Why Are Rates of Mental Illness Soaring Among Young Women?

The world is theirs for the taking — only a significant proportion are, it seems, too anxious, depressed and traumatised to take advantage.

Young women today do better at school than boys, they are more likely to go on to university, take more of the top jobs and, at least until they are thirty, earn more than men. Yet women are clearly not celebrating. In Britain, research published last week shone a light on the state of the nation’s mental health. It revealed an alarming increase in the number of women aged 16 – 24 reported to be suffering from a mental health condition. This echoes the findings of similar research conducted in Australia and America.

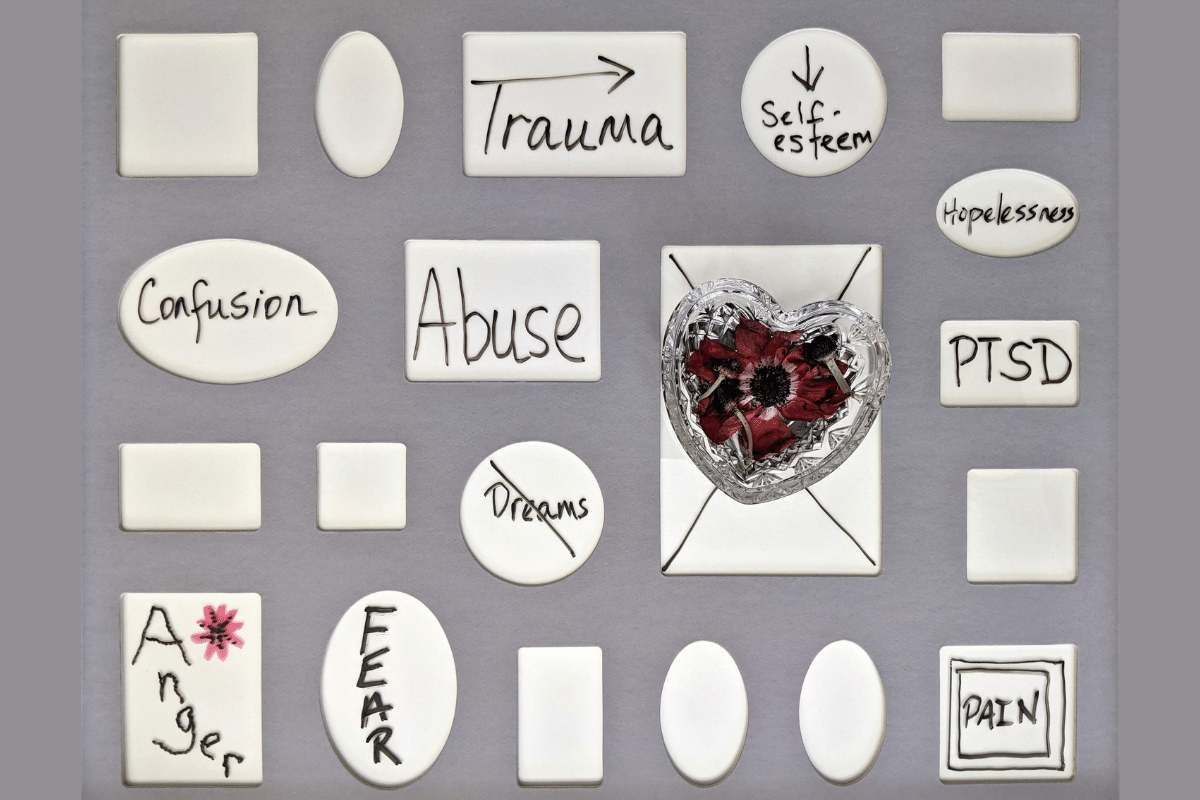

According to the latest statistics, almost 30% of young British women have a problem with their mental health. One in five suffer from anxiety, depression, panic disorder, phobia or obsessive compulsive disorder; this compares to 12 per cent of men the same age. The number of young women screening positive for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder has trebled to 12.6 per cent in just seven years. Almost 20 per cent of women aged 16 – 24 report self-harming. For once, headlines that shout about a ‘crisis’ or an ‘epidemic’ appear justified.

Yet unlike their great-grandmothers, who may well have experienced the trauma of war and the hardship of rationing, before being corralled into stupefying domesticity, today’s young women have it good. They may not have a career, mortgage and baby all before the age of 25 but they perhaps have something even better: their freedom. Few young women today are constrained by either biology or social convention. The world is theirs for the taking — only a significant proportion are, it seems, too anxious, depressed and traumatised to take advantage.

Popular explanations for this sad state of affairs tend to focus upon the pressures young women experience to live through the prism of social media; the ubiquity of pornography and the need to look good at all times. But this risks slipping into tautology. It leaves unanswered why women respond to these pressures and don’t choose to ditch the eating regimes and mute their phones. We need to dig deeper.

Recent years have witnessed a growth in campaigns and awareness raising initiatives around the issue of mental health that are often aimed specifically at young people. From their earliest years in school many children, especially girls, adopt a vocabulary of ‘stress’, ‘depression’ and ‘anxiety’. Lessons in mindfulness and meditation urge children to focus inwards and consider their personal emotional state rather than running around outside or exploring topics that will take them beyond their own internal monologue.

At university, poster campaigns advertise support services and urge students to look after themselves and each other. Soap operas, advertising campaigns and the Tweeted struggles of YouTube stars reinforce the message that young people are mentally vulnerable. As a result, young women are increasingly open about discussing their mental health. As one journalist reports: ‘My female friends and I have discussed, without shame, everything from depression to panic attacks to suicide attempts to miscarriages to cocaine-induced paranoia (drugs and alcohol use are so obviously a factor in mental illness) to eating disorders and OCD.’

