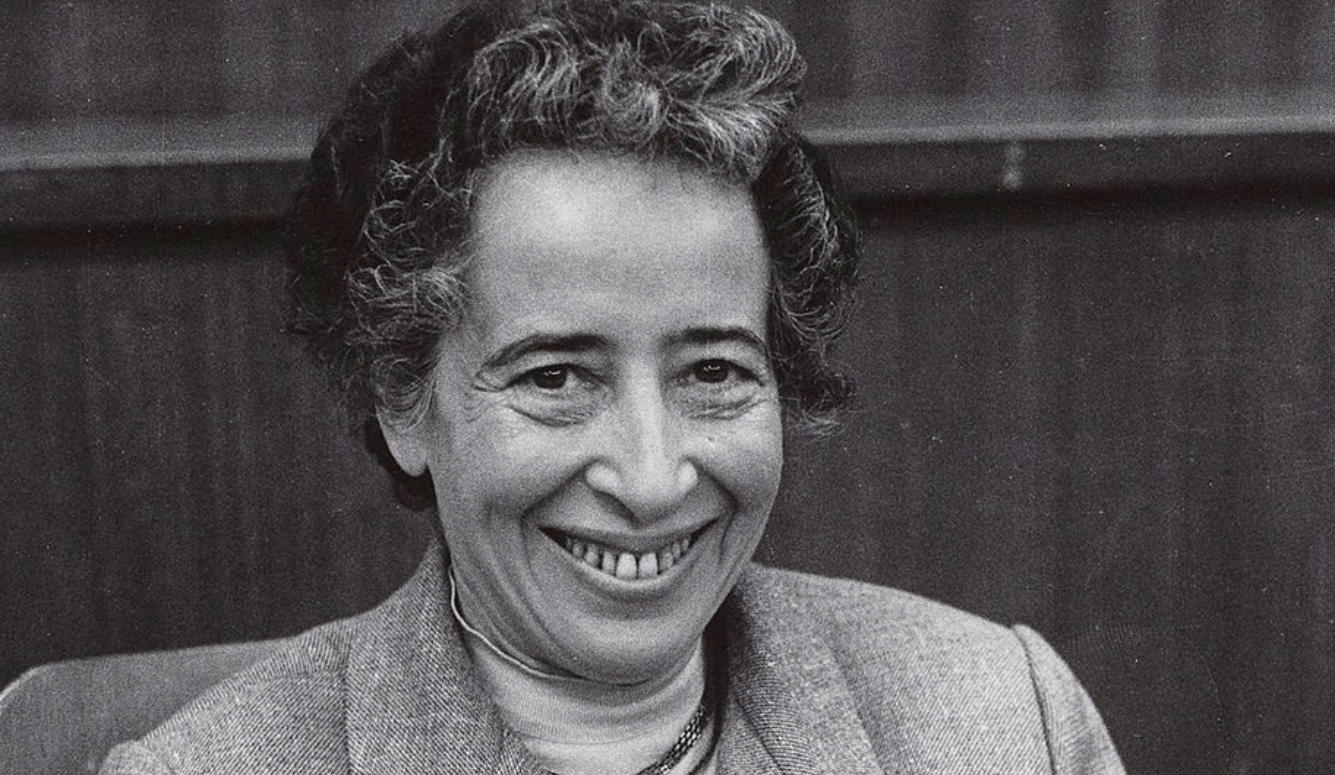

Here, his use of “critically” does not reflect the common meaning of “presenting opposite views.” Instead, it’s a reference to the leftist ideology of critical theory. Critical theory was created largely by a group of Marxist academics who started out in Germany but ended up at Columbia University. It posits groups and ideas must be presented in terms of the oppressed and the oppressor with the position of the former being elevated and that of the latter being muted or silenced completely.

That his notion of what constitutes “critical” differs from most people’s becomes clear when he openly refutes Shepherd’s claim that the purpose of “university is to challenge ideas you already have” in the neutral spirit of open, two-sided, debate. Rambukkana says that some ideas are not “up for debate” and that the proper way to approach certain views is to tell students, “this is a problematic idea that we might want to unpack.” When pressed by Shepherd if this form of contextualization isn’t tantamount to “taking sides”, Rambukkana, unphased, responds, “Yes.”

In one last plea to reason, Shepherd asks if it does not demean the intelligence of university students to believe that they must be told how to think about an issue because, after all, they are “adults.”

Rambukkana replies, “Yes, but they’re very young adults. They don’t have the critical toolkit to be able to pick it apart yet. This is one of the things we’re teaching them, so this is why it becomes something that has to be done with a bit more care.”

