Health Care

The Canadian Paediatric Society Is Trapped in a Pre-Cass Time Warp

While other jurisdictions adopt balanced, evidence-based protocols for treating gender dysphoria, the CPS has doubled down on an obsolete policy instructing doctors to reflexively ‘affirm’ trans-identified youth.

This essay was adapted by Quillette’s editorial staff from The Cass Review and Gender-Related Care for Young People in Canada: A Commentary on the Canadian Paediatric Society Position Statement on Transgender and Gender-Diverse Youth, published in Archives of Sexual Behavior on 21 November 2025. An abbreviated version had appeared as a Letter to the Editor in Paediatrics and Child Health, to which the authors of the below-referenced Canadian Paediatric Society Position Statement replied. Readers are invited to refer to the original publication for additional detail and additional references.

In the debate over the use of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to treat transgender-identified minors, proponents of the “gender-affirming” care model find support in the position statements published by North American medical and mental-health associations. This appeal to authority offers a convincing argument. Doctors, policy makers, judges, journalists, and the public-at-large tend to rely on the scientific and clinical expertise within major professional organisations to review and evaluate complex scientific evidence.

However, the reliability of these official statements was challenged when Dr Hilary Cass delivered her comprehensive 2024 report to National Health Service (NHS) England. That document, often described as the Cass Review, detailed the “shaky” evidentiary foundations undergirding gender medicine for youth. It has led to the NHS making major changes to its policies on treatment of gender dysphoria in children and adolescents. While the Cass Review investigated practices in NHS England, its findings on the evidence base are relevant around the world.

The Canadian Paediatric Society’s 2023 Position Statement on this issue, entitled, An affirming approach to caring for transgender and gender-diverse youth, is one of the official statements that urgently requires reconsideration in light of the findings of the Cass Review.

This Position Statement—authored by Drs Ashley Vandermorris and Daniel L. Metzger, under the auspices of the Canadian Paediatric Society’s Adolescent Health Committee, recommended that health care providers “adopt an affirming approach” when presented with a trans-identified child; that “increased training on affirming care should be integrated into paediatric and paediatric subspecialty training programs across Canada”; and that “gender-affirming care must be upheld as standard of care” for trans-identified and “gender-diverse” youth.

The affirming model that the Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) Position Statement endorses is based on the assumption that gender-identity development in young people is linear and stable. Although the CPS Position Statement indicates that gender identity evolves, it makes no mention of the detransition and desistance literature, or of the mental health comorbidities that may impact gender identity. (A “detransitioner” is a patient who stops gender transition after taking medical steps such as hormone therapy or surgery, and returns to identifying with his or her biological sex. A “desister” is someone who stops identifying as transgender even before taking medical steps.)

On this basis, the Position Statement directs paediatricians to centre the “adolescent’s expertise in their own life experience,” and proposes that doctors affirm a patient’s self-described gender identity and provide access to medical transition. The stated clinical role of the doctor is presumably not to engage in the etiology of gender distress in order to determine if transition is appropriate, but rather to facilitate the process of “support[ing] the adolescent in identifying and moving along the trajectory that best aligns with their individual goals.” This approach raises questions about clinical neutrality, diagnostic rigour, and safeguarding of informed decision-making.

The CPS’s endorsement of the treatments outlined in the Position Statement wrongly implies that the benefits of gender-affirming treatments in children and adolescents are known; that they clearly outweigh the risks; and that young people are able to weigh such explicitly described risks and benefits in order to give informed consent.

Here, we outline pertinent information that Canadian physicians need to know—including information about puberty blockers (PBs) and gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT)—that isn’t covered in the CPS Position Statement.

Evidence-Based and Rights-Based ModelsInternational treatment models for gender dysphoria in children and adolescents lie on a continuum from a rights-based approach to an evidence-based approach. The CPS Position Statement adopts a rights-based model, emphasising destigmatisation, depathologisation, patient autonomy, and support for the fulfilment of patient goals and self-determination. Under this rights-based model, a comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment prior to medical transition is often considered unnecessary.

The evidence-based approach, by contrast, emphasises patient safety and the effectiveness of offered treatments in promoting long-term improvements in health. While this approach also highly values patient autonomy, it is balanced by sound scientific research findings (i.e., evidence) and clinical expertise.

