Art and Culture

What Philosophers Must Learn from the Transracialism Meltdown

For years we have been hearing that political correctness is cresting, that this-or-that campus outrage represents the last straw, the turning point.

“Reserve your right to think, for even to think wrongly is better than not to think at all”

― Theon, father of Hypatia of Alexandria (Quoted in Little Journeys to the Homes of Great Teachers by Elbert Hubbard)

For years we have been hearing that political correctness is cresting, that this-or-that campus outrage represents the last straw, the turning point. Each time, however, political correctness not only does not decline, but actually gains ground. Again and again, those who prophesy the imminent decline of political correctness are exposed as false prophets. Now we hear that the Hypatia kerfuffle will be remembered as the moment at which academic philosophers finally turned against the excesses of identity politics. Whether or not this is so depends upon whether philosophers seize the opportunity to challenge the dogmas that made it possible.

The Hypatia Affair

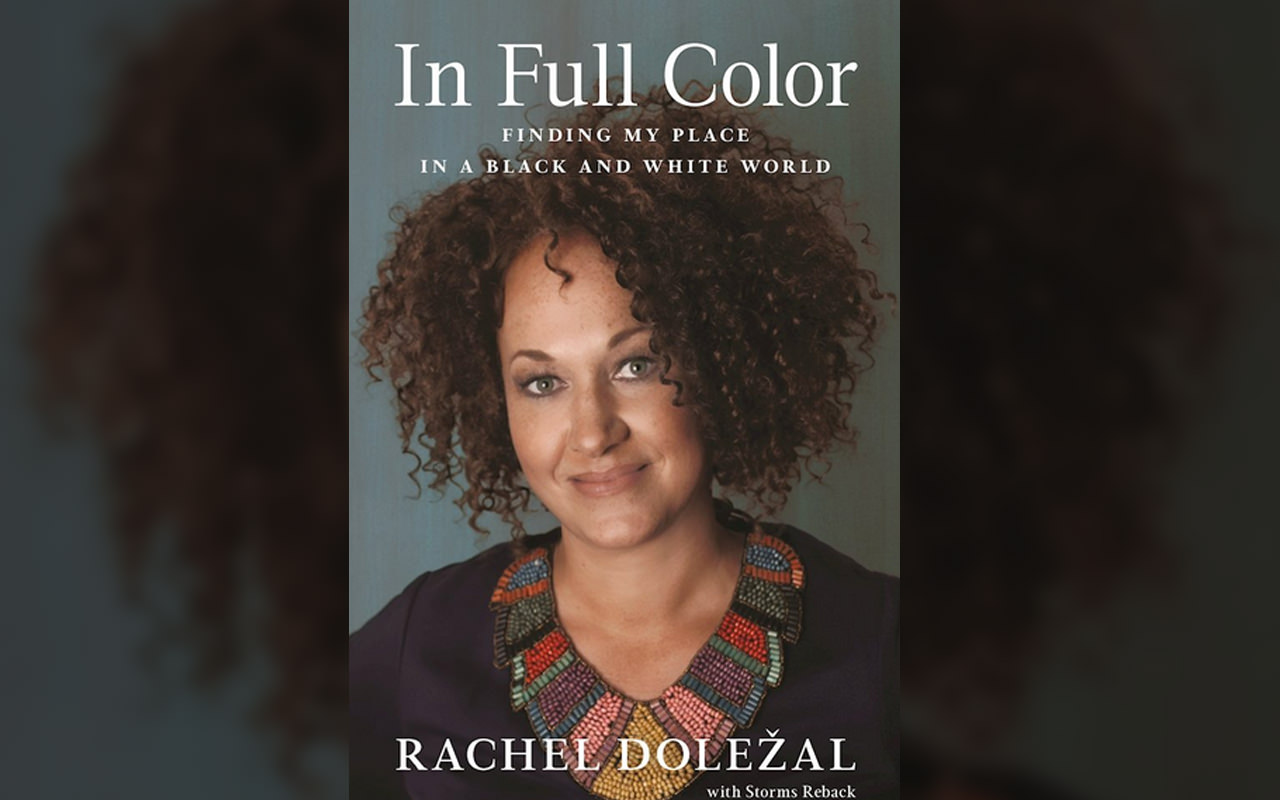

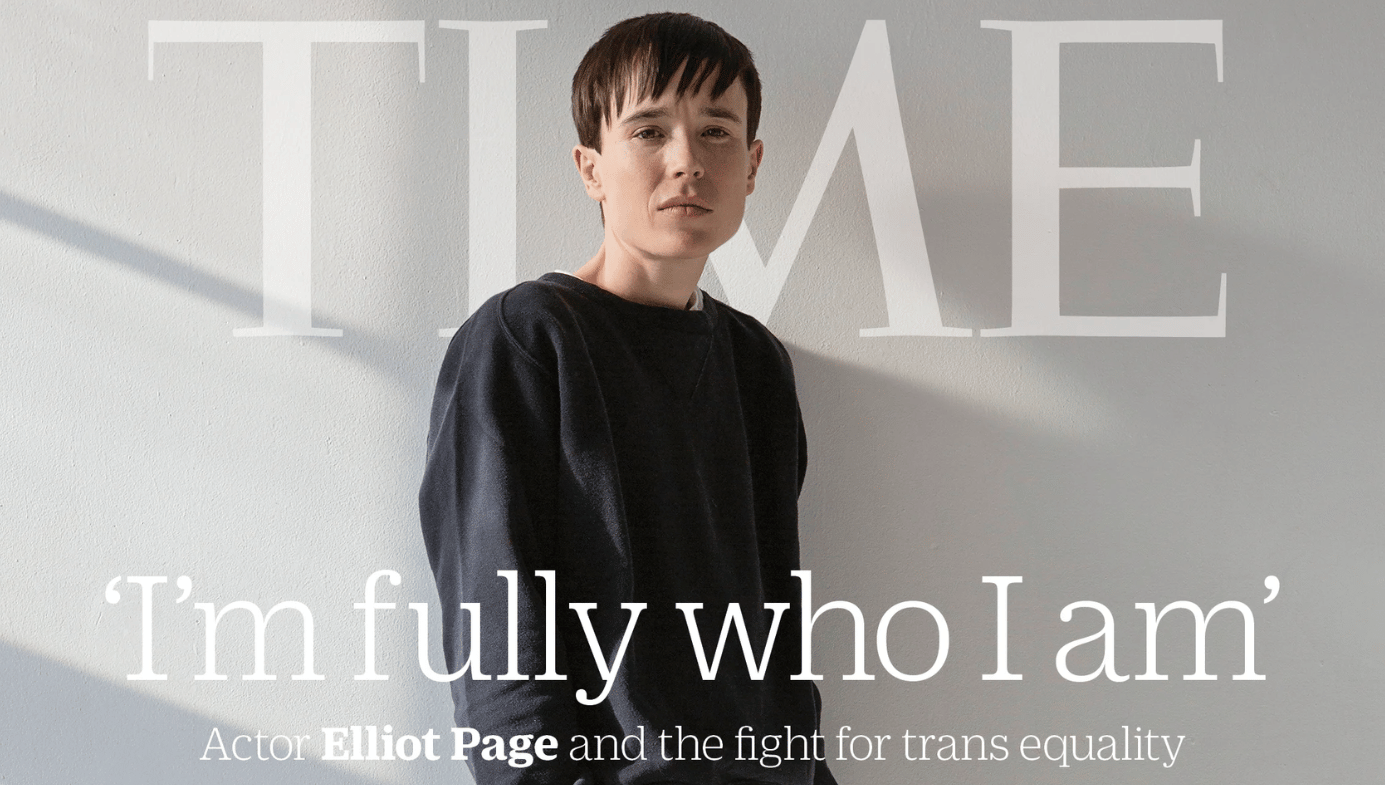

In its most recent issue (Spring 2017), the feminist philosophy journal Hypatia published an article by Rebecca Tuvel entitled “In Defense of Transracialism.” Tuvel, an untenured philosopher at Rhodes College in Memphis, Tennessee, argues that “considerations that support transgenderism extend to transracialism.” Nearly all feminists now embrace transgender identification, and yet most are skeptical, to say the least, of inter-racial transition. After exploring a number of seemingly dis-analogous features between the two, Tuvel concludes that “society should accept such an individual’s decision to change race the same way it should accept an individual’s decision to change sex.”

