Art and Culture

Strange Delight

Radley Metzger’s 1975 hardcore adaptation of a celebrated literary hoax is a vast improvement on the cynical source material.

I.

Last year, Radley Metzger’s 1975 hardcore classic Naked Came the Stranger was re-issued by US indie distributor Mélusine in a lavish 50th anniversary package, complete with a glossy booklet and a wealth of extra features, including a commentary track recorded with Metzger shortly before he died. In the age of streaming, the care and attention given to this physical media release feels oddly retro. The movie itself, though, feels nostalgic, and in a way that modern liberal viewers may find faintly scandalous.

The film’s protagonist is a radio personality named Gillian Blake (Darby Lloyd Rains) who hosts a morning chat show with her husband Billy (Levi Richards). After she discovers that Billy is having an affair with their production assistant, Phyllis (Mary Stuart), Gillian tries to reignite the erotic spark in her marriage by sleeping with a number of men. She is not outraged by her husband’s infidelity nor even angry—on the contrary, she’s excited by his ability to seduce another woman. But she is also perplexed, and so she embarks on her mission to discover how she might recover his erotic longing—no small feat for a couple who share domestic duties, work responsibilities, and the nightly wind-down routine of TV and reading before bed. She doesn’t cheat on Billy to even the score (at least not primarily), but rather to find the “inner man” in other men so that she can see it anew in her husband.

Metzger charts a woman’s journey to rediscover erotic desire in her marriage. Its catalogue of faithlessness notwithstanding, it is actually a hopeful and oddly conservative story of marital fidelity. I am unsure if an erotic marriage is something that many married women still desire. College-educated women, in particular, talk more about things like equality, respect, and mutuality. We demand these things from our partners and sternly correct them when they fall short. We want a “healthy sex life,” and we insist that this has something to do with frequency, “open communication,” and reciprocity, as though a scoreboard and calendar might be good measures of hot sex. But Metzger shows us that it is precisely Billy’s strangeness that makes him attractive to his wife, not just his divergent desires, but also his very separateness from her.

“Inner men,” Gilly discovers, want more than just sexual gratification. They want to feel a sense of their charm and potency as men. This does not mean that a man’s inner desire is simply to have lots of sex as much of today’s pornography suggests. A man wants to be loved for being a man, not for being male. He wants his sophistication, his position relative to other men, and his confidence to be admired. This is not mere virility; it is the fruit of cultivation. He wants warmth from a woman and to feel uniquely desired. There is no scolding in the film, no need to correct the desires and behaviours of men, not even their indiscretions. Nor is there a sense of pandering to what is low, tasteless, and vulgar. The film has a sweetness alien to most pornography and an endearing silliness seldom found in erotica. I don’t quite know what it is.

