Education

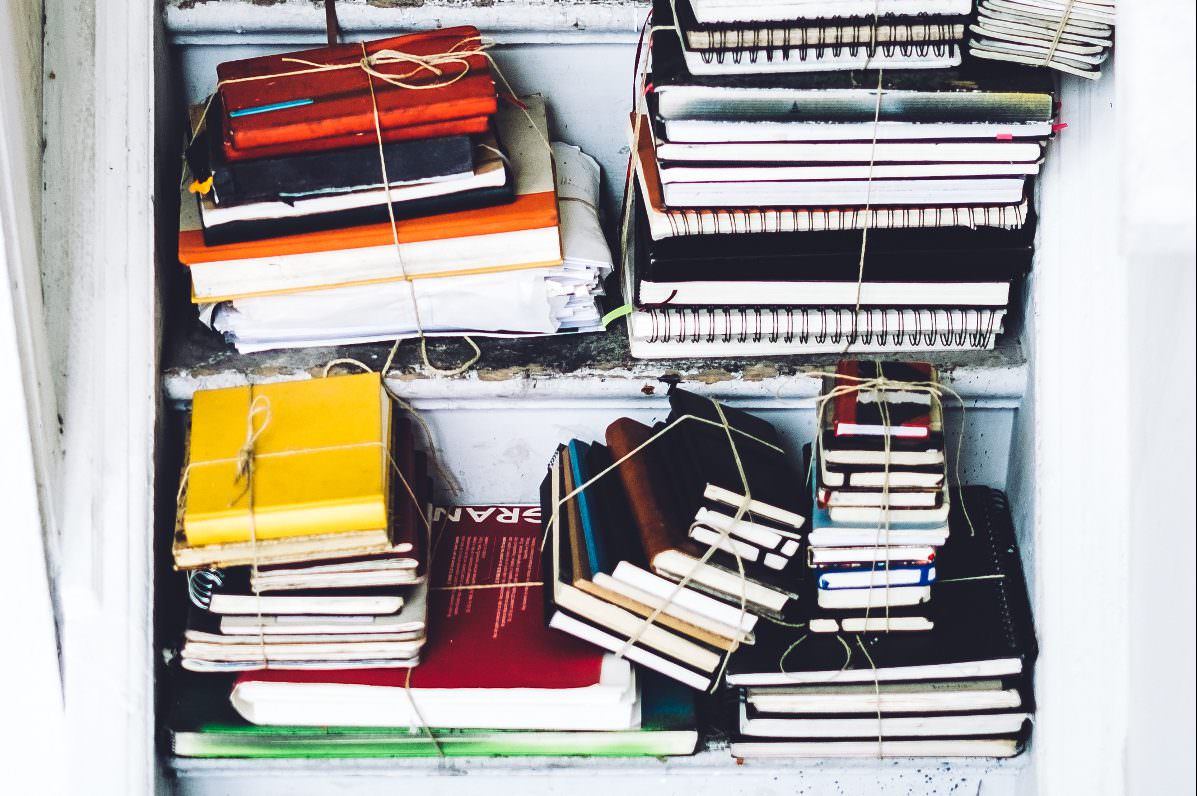

A Raft of Books

“Let’s not have any political correctness here. If characters can’t think and talk like people—if writers can’t—then what’s the point of literature?”

In my workshop with Frank Conroy at the University of Iowa in 2002, he uttered a caveat on the first day that was astonishing to hear at a university. “Let’s not have any political correctness here. If characters can’t think and talk like people—if writers can’t—then what’s the point of literature?” A casual leftist and no friend of the right, Conroy disdained manipulative politics of any brand.

His workshop was a godsend. I had just graduated from an Oregon Master’s program in which most professors taught absurd essays and opened the books rarely. For two years we explored Melville’s “homosocial environments” and Hemingway’s “repressive maleness,” etcetera. At the end of it, we were indeed masters—of an academic lunacy that doesn’t matter and won’t last. It’s a rare English department that respects great books and authors.

