'Socialism': Why the Word Matters

Sanders has also popularized the notion of socialism within the American zeitgeist. ‘Socialism’ used to be a bad word, but it isn’t anymore.

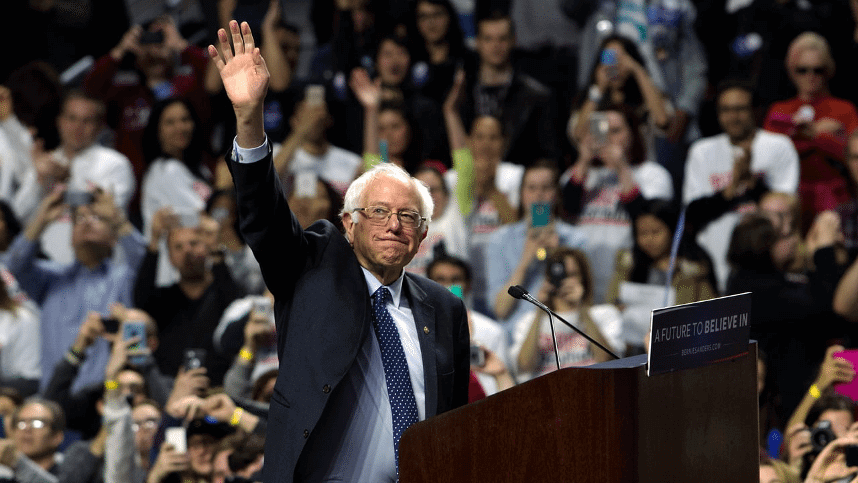

Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign is practically over, but its impact is bound to be lasting. The Vermont Senator has achieved a remarkable feat in energizing voters, especially millennials, getting them more involved in the political process.

He has also moved the public discourse in America leftward, by connecting with voters on economic issues that matter to them. College graduates in America are experiencing record levels of student debt, wages for the middle class have stagnated, and many Americans have trouble accessing quality healthcare. Sanders hopes to mitigate these problems by making public college tuition free, raising minimum wages, boosting government spending (particularly in infrastructure), and aiming to bring about a single-payer healthcare system.

During the course of his wildly successful campaign, Sanders has also popularized the notion of socialism within the American zeitgeist. ‘Socialism’ used to be a bad word, but it isn’t anymore. A recent YouGov poll found that more than a third of the population between the ages of 18-29 has a favorable view of socialism.

What does ‘socialism’ mean? According to Sanders, a self-described “democratic socialist,” his governing philosophy basically involves the incorporation of a robust social safety net, free college education, and universal healthcare, among other things, and a more progressive taxation scheme to fund these things.

However, this is importantly different from what ‘socialism’ has traditionally meant. Socialism, in this sense, involves the public (or state) ownership of the means of production, such as factories and farms. Typically, this is to be accompanied by state control of the means of distribution, such as retail markets and transportation systems.

These two notions of socialism are extremely important to keep distinct. The latter form of government has been an unmitigated disaster every time it has been tried, and is responsible for an unfathomable amount of human suffering since it was first attempted via the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 in Russia.

