Free Speech

Free Speech and Islam — In Defense of Sam Harris

If you discount Islamic doctrine as the motivation for domestic violence and intolerance of sexual minorities in the Muslim world, you’re left with at least one implicitly bigoted assumption.

The controversial atheist needs a fair hearing

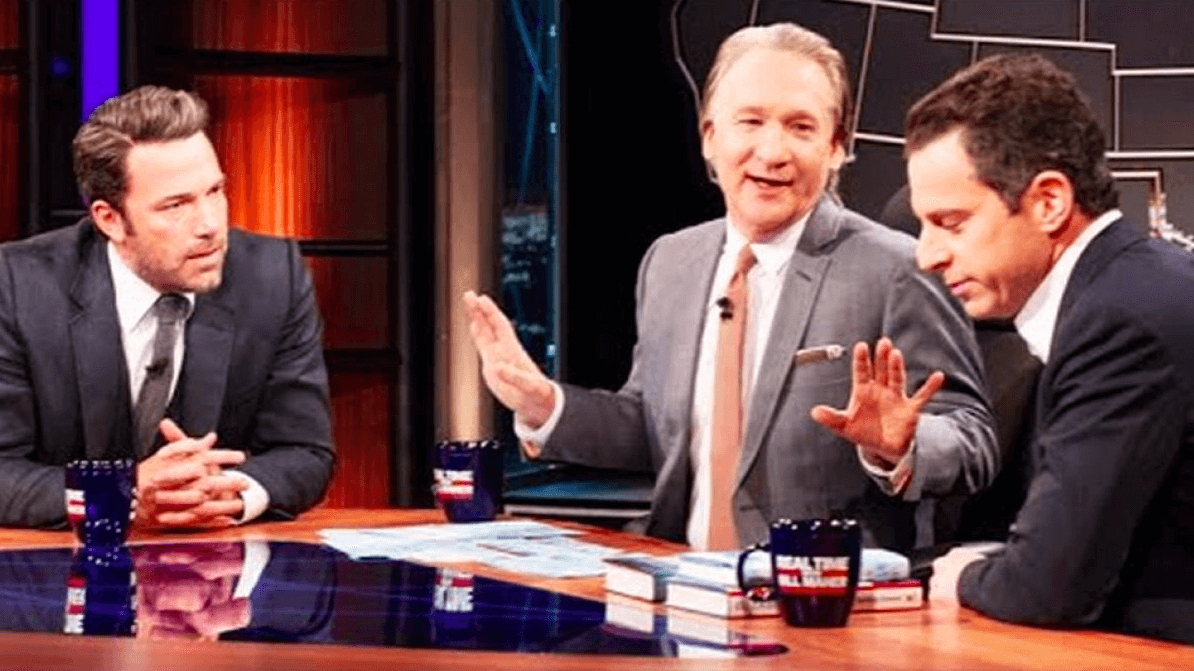

“It’s gross! It’s racist!” exclaimed Ben Affleck on Bill Maher’s Real Time in October 2014, interrupting the neuroscientist “New Atheist” Sam Harris. Harris had been carefully explaining the linguistic bait-and-switch inherent in the word “Islamophobia” as “intellectually ridiculous,” in that “every criticism of the doctrine of Islam gets conflated with bigotry toward Muslims as people.” The result: progressives duped by the word shy away from criticizing the ideology of Islam, the tenets of which (including second-class status for women and intolerance toward sexual minorities) would, in any other context, surely elicit their condemnation.

Unwittingly, Affleck had confirmed Harris’ point, conflating religion with race. In doing so, the actor was espousing a position that can lead to a de facto racist conclusion. If you discount Islamic doctrine as the motivation for domestic violence and intolerance of sexual minorities in the Muslim world, you’re left with at least one implicitly bigoted assumption: the people of the region must then be congenitally inclined to behave as they do.

There was a disturbing irony in Affleck’s outburst. Few public intellectuals have done as thorough a job as Harris at pointing out the fallacies and dangers of the supernatural dogmas of religion, for which far too many are willing to kill and die these days. An avowed liberal (who plans to vote for Hillary) Harris is the author of, among many books, the groundbreaking The End of Faith. Yet Affleck seemed predisposed to regard him with hostility, possibly because Harris, at least for some on the Left, has acquired a toxic reputation — one stemming from what amounts to a campaign of defamation involving, by all appearances, a willful misrepresentation of his work, plus no small measure of slipshod “identity politics” thinking.

