Reluctance to Bomb Daesh Reflects a Loss of Confidence in the West

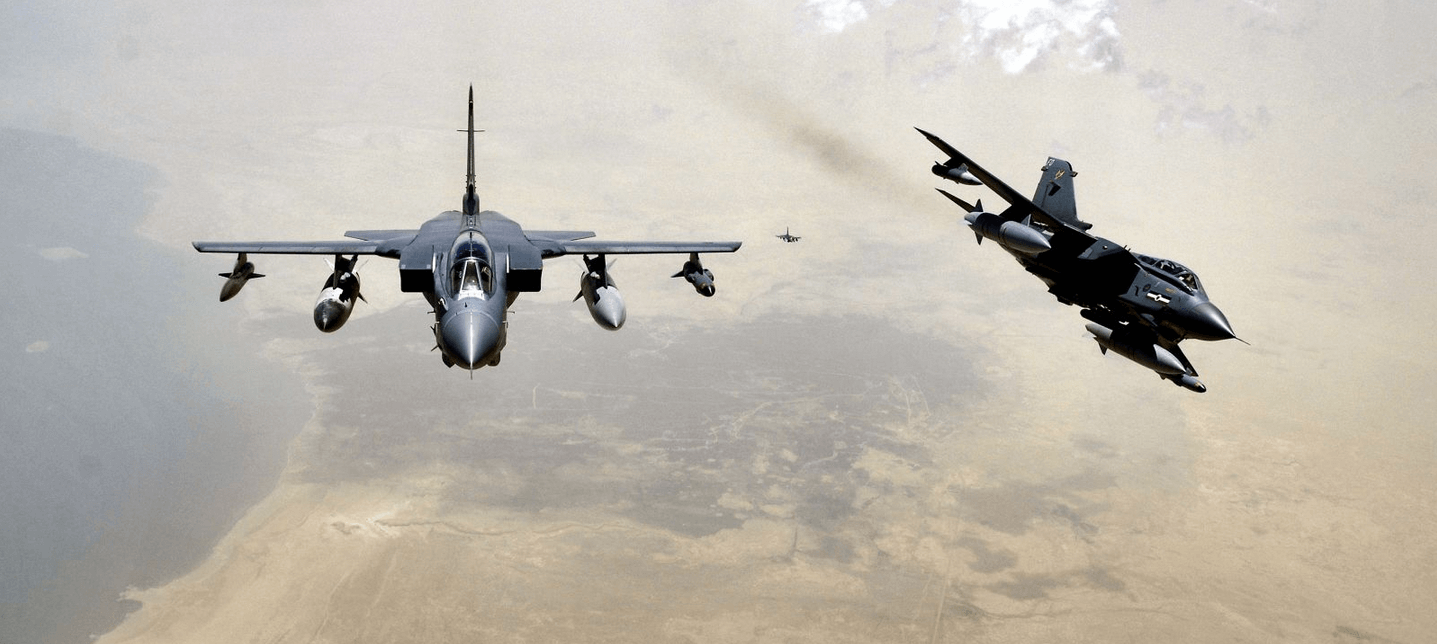

The UK has begun bombing Daesh in Syria. As the first Brimstones hit home mere hours after the vote passed, the only certainty is that there’s no knowing how many will follow in their path.

The UK has begun bombing Daesh in Syria. As the first Brimstones hit home mere hours after the vote passed, the only certainty is that there’s no knowing how many will follow in their path.

When and in what circumstances Operation Shader will conclude will also remain unclear. For the meantime, however, the very nature of the Parliamentary debate and vote itself presupposes a number of conclusions:

- Interventionism is dead. Long live the new interventionism. The express intention to avoid occupying ground was a more central factor in the vote passing than any other, but the appetite to take active role in a general sense is still strong;

- The Middle East will remain the lynchpin of how global (in)stability is measured. Despite major conflicts in Asia and Africa, not to mention Ukraine, the Middle East remains the central proving ground for world powers;

- The West lacks the internal unity, external political power and moral clarity necessary to impose its will, and thereby mould a satisfactory end to the Syrian conflict.

During the debate, David Cameron appeared hamstrung by difficult questions, while Jeremy Corbyn was principled only in his resistance to deal with reality; both the reality of the state of the Labour benches behind him and in the world outside.

Hilary Benn, meanwhile, was opportunistic in his impassioned advocacy. More on the former leader’s son later.

The vote passed, with 397 MPs in favour of airstrikes and 223 against. A convincing majority, but it’s easy to forget that the vote on approving initial air action against Daesh in Iraq passed with far less turbulence back in 2014. In that vote, 524 MPs were in favour and only 43 against.

