Top Stories

The Once and Future Liberal: After Identity Politics

Mark Lilla has written a book asserting that liberals should be more committed democrats.

A review of The Once and Future Liberal: After Identity Politics, by Mark Lilla. HarperCollins, (August 15, 2017) 160 pages.

Like Hillary Clinton, many commentators of all stripes are still looking back at the 2016 presidential election and asking: “What happened?” Mark Lilla’s short book builds on a New York Times editorial claiming liberal identity politics drove voters toward Donald Trump. The problem, Lilla tells us, isn’t just Trump’s victory. Liberals have failed to provide “an image of what our shared way of life might be”, leading to electoral failure across the board: local, state, national.

So what is “identity politics”, and who are these “liberals” who have been lost in it? It’s never made clear. “Liberal” seems to mean just “Democrat”, without any explication of what political liberalism should entail. “Identity politics”, Lilla says, is “a pseudo-politics of self-regard and increasingly narrow and exclusionary self-definition that is now cultivated in our colleges and universities.” Even those of us who aren’t fans of college students’ shenanigans might want to hear more about why or how the concerns of group identity turn into concerns of self-regard. Indeed, “identity” is the best candidate for what keeps Lilla calling himself a liberal despite being at odds with its contemporary conception.

Lilla’s own explanation of his liberalism, given by the book’s structure, is that politics is liberal by definition. Anything individualistic or libertarian is “anti-politics” (the book’s first chapter). Anything symbolic or identitarian is “pseudo-politics” (the book’s second chapter). I have critiqued this kind of argument elsewhere. One can’t draw normative conclusions from verbal disputes regarding what politics “is” or what it’s “about”; attempts to do so verge on sophistry.

Lilla clearly thinks he is making a pragmatic case, but he does not engage with any empirical political science; no numbers of any kind—polls, turnout, what have you—appear in the book. Instead, he seems to believe his thesis is self-explanatory, even self-evident: “An image for Roosevelt liberalism and the unions that supported it was that of two hands shaking. A recurring image of identity liberalism is that of a prism refracting a single beam of light into its constituent colors, producing a rainbow. This says it all.” But of course if Lilla has only written this book for people to whom “this says it all” then he is guilty of exactly the sort of tunnel vision and narrowness of scope he decries. Without knowing what his preferred liberalism really consists of, it’s hard to know how it differs from identity liberalism.

Lilla’s writing can be austere, moving, humorous; but also—well—the stuff of caps-locked comments sections. “Pseudo-politics” and “anti-politics” alike bring tirades and strange comments. He says the “job” of homeless people in college towns is “to keep it real for the residents.” In a section called “Sunset” we’re told that 1990s Republicans “began participating in the daily bacchic rites of shock radio and Fox News, whipping each other and their base into a frenzy of apocalyptic doom about the state of the country. Morning in America? No, midnight! Midnight! Midnight!” He means “talk radio” (Rush Limbaugh), not “shock radio” (Howard Stern); “sunset” doesn’t happen at “midnight”; “apocalyptic doom” is an ugly pleonasm. The frenzy, one feels, is contagious. The ends of paragraphs often bring short sentences, even fragments: “No, midnight!” “And patriotism.” “Mission accomplished.” “Donald Trump did.” “They already are.” “They got paid.” Sometimes they even come in pairs: “The results could be quite comical. But some are still standing.” This affectation is reminiscent of an over-earnest student. Obviously someone once told Lilla that such constructions help readers feel that disparate factual threads have been tied together. Find them and bring them to me.