Before proceeding further, it is necessary to describe the principles of evidence-based medicine, which are applied in the material that follows. Under this framework, the best available data, ideally from systematic reviews of published studies, is used to assess the benefits and risks of interventions. This systematically considered evidence, along with patient values and preferences, is used to make treatment decisions.

Under the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) method, research evidence is evaluated according to factors such as risk of bias arising from methodological limitations, imprecision of estimates, indirectness of the evidence, inconsistency of results, and publication bias. The quality (sometimes called certainty) of evidence is rated as high, moderate, low, and very low based on these factors. Evidence from randomised controlled trials is initially rated high but may be rated down due to factors such as inadequate blinding or missing data. Evidence from observational studies is typically rated low but may be rated up based on large effect sizes, evidence of a dose-response relationship, or the use of methodologies that control for confounding.

With high quality evidence, further research is unlikely to change the degree of confidence in the estimates of effects from a treatment. With low quality evidence, further research is very likely to “have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.” And with very low quality evidence, “there is very little confidence in the effect estimate and the true effect may be substantially different.” Thus, with very low certainty evidence, there is no way to rule out whether the analysed intervention causes benefit or harm.

The Cass ReviewThe Cass Review was an independent evaluation of gender identity services for children and adolescents in the United Kingdom, commissioned by the NHS in response to concerns about clinical practices at the Tavistock Clinic’s Gender Identity Development Service.

The review, led by Hilary Cass, a former president of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2012–15) and Chair of the British Academy of Childhood Disability (2017–20), was the culmination of nearly four years of work consisting of commissioned research, consultations with clinicians and other allied professionals, meetings and focus groups with patients, their parents, and advocacy groups, and a review of international clinics. The final report included both a general discussion of paediatric gender medicine and specific service recommendations for NHS England.

Key findings and recommendations of the Cass Review included the following:

- The polarisation of transgender issues has created a challenging work environment, impeding the ability to consistently provide holistic care.

- Most clinical guidelines, including the Endocrine Society Guidelines, World Professional Association for Transgender Health Standards of Care Versions 7 and 8 (WPATH SOC-7 and SOC-8, respectively), and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) policy statement, are low quality and not recommended.

- Evidence for the benefit of social transition, puberty blockers, and cross-sex hormones is of low or very low certainty and quality.

- There is no evidence on long-term outcomes of children who receive “gender-affirming” care—which is to say, care focused on actively validating a patient’s declared “gender identity,” along with facilitating therapies aimed at aligning a patient’s body with that identity.

- A new treatment model was recommended, which includes comprehensive assessment and a focus on psychological support; medical transition is to provided only in a research setting, under rigorous medical oversight.

In a follow-up 2024 article, published after the Cass Review had been released, the authors of the CPS Position Statement (joined by three other co-authors) defended their affirmation-based approach by claiming that the Cass Review suffered from methodological flaws.

Specifically, they (incorrectly) stated that “many studies were excluded from the systematic reviews commissioned by the Review because they did not meet the ideal methodologic standard—randomized controlled trials, blinded studies, and multi-institutional research.”

In fact, the systematic reviews in question considered 103 non-randomised observational studies; and employed the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, a tool designed to assess the methodological quality of such data. Only two of these observational studies were rated high quality. In all, 58 percent were deemed to be of sufficient quality to be included in the Cass Review’s synthesis.

In their 2024 article defending the CPS Position Statement, Drs Vandermorris and Metzger pointed to critiques of the Cass Review co-authored, respectively, by Yale School of Medicine Professor Meredithe McNamara, and University of Galway Psychology Lecturer Chris Noone. However, a published response in the medical journal Archives of Disease in Childhood, co-authored by Evelina London Children’s Hospital paediatrician C. Ronny Cheung, argued that these two anti-Cass critiques had misrepresented the role and process of the Cass Review, and that the methodologies applied by the critics were themselves unfounded.

A central criticism raised by both anti-Cass commentaries was that the Review had been led by a single individual with no experience in gender-affirming care. However, Cheung and his co-authors noted that British independent reviews of this type are typically conducted by “a respected public figure with no ties to the area under review.” Such independence is intended to minimise bias.