No wonder Conroy had moved the Workshop out of the English department a few years earlier, declaring its independence. He enjoyed discussing literature and how to write it, without any of the identity politics that attends the standard English course. My notebook soon filled with craft points, each one a valuable tool. “Abject naturalism: occurs when the writer describes too much for its own sake, forgetting [the constant demands of] brevity and purpose.” At the age of 33, I was finally learning something at college.

Author of Stop-Time and accomplished jazz pianist—Mingus called him “an authentic primitive”—Conroy was a lifelong rebel who achieved and demanded seriousness in the arts.

After those good years in Iowa City, many of us left town for university jobs. I taught around the Northwest for six years, in Boise and Portland, and received a part-time offer from a Christian university in Eugene. During the interview, the chair told me that faculty were encouraged to “be themselves,” but wanted me to know that the men tended to exude “a patriotic and chivalrous attitude.” Christian PC I did not need. I declined the invitation.

Weeks later I took a full-time job at Oregon State University—a comp-and-lit gig with a high salary and benefits. Author Bernard Malamud taught composition at OSU 1949 to ‘61. A leftist Jew at a land grant university, he was out of place among anti-communists in the department, who wore buzz cuts and had little interest in the humanities. The chair and some of the faculty referred to him as “the red.” He wrote a novel grappling with those years, called A New Life. Protagonist Sy Lavine navigates a spiteful, right-wing English department. Out of doors, enthusiastic administrators lead student rallies against the Russian enemy.

After a month on the currently left-wing campus, I was astonished to find how closely my own experience matched Lavine’s. From my office I heard the outdoor rallies organized by the Office of Diversity and Inclusion, the shouts and hoarse cries in a call-and-response method. Students and faculty cried out against whiteness on a campus that might have been the whitest place on earth.

The administration sent regular emails encouraging students and faculty to protest injustice on campus. Women’s Studies dispatched troops of undergraduates to storm the classrooms of male instructors reported as “sexist.” In a department meeting, the English chair mentioned that Women’s Studies required these protests in some courses. Herself a WS major at one time, she had “mixed feelings” about the intrusions, but encouraged us to “be careful” in our teaching.

Most of the men in the department stayed in their offices while in the building. A few of them posted regular feminist articles on Facebook, as if to obviate a visit from young women preparing for their futures by studying the art of misandry.

One English professor stepped softly, softly around campus. He had the gentle voice and constant smile of the fearful. Once, he told me about his non-fiction draft exploring how his milkshakes brought neighbors together.

He wasn’t a ridiculous man, but he might have been mistaken for a kind man. He wasn’t, he was merely nice, as though he’d found the last persona allowed to him in this environment. He was like a bright, 1950s housewife whose unappreciated talent had left her in increments, until her last asset was a smile that wasn’t her own.

But I often enjoyed teaching at Oregon State. The campus was old and gorgeous, a classic university setting with grand brick structures and wide lawns, most of it closed to vehicle traffic, a walker’s paradise. Before each term began, I liked visiting my classrooms and strolling the halls alone. One building smelled like a pool locker room, another like mildewed wood. But I seemed to feel ancient hatreds in the hallways, seeking hearts in which to perch like shaking fists of fire. The university had a long history of political blood-lust and reprisals.

When Barnard Malamud arrived on campus, he was chilled to hear that Ralph Spitzer—an associate chemistry professor with ambitions to educate the country about the global threat of the atomic bomb—was recently terminated for communist sympathies. President August Strand left the termination unexplained, and refused to answer several newspapers’ charges that it was a clear violation of academic freedom. Strand later argued in a speech to the Faculty Committee that Spitzer had embraced “Soviet science”—as if to justify the firing he refused to explain.

Some quarters of OSU continue to operate like bunkers of political extremism—especially the office of President Edward Ray, who has presided over several violations of academic freedom without a word. Ray was stamped out of the very machine that created August Strand.