What the book does right

Edward Hopper’s ‘Compartment C, Car 293’

Lilla grasps and communicates an impressive range of historical detail. His elaboration of the psychological neologisms of the 1950s and 1960s, for instance, tells you as much as a season of Mad Men about the anxiety underlying any given perfect family’s perfect facade. Lilla was born in 1956 and the reader gets the sense—for good and for ill—that the culture of the era is carved deeply into his cognition concerning the current political climate. The portraits of mid-century personalities are sharp, warm, evocative, and convincing: light and darkness shaded in the alienated company man, the unfulfilled housewife, the well-meaning but self-indulgent hippie. These qualities fall off as the book moves closer to the present day. Lilla should write something just on romanticism, identity, and politics in the fifties and sixties, favoring a defter touch and trusting readers to connect the dots themselves.

The discussion of colleges and universities is often superb and often funny. On “[the] whole scholastic vocabulary” of interactions between self and society—“fluidity, hybridity, intersectionality, performativity, transgressivity”—Lilla says that “[a]nyone familiar with medieval scholastic disputes over the mystery of the Holy Trinity—the original identity problem —will feel right at home.” He appreciates the way campus politics can affect electoral politics through culture. His treatment of the thoroughly terrifying phrase “Speaking as a…” is very necessary. Throughout, Lilla often exhibits the historian’s knack of finding little events, characters, and phrases which somehow contain within them the whole story of a place and time.

The book also does well to return frequently to the theme of coastal versus interior mindsets. More explicit discussion of the global phenomenon of urbanization could have been fruitful. Lilla’s lyricism in these sections belies the book’s nominal focus on strategy and tactics: he speaks of “places where Wi-Fi is nonexistent, the coffee is weak, and you will have no desire to post a photo of your dinner on Instragam. And where you’ll be eating with people who give good genuine thanks for that dinner in prayer”. This perspective is not pragmatic, but simply that of “a good liberal” who has “learned not to do that with peasants in far-off lands”. The sympathetic outlook might feature better in a book built differently. We’re taught to show, not tell; Lilla could do more for his cause by writing humanizing histories of the heartland than by inveighing against people he finds misguided. Chris Arnade does this as a journalist; his reward is mockery from the clever coastal set.

Dispensations, political and otherwise

Lilla tells roughly the following story. In the wake of the Great Depression, Franklin Delano Roosevelt offered society a “political dispensation”. Exemplified by the Four Freedoms (of speech, of worship, from want, from fear), this dispensation included a vision of citizenship: of what Americans share, what their rights are and what they owe to each other. It gave citizens a sense of common purpose, a reason to work together democratically, and a conviction that nobody deserved to be left behind; it was incompletely realized, to be sure, but also provided the tools to rectify its own gaps, as in the civil rights movement. Economic growth and technological and medical developments following World War II began to obsolete this vision. Americans became increasingly “romantic”, committed to self-expression and authenticity and disturbed by large institutions and societal traditions. This romanticism morphed from a political individualism characteristic of the New Left into the economic individualism of Ronald Reagan.

President Ronald Reagan with UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

Reagan offered an “anti-political dispensation” which Lilla sums up in four “catechisms” outlining the ethics of self-reliance; the priority of development over redistribution; the salutary effects of free markets; and, finally, “that government . . . ‘is the problem.’ . . . Government itself”. After the election of Bill Clinton, the Republican Party decayed into anti-government malarkey, while the Democrats, in a self-regarding focus on “identity”, recapitulated the old New Left’s errors. Donald Trump defeated both parties in the 2016 election, but the current situation is more dire for Democrats, whose representation in local and state government has also been gutted. What the Democrats need is a new, shared vision of citizenship.

So the book’s history is roughly generational, and not particularly novel: Baby Boomers were self-obsessed and Millennials are self-obsessed and these narcissisms interact in complex ways. The central political thrust of the book is that liberals need a new Roosevelt/Reagan-style political dispensation. What’s a political dispensation? It’s “a difficult thing to define, and difficult even to perceive . . . choose your metaphor.” Okay: so they’re just fuzzy framing devices for this text. Where do they come from? “Every revolution has material preconditions.” Some preconditions of the Reagan Dispensation included “public policies encouraging home and car ownership”, “no-fault divorce”, “legalized abortion”. These hardly seem material in the strictest sense; quite the opposite: these are political preconditions. But this should make us wonder how large the dispensation’s effect really was.

