US Election

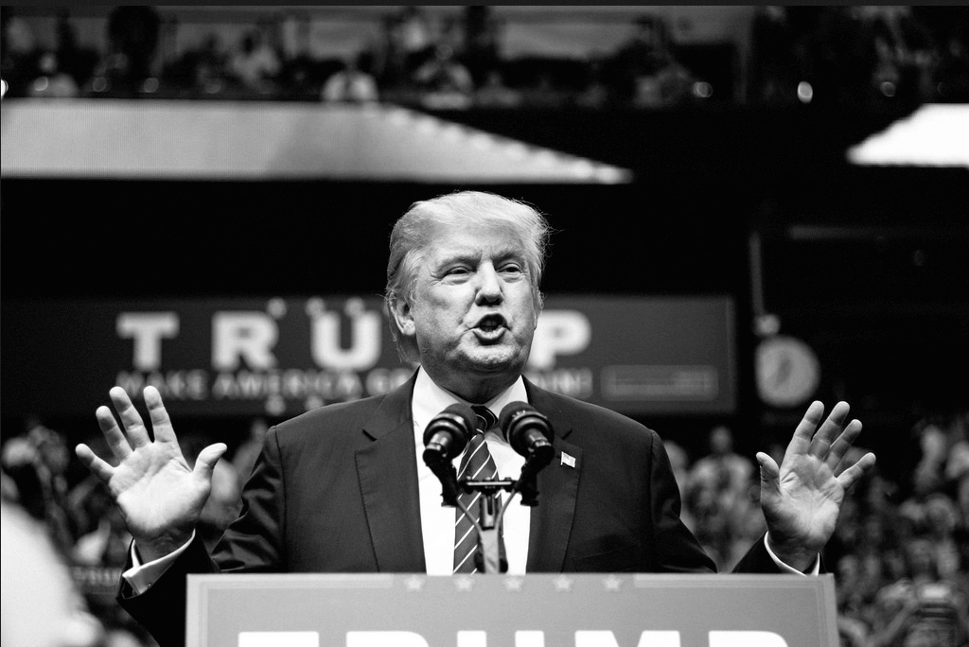

The Rise of Donald Trump

Trump has parlayed the fear, loathing, and restlessness of those who feel left behind by postindustrial America into an impressive presidential campaign.

I.

Since early February, Donald J. Trump, a brash and boorish businessman with a spotted past and tenuous fidelity to American conservatism, has dominated the Republican primaries, winning victories across states as disparate as Vermont, Hawaii, and Alabama. His opponents and much of the GOP establishment argue that he is vulgar, ignorant, and xenophobic—a comically stupid and coarse would-be Fascist who has no place in American politics. But to his many fervent supporters, these criticisms are at best irrelevant; at worst, they demonstrate the supercilious despair of the establishment and add to Trump’s outsider appeal. In the face of such denunciations from the powers that be, Trump keeps winning. At the ballot box—winning. On television—winning. In Twitter battles—winning. And the polls suggest he will keep winning so long as his rivals remain divided.

To some, his rise is evidence of the racism that hides beneath the veneer of polite society in America. Certainly, he has voiced some disconcerting opinions; and he has aroused the support of some unsavory political figures. Quite possibly he is, in fact, bigoted. But the real source of his appeal, we believe, lies in the refuse of postindustrial America where the White working class struggles for esteem in a rapidly changing, multicultural society.

Imagine that you were born in a modest Prairie style home in small town Kentucky. Beyond the shadows of the maple trees that surrounded your house, farmland stretched down the highway, interrupted only by small Country homes with white fences, bright gardens, and sunny porches. After high school, you stayed in your hometown and had a family. But jobs were difficult to find. In your father’s day, there were plenty of good manufacturing jobs. But those had left. And the town was changing. The houses that you remembered as warm and sunny were now faded with rotting fences and unkempt lawns. Buildings that used to house hundreds of workers were empty and dilapidated with shattered windows. After a long struggle, you found a job at Pizza Hut making 9 dollars an hour. It wasn’t enough to support the family, so you began to supplement it with government assistance.

You had been a Republican for many years because you thought it was important to talk about God and to discourage free riders from taking advantage of the country. Furthermore, you believed in traditional marriage and family values. But you had been growing more and more frustrated with Republicans as the years passed. In magazines, in films, and on television, people openly denigrated your culture, ridiculing rednecks, hillbillies, and bible thumpers. NASCAR, your favorite sport, was still mocked by suburban elites. And Walmart. And country music. And the military. And action films. And smoking cigarettes. And chewing tobacco. And eating meat. You despised the so-called experts who were always telling you how to live your life, the film critics who were always sneering at your favorite films, and the haughty politicians who were always lecturing you about tolerance.

