Religion

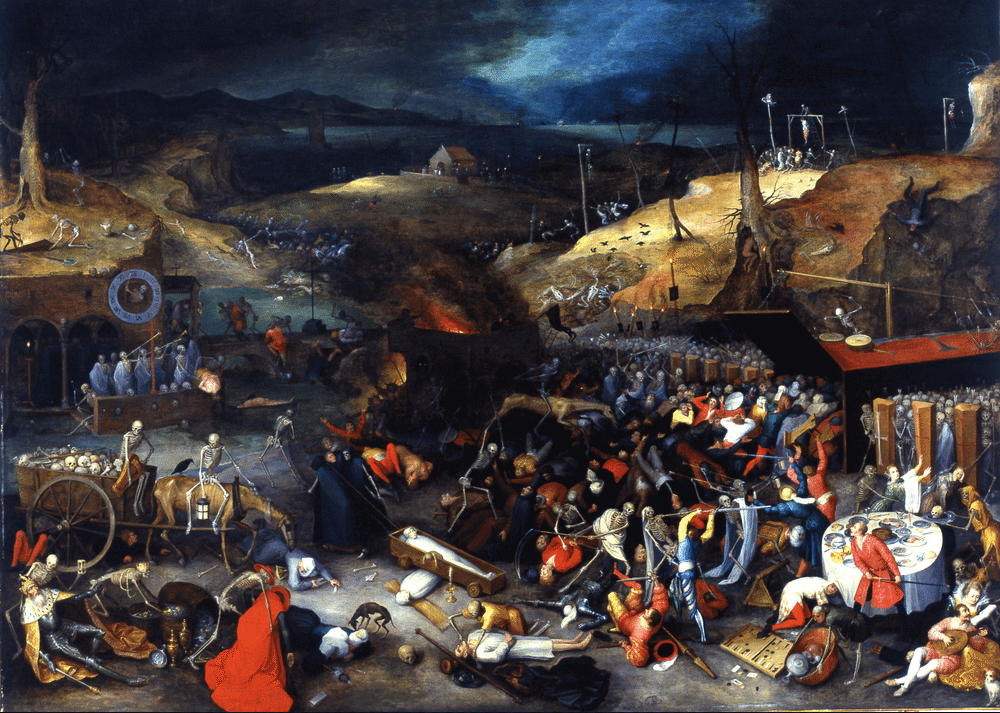

In Their Rush To Blame Religion, New Atheists Overlook Evil

Pragmatists differ from rationalists by viewing unfiltered criticism of religion as a painfully counterproductive way to proceed.

Two schools of thought exist on the question of how best to criticize religion if you’re a nontheist. The first belongs to rationalists who believe in the value of strongly criticizing religion, even if that means upsetting or offending religious believers. By being open and honest about the severity of the problems that religion faces, rationalists aim to jar believers free from its grip.

This doesn’t tend to make rationalists very popular with believers, of course, but rationalists see virtue in accepting the truth even when it is unpleasant or ugly. To paraphrase Bertrand Russell, it is better to throw open the shutters to the cold light of day, even if the fresh air makes us shiver at first, than to dwell in the warm but false confines of humanizing mythologies.

Pragmatists differ from rationalists by viewing unfiltered criticism of religion as a painfully counterproductive way to proceed. As they may note, people do not merely believe in religions — they are personally invested in their truth and anchor large parts of their identities around them. Given this, a softer, more measured approach is called for. After all, sharply criticizing the beliefs that people treasure, or worse, ridiculing those beliefs and offending believers over them, risks making it very difficult for people to accept what you say.