Harris has been lambasted as, among other things, a “genocidal fascist maniac” advocating “scientific racism,” militarism, and the murder of innocents for their beliefs, as well as racial profiling at airports, a nuclear first strike on the Middle East, plus, of course, Islamophobia and a failure to understand the faiths he argues against. (This is just a partial list.) The result? Harris has had to take measures to ensure his personal security, with negative ramifications in almost every area of his life. “I can say that much of what I do,” he told me in a recent email exchange, “both personally and professionally, is now done under a shadow of defamatory lies.”

The attacks against Harris have emanated predominantly from a prominent yet persistent handful of supposed progressives (and their peons), among whom are the religion scholar and media personality Reza Aslan, and the journalists from The Intercept, Glenn Greenwald (famed for transmitting Edward Snowden’s NSA revelations to the world) and Murtaza Hussain. Lately, with Harris’ publication of Islam and the Future of Tolerance, they have even taken aim at his coauthor and friend, the onetime Islamist turned reformer Maajid Nawaz.

Nonetheless, Harris’ own words, conveyed through his books, podcasts, blog posts, interviews, and Twitter feed, bely the attacks, which can be as mean-spirited as they are groundless and muddled. They have tainted the debates we need to conduct about Islam and terrorism in particular, but, more generally, the danger religious fundamentalism poses to our constitutionally secular republic and to the largely post-Christian countries of Western Europe now confronting huge inflows of Muslim migrants. The sum effect is to leave us all less well-off, less safe. And certainly more confused.

The charge of insufficient religious expertise is the least substantial, but nonetheless worth dispensing with, given that it could potentially be leveled at any nonbeliever disagreeing with faith’s precepts. In a 2007 debate, for instance, Reza Aslan accused Harris of having a “profoundly unsophisticated” view of religion, and of relying on Fox News as his “research tools” – an assertion that can be disproved by just opening The End of Faith, a meticulously compiled treatise with 237 pages of text (in the paperback edition) followed by sixty-one pages of footnotes and twenty-eight pages of bibliography listing some six hundred sources. In this opus, Harris walks us through the many follies of faith (mostly Christianity and Islam), but one key message transpires: belief guides behavior. A self-evident proposition no reasonable person would argue with.

Which has not stopped Reza Aslan from doing just that. Writing in relation to Harris’ skirmish with Affleck, Aslan has stated that religion “is often far more a matter of identity than it is a matter of beliefs and practices” and that “people of faith insert their values into their Scriptures,” with other, often contingent factors causing them to act as they do. So when ISIS guerrillas behead their captives, justifying their bloodshed by proclaiming jihad and citing verses from the Quran, by Aslan’s definition we cannot blame the doctrine of jihad or the contents of Islamic scripture, but must seek out other motives. This is prima facie obfuscatory, because it involves discounting the testimony of the perpetrators themselves.

The “genocidal fascist maniac” moniker was born of a certain @dan_verg_ on Twitter (account since suspended), and retweeted by Reza Aslan and Glenn Greenwald. The tweet misquoted, without context, a line from Harris’s The End of Faith: “Some beliefs” — “propositions” in the original — “are so dangerous that it may be ethical to kill people for believing them.” Which suggests Harris might endorse the death penalty for thought crime.

Yet context is critical and deprives the words of controversy. As is clear in reading the text, Harris was discussing terrorism and how to deal with the likes of Osama bin Laden, a fanatically committed ideologue with the capacity and demonstrated willingness to order others to murder on the basis of his (religious) beliefs. (Harris was not, thus, proposing death for thought crime.) Following the last line cited above, Harris wrote: “Certain beliefs place their adherents beyond the reach of every peaceful means of persuasion, while inspiring them to commit acts of extraordinary violence against others . . . . If they cannot be captured, and they often cannot, otherwise tolerant people may be justified in killing them in self-defense.” (Italics mine.)

Note “If they cannot be captured.“ The beliefs in question? Not surprisingly, those of jihad and martyrdom, the primum mobile for the 9/11 hijackers (and so many other Islamist terrorists since then). As Harris went on to note, 9/11 proved “beyond any possibility of doubt that certain twenty-first-century Muslims actually believe the most dangerous and implausible tenets of their faith.” This is a truism, not evidence of an Orwellian mindset, and it underlies the U.S. government’s targeted assassinations of radical Muslim clerics and Al Qaeda and ISIS commanders, carried out before such people have a chance to harm Americans. Such killings are, to be sure, controversial, but the proposition that belief in certain tenets of Islamic doctrine can lead to murderous behavior is not.

