History

The Problems of “Privilege”: Lessons from the French Revolution

It has almost been forgotten that the concept of privilege, and critiques of privilege as the source of society’s ills, are nothing new in history.

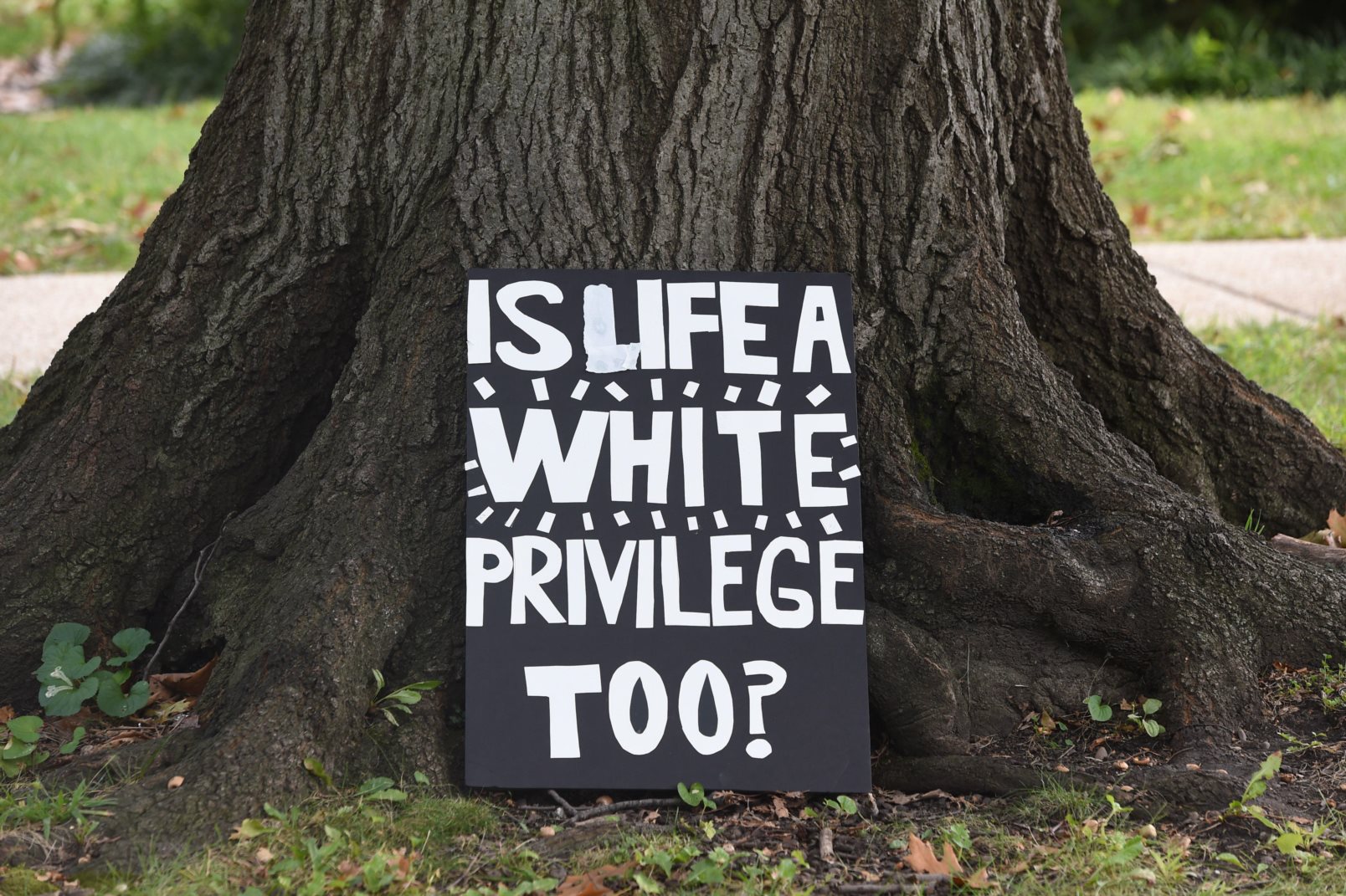

In recent years, ‘privilege’ has become an important concept in modern politics, academia, and popular culture. It appears in an increasing and disorienting number of forms, from male privilege and white privilege, to “gay privilege,” “black male privilege,” and “family privilege,” and these claims about privilege animate a wide array of political stances. Supporters of Hillary Clinton criticized voters for Bernie Sanders and Jill Stein as privileged radicals risking a Trump victory for the sake of inflexible principles. Supporters of the latter candidates returned fire, targeting Hillary voters as privileged centrists out of touch with America’s economic and racial inequalities. Donald Trump, of course, as countless media outlets insist, is (white, male) privilege personnifed; his supporters, meanwhile, are said to demonstrate the extent of their own privilege by denying that privilege exists. In the classroom and in the media, people are increasingly asked (or made) to measure, acknowledge, and strive to reduce their privilege. “Privilege studies” is a growing field, with more and more scholar-activists devoting themselves to its practice.

In the midst of all this discussion of privilege, it has almost been forgotten that the concept of privilege, and critiques of privilege as the source of society’s ills, are nothing new in history. The current focus on privilege among academics and activists grew largely out of the work of Peggy McIntosh in the late 1980s. Yet for most of the late medieval and early modern era, Europeans understood privilege to be the basis of political, economic, and social life. The first attacks on privilege appeared in the years before the French Revolution, and these critiques inspired many of the Revolution’s transformations. This neglected history of ‘privilege’ as a polemical concept offers sobering warnings for the present.

‘Privilege’ is derived from the Latin words for ‘private’ (privus) and ‘law’ (lex); in the Roman legal system, and in the medieval European traditions derived from it, a privilege was conferred by a special law concerning a single individual, corporate body, or community. Originally understood as exceptions to general legal principles, privileges gradually became part of the organizing structure of European societies. In the medieval and early modern eras, Europeans imagined themselves, not as citizens of their states equal to all other such citizens, but as members of different groups with specific rights, duties, and privileges attached to their various legally defined identities.