The book’s third chapter tries to give us a few lessons for dispensation-production. Three are “priorities”: “institutional over movement politics”, “democratic persuasion over aimless self-expression”, and “citizenship over group or personal identity”. A fourth is broader: we have an “urgent need for civic education in an increasingly individualistic and atomized nation”. Lilla goes on to say that the rhetorical device of citizenship can play a crucial role in structuring a liberal response to these lessons: it contains within it, in a way, all four. Just why would a dispensation of citizenship be expected to appeal to the voters allegedly left behind by the Democratic Party? The old dispensations grew out of those (partly political) “material conditions”; no analysis is offered of which current material conditions might be relevant to this new dispensation’s development.

Institutions, democratic and otherwise

Lilla stresses that “the main focal point of American democratic politics is and always has been: government.” He applies this contention like an axiom: democratic if and only if institutional. “Courts” and “bureaucracies” are counted as democratic alongside “executive offices” and “legislatures.” Mass movements, by contrast, are denigrated. But courts and bureaucracies actually uphold important values in tension with democratic values. Lilla does allow that the courts have played an overlarge and destructive role in Democratic politics. Liberals have eagerly made policy, from abortion to gay marriage, by appellate litigation rather than by legislation; this, Lilla says, has given insiders the impression that all their political stances are matters of inviolable right and outsiders the impression that liberals are uninterested in public debate and persuasion. This should have been discussed at further length. And Lilla seems unwilling to treat this as an actually anti-democratic strategy; he instead focuses on how it looks like one. But it’s not just “the public” that sees it that way. Lilla writes as though he’s never read a Scalia dissent. He also avoids acknowledging how successful legislation by litigation has been. Many liberal victories of the past half-century came in court. The “right-leaning Supreme Court” which Lilla says “stymied” the Clinton and Obama presidencies supported abortion, affirmative action, Obamacare, and gay marriage. As for the administrative state, the “fourth branch” of our government, the notion that insulated, careerist technocrats are closer to democracy than popular movements is just odd.

As his “anti-politics” and “pseudo-politics” designations suggest, Lilla seems to judge whether or not some institution is democratic in part by who controls it. Increased involvement of legislators in judicial nominations is “partisan[ship]” rather than democracy. He writes that “[y]ou would never think to listen to [Republicans] that we live in a democratic system where we get to elect representatives” but then, just pages later, that “Americans have been spectators at the dark comedy of Republicans running for office successfully against ‘the government’”. If our system is so incontrovertibly democratic then we cannot possibly just be “spectators”. Of Trump voters he writes: “Given his manifest unfitness for higher office, a vote for Trump was a betrayal of citizenship, not an exercise of it. . . . Wanting to shake things up and leave it at that is not a democratic impulse”. So the movements and parties Lilla doesn’t like aren’t really politics, and the votes and impulses Lilla doesn’t like aren’t really democratic. Q.E.D.!

Really, political dispensations themselves seem anti-democratic. They’re “revolutions” that come from above and restructure citizens’ views of their relations with one another, forming popular consensus rather than being formed by it. Lilla does seem to dimly perceive the conflict; he says “romantics” might see institutional politics as “undemocratic”. That the term might have multiple senses or meanings merits no discussion. In a similar internal confusion he “remind[s] the identity conscious” that “[e]lections are not prayer meetings”. Tough talk from a guy whose whole book is about “dispensations” and “catechisms”.