The article’s publication triggered an eruption of fury online. Philosopher Nora Berenstain, in a now-deleted Facebook post, asserted that “Tuvel enacts violence and perpetuates harm in numerous ways throughout her essay.” More than five hundred academics signed an open letter to the journal’s editors insisting that “the continued availability” of Tuvel’s article “causes further harm.” They demanded that Tuvel’s article be retracted, that an apology be issued for having published it, and that the journal’s review process be overhauled. In what can only be described as betrayal, two people who had been members of Tuvel’s dissertation committee added their names to the denunciation.

Philosopher Justin Weinberg, who hosts the Daily Nous blog, and Jesse Singal, who writes for the New York Magazine, each investigated the letter’s criticisms of Tuvel’s article and found them to be lacking in merit. Nonetheless, Hypatia at least partially capitulated. Cressida Heyes of the University of Alberta posted a lengthy apology on the Hypatia public Facebook page. Continuing the theme of equating words with violence, it began:

We, the members of Hypatia’s Board of Associate Editors, extend our profound apology to our friends and colleagues in feminist philosophy, especially transfeminists, queer feminists, and feminists of color, for the harms that the publication of the article on transracialism has caused.

The apology statement did not promise to retract the article, which as of this writing remains accessible at the journal’s website. But it did assert that “Clearly, [Tuvel’s] article should not have been published” and promised changes to the review process. The apology also included the not-very-reassuring assurance that the names of the two anonymous referees who recommended Tuvel’s paper be accepted would not be released. That this even had to be mentioned, as if it had to be seriously considered, should give pause to referees who would recommend publishing controversial articles.

