Art and Culture

Is It Ever Better Not to Know?

It seems that gaining more knowledge, even on topics where that knowledge could be damaging in the short term, is the preferable approach.

“What wretched doings come from the ardor of fame; the love of truth alone would never make one man attack another bitterly” –Charles Darwin, 1848 (in a letter to his friend, Joseph Hooker)

“An awful privilege, and an awful responsibility, that we should help to create the world in which posterity will live.” –William K. Clifford in The Ethics of Belief

Is it sometimes better not to know certain things? Yes, that seems obvious. Very few people would tell a religious parent on their death bed that they have decided to reject the faith their mother or father valued so deeply. We all have illusions we’d prefer to cling to, and sometimes we respect other people’s beliefs, even when we think they’re misguided, because they bring comfort or meaning to that person.

Still, we want to argue that over the long run it is better for humanity to know as much as we can about every possible question that might be asked. We think that the intrinsic beauty and instrumental benefits of the accumulated knowledge that we gain through scientific inquiry (in particular) is worth whatever adverse costs it might create in the short run.

We should start, however, with two concessions. First, we’re willing to acknowledge that in some isolated cases, one can argue convincingly that it would have been better not to know something. If a terrorist were intent on exploding a nuclear device, and needed a code to do so, we’d all be better off if they didn’t know the code.1 We want to focus not on what any given individual may or may not know at any one point in time. Rather, we want to talk about our collective, aggregated knowledge.

The second concession, which is related to the first, involves “who should know something.” We concede that in some instances not everyone needs to be privy to certain information. We collect intelligence data, for example, with the intent of organizing our actions based on information we’ve obtained without other people (or countries) knowing about it. If this information became widely known, it could jeopardize the lives of many people. We concede, then, that certain forms of tactical information are best held by highly qualified experts. It is important to note, of course, that intelligence information is not generally information about how the world works. Rather, it is specific information that is useful to know only to the extent that it helps satisfy an immediate goal, like preventing a terrorist attack.

Sometimes secrets are justifiable. But that seems only to be the case in a circumscribed sphere of knowledge. And—in the United States, at least—information remains classified for only so long before it becomes legally accessible to the average citizen and the press. This fact alone suggests an acknowledgement of certain short term risks associated with knowledge, while also admitting that over the long run we value knowledge over its absence or suppression. So, with these concessions in mind, let us further interrogate our intuition.

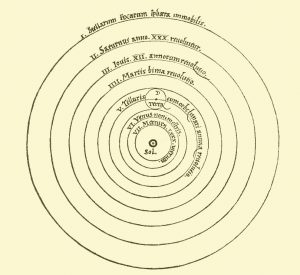

Would it be better not to know that the Earth orbits the sun? Before Copernicus revived the heliocentric hypothesis, widely accepted by ancient Greek philosophers, Europeans in Christendom could reasonably assume that they were the center of the solar system. Galileo’s observations helped rob us of this comforting myth. Clear thinking clergy at the time certainly guessed what the consequences might be. The leader of the most powerful religious organization on the planet, the Pope, felt that we would all be better off not knowing. At play was a moral calculus intended to sort out whether certain knowledge might be dangerous. In this case, it might cause people to lose their faith (or erode the power of the church, somehow). Of course, the heretics were correct about our place in the solar system. But the rumor of civilization’s great moral demise was vastly overstated.

We may have lost our centrality to the universe, but we retained our special stature as beings created in the image of the Almighty. In 1859, however, that changed too. Charles Darwin upset our intuitions in a way most people still haven’t fully grasped. Darwin understood the subversive consequences of his theory clearly, which partly explains why he waited so long to publish his book on evolution by natural selection, and why he confided to his friend Joseph Hooker that it was like “confessing to a murder” to show that species are not immutable, and that evolution is not a synonym for progress.