The charges of “scientific racism” and “militarism” hurled at Harris in an Al Jazeera essay by Murtaza Hussain derive from a maliciously “creative” misrepresentation of his critique of Islam and illogical, erroneous extrapolation therefrom. Murtaza’s essay is chiefly an exercise in innuendo, and opens with a lengthy prelude about “scientific racism,” phrenology, and even drapetomania (a long-discredited theory ascribing mental illness to slaves desiring to flee their servitude), which sets up his premise: “a new class of individuals” — Harris foremost among them — “have stepped in to give a veneer of scientific respectability to today’s politically-useful bigotry” — the New Atheists, some of whom happen to be scientists.

The New Atheists, according to Hussain, “[w]hile . . . attempt[ing] to couch their language in the terms of pure critique of religious thought, in practice . . . exhibit many of the same tendencies toward generalisation and ethno-racial condescension as did their predecessors — particularly in their descriptions of Muslims.” Hussain tells us that “mainstream atheists must work to disavow those such as Harris who would tarnish their movement by associating it with a virulently racist, violent and exploitative worldview.”

This is all textbook begging the question: assuming as true the very propositions (that New Atheists are racist, militaristic, exploitative) that one has first to prove. Hussain follows this with a distortion of Harris’ videoed remarks concerning the distressingly high percentages of British Muslims who wish to live under Sharia law, and favor death for apostates and the arrest and prosecution of neighbors who insult Islam. Harris concludes that “these people do not have a clue about what constitutes a civil society,” which Hussain distorts as applying to “Muslims as a people.” No definition of “civil society” can expand sufficiently, of course, to encompass the niceties of Sharia, which include stoning, beheading, and chopping off hands.

From this distortion Hussain proceeds to warn us that “Harris’ pseudoscientific characterizations of Muslims dovetail nicely” with his “belief in the need to fight open-ended war against Muslims” (no source indicated, no sample quotes from Harris provided) which would involve launching a “wholesale nuclear genocide” against them.

Harris has never called for “open-ended war against Muslims.” The thrust of his work regarding Islam concerns the “war of ideas” we are waging against radical Islam, which has, though, since 9/11, been accompanied by military action. For “wholesale nuclear genocide” (of Muslims), Hussain provides no source, but it comes straight from journalist Chris Hedges — a proven plagiarist, no less. Hedges alleged, based on graphs in the middle of The End of Faith, that Harris has called for “a nuclear first strike on the Arab world.” But check Harris’s words and you will find only a lucid discussion of the possibility that an Islamist regime (guided by the doctrines of jihad, martyrdom, and the primacy of paradise) might acquire long-range nuclear weaponry — an eventuality that could, he writes, prompt its opponents to launch “a nuclear first strike” (which he calls “an unthinkable crime”) as the “only thing likely to ensure our survival” against said regime. Fears of just this motivated the P5+1 countries to conclude the recent nuclear accord with Iran. (For Harris’ response to Hedges and his claim, check out his trenchant squib “Dear Angry Lunatic.”)

Perhaps the most pernicious, undiscriminating, and widely circulated attempted takedown of Harris came from Glenn Greenwald, who published his prolix, scattershot assault on reason in The Guardian. Space prevents me from addressing all the article’s blunders and boners, so I will deal with those that have had some purchase among the most hypocritical of the Left.

Citing Hussain’s article and one penned by Nathan Lean (research director at Georgetown University’s project for Pluralism, Diversity and Islamophobia, and a former employee of Reza Aslan), Greenwald declares that Harris and his fellow New Atheists “have increasingly embraced a toxic form of anti-Muslim bigotry masquerading as rational atheism.” He holds that Harris and his cohorts “spout and promote Islamophobia under the guise of rational atheism,” driven by “irrational bigotry.”

Any rationalist critiquing Greenwald’s piece on Harris confronts a bewildering surfeit of material to refute, but essentially his argument turns on the term “Islamophobia,” which, as noted above, serves to exculpate the precepts of Islam and de facto shield the theological motivations of wife-beaters, genital mutilators, and honor killers. (Greenwald dismisses controversy over the term “Islamophobia” as a “semantic issue” that doesn’t interest him.) But as Harris has written, “If a predominantly white community behaved this way — the Left would effortlessly perceive the depth of the problem. Imagine Mormons regularly practicing honor killing or burning embassies over cartoons. Everything I have ever said about Islam refers to the content and consequences of its doctrine.” These words alone suffice to discredit Greenwald’s thesis.

Greenwald diagnoses Harris as suffering from “irrational anti-Muslim animus,” which leads him to view Islam as “uniquely threatening,” and even as “the supreme threat,” and to propound, as a result, “unique policy prescriptions of aggression, violence and rights abridgments aimed only at Muslims.” (This latter assertion he fails to substantiate with examples.) Criticism of religion, with Harris, “morphs into an undue focus on Islam.” For Harris, “Islam poses unique threats beyond what Christianity, Judaism, and the other religions of the world pose.”