Identity, narcissistic and otherwise

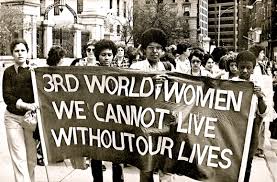

Lilla’s story places a lot of importance on “identity” and his association of it with self-regard. For instance, he interprets the sixties slogan “the personal is political” as an instance of “political romanticism”, expressive of “the urgent need to reconcile self and world” either by “flee[ing] so as to remain an authentic, autonomous self” or by “transform[ing] society so that it seems like an extension of the self. . . . where the answers to the questions Who am I? and What are we? are exactly the same.” This interpretation is highly counterintuitive. In her 1970 essay “The Personal is Political”, Carol Hanisch wrote: “There are no personal solutions at this time. There is only collective action for a collective solution.” This more plausibly demands a sublimation of the individual to the (e.g. disenfranchised, disadvantaged) group. Part of the phrase’s legacy is the “problematic fave”: a book, movie, or other cultural product that one feels, on political grounds, guilty for enjoying.

The Combahee River Collective

Some participants in the sixties New Left called for greater demographic diversity in its leadership. Lilla concludes that those who complained “wanted there to be no space between what they felt inside and what they did out in the world. . . . And they wanted their self-definition to be recognized.” Whatever one thinks of them, the link between calls for representation within a political movement and romantic attempts at self-expression is tenuous at best. Lilla cites the Combahee River Collective’s 1977 manifesto stating that “the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity.” His understanding should be tempered by an examination of the humiliating and often self-abnegating demands placed on “allies” in identity movements. Many—most!—of the adherents of these movements’ ideologies aren’t “romantics” at all; they’ve been browbeaten by constant accusations of racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and so on. They say things like “My role in this movement is to shut up.” Not exactly Ralph Waldo Emerson there.

The “self-regard” frame also obscures some of identity politics’ worst faults. Lilla suggests that “a recognizable campus type drawn to political questions” will be taught such that “those issues that don’t touch on her identity are not even perceived.” Actually, today’s “recognizable campus types” proselytize a bowdlerization of a sociological anti-theory called intersectionality. In this current form, intersectionality dictates that all identitarian struggles are actually the same; the enemy is always and everywhere simultaneously white supremacy, patriarchy, heteronormativity, neoliberalism, capitalism, imperialism and so on. This is how Israeli flags get banned from gay pride parades. Now it could be that, in some sense, these “campus types” appropriate other struggles in order to enhance their self-image in some way or another. I wouldn’t know, and Lilla doesn’t make such an argument.

There is, however, a really important way in which campus-style identity politics is self-regarding. One of its ultimate goals is the personal expiation of historical sins like slavery through “working on” one’s own “unconscious biases” (and so forth). This matches up with the contexts in which such ideas are most strongly felt in the lives of average students and white-collar workers: hostile workplace training seminars; microaggression workshops; first-year orientations where well-paid diversity consultants revel in the tears of struggling suburbanites who are hearing for the first time that they are oppressors just in virtue of being themselves. This personal focus is in stark tension with the claims of high-minded identitarians to be addressing “systemic” or “structural” issues. But Lilla is unable to plumb the depths of this tension; stuck in the battles of the sixties, he understands neither what identitarians are trying to accomplish nor how they’ve failed to accomplish it. Talk of “purity”, and of what Lilla calls “the social justice warrior” as “a social type with quixotic features whose self-image depends on being unstained by compromise”, seems immature and unsympathetic. Even Disney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame was able to recognize that guilt and self-loathing often silently underpin the spoken conviction that others are going to hell. With the “social type” in question, it’s not silent. They happily say that they, too, are racists, misogynists, and phobes of various sorts who often can’t help propping up an invisible and infinitely unjust system. To fail to recognize this is to fail to appreciate the scope of the pathology and the way it damages those inside the ideology more than those outside.

Tactical dispute, political disputes, epistemic disputes

The Once and Future Liberal takes itself to be a book about a pragmatic dispute within “liberalism”, but Lilla’s own diagnosis of individualism and self-regard in the contemporary American political situation should make us wonder whether there’s a substantive political liberalism he and the identitarians share. It is certainly true that many people who are involved in politics are more committed to their metapolitics or their political tactics than they are to most of their actual political stances. (We could even mock up some metapolitical tribes, criss-crossing the political ones: the violent, with neo-Nazis and anti-fascists; the victims, with Tumblr snowflakes, men’s rights activists, and “white genocide” types; and the verbose, with Lilla, me, socialist journals, and alt-right YouTubers alike.)