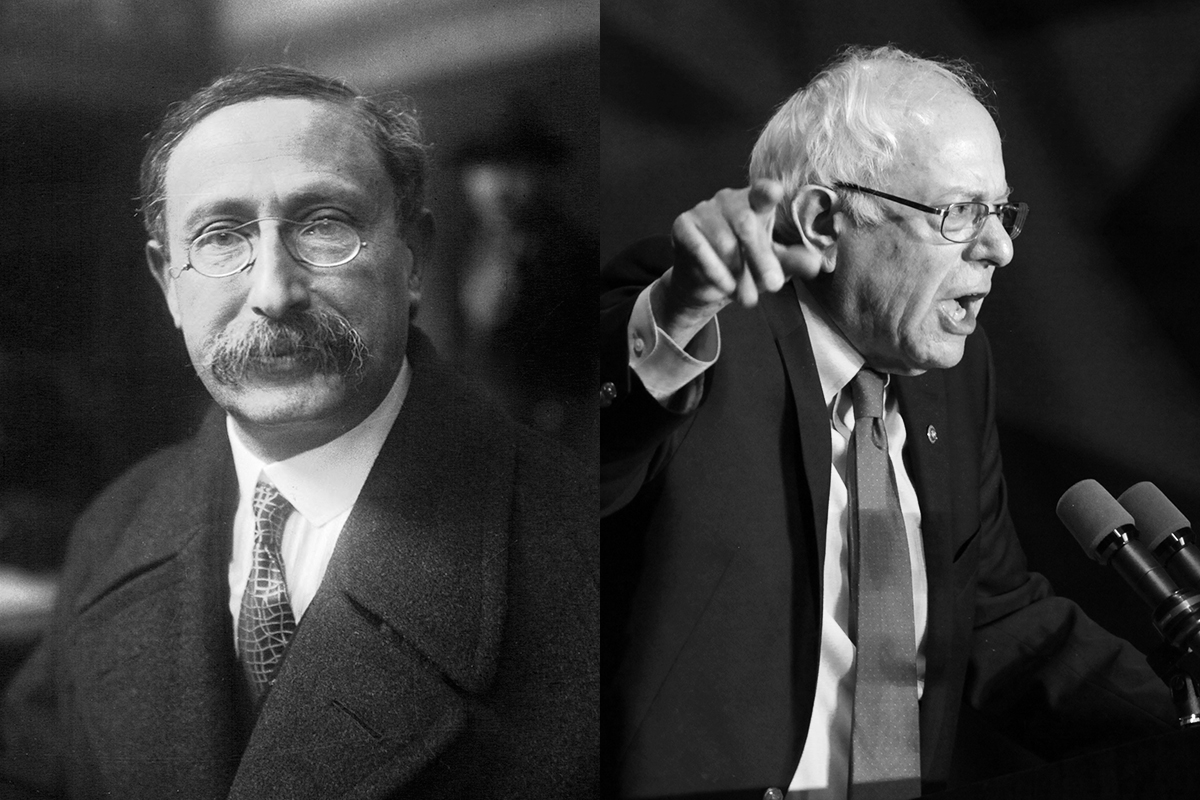

The question of what mechanisms explain the failures of centrally planned economies is up for debate. One popular explanation, first put forward by Ludwig von Mises, is that the lack of market pricing mechanisms within centrally planned economies causes inefficiencies that lead to shortages of essential goods within the system.

Whatever the ultimate explanation, the historical facts are undeniable. Centrally planned economies, within which the state operates the means of production and distribution, have uniformly led to chronic shortages of essential goods, often producing massive famines. Life for ordinary citizens within China, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Myanmar was a nightmare when the state monopolized the means of production. Forty-five million people are estimated to have died of starvation in Maoist China alone, as a result of state monopolization of the agriculture sector.

Devoted socialists often argue that dictatorial regimes, rather than central planning, caused these disasters. This is wishful thinking for two reasons. First, even in contexts where state nationalization of most of the industry has operated within a democratic system, standards of living have been extremely low. For example, until the 1990s, India’s economy operated under a “license raj,” where most large industries — banking, mining, airlines, etc. — were publicly owned, and only a few private players, along with mom and pop shops, were allowed to compete. And until the nineties, India had some of the worst rates of poverty in the world. Following the partial liberalization of the economy by the Prime Minister Narasimha Rao, the country has seen remarkably higher growth rates, and millions have been lifted out of poverty.

Second, even socialist regimes that are democratically elected often turn into dictatorships, because that’s the only way to remain in power following the shortages that their policies bring about. Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe is an excellent example. Following his nationalization of industry and implementation of land redistribution policies, Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia) went from being one of the most prosperous nations in Africa to being one of its poorest. Had Mugabe allowed free and fair elections since his rise to power, he surely would have been voted out by now.

The most recent socialist debacle is Venezuela, where democratically elected Hugo Chàvez eventually became a de facto dictator. The country is now collapsing, facing shortages of everything from toilet paper to basic groceries and medicines. And this is so despite Venezuela having been a relatively prosperous country within Latin America in the not too distant past, and having vast oil reserves.

Given the economic history of the last hundred years or so, it is thus important that we do not repeat the mistakes of the past. Now, Bernie Sanders is no Hugo Chàvez – he shows no interest in nationalizing industries or setting prices. Sanders’ ideal model is that of Scandinavia, where the private sector and international trade are allowed to flourish, but nonetheless, the government plays a key role in ensuring that all citizens have access to education, healthcare, and robust unemployment benefits.

The danger, in Sanders’ labeling policies his policies as ‘socialist‘ — whether democratic or not — is that the boundaries between the two systems may begin to blur. And millennials, if they don’t keep the distinction firmly in mind, may find themselves supporting politicians who do want to nationalize industries.

Perhaps realizing the potential of this slippery slope, socialist politicians have been keen to align themselves with the Sanders campaign. Consider the Socialist Alternative (SA), an organization that campaigned to elect Kshama Sawant into the Seattle City Council. Among the policies that the SA eventually wants to see adopted in the U.S. is the nationalization of the entire Fortune 500. Anticipating that the immense popularity of the Sanders campaign offers a unique opportunity to expand the socialist base, SA has been actively considering strategies to mold Bernie’s “revolution” into a genuine socialist movement.

Senator Sanders himself is partly to blame for this. He should stop calling himself a socialist — he simply isn’t one. Many have suggested “social democrat” as a more appropriate label.

On the flip side, conservative commentators have exacerbated the problem by crying wolf every time they see some effort towards social democratic reform. President Obama’s Affordable Care Act has repeatedly been dubbed “socialist,” for example. These commentators also jump to criticize Sanders as being socialist. Doing so has no doubt promoted their short-term political goals. Insofar as there is still resistance to the notion of socialism, conservative politicians and pundits have leveraged this uneasiness in an effort to reduce the popularity of the Sanders campaign.

But doing so runs the risk of Americans — especially millennials — becoming less wary if and when a real socialist comes along. And given the repeated lessons of history, this is not something America, or the world, can afford.