History

A Memoir from Mesopotamia

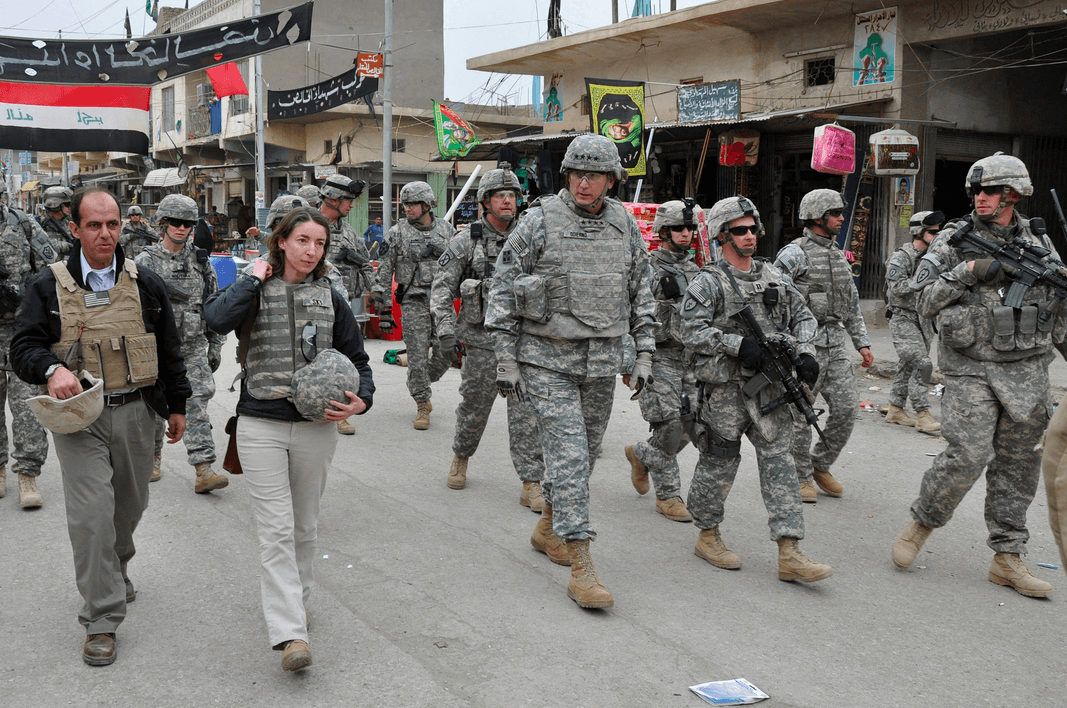

The book documents the years she spent in the country, working closely with the American military.

Emma Sky’s memoir of her time in Iraq captivates. Her account, as a British, female, one-time opponent of the Iraq war, deals with how she administered an Iraqi province in the aftermath of the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. The book documents the years she spent in the country, working closely with the American military — the same organisation she and many like-minded individuals opposed so vigorously in the run up to the war.

In the latter role, Sky became associated with what she calls the ‘American tribe’ (despite being a British citizen with little formal guidance from her own government), serving as a political advisor to American officials including Raymond Odierno (‘General O’) and David Petraeus. A great deal of the memoir consists of the realities of administering a newly-liberated nation, with dramatic descriptions of the work the military undertook, the realities of working in a warzone, and interesting dissections – complete with reproduced emails and recalled conversations with key participants – of rebuilding a state and attempting to create the underpinnings of a functioning democracy in the most trying of circumstances.

Sky’s assessment of divisions and rivalries within the Coalition is built upon her close knowledge of the personalities involved. She was insulted by colleagues on her birthday, witnessed at first hand the conflicts between civilian and military operations within the Coalition, and recounts vital details about how things were really decided. The latter minutiae can be (perhaps unexpectedly) fascinating, as who was sitting in which meeting, and what exactly was said, became a vital element of how the country of Iraq was rebuilt.

But Sky’s assessment is not just a recollection of administrative life within the Coalition. The book is also an extended assessment of the merits and failures of the reconstruction of Iraq, as well as a wider look at the other factors – namely Iranian involvement and domestic politics in the United States – which contributed to the titular collapse of what had been, for a short time, a hopeful situation. (On Iran, Petraeus was declarative: ‘They’ll pocket what we give them, bide their time and come back more lethal.’)

Certain aspects of Sky’s writing – particularly about the Sahwa (‘Awakening’), which helped to unite Iraqi Sunnis against al-Qaeda in Iraq – are thoroughly affecting. As are some of Sky’s other assessments of the situation: the Surge of 2007, which dramatically increased the number of American troops in the country, also helped, in her view, to stabilise some of the more volatile aspects of the post-Saddam state of affairs.

Sky’s perspective is an idiosyncratic one – and her atypical background (being both British and female, as well as having opposed the war) create some tensions within the text. Luckily for the reader, however, these also allow for an especially acute analysis, one which is detached from vested interests and storied regimental histories. Her personal perspective brings to life much of what other writers might have missed (or mistakenly deemed unimportant). Yet it is preserved: showers which are minutely scheduled, absurd acronyms which became commonplace, and the increasingly strange spectacle of what US troops are compelled to watch on television. Sky builds up a truly comprehensive picture of the Coalition, which was more than the sum of its military victories and defeats, and more than a collection of half-forgotten diplomatic initiatives.

Sky’s book contains, more than anything else, a genuine appreciation of Iraq. This is seen in the affectionate way she describes the personalities of the country’s various political and religious leaders, and in the impressive, empathetic way she details her experience with many Iraqis. It is apparent to see how much she valued and continues to value contact with Iraqis – both ordinary citizens and government figures – and not difficult to see why. Stories of her travels around the country, often without a military escort, radiate humanity and serve to bear witness to her personal investigations regarding Iraqi society itself.

Sky never sits by idly; she is an active presence. And she allows both Iraqi and American personages to speak for themselves – something which is sorely lacking in some more academic and analytical efforts. The resultant work is an effective, enthralling memoir which doubles as a panoramic and ultimately unresolved portrayal of a country – and a region – which struggles fitfully towards the prospect of democracy.

Much is made – by both Western journalists and Iraqi politicians – about the apparent resemblance between Sky and Gertrude Bell, whose influence on the foundation of Iraq cannot be overstated. Reading the former’s accounts of her time in the country, this comparison seems even more apt – with one alteration: unlike the Bell of reference, but not unlike Bell as she truly was, Emma Sky is not only a governor but a writer, and a thoroughly compelling one at that.