Things were getting worse. You knew several people who had lost their jobs to Mexican immigrants who had just arrived in your town. You heard many more complaining about this on the radio, lamenting that immigrants had replaced them at the factory. Many of those immigrants were probably in the U.S. illegally. Why did the police and the government allow rich business owners to use cheap, illegal labor when so many Americans were out of jobs? You didn’t hate Mexicans, but it did perturb you that many of your phone calls asked you if you wanted English or Spanish. Wasn’t this an English speaking country? But nobody cared about your concerns. In fact, on television, you heard many commentators calling your opinions bigoted and racist.

And free trade deals. They were causing jobs to relocate to Mexico, to China, to India. Whenever you had a problem with Comcast, for example, you now had to talk to somebody in some other country, somebody who struggled with English and was not very helpful. Apparently, politicians just didn’t care about Americans anymore. Both Republicans and Democrats seemed to promote free trade and even some kind of immigration reform. You wondered: Why should millions of people who broke American laws, who stole American jobs, be allowed to stay here, to get taxpayer supported handouts, to become American citizens? So, that was it—your town would continue to decay while politicians continued to pursue policies that hurt you and everyone you knew. And worse still, you weren’t even allowed to say anything about it—weren’t allowed to voice your real political opinions—without being denounced. If you were white, what did you have to complain about? You were privileged. You weren’t a victim. It was time you had gotten with the program. Embraced diversity. And stopped complaining about lower wages, fewer jobs, and changing cultural norms.

II.

For many Americans, the Kentucky described above is as foreign as a remote tribe in the Amazon. Over the last 50 years, in what Charles Murray refers to as the “coming apart” of America, an enormous cultural and geographic chasm has opened between the educated cultural elite and the White working class. In large cities, suburbs, and college towns across the country, millions of educated people interact in an ethnically diverse world. Oblivious to the declining living standards of relatively low-skilled White workers and the decaying towns and cities they call home, the educated elite enjoy the fruits of post-industrial America.

People from this pool of educated, cosmopolitan elite now occupy most positions of power and influence in the United States, including in both major political parties. And they have shaped society in ways that largely reflect their own interests and values. In a sense, they have created a cognitive niche that is inhospitable to many Americans. They have also promoted and enacted policies that are either indifferent to the plight of lower White America or that actively contribute to it. Most of the political elite, for example, support free markets, low taxation regimes, international trade deals that are tilted toward the wealthy, anti-inflationary monetary policy, capital mobility, and reasonably open borders, especially for low-skilled immigrants.

Perhaps more importantly, educated elites have extinguished the esteem of lower White America—they have derided most of its cultural values, and have promoted a species of political correctness that righteously denounces any deviations from a “diversity is great” catechism. The educated elites not only abstain from drinking cheap beer, such as Budweiser or Miller, but they also denigrate it. They are often haughty, and openly mock those who do not appreciate the subtleties of David Fincher, Jonathan Franzen, or Larry David. Among these elite, once popular television shows such as Full House and Two and Half Men are ridiculed as simplistic and puerile. Even more violently ridiculed—and morally condemned—are complaints about immigrants or diversity. Cultural elites benefit from immigration and from diversity. They enjoy the new ideas, new foods, and new experiences that multiculturalism offers. And they aren’t directly competing with low-skilled immigrants for jobs.

This chasm between the cultural elite and lower White America is why you might feel mocked by the mainstream media if you were born, raised, and reside in small town Kentucky. It is why you might feel betrayed by the political establishment. It is why you might be filled with anger, fear, and resentment. And it is why you might support Donald Trump.

III.

Imagine, again, that you are that person from small town Kentucky. You had become disenchanted with politics and with political parties. None of the politicians—not John McCain, not Barack Obama, not Mitt Romney, not Jeb Bush—talked about your problems. Obama even explicitly criticized you and people like you, sneering that you cling to your guns and your religion because you are afraid of the modern world. But then a candidate, who completely eschews political correctness, entered the presidential race. Donald J. Trump. Billionaire. An incredible success. And he started to talk about the problems you care about.

In his announcement to run for president, for example, he addressed immigration. “When do we beat Mexico at the border? They’re laughing at us, at our stupidity,” he contended. And he declared that America has become a wasteland, pointing out that “Our country is in serious trouble. We don’t have victories anymore.” That sounds exactly right. And we don’t have victories because, “The U.S. has become a dumping ground for everybody else’s problems.” We don’t have victories because we negotiate colossally stupid trade deals with China and Japan, whose leaders absolutely “kill us.” In speech after speech, Trump assured you that he “will make America great again,” because he knows how to win and isn’t a part of the cartel of Washington politicians who have created and then ignored your community’s plight and disintegration.

As Trump became more popular, the media denounced him more feverishly. Other politicians denounced him just as they denounced you. And this convinced you that he was even more important and more committed to the causes you care about.

The establishment—all of the people who have mocked you and your culture—is trying to stop him because they are afraid of him. They know he will shake up Washington and restore the prestige of your community. Sure Trump has flaws. He can be crude, insensitive, and vague. But at least he says what he thinks. At least he is not a cautious politician. And at least he isn’t bought and controlled by special interests.