Days later, when it was clear that a public relations disaster was unfolding, editor-in-chief Sally Scholz said that she stood behind the decision to publish Tuvel’s article. She claimed that she had not signed off on the apparently official apology statement. By the time, however, the damage had been done. Although apologists can be found on the philosophy blogosphere, the commentary and comments of the two largest academic philosophy blogs, Leiter Report and Daily Nous, indicate that most philosophers recoiled from the incident. Professor Graham Oddie of the University of Colorado, Boulder (my dissertation advisor), was quoted on Leiter Report as saying the following:

This is an attempt to silence a researcher with whom they disagree, through collective social media shaming.… It hardly needs to be pointed out (though regrettably it does) that this is an extraordinary and deeply disturbing development. Many, though thankfully not most, of the signatories [of the open letter] call themselves philosophers. This is the sort of behavior one might rather expect from the apparatchiks of an extremely repressive regime. It is just this kind of cruel, committed irrationalism that has caused the Humanities to fall disastrously into disrepute.

Why Tuvel’s Argument is a Threat

One of the more serious allegations made against Tuvel is that she “deadnamed” a trans-woman. The substance to this charge is that Tuvel in her article mentioned that Caitlyn Jenner had formerly been known as Bruce. She later apologized for this and had Caitlyn’s birth name excised from the electronic version of the article. Philosopher Mylan Engel, Jr. asks, appropriately, whether the outrage directed at Tuvel is proportionate to this or any of her other alleged infractions. Probably not, but I think I understand why her article elicited such a venomous backlash: Tuvel was an accidental subversive.