A man might belong to the local shoemaker’s guild, the members of which had the exclusive privilege to make and sell shoes, jealously barring all others from this line of work. A woman might belong to the corporation of market women, who alone enjoyed the privilege to sell retail goods in the city square. Authors and booksellers had to seek a ‘privilege’ each time they wanted to print a new book. The ability to make shoes, sell goods, or print books was a privilege because it was something specially granted by the king to a distinct group of people; no one had the right to do such things merely as an individual with ‘natural rights.’

The best privileges, naturally, went to social elites. Kings granted wealthy investors the privilege of controlling lucrative state monopolies. Entire sectors of the economy, like trade with Asia, were handed over to such privileged groups as the East India Company. Members of the nobility were particularly privileged, enjoying such benefits as exemptions from taxes or the right to be tried in court only by fellow nobles. But while nobles might have possessed the most power and wealth, the fact that they were privileged was not what separated them from other members of society. Before the French Revolution, almost everyone in European societies, from cobblers to counts, made their livings and made sense of themselves through a dense network of privileges, large and small.

By the eighteenth century, a social order composed of various communities and individuals each possessing specific gradations of exemptions, exceptions, and extraordinary rights began to seem intolerably confused and unjust to some self-consciously ‘enlightened’ intellectuals. French thinkers, in particular, turned against privilege, seeing it as the source of many of their country’s problems. France’s economic backwardness compared to Britain or the Netherlands seemed to be the fault of privileged guilds stifling innovation. The burdens and inefficiencies of France’s tax system seemed to be the fault of privileged nobles not paying their fair share. And indeed, wasn’t the hereditary monarchy itself, with its lavish expenditures on palaces and wars, the ultimate expression of the danger of privileging some people over others?

One of the first systematic attacks of prejudice appeared in Denis Diderot and Jean d’Alembert’s famous Encyclopaedia. A sprawling work, the publication of which ran to multiple volumes and editions spanning the years 1751-1772, the Encyclopaedia was a landmark text of the Enlightenment. It not only contained up-to-date knowledge on a staggering variety of topics, but also filtered into its articles radical critiques of the nobility, monarchy, and social system of pre-revolutionary Europe. The entry “Privilege,” written by Diderot, described its topic as “an advantage given to one person over another. The only legitimate privileges are those given by nature itself. All others can be seen as injustices against everyone in favor of a single person.” Cheekily, Diderot filed this incendiary political sketch under the heading of “Grammar.”

