Art and Culture

Trump's Warsaw Speech: Defending the West or Defending Illiberalism?

Donald Trump’s first major speech in Europe reminds me of the old Jewish joke in which two men ask a rabbi to resolve a dispute.

· 8 min read

Keep reading

Podcast #320: Fighting for Freedom in Iran

Quillette, Roya Hakakian

· 2 min read

The Strange Case of Alaa Abd El-Fattah

Guy Baldwin

· 9 min read

Podcast #319: How to Think Like a Human

David Weitzner, Quillette

· 1 min read

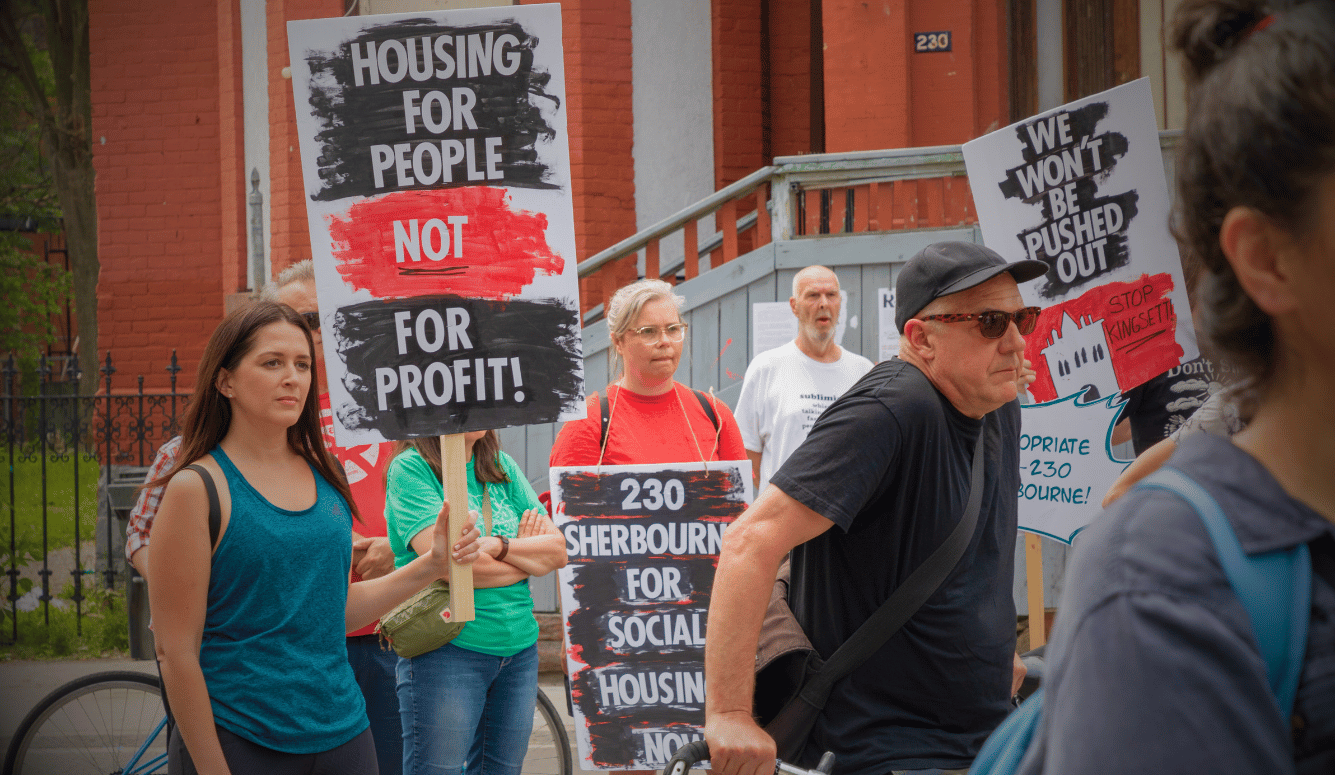

The Housing Crisis

Joel Kotkin

· 17 min read

AI and the End of Common Culture

Samuel Fitoussi

· 6 min read