Because Tuvel assumes the truth of transgenderism, she argues primarily for the conditional, “If we should accept transgenderism, then we should accept transracialism.” This leaves an opening for some other philosopher less committed to transgenderism to “run the argument the other way.” Once a nun asked philosopher Michael Tooley what he thought about the morality of abortion. He responded deceptively by saying that it was just as wrong as infanticide. She departed satisfied that Tooley held the righteous position was that both abortion and infanticide are morally wrong. Actually, Tooley’s position is that neither are. Likewise, the equivalence of transgenderism and transracialism could be used to argue, contrary to Tuvel’s designs, for the position that neither transracialism nor transgenderism are legitimate. The latter argument goes as follows:

The Subversive Argument

- We should not accept transracialism.

- If we should accept transgenderism, then we should accept transracialism.

Therefore, we should not accept transgenderism.

Most feminists accept the first premise and Tuvel has ably defended the second premise, so the subversive argument seems to be plausible enough to deserve consideration. The person who accepts this argument is not, or at least not obviously, being unreasonable. Perhaps this reductio ad absurdum can be extended. Toward the end of the essay, Tuvel briefly considers what implications, if any, her argument has for the status of “otherkin,” people who identify as non-human animals. She insists that her argument for transracialism does not commit her to accepting transspeciesism:

[Am I committed to accepting otherkin identities?] I don’t think so. Recall my earlier point that for a successful self-identification to receive uptake from members of one’s society, at least two components are necessary. First, one has to self-identify as a member of the relevant category. Second, members of a society have to be willing to accept one’s entry into the relevant identity category. At this stage, I think it is reasonable for a society to accept someone’s decision to enter another identity category only if it is possible for that person to know what it’s like to exist and be treated as a member of category X. Absent the possibility for access to what it’s like to exist and be treated in society as a black person or as a man (or as an animal), there will be too little commonality to make the group designation meaningful. For example, if a cisgender white man fights for his rights not to be subject to anti-black police violence or to misogyny, yet never faces the possibility of having his rights so violated, we can reasonably expect allyship, not identification, from him

An initial worry about Tuvel’s response, about which I will say more shortly, is this. Tuvel concedes here that identity is contingent upon others’ acceptance. It seems to follow from that a transwoman who is unrecognized by “her” society wouldn’t really be a woman, (though perhaps because he’s being treated unjustly, he ought to be a woman). Likewise, if a racist country club excludes a prospective member because of his race, it would be true that he lacked membership, though he shouldn’t. This is a position that one might hold, but I suspect that defenders of transgender rights will insist that the unrecognized transwoman is a woman no less.

More importantly, Tuvel fails to identify any bright line separating transracialism and transgenderism on the one hand and transspeciesism on the other. Tuvel seems to say that otherkin identities can’t be legitimate because humans lack the relevant knowledge about the interior lives of animals. She does not explain how extensive the requisite knowledge must be. Some humans apparently fail to have it about other humans. It’s unclear whether this knowledge can defined so that it includes all of the transgender and transracial identity claims that Tuvel regards as legitimate and excludes all otherkin identity claims.

Therefore, if we should take Tuvel’s argument for transracialism seriously, then we should take otherkin identities seriously as well. I suspect, however, that most people would take this unpalatable consequence to be a reductio ad absurdum on transgenderism.

Puzzles about “Gender Identity”

If the central claims of the transgender rights movement were beyond reasonable doubt, then we should accept whatever consequences followed from them. But these claims rely on the notion of “gender identity,” whose nature is not straightforward. For a sustained critique, see Rebecca Reilly-Cooper’s public lecture, “Critically Examining the Doctrine of Gender Identity,” which is available on her blog, “More Radical with Age.” Reilly-Cooper observes that official definitions of gender identity reduce to the near-tautological assertion that “gender identity” is a deeply-held feeling that relates to gender. This deeply-held feeling, about which we can say very little, must be innate, universal, unalterable, and the sole determinant of gender. Suffice it to say that it’s far from obvious that any one thing really has that remarkable constellation of properties.