The suggestion that French society should be transformed through the elimination of privilege might have remained only a daring idea aired in philosophical debates, had the debt-ridden French monarchy not stumbled into a desperate crisis in the late 1780s. Previous attempts by the monarchy to push through reforms of the French judicial and economic systems had been stymied by traditional institutions representing the interests of the nobility. Now, as reform seemed more urgent than ever, many were ready for radical solutions. In 1789, as crowds stormed the Bastille, and as non-noble elites proclaimed themselves to be a ‘national assembly,’ the previously obscure cleric Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès placed himself in the center of French politics with an essay singling out privilege as the cause of France’s woes.

This essay, What is the Third Estate?, came to be seen by many revolutionary politicians as a justification and elucidation of their own inchoate demands. Sieyès himself became one of the most prominent figures of the revolutionary decade of the 1790s, and saw many of his ideas put into action. In What is the Third Estate?, Sieyès condemned France’s ‘Estates system,’ by which people were identified as clergy (First Estate), nobles (Second Estate), or the rest: the vast majority of the population (Third Estate). He called for a new kind of society in which elites would be chosen not on the basis of their bloodline, but on the basis of ability and merit. People like himself—smart, ambitious men from comfortable but non-aristocratic backgrounds—should make the decisions that mattered.

Sieyès’s argument hinged on a polemical reinterpretation of privilege. Ignoring the fact that nearly everyone in French society possessed some form of privilege, he insisted that the nobility and religious elites were the “privileged order.” Under the monarchy, privileges were necessary even for such humble tasks as running a market stall, and being a member of society at all meant being a part of one privileged group or another. Yet Sieyès argued that “a privileged class is dangerous … by its very existence” to the rest of society. Denying that the Third Estate had privilege, he claimed that it, and it alone, was the real “nation,” while “everything privileged by the law in whatever way is no longer part of the common order … and thus not part of the Third Estate.” The “privileged order” of nobles was not even part of France, but a foreign menace, a parasite. By “removing” it, Sieyès insisted, “the nation would not be something less but something more.”

The decades before the French Revolution had not been a time of increasing disparities between nobles and non-nobles. Indeed, historians today insist that the nobility was quite open, with wealthy non-nobles buying their way in, and with social and legal barriers between noble and non-noble elites fading into irrelevance. The monarchy was increasingly tolerant of religious minorities like Protestants and Jews, and eager to promote what it thought were enlightened reforms. But even though privilege was widely distributed throughout French society, and the nobility was far less powerful and oppressive than it had been in previous centuries, it was at this moment that ‘progressive’ voices like that of Sieyès could wield the concept of privilege as a political weapon, marking the ‘privileged class’ for destruction.

