US Election

Donald Trump and the Failure of Mainstream Social Science Part II

Large portion of social scientists seem to hold their surprise and perplexity as a badge of honour, rather than as an opportunity to improve their models of human behaviour.

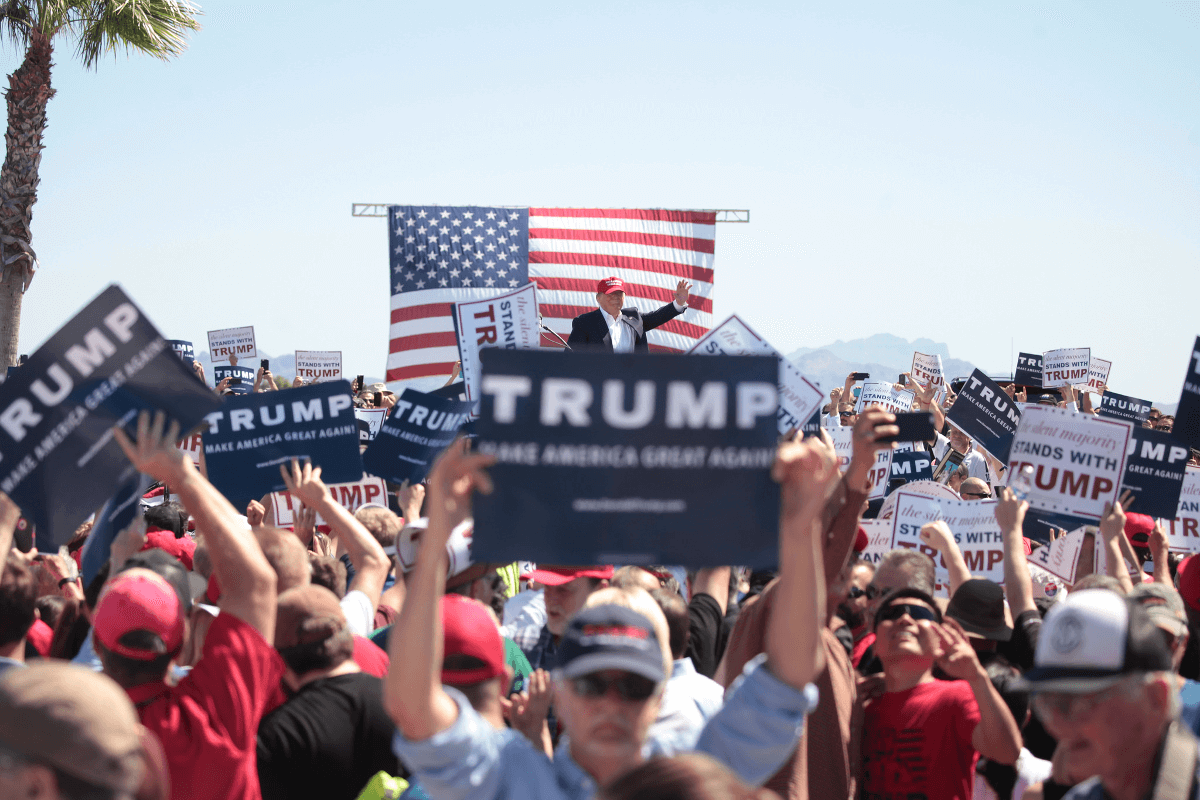

Donald Trump’s victory in the recent US presidential election was a shock to many people. Polls, media pundits, even political insiders almost universally predicted that Hillary Clinton would win comfortably. In the aftermath, there will surely be questions about why they misjudged the situation so badly. I would argue, though, that the problem runs much deeper.

The occurrence of a very similar situation in the United Kingdom a few months earlier suggests that this is not just a polling flaw, nor is it just a group of pundits misreading a single event. The underlying problem, I propose, is in the social sciences. These are the institutions expected to study human behaviour scientifically, and whose theories are spread to the rest of society.

Yet many social scientists have quite openly voiced surprise and perplexity at both the Trump and Brexit events, often supporting their statements with proclamations of immorality directed at the voters. There’s something disturbingly unscientific about this, in my opinion. Imagine a group of physicists responding to an event they are unable to explain by morally condemning electrons? This would never happen, of course, because it is accepted in the physical sciences that models are tentative, and that they must be adjusted when they make incorrect predictions.

Yet a large portion of social scientists seem to hold their surprise and perplexity as a badge of honour, rather than as an opportunity to improve their models of human behaviour. When scientists blame the world for not conforming to their models, rather than the other way around, something is wrong. But why do people who consider themselves scientists not adhere to basic scientific methodology?

The reason, I suggest, is that the social sciences have fostered an environment where certain beliefs are held above scientific inquiry, thus making them unchallengeable. Consequently, scientists are unable to adjust their models of human behaviour when they make poor predictions, forcing the scientists instead into a position of surprise, perplexity, and moral condemnation.

Consider the values Trump has been promoting throughout his campaign. When he promises to make America great again and complains that America doesn’t win anymore, when he promises to reduce government, when he aggressively goes after his opponents, and when he refuses to couch his words in equivocation, he is not just offering a new political direction, he is thumbing his nose at contemporary moral beliefs, and many people are responding to it, especially men.

People have been taught for years that traits such as competitiveness, individualism, aggression, confidence, and national pride are morally suspect, and here comes a figure who is unafraid to challenge that. I’ve heard mentioned that Trump is tapping into many people’s disdain for political correctness, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg, in my opinion. I think he’s tapping into a broad resistance to contemporary moral beliefs, beliefs that have become increasingly institutionalised over the past fifty years.

The problem is that these are precisely the beliefs that are held above inquiry in the social sciences. Under normal scientific conditions, scientists would simply say ‘oh, it looks like we underestimated the extent to which these values are drivers of human behaviour, let us adjust our models’. But social scientists can’t do that, so all they can do is declare them immoral, whether it be Brexit, or Trump, or the movements in France and Germany and many other Western countries that are currently building.

It isn’t just that social scientists disagree on the details of how important this behaviour is to people, but that even discussing it in anything other than strongly moralistic terms is discouraged. And so, social scientists face a dilemma. Treating individualism, competitiveness, confidence, aggression, and national pride as behaviour worthy of description dilutes the power of ideologies to moralise against them. And this threatens the left, which dominates the social sciences and whose ideology is based on declaring these behaviours immoral. It’s hard for social scientists in this environment to remain objective, and since there are virtually no social scientists with opposing views, the science suffers.

Fortunately, this is about to change. A new group of people with heterodox views are emerging in universities throughout the West, sparked mostly as a counter-reaction to the social justice warrior movement that has intensified its pressure on universities. These people don’t just get their information through the mainstream media, and some of them may define themselves unapologetically as being in opposition to some or all contemporary moral beliefs. As they enter the social sciences they will challenge these beliefs, and the best way to challenge them is to examine them scientifically, without holding them in reverence. If they can build better models of human behaviour by doing so, these models will replace existing ones.

History shows that in the long run, the better science wins. If one scientific community is unable or unwilling to submit its beliefs to scientific treatment, it will be outcompeted by another that will.

See also: Donald Trump and the Failure of Mainstream Social Science Part II

Donald Trump and the Failure of Mainstream Social Science Part III