Gender is supposed to be a socially constructed category, and questions about what things fall into which social categories are not unilaterally decided by individuals (unless they have special standing). That is why, as Tuvel concedes elsewhere in her article, there are grounds for saying that any change in identity requires some sort of social “uptake” of other members of society. At the same time Tuvel and other defenders of transgenderism take gender identity to be radically subjective. Consider how Tuvel dismisses biological accounts of transgenderism, which she worries hold “the societal acceptance of transgenderism hostage to a biological account of sex-gender”:

First, not all trans individuals claim to have been “all along” the sex with which they now identify. This suggests that their sexed identity was not bio-psychologically determined, hormonally or otherwise. Nor do all trans people possess ambiguous biological features (hormonal, gonadal, and so on) that might suggest a different sex-gender identity lurking in the background. A bio-psychological account of transgender identity thus risks excluding these individuals.

Tuvel seems to be saying that if what trans individuals believe about their identities runs counter to the claims of “a bio-psychological account of transgender identity,” then so much the worse for that theory. She certainly gives the subjective experiences of trans individuals a lot of epistemic weight. It’s unclear whether Tuvel is criticizing “bio-psychological” accounts of transgender identity on empirical grounds (because it fails to account for the phenomena of trans experiences), on moral grounds (because not accepting the claimed identities of some people would be “exclusionary”), or some combination of both. She goes on:

Second, and most importantly, this view problematically implies that we must settle the debate over the biological versus social basis of sex-gender identity before we can know for certain whether transgenderism is a “real” phenomenon, and therefore acceptable. Not only is such a basis widely disputed, but it would be decidedly unjust for the acceptance of trans individuals to turn on such knowledge…. Rather, the biological or social basis of sex-gender identity should have no bearing whatsoever on society’s acceptance of trans individuals. (emphasis mine)

Notice how the word “real” is placed in the scare quotes. Notice, too, that Tuvel claims that it would be unjust for societal acceptance of trans individuals to turn on the answers to any questions about the nature of gender identity. That should be surprising. Do not trans individuals demand recognition on the grounds that their claimed identities are, in some sense, real and that their prior identities are in some sense artificial impositions? Can Tuvel really be saying that the truth of these claims has no bearing on society’s duty to accept transgender identities? Is it wrong to inquire into these matters at all? Moreover, how can gender identity be so radically individualistic if gender itself is socially constructed? If society creates gender, then presumably in so doing it sets limitations on how far a single person, or a small minority, can go in transgressing the constructed gender norms.

I draw two lessons from this. First, enough is puzzling about the nature of gender identity to render some central claims of the transgender movement contestable by reasonable people. Second, the correct account of transgender identity – assuming that it is a coherent notion – will almost certainly exclude the sincerely felt identities of some people. Given that this is the case, the view that most, or even all, transgender identities are illegitimate should not be unthinkable.

Conclusion

In the space of about twenty years, the claims of the transgender rights movement have gone from being so radical that they were not widely discussed, to being so orthodox, at least within academia, as to be considered beyond dispute. A standard complaint against philosophy is that philosophical debates rage for centuries or millennia without resolution. Are we to believe, then, that the many important philosophical questions about the transgender movement have been thoroughly considered and decisively settled within this short period of time? Try to locate the extensive body of philosophical literature where these issues are dispassionately discussed and decisively resolved.

In reality, a zealous minority has achieved dominance not through rational suasion, but through what I call “weaponized fragility”. Their claim to be powerless is ironically a real source of power as they go on the offence by taking offense. Philosophers would rather give wide clearance to certain topics than to risk upsetting these very powerful, very vulnerable people. The Hypatia affair is significant because it lays bare the intolerant nature of this kind of activism and the consequences of continually appeasing it. Whether or not this moment represents a turning point depends on whether philosophers are willing to recognize this, rather than treating the so-called “Hypatia affair” as an isolated incident. If philosophers want to reclaim their discipline, then they must reassert their right to ask unwelcome questions.