Art and Culture

On Privilege and Being Human

Our intellectual ascendency defined us as a species and is inextricably linked to our success and our ability to connect with one another.

Thinking itself is the privilege of being human. Our intellectual ascendency defined us as a species and is inextricably linked to our success and our ability to connect with one another. Everything that nature can bestow upon us in our human lifespan is also a privilege: intelligence, youth, a healthy mind in a healthy body. The most basic human rights that we take for granted are, in reality, privileges afforded to the most fortunate members of our species: adequate shelter, a clean water supply, an education and freedom.

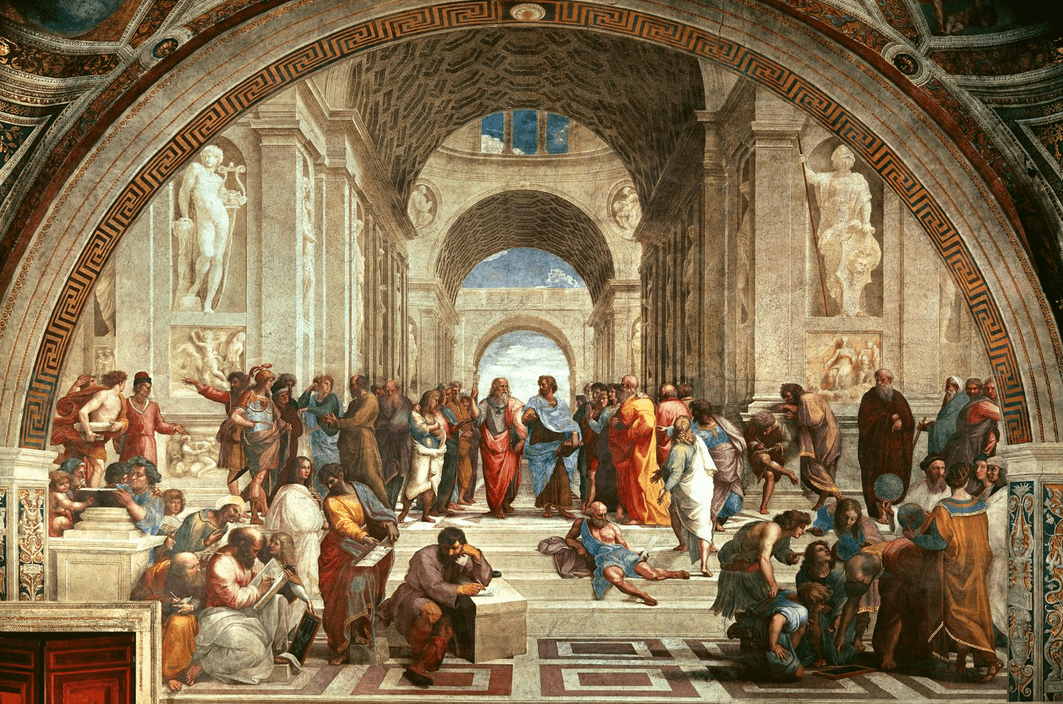

As Aristotle acknowledged, it’s impossible to avoid the fact that a basic level of comfort is usually necessary to facilitate any real freedom of thought. If every scrap of our energy is spent upon basic survival or averting imminent disaster, there is precious little time for navel-gazing. Genius though he was, Aristotle’s world was culturally narrow in comparison to ours; yet he realised that the times he spent frequenting the shady colonnades of the gymnasiumwere opportunities afforded to him as a result of his privileged lifestyle – not everyone’s experience of life was aligned with his own.

Freedom of thought is essential to progress in society, although there is no denying that their own silence might be the best gift that some individuals could extend to humanity. The disadvantage of unfettered free speech is that at some point we end up listening to Bernard Manning; we’ve all been there, making agonised small-talk at a work-based Drinks Do or trapped in a cab with the driver who thinks “you can’t say anything these days, can you?” Well, if every single thought in your head is racist, homophobic or misogynistic then maybe so, although in my experience such people seem to manage it anyway, usually at high volume.

But the relative truth that some of us may have “privilege” over others has recently become a weapon to be wielded against the freedom of thought that we all deserve – whatever our privilege. The idea that one should “check one’s privilege” is a recent off-shoot of “political correctness” that was comparatively benign in origin: don’t assume that you know how someone else feels or claim that you understand their struggle unless you’ve “been there” and be worldly enough to acknowledge the distinct and self-evidential advantages that you may enjoy as a result of your racial origin, your economic and social demographic, your sexuality, your gender … the list continues as far you as you wish to stretch it.

So far, so fine and noble. Quite frankly, it’s obvious advice that applies to all of us who aren’t fighting over half-rotten scraps of food on waste-ground, or living in fear in a war-torn, famine-ravaged part of the world.

But too often the exhortation to “check your privilege” is brandished as a cudgel against anyone who is deemed to have any kind of authority or prestige, with little or no consideration given to how they might have attained that position. You’re an Emeritus Professor, successful author and pivotal figure in second wave feminism? Check your privilege. You’re a Nobel prize-winning scientist? Check your privilege. You’re an Op-Ed journalist with a national broadsheet? Definitely check your privilege.

But far worse than knocking those who have achieved something in their lives, the most dangerous by-product of this facile notion of privilege is the sense of victimhood that it affords people. Nobody wants to be a victim and nobody should feel like one. Why should the relative disadvantages that an individual may have faced define their sense of self? Why should they be granted nothing more than the damaging legacy of all-consuming resentment?

Everyone has their own demons, and those demons can work for or against us. We can use them to enable us to leap into someone else’s shoes and to entertain the notion that they too may have faced a struggle, perhaps greater than our own – or we can let them rule us and shut us down. We can employ our personal experiences to make allies and to connect with other people, or we can carve up society even further by pretending that the only people who can understand us on any level are those with an identical lifestyle – taken to a logical conclusion, that adds up to nobody.

When the counsel to “check your privilege” is used as a bludgeon rather than a gentle reminder that we each have our own perspective on the world, it drives potential allies away from the people who need them the most. It also belies the very concept that empathy is even possible – and without empathy, we lose our humanity and each other.