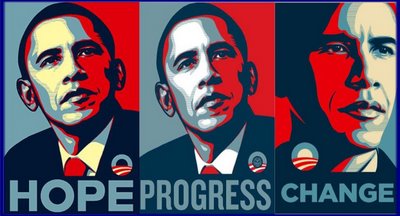

But the avoidance of substantive politics is taken too far in this little book. It neglects the Sanders candidacy, single-payer health care, universal basic income proposals. Such topics, in fact, complicate the picture immensely: the “movement politics” types on the left, though not immune to identitarian nonsense, nonetheless frequently prefer politicians like Bernie Sanders over politicians like Kamala Harris or Cory Booker. Lilla writes that Barack Obama “was not perceived to be a triangulator . . . on the far left” but “failed to conjure up memorable images of America’s past and future”. Perhaps his “far left” is MSNBC or The New Republic. Most leftists I know were highly ambivalent about Obama. An ideological centrist and about as big a fan of compromise for the sake of compromise as there’s ever been, he disappointed them by replicating Romneycare instead of aiming for something more radical. He maddened them by his association with “neoliberal” economists like Larry Summers and Austan Goolsbee and his close friend and former Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel who was considered both a cause and a coverer-up of police violence in the city of Chicago. On the other hand, the idea that Obama didn’t conjure up images of America’s future is extraordinarily strange.

The Barack Obama “Hope” poster is an image of Barack Obama designed by artist Shepard Fairey, which was widely described as iconic and came to represent his 2008 presidential campaign. Other versions used the words “change” and “progress”.

Lilla’s thesis is that the lack of a new dispensation has made it difficult for Democrats to win local elections and maintain power in Congress, but in Obama’s case the most plausible critique seems to be the opposite: that the party focused on his soaring rhetoric and forgot about day-to-day necessities on smaller scales.

When it comes to the right, Lilla at least recognizes political differences, but his framework makes them feel cultural. We hear very little about terrorism and immigration. In a book ostensibly about the relationship between identity politics and Republican electoral success, they deserve not just mention but extended analysis. Lilla believes citizenship is the rhetorical concept Democrats need right now. But of course emphasizing citizenship leaves Trumpian policies like the border wall and the Muslim ban untouched. Which is precisely the point of Trump’s supporters! We hear very little about the vast demographic changes the country is undergoing, about the glut of (rightly or wrongly) breathless news stories heralding the proportional reduction of white people in America. Again, in a book like this, that topic seems almost required for full credit. Is the Democrats’ “demographic strategy” promising? Will Hispanic voters turn Texas blue? Would a black Democratic candidate have defeated Trump due to better turnout? To hold to his pragmatic anti-identitarian thesis Lilla must believe the answer is no, but we never hear why.

In neither encounter does Lilla seem to account for the possibility that part of what makes “dispensations” work politically is whether they work, period. It could be the case that the world has largely proven American conservatives and libertarians correct when it comes to the power of markets, and more generally of decentralized individual judgments organized in a competitive manner, to aggregate all kinds of information. And it could be the case that the world has largely proven left-of-Lilla liberals correct when it comes to the blind spots of markets, to the need for robust social safety nets, to the nature and pervasiveness of injustice, to the importance of symbols, and so on. This sort of thing can’t be elided into “material conditions”. Material conditions are themselves affected by politics and the fact that the public’s judgments about “dispensations” are largely matters of emotion does not provide good evidence that those judgments fail to aim at the truth, in one way or another. Here, Mark Lilla has written a book asserting that liberals should be more committed democrats, but he leaves us wondering whether, and why, he himself fits either label.