Obviously, if someone is suffering from a mental health problem then they need to have the best help and support put in place as quickly as possible. But there comes a point where all the awareness raising creates more problems than it solves. We risk losing the ability to discriminate between the emotional ups and downs that are part of growing up on the one hand and serious conditions on the other. We tell children that feeling stressed or anxious from time to time is not normal but something they need special help to deal with.

We have successfully thrown away the stigma surrounding mental health but in the process we have normalised what were once serious and rare problems. For young women today there is no shame attached to discussing feelings of anxiety or depression. The opposite is the case and just as women rarely admit to feeling completely happy about the way they look, so too will few admit to being totally mentally robust and resilient. Young women who openly display their suffering are lauded for bravery and honesty. Stigma has been replaced with kudos.

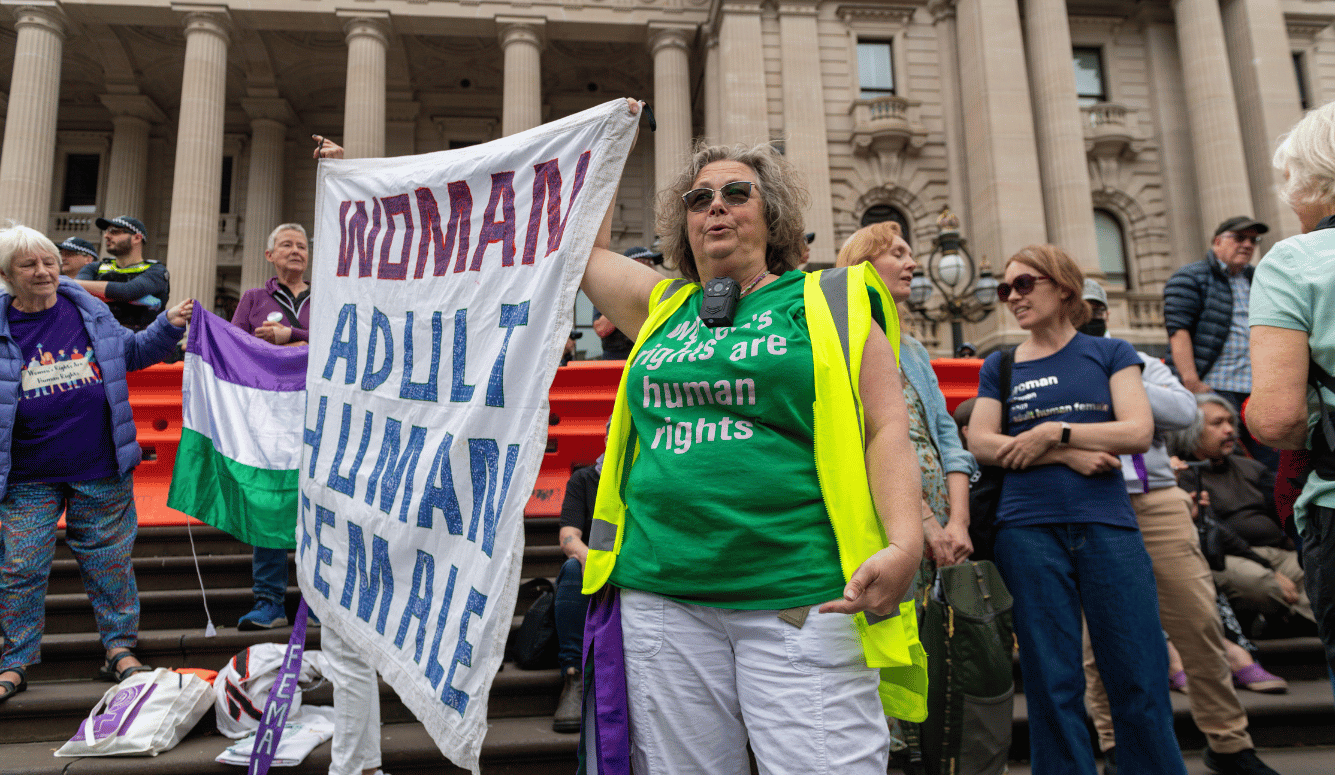

In an age of check-your-privilege identity politics, mental health problems come to define people. They mark some individuals out as more fragile and special than everyone else. This vulnerability can be publicly displayed through self-inflicted scars; the practice of self-harming makes a young woman’s suffering visible to the world. Writing in The Second Sex, Simone De Beauvoir recognised the trend for girls to self harm, remarking that such actions were, ‘more spectacular than effective … she remains anchored in the childish universe whence she cannot or will not really escape; she is struggling in her cage rather than trying to get out of it.’

The cult of awareness raising offers one explanation as to why so many young women have come to see themselves as mentally ill. But there is more to it than this. Today’s children, labelled ‘cotton wool kids’ and ‘generation snowflake’, have been kept securely in their cages. Cosseted girls who never venture outside their own homes unaccompanied are likely, once they gain such freedom, to find the world a genuinely more scary place. For women these fears are no doubt exacerbated by feminist ‘rape culture’ scare stories.

An honest discussion about young women’s mental health problems is impossible while we blindly respect, rather than question, claims to suffering. It can seem as if the only response permitted is to demand more money for mental health services, more awareness raising and quicker access to treatment therapies. But this is an inadequate solution and will only exacerbate the scale of the current crisis even further.

Doctors are not immune to the awareness campaigns – indeed, most surgery walls are lined with posters. Rather than a shocking increase in mental health problems, perhaps we are instead witnessing a growing tendency for people to seek help when they experience feelings they have been taught to view as problematic and, at the same time, an increasing number of doctors ready to diagnose, medicalise and prescribe treatments for such normal human emotions. In this case, the only real surprise it that so few young women suffer.