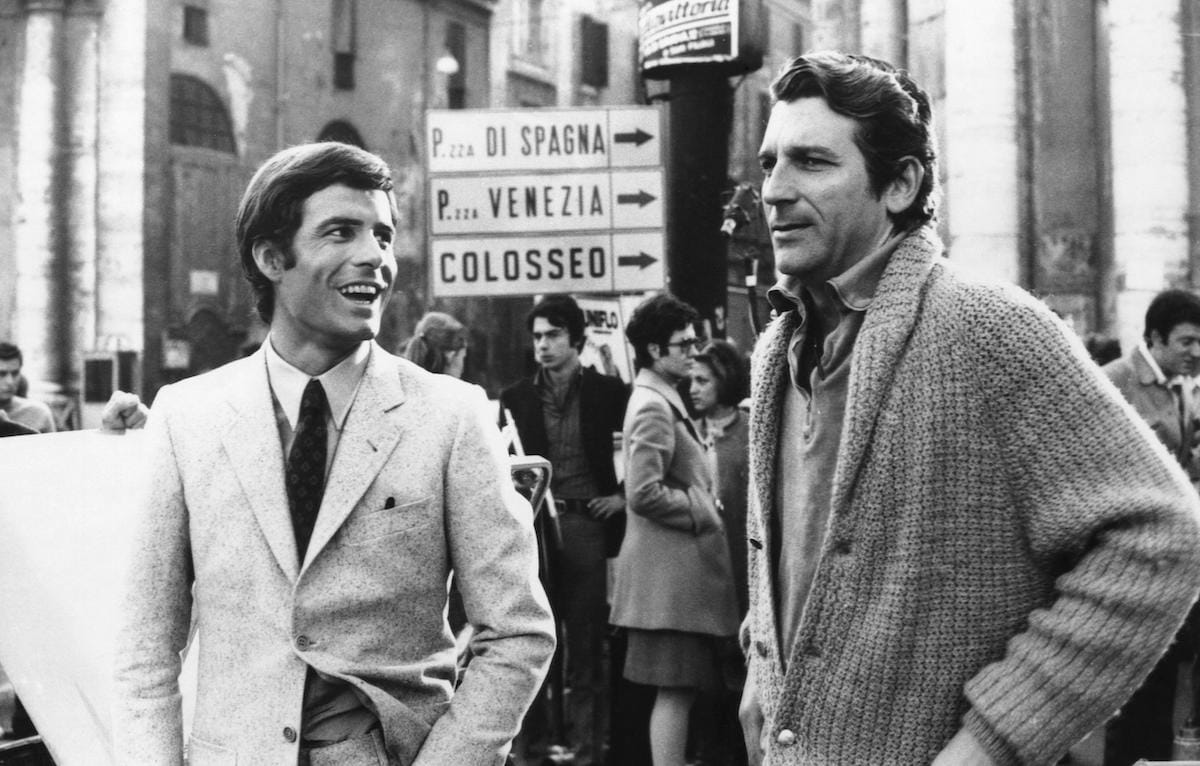

But then, Radley Metzger was an idiosyncratic director. He began his career in the mid-1960s shooting low-budget “nudie cutie” films, although even these early works betrayed an artistic sensibility that allowed them to transcend their exploitative trappings. Those minor pictures were followed by a brace of tasteful and lightly erotic literary adaptations (of Prosper Mérimée’s 19th-century novel Carmen in 1967 and Violette Leduc’s 1966 sapphic boarding-school romance Therese and Isabelle in 1968). He closed the decade with Camille 2000 (1969) and The Lickerish Quartet (1970), two stylish works of psychedelic Euro softcore cinema, shot in Italy and then dubbed into English.

Metzger ventured into hardcore filmmaking four years later, shortly after Behind the Green Door and Deep Throat kickstarted a short-lived highbrow interest in porno chic. His 1973 sex comedy Score is an adaptation of an off-broadway play about bisexual swingers that featured simulated scenes between the two women and a handful of unsimulated scenes between the two men. He would make just six more hardcore features, all of which he would write under the pseudonym “Jake Barnes” and five of which he would direct under the pseudonym “Henry Paris.” Naked Came the Stranger is the second of his Henry Paris pictures, and a more experimental offering than its 1974 predecessor The Private Afternoons of Pamela Mann, a kind of companion piece that also deals with marriage and infidelity.

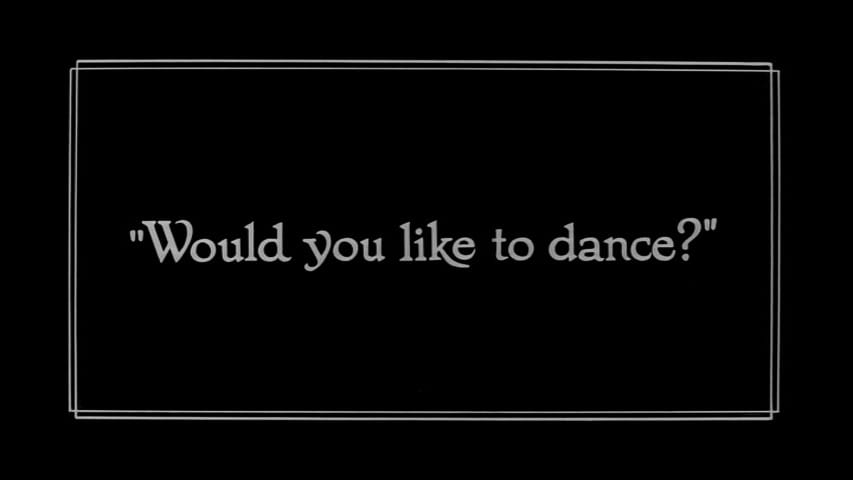

Let me take a moment to describe an instance of Naked Came the Stranger’s weirdness. About fifty minutes into the film, we are suddenly given a twenty-minute seduction scene presented in the style of an old silent movie, shot on monochrome stock, complete with dialogue intertitles and the sound of the celluloid clattering through the projector gate. It is an elegant sequence, and occasionally funny in surprising ways. At one point, after a romantic dinner, Gillian’s seducer (Gerald Grant) asks in silent-movie print, “Did you enjoy lunch?” to which she shakes her head and mouths the word “No.” But the intertitle reads “Yes” (which is what she ought to have said according to convention). This is nothing more than a cute wink and a giggle, but its effect is charming. Metzger’s film is filled with postmodern asides like this one that momentarily disarm us and make us aware of the film as a medium. They flatter us by making us feel that we are in on the joke, which creates a sense of intimacy with the performers quite different from the voyeuristic gratification customary in pornography.

The effect of this scene is disorienting and wistful, and I find myself oddly moved by the film’s nostalgia for a time when the social role of a man was distinct from that of a woman. This is not a Mad Men-esque exploration of the fraught gender norms of the 1950s and ’60s. It is a love letter to the complementarity of the sexes and of their distinct social roles. And it is refreshingly free of the resentment, rancour, or envy now typical of almost any discussion of gender or sexual politics. At bottom, Naked Came the Stranger is about how being strange to each other as socially gendered creatures is a gift rather than an injustice to overcome.

II.

Most interesting of all, perhaps, is the casual generosity with which Metzger navigates this material: like Pamela Mann before it, Naked Came the Stranger is a film about being in love with and devoted to the person you’ve married. This is unusual—and in its own way transgressive—for a piece of pornographic cinema, but it is particularly surprising given the mean-spiritedness and cynicism of the movie’s source material.