When Art Robinson ran as a Republican for Congress in 2010, Nuclear Engineering attempted to deny graduation to his three children, all top performing students. One day I saw Robinson walking on campus, a grumpy-looking man in a work jacket and jeans. A few supporters followed behind him, holding signs that were pro-God, anti-gay. He and his cohorts wore the same hostile, life-drained expressions in fashion among left-wing radicals on campus—when the latter weren’t producing smiles for website photos, that is.

Right-wing Christian Art Robinson offered no improvement to the misery the regressive Left had engendered here. Still, his kids deserved the degrees they’d worked for, and they were finally allowed to graduate.

In another public case, climate-change skeptic Professor Nicholas Drapela was fired in 2012. The university declined to provide an explanation. In 2004 he won the Loyd F. Carter award for excellence in teaching.

Most political targets, though, didn’t make the news. One heard of professors let go for unpopular speech. Most of these “layoffs” occurred in the shadows, hushed up and the motivations placed in university vaults. And who could say they ever happened, when some layoffs really were the result of “departmental restructuring” and the like?

The Women’s Studies brigade finally invaded my classroom. It wasn’t much of an insurgency—three young women who seemed to lose their confidence upon entry. I recognized one of them as a former student, a big woman in a mullet. “What’s up with the black sex worker you mentioned last term?” she said. One of her companions inspected her phone. When the third woman left, the others followed.

One night writing at a local bar, a sex worker had asked me if I was the man she was supposed to meet. I said no but invited her for a drink. Though she was obviously high and therefore bad company, I enjoyed the looks of disapproval. The woman left before her drink was done.

My intention in speaking of the sex worker was to invite students to seek experiences beyond this campus gripped by enforced sameness. Maybe the story was a poor choice for a sophomore-level writing course. I confess to a mirthful immaturity, an impulse to disrupt. Author John Gardner asserted that writers are “churlish”—a rebelliousness now out of fashion, as more and more writers honor English department strictures forbidding unauthorized speech. This churlishness persists in my online and private instruction, along with a gravity of stewardship that I have felt for nearly all of my classes.

When I was laid off end of term, I returned to my home state of Idaho in 2013 with good news—a novel coming out, newly married, a baby on the way, and a part-time job teaching advanced fiction workshops to undergraduates at Boise State University. But at conservative BSU, PC was a frat-and-sports influenced Mormon climate. It felt like I’d landed at another Oregon State University, only the political poles reversed.

One of my students, a young man with hair in his eyes, waited until the end of class to speak to me one day. Maybe sensing a kindred dissenter, he told me about recent acts of censorship at the university. In 2008, university officials ordered 15,000 condom coupons destined for freshman eyes to be removed from circulars, by scissors. In 2005, they censored fliers that promoted university films and lectures by covering them with stickers to be “less offensive.”

It was as though church moms were everywhere, tidying up, dumping unclean books and magazines, and wiping all the windows that looked onto God’s blue sky.

Many students and faculty displayed a chipper, sporty friendliness, circa 1967. The assistant chair in the English department, a “Disney fanatic” who liked “zombie books,” was a student sports rep with a rocket-fuelled high-five. There were, however, serious men and women in the English department and the subsidiary MFA program.

By my second year, I wasn’t showing a lot of teeth on campus, amounting to a kind of sin in Boise where a popular bumper sticker reads, “You’re in Boise. Be nice.” I left a few high-fives hanging—even some powerful ones in the department.

After graduating from Iowa, I’d taught creative writing in an Idaho prison, and Writers in the Schools, Extended Studies, and Osher programs in Portland—wonderful all. I wanted to get back to that. I especially missed teaching older students, twenty seven plus, who tended to see by their own lights more than younger Millennials, famous for obeying their parents.

At this time I received a small inheritance. My wife and I tacked a US map onto our wall and circled the places we might go with our son. Becca wanted to see the East Coast. I’d already lived in New York City and Boston, so we decided to leave for Pittsburgh at the end of the term.

My first year at BSU had gone well. During the third semester, though, I couldn’t find my way into the giddiness of an intense workshop. A few of the students liked my instruction, but the scowling disapproval of half the class soured the dynamic. When we explored Alice Munro’s story “Wild Swans,” concerning a woman who endures a lengthy furtive groping by a stranger sitting next to her on a train—she enjoys the experience and is repulsed by it—many students in this senior-level class seemed incredulous that I even taught such a story.