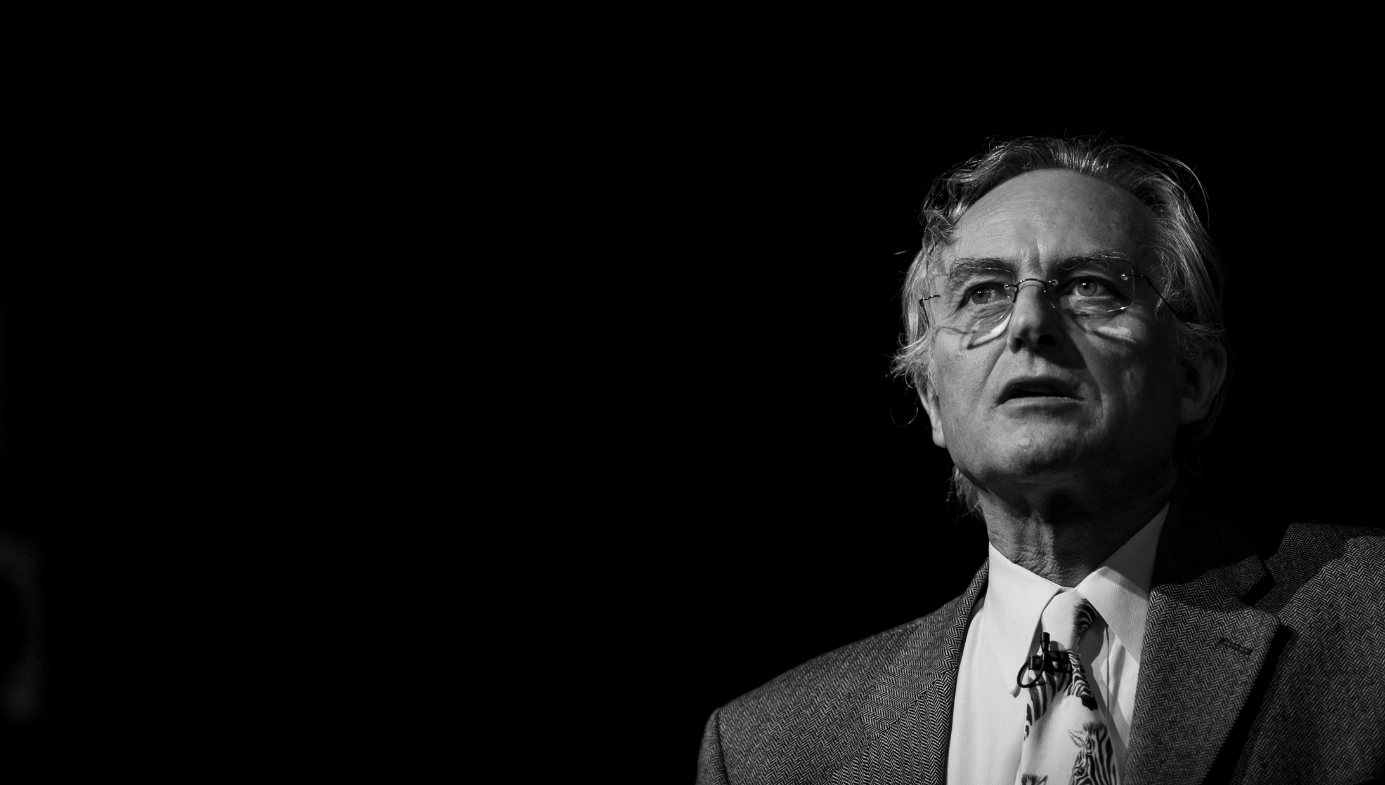

New atheists belong very much on the rationalist side of things under this taxonomy. When Christopher Hitchens subtitled his book God is Not Great with “how religion poisons everything,” and when Richard Dawkins kicked off his bestselling book The God Delusion with an entire paragraph of pejorative adjectives aimed at the God of Christianity, little if anything was being held back to spare the feelings of the religious.

While opinions diverge over the wisdom of their approach, unflinching criticism of religion has been beneficial to new atheists in at least one respect, and that is that it has been enormously helpful in getting them heard. This is no trifling thing, either, for those who go unnoticed don’t change anything.

Unfortunately, one of the first victims in the struggle to be seen and heard can be the truth, and some leading new atheists have gone well beyond what can be justifiably said about religion.

This is nowhere more evident than in a remark by Nobel Prize winning physicist Steven Weinberg that “with or without religion, good people can behave well and bad people can do evil; but for good people to do evil — that takes religion.” Short and to the point, Weinberg’s rebuke has been quoted with approval by several leading new atheist figures since, including Lawrence Krauss, Bill Maher, Richard Dawkins, and Christopher Hitchens. Indeed, as Dawkins himself hailed, Weinberg’s comment is “so devastatingly true that it is worth quoting again and again.”

Judging by search engine returns you get when you google it, many atheists appear to have done exactly that. The reasons why aren’t hard to find. Condemning religion two easily digestible sentences, Weinberg’s claim succinctly reduces a complicated moral puzzle to a black and white world where religion alone is responsible for the corruption of good people. It is the equivalent of porridge for the brain.

There is just one small, nagging problem: what Weinberg said is strikingly false. How do we know? Because history tells us it is.

The end of the Second World War saw millions of women in Europe end up the victims of rape by Russian soldiers. As pointed out by University of London historian Antony Beevor in Berlin: The Downfall 1945, the attacks were particularly bad in Berlin, the heart of Nazism in Europe, where girls as young as 8 and women as old as 80 were raped by drunken soldiers, sometimes by gangs of them, and sometimes to death.

It is far too much to believe that the perpetrators of these crimes were all intrinsically bad or “evil” people acting in accordance with their static moral characters. A far more plausible explanation is that a variety of causal factors culminated to produce this historical tragedy, including the lack of control that officers exerted, the large quantities of alcohol the soldiers consumed, and the desire felt by many on the Russian side to inflict revenge on the Germans for four years of grueling horror on the Eastern front. What you won’t find mentioned in the list of relevant causal factors, however, is religion.

If history isn’t your favorite subject, field-defining research in social psychology reveals exactly the same truth. We know from experiments by Stanley Milgram in the 1960s, for example, that pressure to obey authority led around two-thirds of test subjects who believed they were helping with a memory experiment to apply severe electric shocks to another person who kept failing word association questions. In fact, they applied the shocks so diligently that they continued even after the person in the other room had collapsed unconscious, and did so all the way to the maximum setting on the shock machine. Why would anyone ever do that, you ask? Because a lab technician standing next to them insisted that for the purposes of the experiment not answering was the same as answering incorrectly, and therefore required the shock. A mere technicality, in other words.

The point here is that what Weinberg said isn’t simply exaggerated, it’s wrong. Religion, though entirely capable of bringing otherwise good people to do morally evil things, is not in any sense required for that. Sometimes all it takes is a guy in a grey lab coat.

Unfortunately, saying otherwise does more to damage the cause of new atheism than it does to help it, and you don’t need to be a pragmatist to see that. The fact is that mistaking the moral responsibility of religion in producing evil through your own bias or oversight makes it that much harder for others to trust what you say. After all, if the most vociferous new atheists can get this particular issue badly wrong, what else may they? Questions of this kind are easy to ask in light of such examples.

The issue here is not a minor one and should not be overlooked. In fact, it represents nothing less than a test of the soul of new atheism, for if Dawkins, Maher, Krauss and Weinberg won’t correct themselves, they betray the very same principles of rationalism they ask others to live by.

To new atheists I therefore say: let Weinberg’s claim go, and say that you did. Not only would doing so set a fine example in how to deal with falsehood when it is your own, the intellectual integrity of new atheism depends upon it.