In a peer-reviewed article entitled, Paediatric gender medicine: Longitudinal studies have not consistently shown improvement in depression or suicidality, Kathleen McDeavitt of the Menninger Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Baylor College of Medicine fact-checked various critiques of the Cass Review. She found that they “made claims which were inaccurate, or which lacked essential clarification/contextualization.”

Australian psychiatrist and medical historian Alison Clayton and her co-authors also responded to criticisms of the Cass Review; and in that publication discussed its application to Clayton’s own country, which has implemented “affirmation” policies and practices similar to those in Canada. And Dr Cass herself co-authored a separate published article responding to common criticisms of her report. We do not reproduce all of these responses, other than to note here that others have quite adequately defended the Cass Review’s methodology.

Cass found that the evidence base for gender-affirming care for youth is ‘remarkably weak,’ and questioned the quality and credibility of the WPATH SOC and ESG positions—which the Canadian Paediatric Socity had explicitly relied on.

Drs Vandermorris and Metzger have continued to insist that “the approach to gender-affirming care for adolescents in Canada remains grounded in the tripartite approach to evidence-based practice… available evidence, clinical expertise, and patient and family goals and values… and remains unaltered by the publication of the Cass Review.” However, it is unclear how this proposition can be defended.

Evidence-based guidelines must be grounded in systematic review of all available evidence. The Cass Review found that the evidence base for gender-affirming care for youth is “remarkably weak,” and brought into question the quality and credibility of the WPATH, SOC, and ESG positions—which the CPS Position Statement had explicitly relied on.

The Cass Review also highlighted how the treatment results of a narrowly defined group of children had become adopted and applied more generally to all young people experiencing gender distress, leading some clinicians to abandon prudent, conventional clinical practice. It also highlighted the lack of consensus among clinicians treating this population, the precipitous rise of gender dysphoria, and the emerging literature on detransition.

The findings of the Cass Review highlight many shortcomings of the CPS Position Statement—including, that

- it is based on clinical guidelines that the Cass Review found to be unreliable;

- it incorrectly casts gender identity as a stable characteristic, and, in so doing, ignores the history of the development of gender distress in young people, and the interconnection between gender-related distress and comorbid mental health conditions;

- it provides no discussion of the precipitous rise of transgender identification among young people—particularly adolescent girls, most with mental health comorbidities and/or neurodevelopmental conditions;

- it provides no discussion of the growing literature on regret or detransitioners, and how the experiences of detransitioners could inform clinical practice;

- it overstates the benefits, and understates the risks, of puberty blockers and gender-affirming hormone therapy; and

- it ignores the complex issues of obtaining genuine informed consent for gender-affirming treatments.

Each of these points will be discussed below.

Unreliable GuidelinesThe Cass Review commissioned two systematic analyses of all policy documents published between 1998 and 2022 that serve as clinical guidelines for children and young people experiencing gender dysphoria. The analyses applied an internationally accepted tool, Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE II), to assess the quality and rigour of guideline development and the reliability of treatment recommendations.

All in all, Cass found that “most clinical guidance lacks an evidence-based approach and provides limited information about how recommendations were developed.”

The appraised guidelines included SOC-7 and SOC-8, the 2018 AAP statement on gender-affirming care, the Endocrine Society Guidelines (ESG) for the Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons, guidelines promulgated by the Council for Choices in Healthcare in Finland, Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare guidelines, along with eighteen other similarly-themed documents. All in all, it was found that “most clinical guidance lacks an evidence-based approach and provides limited information about how recommendations were developed.”

WPATH SOC-8, the most widely cited and most influential of the above-referenced guidelines, scored amongst the lowest for developmental rigour and editorial independence. Except for the Swedish and Finnish guidelines, which followed rigorous practices, all other guidelines contained high degrees of circular referencing. Rather than conducting independent reviews of evidence, most guidelines relied on the WPATH and ESG policies.

And as Cass noted, even these two documents do not stand as independent authorities. The pair “are closely interlinked,” she noted, “with WPATH adopting Endocrine Society recommendations, and acting as a co-sponsor and providing input to drafts of the Endocrine Society guideline.”