I also mentioned during this class—again, perhaps unwisely—that I’d gone to the emergency room for lithium over one weekend, after my doctor moved without notice and my clinic refused to honor a medication refill. Though trying for humor, I doubt it came across. A few students exchanged glances. Assurances that I’d had not a single manic phase since I began taking medication in 2010 helped little. In Idaho, manic-depressives are referred to as “bipolar-schizophrenics” in the newspapers.

My workshops of student stories grew harsher, but always craft based, and never personal. One young woman brought in a therapy dog. I wished I had one.

A month into the term, I read the personal essay “My Dad, the Pornographer” in the New York Times, written by another fine Iowa teacher of mine, Chris Offutt. I loved the story about the man who endures the painful task of cataloguing his weird dad’s pornographic novels upon his death. I placed the essay on Blackboard, notifying students that we’d work it into our schedule. Offutt’s memoir, My Father, the Pornographer, was forthcoming. Later, in Pittsburgh, I wrote a review of the book for NYC’s The Rumpus.

It took some time for me to admit to myself a partial motivation in dropping this essay on students mid-term: to shake up small-minded religious kids and their parents—at a public university. A bigger part of me, however, wanted to wake my students who snooted through books and stories only to seek the unclean, inappropriate, unchristian. I wanted to vanquish their prejudices and reveal the exquisite honesty and psychological insights in “My Dad, the Pornographer”—or at the very least to whisper a smiling fuck you to all of those, young and old, right and left, who hate writers and literature.

A week before we’d planned to read the essay, a few students during class wanted to talk to me about my workshop—about my harsh teaching, and that essay on Blackboard. A young man shouted from the back of the room, “Why do I have to be here?” A young woman fled the room crying. Another admitted, when I asked, that at least one student, and possibly a parent, had complained to the department about the essay. A displeased middle-aged woman had started to wait for a female student at the classroom door.

At the beginning of the term, a dean had helped me eject a student who enjoyed shouting. This other shouter had taken up where he left off. When my class fell apart this time, a second dean swerved in to clean up the mess. He planned for the “Care Team” to observe my class—chosen faculty members and HR staff. A member of the Care Team was the director of the MFA program, my supervisor. He advised that I avoid teaching “My Dad, the Pornographer.” A fine writer and teacher, he had to go along, as he still answered to English. The following year, the rigorous BSU creative writing program pulled out of the English department altogether.

When the dean wrote me a third time about the Care Team’s visit, I wrote a rude email, using some profanity and referring to the students as “drama brats,” and was fired.

I regret my undisciplined remarks to the dean. It was impolite and stupid to write such an email. In addition, he had no tenable excuse to fire me for attempting to teach “My Dad, the Pornographer” until I wrote those words.

A sensational article about my firing and “lifetime ban” [language retracted] was published in the student paper the Arbiter:

While the university is legally prevented from releasing any details pertaining to the hiring or dismissal of personnel, the English Department denies that Blacketter’s removal was a matter of free speech or censorship. “This was not about academic freedom,” said Michelle Payne, chair of the English Department. “The reasons for it have to be serious. We don’t make the decision (to remove faculty) lightly.”

Given the legal restrictions, the dean’s choice to post my termination letter online after my firing is mysterious. “Your recent actions,” writes Dean Tony Roark, “are not consistent with the established Shared Values of the university.” It remains the one honest line in his letter.

Some of our best, even immortal, writers live and teach in these environments, for a while anyway. They can’t like it, though. I know they can’t, not the great ones.

It’s reassuring that a few serious English departments and creative writing programs still exist, like University of Chicago’s Department of English, the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and the Masters of Fine Arts at BSU. A special urgency attends their remaining so.

Most days, I avoid politics and dive into what Frank Conroy called “The river of literature.” When he spoke those words in workshop, I saw a raft made of great books, built for each writer alone. In the American writing life, it might finally serve as the last piece of stable ground we have.