Rambukkana’s insinuation that “teaching” equals indoctrinating summarizes how “the appeal to contextualization” works. But I’ll “unpack” it a bit further.

As the dialogue between Shepherd and Rambukkana shows, this strategy is simply a version of “leading the witness” or “priming the candidate.” In a court room setting, leading the witness is an illegal practice in which an attorney presents information in a biased way to elicit the right responses from a witness on the stand. Similarly, in an academic setting, priming the candidate occurs when a researcher asks certain questions, or shows particular images, in order to motivate specific thoughts or responses in a human subject. In both cases, an authority figure is putting words or ideas into the mouth or mind of someone under their control.

While they try to give it a coat of respectability, “leading” and “priming” is exactly what those promoting “the appeal to contextualization” strategy believe should happen in the classroom.

As I’ve said, Rambukkana introduced the “appeal to contextualization” but increasingly it’s found in the latest open letters and op-eds crafted by Laurier’s free expression opponents.

In an open letter to the student body issued November 28th, the presidents of Laurier’s undergraduate and graduate student unions issued a joint statement calling for “proper contextualization and intentional facilitation by instructors” to ensure “challenging material should not willfully incite hatred or violence.” We should probably keep in mind that their point of reference when they mention “challenging material” that “willfully incites hatred or violence” is the showing of a four minute clip from public television.

Similarly, in a national op-ed published December 5th, one of Laurier’s sociology professors threw her support behind “the appeal to contextualization” describing what enlightened censorship looks like in her class. She wrote:

When I show videos of controversial speakers like [Jordan] Peterson and Anne [sic] Coulter in my classes, it is within a critical context where students can deliberate on the boundaries between free speech, hate speech and human rights in a democratic society based on social justice ideals.

I don’t think I’m misinterpreting when I repackage this professor’s classroom ground rules as: we can discuss controversial speakers but only within a critical [theory] context [of oppressed and oppressor] that judges the speakers on [my] social justice ideals.

Of course, this begs the question, what happens if students in her class don’t play by the ground rules? That is, what if they have an opinion that’s at odds with critical theory or some of the more radical ideas of social justice?

Sadly, we know what happens. Students challenging concepts such as white privilege—regardless of their intent or the quantity or quality of their facts—are labeled racists, those debunking the gender wage gap are labeled misogynists, and those giving equal time to an argument opposing compelled pronouns are labeled “transphobic.” (Again, “transphobic” is the actual label university representative Adria Joel used to describe Shepherd despite her insistence that, ““I know in my heart, and I expressed to the class, that I’m not transphobic.”)

Next, after receiving their obligatory label, these non-conforming students will be accused of spreading hate speech. Besides Shepherd’s case at Laurier, a quick Google search provides scores of examples from of universities where this has also happened. Then comes the final step in the process whereby those making the accusation of hate speech will say they now have the right to shut down their ideological opponents.

To be sure, my Laurier colleague says as much when, in the same op-ed, she writes:

As an academic, I support free speech as well as academic freedom. But these are not without limitations. Freedom of expression is limited by the consequences of that speech. Spreading hate is not free speech.

It doesn’t matter to these free speech foes that their interpretation of what constitutes hate speech is completely at odds with the facts. I imagine that they rationalize their “noble lie” because the ends justify the means. But they willingly ignore that in the history Canada no one has ever been convicted of hate speech for statements that use civil language, are absent threats or incitement of physical violence, and reflect fair comment or factual evidence. While there are moves from those on the far-left to change the current legal status-quo, it’s currently the law of the land that Canadians are free to challenge and criticize any idea, person, or group provided they adhere to the criteria I’ve described.

The Appeal to Common Sense

The bulk of my essay has explored how political language has been used by a significant group of professors and students at Wilfrid Laurier University to craft two appeals meant to stifle free speech. In keeping with the theme of this essay, I’ll conclude with a final appeal of my own—an appeal to common sense. I’m making this pitch to those on my campus who feel restrictions on free expression and inquiry—beyond the bounds of Canada’s current laws—are needed.

To my faculty colleagues, in particular, I say: Please reflect on the history of the marginalized people and groups that you’re seeking to protect through your calls for enlightened censorship. Consider how it is that they now enjoy the enshrined rights they do. If you’re honest, you’ll admit that the single greatest factor in their collective advancement has been the ability to articulate their arguments freely.

In light of that evidence alone, it’s absurd to think that restricting free expression at this time will come to any lasting good.

Mind you, it was George Orwell who said there are some ideas so absurd that only an intellectual could believe them: “no ordinary man could be such a fool.”