The CPS Position Statement was not included in Dr Cass’s commissioned systematic review, as it was published after the 31 December 2022 deadline. But as noted above, it too relied heavily on the ESG, the AAP policy statement, and WPATH SOC-8—all of which were found to have been drafted without rigorous, transparent guideline-development practices.

WPATH SOC-8 was also criticised for failing to use the systematic reviews that WPATH itself had commissioned—three of which were of gender-affirming care in adolescents. These found only low-certainty evidence that hormone therapy was associated with improved measures of psychological well-being and quality of life. Even so, WPATH adopted strong recommendations for hormone therapy that “overstat[ed] the strength of the evidence.”

As McMaster University Health Research Methods expert Gordon Guyatt has noted, “systematic reviews are meant to ensure that doctors’ recommendations are based on objective evidence, not ‘habit or misguided expert advice.’” WPATH’s lack of reliance on systematic reviews, coupled with the unwarranted strength of its recommendations, indicates that SOC-8 and any guidelines based on it cannot be considered evidence-based documents.

Since the publication of the Cass Review, further evidence has emerged indicating that WPATH disregarded the principles of evidence-based guideline development. When a court in the United States ordered WPATH to disclose all of the documents relating to the creation of SOC-8, it was found that SOC-8 initially included recommended minimum ages for hormonal treatments and surgeries; however, shortly after publication, a correction was issued, removing all age recommendations, except for a minimum age of eighteen for phalloplasty. Although WPATH did not provide any explanation for the change, the disclosed documents revealed that the change resulted from political pressure applied by the United States Department of Health and the AAP—rather than having been made on the basis of scientific evidence or even expert consensus.

Disclosed documents have since revealed that WPATH had commissioned a series of systematic reviews from Johns Hopkins University regarding thirteen review questions to inform the development of SOC-8, but then only published two of these reviews. Internal emails revealed that WPATH had restricted the ability of the Johns Hopkins researchers to publish the results of these systematic reviews; and, after the first review was published, insisted on an approval process that gave WPATH veto power over the contents of the reviews.

Incorrectly Casting Gender Identity as a Stable CharacteristicThe CPS Position Statement acknowledges, in passing, that “emerging theoretical and empirical studies that employ multidimensional and dynamic constructs of gender may afford more nuanced insights into this domain, throughout [a patient’s life course].” Yet the authors ultimately disregard such perspectives, as well as the associated empirical evidence, and instead choose to endorse an affirmation model based entirely on a young person’s asserted understanding of his or her gender identity.

The underlying assumption of the affirmation model, espoused by SOC-8 and endorsed by the CPS, is that gender identity is stable—or at least stable enough to warrant interventions that can result in permanent medical effects. This assumption has been brought into question by the growing number of desisters and detransitioners, and by the recent rapid increase in the number of young people presenting with gender distress.