IV.

But is this lower White American anger and alienation actually the source of Trump’s support? The data suggest that it is. Although Donald Trump is relatively popular among many groups of Republican voters, he is most popular among those who resemble, demographically, the person from Kentucky described in sections I and III. In exit polls and surveys, white men without college degrees, more than any other demographic, prefer Trump. In past primaries, he won by huge percentages in economically devastated communities such as Fall River, Massachusetts and Macon County, Tennessee.

Perhaps because of these demographics, and because of some alarming things Trump has said, some people have suggested that Trump’s supporters are impelled by intolerance, bigotry, or authoritarianism. Trump, they argue, has traded the traditional racial dog whistle for an unapologetic alarm and is assembling a white nationalist party of disgruntled southerners who still lament the loss of the civil war.

Although popular and reassuringly Manichean (Trump and his supporters are evil), the narrative of Trump as a would-be rebirther-of-the-white-nation is seriously flawed. On the one hand, it fails to explain why Trump would vaunt endorsements from several prominent African Americans, including Dr. Ben Carson. On the other hand, it fails to adequately explain available data about Trump’s supporters. To say that this narrative is flawed, is not to say that racial tensions and hostilities are irrelevant to an explanation of Trump’s rise—we are talking about working class White America, so race is germane. Rather, to call this narrative flawed is to suggest that if we stop at racial politics we’ll fail to understand much of what animates Trump’s supporters.

In exit poll after exit poll, Trump’s supporters inform us that they want an outsider—that they want somebody to tell it like it is; that they feel betrayed by the GOP; and that they are angry with the government. Furthermore, a Washington Post survey found that Trump’s supporters strongly mistrust experts and believe that elites control the political system. And although these supporters scored high in Authoritarianism, they scored no higher than Rubio or Cruz’s supporters. This evidence seems consistent with the hypothesis that alienation, disenchantment, and rage are driving Trump’s supporters: They want an outsider because they are angry with a government that has left them behind. They feel betrayed by both political parties, but they feel especially betrayed by the GOP, whom they had supported and expected to enact favorable policies. They don’t trust experts or other cultural arbiters of taste. And they feel as though Washington is run by a small coterie of elites who routinely ignore the will of the people.

A Trump supporter summarized this frustration quite well in a letter to the Atlantic:

Deep down many Americans know our country is in a state of total failure. That’s true for folks on the left and right. We know that our futures have been sold and that our children’s futures have been sold. We know that every politician we have to choose from is a liar and a flip-flopper.

It’s also telling that many of Trump’s supporters profess admiration for his proclivity to call it as he sees it. Trump, they believe, is authentic. And he won’t be silenced by the stale pieties of political correctness. He is willing to stand up for White people and to push back against policies that have gutted the White working class. For many of these White working class Americans, there is a strong perception that minority groups are being peculiarly attended to while other Americans are allowed to slide into economic and social misery. As one Trump supporter put it, “…no one’s looking out for the white guy anymore.” Another noted, in reference to the Black Lives Matter movement, that, “All lives matter. You know this is bullshit about black lives matter—doesn’t [sic] all lives matter?”

V.

Saturday Night Live recently released a video in which several white people forwarded their reasons for supporting Trump. “He tells it like it is,” one said. “He literally wrote the book on negotiating,” another added. As they spoke, the camera zoomed out to show some unmistakable sign of racism such as a Swastika or a white Ku Klux Klan suit. Funny, yes. But almost certainly misguided and counterproductive. Many of Trump’s supporters are already convinced that mainstream America is against them. They believe, with justification, that they are mocked and ridiculed. And they are especially indignant that they are not allowed to voice their concerns about immigration, about Black Lives Matter, and about globalization and multiculturalism more broadly, without being called racists or bigots.

Instead of mocking Trump’s supporters, it would be useful (and morally decent) to understand them and their complaints. It is easy for the educated to dismiss concerns about free trade as ignorant nationalism, to chastise concerns about immigration or terrorism as repugnant racism, and to ridicule concerns about elite collusion as paranoid conspiracism. Easy. But perhaps not wise. The White working class has, in fact, struggled for many years. And they are legitimately angry. Although the reasons for their struggles are myriad, many experts do believe that free trade deals and immigration policies have contributed. Reasonable people might decide that the costs of trade deals and lenient immigration policies are vastly outweighed by their benefits, but to deny those costs, is not to promote social harmony or justice. And to accuse of mindless xenophobia those who have been hurt most by such policies, is probably far worse—and quite possibly, completely counterproductive.

Trump has parlayed the fear, loathing, and restlessness of those who feel left behind by postindustrial America into an impressive presidential campaign. He may be detestable, but so long as cocooned elites ignore the anxiety he has channeled, he will keep winning.