Human beings came to exist on this planet via the same ordinary process as every other life form—one that uses non-random selection of genetic mutation to adapt organisms to their environment. The result was eyes with blind spots, backs that are prone to wear out, and vulnerable brains that are subject to bias and defect. There is a famous quote (perhaps apocryphal) conveyed by a concerned British citizen around the time that Origins was catching fire among the public. “Surely,” she opined, “this cannot be true. Yet, if it is true, let us hope it does not become widely known.”

Darwin’s “dangerous idea” stood poised to strip us of our specialness. How could one not slip into a posture of defiant nihilism? If we’re all mere animals, what would become of our morality? As it turned out, Darwin was right. We are products of natural selection. And that fact has become widely known (if still hotly debated in some religious circles). The critics too, were right, sadly. Human morality spiralled out of control. We now live in our own filth. We rape, pillage, and steal to our heart’s desire. Why not? These things are natural, we’re products of nature; surely this is our depraved birthright?

Of course, that last part is patently false. Crime rates have fallen; diseases have been eradicated; and medical care has never been better or more widely available. Knowledge about our evolution was not our undoing. If human welfare has steadily improved over the course of history, why are we (especially intellectuals) often so pessimistic about the future? Regardless of the causes, it is because we experience this impending sense of doom that we guard ourselves against “dangerous knowledge.” Pandora’s box, and the forbidden fruit in Genesis, both belie a human worry about the consequences of knowing too much. Yet, as we mentioned, by every conceivable indicator of wellbeing—including health, lifespan, poverty, violence, crime, war, and the advancement of human rights—life on the planet has improved dramatically over long stretches of time. The Oxford researcher Max Roser has compiled much of the relevant data on these topics and made it freely available. Anyone can examine the evidence that there has never been a better time to be alive in the history of our planet.

No one would argue, though, that our understanding of the world and its inhabitants has diminished since our arrival. These two facts mean either that 1) our increased knowledge has improved human existence on this planet, so it’s better to encourage the accumulation of knowledge, or 2) knowledge is unrelated to wellbeing, which is unlikely, but if it’s true then we still have nothing to fear from learning everything we can about the world, or 3) that the world would be even better without knowledge accumulated from the science and philosophy birthed prior to and during The Enlightenment. The first two possibilities should reassure us, and the third violently strains credulity.

It seems that gaining more knowledge, even on topics where that knowledge could be damaging in the short term, is the preferable approach. But what is to be said to counter the charge that we’re being naively hopeful? David Deutsch, in his book The Beginning of Infinity, deals with this issue by invoking the tragedy that befell the Titanic on its maiden voyage. The general thrust of the point has to do with the safety of what we currently know, and why pushing the boundaries of knowledge might constitute an unnecessary risk. Yet, this intuition too, is flawed because as Deutsch notes: “It assumes that unforeseen disastrous consequences cannot follow from existing knowledge too (or, rather, from existing ignorance).” He continues: “The harm that can flow from any innovation that does not destroy the growth of knowledge is always finite; the good can be unlimited.” We concur.

As we write this, insights about physics have enabled North Korea’s dictator to threaten its perceived enemies with nuclear weapons. He is likely to fail, but even if he succeeds in causing massive harm, it’s difficult to believe that understanding how the universe works at an atomic level, and harnessing that power to create everything from powerful computers to electron microscopes, will inevitably lead to net harm in the long-run. As Deutsch eloquently reminds us:

From the least parochial perspectives available to us, people are the most significant entities in the cosmic scheme of things. They are not ‘supported’ by their environments, but support themselves by creating knowledge. Once they have suitable knowledge (essentially, the knowledge of the Enlightenment), they are capable of sparking unlimited further progress.

We should not be afraid of what we might learn and we should not prevent earnest scientists from seeking out all forms of knowledge. We can openly study the most incendiary of topics—stem cell research, cloning, artificial intelligence, sex and race differences—all the while implementing strategies for preventing its misuse for morally repugnant ends. We should embrace knowledge for what it is; our best mechanism—flawed as it might be—for shaping a better future.

Endnotes

[1] We’re grateful to a colleague who provided this example when reviewing a prior draft of the essay.