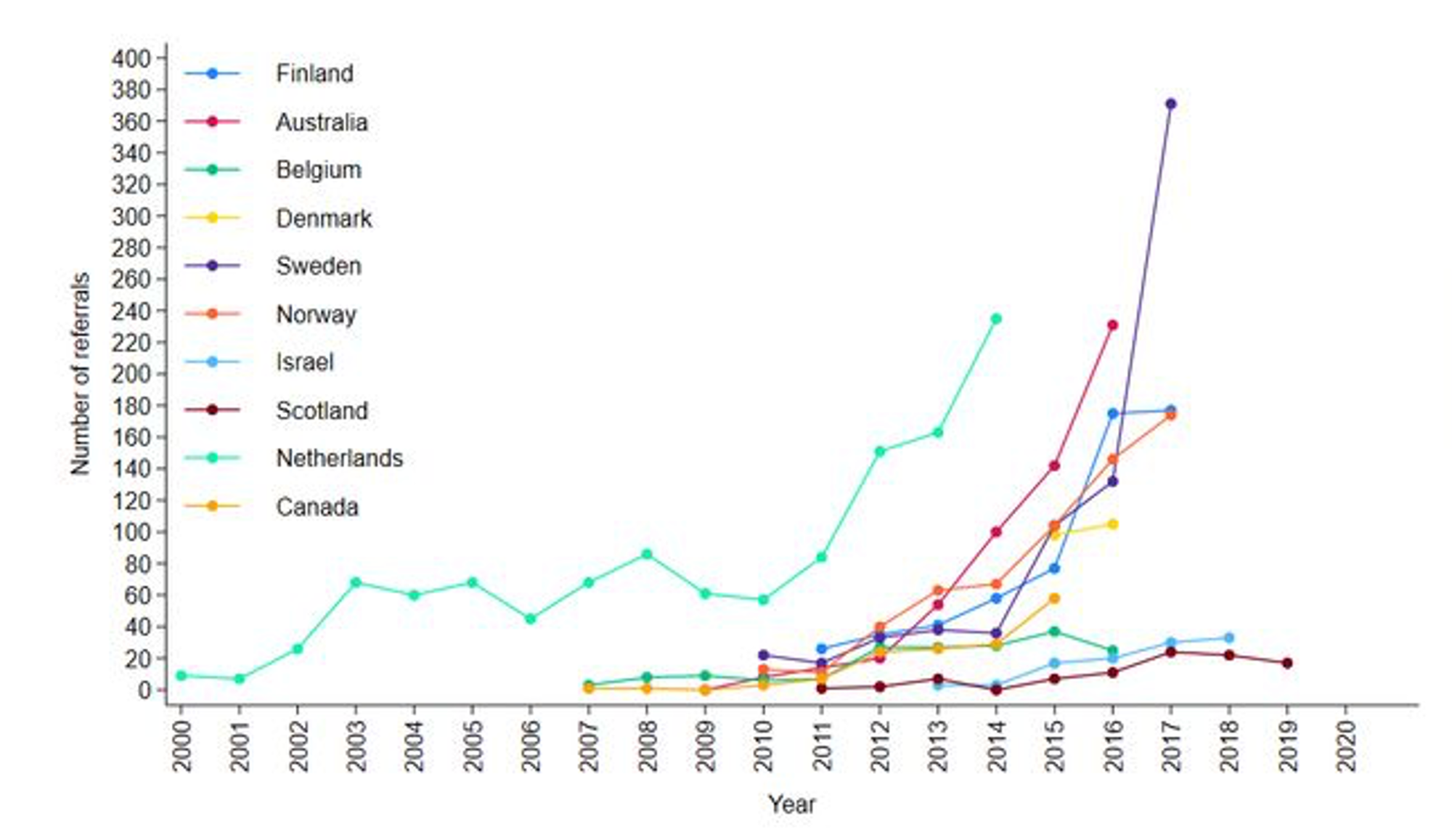

Historically, gender dysphoria emerging post-puberty was rare, as the condition generally presented in young children (with a significantly higher prevalence in natal males). Beginning in the early 2000s, however, the number of referrals to gender clinics began to increase, with a precipitous rise beginning in 2014 and a newly skewed sex ratio favouring natal females at ratios ranging from 2:1 to 3:1.

The figure reproduced below indicates that this pattern has been observed across the Western world, including in Canada. Moreover, these young people tend to present with comorbid mental health and neurodevelopmental conditions, or a history of trauma, with prevalence rates significantly higher than those observed in the general population of children and adolescents.

The Cass Review noted that “there is broad agreement that gender incongruence, like many other human characteristics, arises from a combination of biological, psychological, social and cultural factors”; and that while greater societal acceptance of trans identities may partially explain the rise of gender-clinic referrals, it is unlikely to explain it entirely.

Acceptance cannot explain the above-noted sex-ratio reversal; nor why those with mental health and neurodevelopmental conditions are over-represented among the trans-identified population. The dramatic trend depicted in the figure above highlights further issues, such as whether mental comorbidities are causal or consequential, as well as the impact of social influences (peer and online) and other stressors.

The gender-affirming model endorsed by the CPA fails to explicitly consider how all these factors may contribute to gender experience and distress—as the underlying assumption of the affirmation model is that the phenomenon is explained by a mismatch between one’s sex and one’s asserted gender identity.

Persistence and DesistenceThe CPS Position Statement ignores research that has found that gender-related distress or incongruence in children often resolves during puberty or early adulthood; with many individuals later identifying as gay or lesbian.