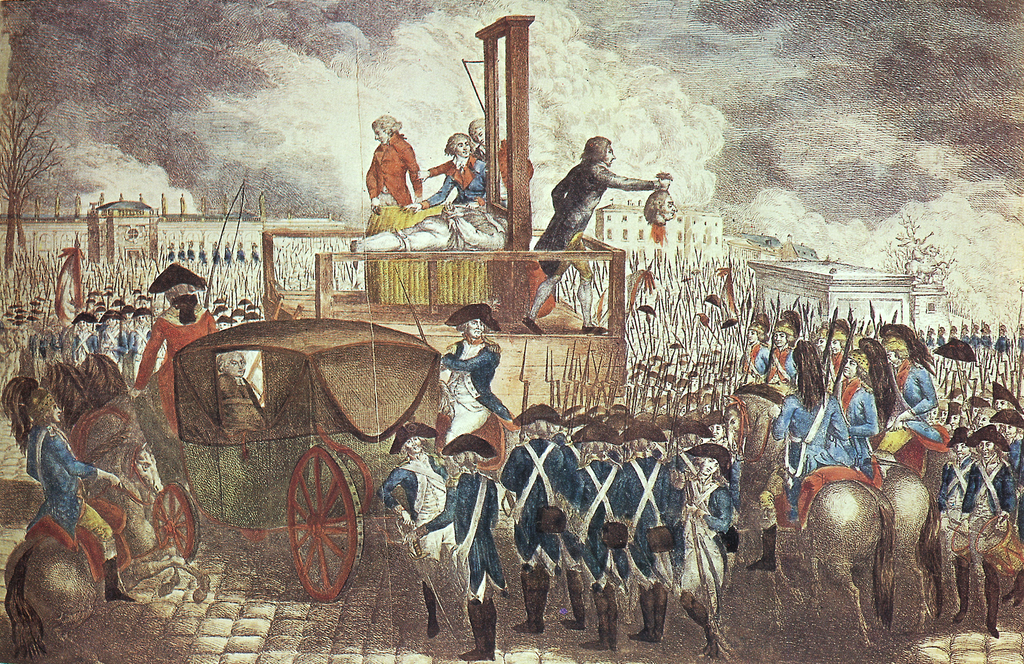

What is the Third Estate? didn’t clearly distinguish between getting rid of the nobility institutionally through political reforms, and getting rid of nobles individually through violence. On August 4, 1789, the National Assembly abolished the nobles’ privileges, and suppressed the very existence of a hereditary nobility the following year. Of the country’s tens of thousands of former nobles, some fled the country, and the majority who remained began to seem increasingly like threats to the revolutionary agenda. After France abolished the monarchy and declared war on its neighbors in 1792, former nobles went to the guillotine. The execution of thousands of them—and thousands of non-nobles suspected of harboring sympathy for what was now called the ‘Old Regime’–during the Terror had been prepared in some measure by Sieyès’s eliminationist condemnations of the privileged. After all, if nobles were by their very nature privileged outsiders hostile to French society, what could be more patriotic than getting rid of them by whatever means necessary?

The French Revolution floundered in its own blood, buffeted by coups and counter-coups, before being smothered by Napoleon. But Sieyès’s ideas went on their triumphal way, setting the tone for modern politics. Aristocratic claims to superior birth gave way to new ideologies of merit, in which individuals of any background should be able to ascend to economic and political power by virtue of hard work and intelligence. Sieyès, however, never intended merit to work for everyone. Most Frenchmen, he wrote, should be considered as little more than machines or beasts of burden working for an intellectual elite. Even if they were allowed to vote, the poor and uneducated should not be allowed to run for office. What he said about people of African origin can’t be repeated in polite company.

Although it was offered by revolutionaries as the solution to privilege, the ideology of merit has often worked in modern Europe and North America as a means of perpetuating the privilege of the powerful. Indeed, it is in some ways more insidious than the Old Regime form of privilege, insofar as it works clandestinely, disguising itself as a natural quality. When sociologists like Charles Murray argue that economic inequality results from the fact that higher-IQ people in a meritocratic society naturally earn more wealth and congregate with each other, some have wondered whether merit and intelligence aren’t just twenty-first century synonyms for noble blood. Systems formally based on merit and equality seem increasingly suspect to critics who see privilege lurking in the very structures that were designed to stamp it out. And a sense that contemporary American society is less meritocratic, and indeed systematically structured in favor of certain groups at the expense of others, motivates many critiques of privilege today.

As Sieyès’s own case shows, such critiques cannot simply be dismissed. Ironically, however, sweeping condemnations of privilege seem most plausible to political actors at moments when they least describe reality. Nobles, who had never been less powerful than in the years before the French Revolution, appeared to revolutionaries as the diabolical masters of French society. White men, who have never been relatively less powerful in the United States (or a smaller proportion of the population), appear to white liberals’ favorite expert on race as the bearers of a “glowing amulet” of privilege filled with “eldritch energies.” Sieyès’s legacy should alert us to the dangers hidden in such purple prose. Language that identifies specific groups as vectors of the supposedly dangerous, anti-social force of privilege sunders society into the good, oppressed victims and the wicked, oppressive victimizers. Everything that the former might do to the latter, by this logic, is merely self-defense. The French Revolution is a testament to the dangers of such thinking.