Greenwald’s conceit is essentially that Harris, even when writing specifically of the misdeeds and crimes of Islamists, should presumably also remind us of, say, the Crusades and the Inquisition, as evidence that all religions produce equally bad behavior (when at this point in time — witness 9/11, Al Qaeda, Boko Haram, ISIS, and so on — they obviously do not.) In any case, according to Greenwald, Harris’ “irrational” obsession with Islam leads him to “justify a wide range of vile policies aimed primarily if not exclusively at Muslims” — most controversially, “anti-Muslim profiling.” In fact, “anti-Muslim profiling” is Greenwald’s sole example, so Harris’ “range” is not so “wide.”

Greenwald is referring to Harris’ blog post entitled “In Defense of Profiling,” in which he denounced the “security theater” we suffer through at airports before boarding flights, with its “tyranny of fairness” that has TSA agents subjecting, for instance, elderly, infirm, wheelchair-bound couples and the sandals of toddlers to the third degree.

“Some semblance of fairness makes sense,” Harris wrote. “Everyone’s bags should be screened, if only because it is possible to put a bomb in someone else’s luggage. But the TSA has a finite amount of attention: Every moment spent frisking the Mormon Tabernacle Choir subtracts from the scrutiny paid to more likely threats . . . . Imagine how fatuous it would be to fight a war against the IRA and yet refuse to profile the Irish . . . . We should profile Muslims, or anyone who looks like he or she could conceivably be Muslim, and we should be honest about it.” He adds that he could in theory fit the Muslim bill: “after all, what would Adam Gadahn look like if he cleaned himself up?” It follows, from Harris’ logic (and common sense) that if Mormons begin blowing up planes, Mormons would deserve close scrutiny when passing through TSA screenings. Note that what he is proposing amounts to reforming these procedures to reduce the sum amount of profiling, by making it more targeted on those statistically more likely to be terrorists, and less concerned with the rest of us — the vast majority, of whatever race we are.

Here we should pause for a reality check. Most Muslims are nonwhite; hence skin color inevitably figures among the features associated with “looking Muslim.” Yet the crucial factor is not race, obviously, but the potential for belief in the tenets of Islam that could prompt violent behavior, which leads Harris to include himself (and by extension, almost anyone) among the profile-worthy. That being the case, Harris’ profiling proposal would not eliminate the threat Islamic radicals pose to air travelers, but merely streamline undeniably cumbersome, time-consuming procedures necessary for our security and allow TSA agents to do their job more effectively. The increased efficacy would come at a cost to the perceptions of equity we hold dear. Yet no honest critic of Harris would conclude that mooting the subject in the way he does should result in charges of “irrational anti-Muslim animus” or “irrational bigotry.”

Absolved of the charges of racism, nuclear jingoism, and so forth, Harris has shown himself to be a committed public intellectual trying to help resolve the faith-induced crises of our time by dealing with their ideological bases and practical consequences. His “progressive” critics, in their efforts to becloud the causal relationship between belief and behavior, effectively provide cover for violent aspects of Islamic ideology, and are abetting the troublemakers and spreading confusion. Strikingly, they rarely, if ever, challenge Harris’ ideas, but instead opt to misrepresent them and denounce the resulting falsehoods. A decent concern for journalistic fairness — and the truth — is nowhere to be found in their works.

One cannot escape the impression that the attacks on Harris bear the stamp of sordid identity politics, with, under the guise of multiculturalism, truth sacrificed for the respect for retrograde customs. But perhaps what irks Harris’ detractors most of all is the methodical way in which he demonstrates the link between Islamic doctrines and terrorist violence, and disassembles the case for religion, showing, through his work, that it is nothing more than “a desperate marriage of hope and ignorance,” yet a marriage that could be annulled by “making the same evidentiary demands in religious matters that we make in all others.” (Both these quotes come from The End of Faith’s first chapter.) By extension, Harris’ arguments collide with the identities of people finding community in religion. If he were not succeeding in proving the case against faith, they and their apologists would not react to him with such vitriol.

An unwillingness to recognize the link between Islamic doctrine and terrorism in particular presages seismic political changes, with Western societies, fed up with Islamist violence and the inability of progressive governments to even speak frankly about it, lurching ever farther to the right. (This is happening in Europe today, of course.) But libeling Harris will not stop the next ISIS attack on Western soil, or slow that group’s depredations in Syria and Iraq.

Now more than ever, we need clarity on the relation between Islam and violence. And we need to stop denigrating those, like Harris, capable of bringing us that clarity.