Some gender-affirming clinicians have posited that childhood gender dysphoria that continues during puberty will persist into adulthood. As a 2024 letter published in the Archives of Sexual Behavior has noted, however, the rate of persistence into adulthood remains unknown.

The claim that persistence of gender distress into adolescence is predictive of life-long gender dysphoria is also challenged by detransitioners, who typically experienced dysphoria through adolescence before it resolved in adulthood.

Most studies of gender dysphoria in children were conducted at a time when social transition was discouraged. In a more recent study of children who had socially transitioned, more than ninety percent continued to identify as transgender five years later. Thus, the high rate of desistance shown in numerous earlier studies may be a reflection of the stigma at the time; or, as is perhaps more likely, to quote the Cass Review: “it is possible that social transition in childhood may change the trajectory of gender identity development for children with early gender incongruence.”

This latter concern has been raised by others, and was raised in the early Dutch literature on dysphoria. We have little data regarding the new cohort whose gender dysphoria first presented post-puberty; but the few studies of detransitioners indicated that an approach that allows for more open-ended exploration and reflection, rather than affirmation, might better allow all individuals to make more informed decisions.

Regret and DetransitionThe CPS Position Statement overlooked regret and detransition. The rate of detransition among young people is unknown, especially in regard to recently observed adolescent-onset cases. Studies define detransition in multiple ways, leading to widely differing estimates. Studies reporting low detransition rates typically suffer from multiple limitations, such as short follow-up periods, high loss to follow-up, highly restrictive definitions, and biased samples. Gender-clinic data are likely to underestimate detransition rates, as detransitioners are often reluctant to return to clinics that facilitated their medical transition due to fear of judgment or dismissal, and concerns of stigma.

A recent study of participants referred to a Finnish adult gender clinic for detransition over a two-year window reported that the number of detransitioners appeared to be growing, and that the time to detransition may be decreasing. All the natal female detransitioners experienced major regret (e.g., dysphoria due to their new appearance, or an expressed desire for detransition surgery). None of the detransitioners reported external reasons, such as discrimination, for detransitioning.

The CPS Position Statement recommended a biopsychosocial assessment prior to commencement of puberty blockers or gender-affirming hormone therapy; but failed to specify the purpose of such an assessment, what such an assessment must entail, which clinical discipline is best suited to conduct it, or how a comprehensive assessment seeking to uncover factors contributing to gender distress is consistent with a “gender-affirming” model.

It’s worth noting that the more cautious “developmental, biopsychosocial model” developed by sexologist Kenneth J. Zucker—which involves clinical interviews with youth and their families, psychological testing, and input from parents and teachers to develop a multifactorial case formulation that accounts for co-occurring conditions and avoids premature closure—shares key features with the approach recommended by the Cass Review. Cass calls for a holistic evaluation of biological, psychological, and social contributors to gender-related distress, conducted by a multidisciplinary team with careful screening for neurodevelopmental and mental health conditions to ensure individualised care.

Despite their clinical rigour, such approaches have been criticised as non-affirming, and even framed as “gatekeeping” and “conversion therapy” due to their departure from an affirming approach.

Furthermore, legislation ostensibly targeting “conversion therapy” can hinder clinicians from offering comprehensive care to gender-distressed youth. While psychotherapy—aimed at fostering self-understanding and informed decision-making—is distinct from discredited efforts to change a patient’s sexual orientation, the legal boundaries remain unclear. In many jurisdictions, including Canada, there are exemptions to anti-conversion-therapy laws that permit therapeutic exploration. But the vague scope of the applicable prohibitions and protections leaves clinicians uncertain whether anything short of automatic affirmation qualifies as conversion therapy. The CPS Position Statement’s unequivocal endorsement of affirmation may further discourage thorough psychotherapeutic assessments.

The Cass Review highlighted similar concerns in the UK, where clinicians feared that standard therapeutic approaches could be misclassified as conversion practices, and so Dr Cass recommended safeguards in legislation to protect clinical judgment. The Cass Review’s call for holistic, individualised care—including screening for neurodevelopmental and mental health conditions—has since been adopted by NHS England.