What was behind this dramatic reduction? Approving operations in Iraqi skies was a political no-brainer. The situation there is far less complex, Daesh aren’t the only bad actor in the country, but the line from British bombs to peace could be far more smoothly drawn.

Jeremy Corbyn’s opposition may have convinced some on its merits, however the shift of 180 MPs cannot be credited to someone who couldn’t even whip a party line.

Even though the majority of no votes would be described as coming from the left, the lack of a greater plan for unlocking the Syrian conflict at large shifted even the most confident yes vote towards some uncertainty.

If Iraq was simple, Syria is the opposite. Fly across the non-existent border, and all of a sudden there’s the distinct feeling that there’s no overarching plan to defeat Daesh, whereas a few miles away, over Iraqi sands, it all seemed so clear.

There is only one person responsible for the uncertainty, which manifested last week in British MPs opposing the call to oppose Daesh in their heartlands. Barack Obama stands with the ball dropped at his feet, his red lines dots in the past.

At a time that it is needed more than ever, the presence of strong US leadership in the world was completely absent from the debate. Cameron was left to invoke the promise of a multilateral political settlement (read: Russian dictated settlement, which is no settlement at all) to justify beginning what could otherwise be an endless air campaign. On the left, Benn called on Labour MPs to come to heed the call to arms from fellow socialist Francois Hollande. If John McCain’s response to the UK strikes in Syria was blunt, Obama and Kerry didn’t merit a nod in Parliament.

Deservedly so. The debate of whether the UK should target Daesh in Syria is coming years too late, and the lack of progress on a broad strategic front more a pipedream than a Boris Island airport.

While Daesh are more than worthy targets, Assad stands at the very centre of the carnage. Around 90% of the (at least) 300,000 deaths and millions of refugees can be traced to his actions. With him in power, the slaughter will continue. Islamic extremism all over the region thrives off of the continued injustice of his rule.

What’s more, Assad was and remains fundamental in the rise and success of Daesh themselves. Bombs over Raqqa will be blunted by the political reality on the ground: Assad, Russia and Iran are firmly in control of the cards. While they are, the violence will only stop when there’s nobody left to replace the Alawite dictator.

To prove this point to a painful degree, the YPG, an element of the Syrian Kurdish forces central in Cameron’s calculation that there are 70,000 allies on the ground, are in the regime’s pocket. Thanks to Russian and Iranian influence, the YPG have as recently as this week been working in tandem with Assad and Daesh to attack moderate rebel forces in Aleppo.

For the situation to be so far out of the hands of the West and their allies is a betrayal of the responsibility the US in particular has to ensure bad actors in the region such as Iran cannot expand their destabilising influence.

The West needs to take the initiative, and that means finding a way to turn the pieces of this fragmented conflict in their favour. One example: force a cessation in Turkish-Kurd violence and Turkish acceptance of Daesh oil. The lack of US influence in these instances has allowed two vital allies in fighting Daesh and ending the conflict into almost counterproductive players.

A broader goal would see the West and their wider allies form an official military coalition of agreed aims and committed contributions, organised and determined to impact the dynamics on the ground as a whole, and not just Daesh oil convoys.

France and other states’ flirtation with cooperation with Russia and Iran betrays a general despair. If it is to truly play a constructive role in the future of Syria, the West and its allies must become the central pillar around which all the other elements rotate. That leadership and vision went missing the day Obama didn’t bomb Assad, all those years ago, and hasn’t reappeared since.

Back to the UK, and onto the shadow foreign secretary, the new darling of the centre. Hilary Benn should perhaps not be trusted as an authentic voice, as he seems to suffer from an identity crisis.

Despite extolling the virtues of British action in Syria, and correctly rejecting his leader’s fears that strikes would inevitably lead to more terror, last year Benn absolved Hamas’ guilt for the kidnap and murder of three Israeli boys, which led to a spiral of violence he then blamed on Israel.

In the dreadful scenario of a successful Daesh organized attack on British soil in the coming months, it would be difficult to envisage Benn criticising himself as he did Israeli leaders for attacking a similarly genocidal terror organisation, which murders people based on their identity and values.

Reading over Benn’s apology for Hamas terror reminded me of Ken Livingstone explaining the “context” for why on 7/7 terrorists in London decided to “give their lives”.

While Hamas and Daesh may be very different in some respects, if the newfound star of the Labour moderates thinks one liberal democracy should be singled out for reacting to terrorism and defending its civilians, while another can fly halfway around the world to combat a similar evil, he’s confused, at best.

Benn lampooned Israel for causing collateral damage, but regarding Syria, the issue received only fleeting mention. The UK, you see, doesn’t intend on hurting civilians. So that’s that.