The CPS Position Statement noted that “transgender or gender-diverse youth are at elevated risk for adverse health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, eating disorders, self-harm, and suicide.” It further asserted that these conditions can be explained “in part” by the social stigma associated with gender nonconformity, or by minority stress (stress imposed by societal prejudice and discrimination). It failed to consider that gender dysphoria, as pointed out in the Cass Review, may be secondary to these mental health conditions, and/or to traumatic events preceding the onset of gender dysphoria.

Moreover, the CPS Position Statement did not address the elevated rates of neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism spectrum disorders and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder frequently associated with gender distress—which cannot be explained by minority stress.

In studies of detransitioners, many reported that their gender dysphoria and subsequent transgender identity resulted from other factors such as mental health issues, neurodiversity, trauma, difficulty accepting their sexuality, or misogyny—or of their having confused sexuality with transgender identity. The majority of detransitioners in one study reported they felt they were inadequately assessed before being approved for transition.

A recent study of detransitioners reported that although patients accurately presented their mental health challenges, and were often diagnosed with multiple psychiatric conditions, they were nonetheless cleared for gender transition—thereby highlighting how a focus on affirmation and centring a young person’s requests may hinder holistic care and result in diagnostic overshadowing (i.e., attributing the debilitating effects of the underlying mental-health conditions to gender dysphoria).

Although gender-distressed young patients frequently present with mental health comorbidities, primary care providers typically do not conduct holistic assessments or treat these conditions, opting instead to refer patients to gender clinics. Unfortunately, those gender clinics typically only assess readiness for puberty blockers and gender-affirming hormone therapy, and do not provide therapeutic open-ended exploration of the causes of the gender distress.

A journalistic investigation in Quebec found that a fourteen-year-old girl could get a prescription for testosterone at a private clinic in just ten minutes.

Data from ten hospital gender clinics across Canada showed only 45.6 percent of patients had been seen by a psychologist or psychiatrist (though it is unclear for how long and whether an exploratory or affirmative approach was used) before their clinic visits; yet 62.4 percent received puberty blockers on their first visit. A journalistic investigation in Quebec found that a fourteen-year-old girl could get a prescription for testosterone at a private clinic in just ten minutes.

Research also has highlighted detransitioner reports that gender clinic staff had been overly enthusiastic in supporting medical transition, or had even tried to convince patients that they were transgender. Although detransitioner accounts of such experiences present current perspectives of past events, and memories are not always reliable, it is prudent to consider these narratives.

Puberty BlockersThe use of puberty blockers for gender dysphoria was originally based on two Dutch studies of a cohort of carefully selected patients who first experienced gender distress in early childhood. The treatment regime, known as the “Dutch Protocol,” consisted of puberty blockers at the age of twelve, gender-affirming hormones at age sixteen, and surgeries at age eighteen. Before beginning puberty suppression, all participants were extensively evaluated by an interdisciplinary team to ensure participants’ psychosocial functioning was adequate, and to rule out any serious psychiatric comorbidities. All patients received psychological support in addition to medical transition and had the support of parents.

These studies have faced significant criticism for their methodological shortcomings. Although the research began with 196 patients, only 70 were reported in the first study, and 55 in the second, with complete data being collected for only 40—resulting in critical attrition bias. Notably, the final group excluded three patients who developed diabetes/morbid obesity; and one who died due to post-gender-affirming-surgical necrotising fasciitis. Key limitations included the absence of a control group, and a lack of physical health outcomes assessments.

Despite these flaws, the protocol was rapidly extended to a broader population: adolescents whose gender distress emerged during or post puberty, and individuals with unmanaged comorbid mental health conditions. Increasingly, parental concerns have come to be dismissed as misinformed. Indeed, many clinicians now regard involvement of parents as unnecessary.

The CPS Position Statement asserted that puberty blockers “provide a young person with time to further explore their gender identity,” a claim rooted in the Dutch research. The Cass Review questioned this assumption, noting that “the vast majority of those who start puberty suppression continue to masculinising/feminising hormones.” Multiple studies report continuation rates to subsequent hormone therapy exceeding 95 percent—suggesting either near-perfect predictive accuracy, or that the treatment itself may influence identity development. Such precision is not achievable in clinical practice. If puberty blockers were truly neutral in their effect, much greater variability in outcomes would be expected.

Dr Cass hypothesised that early intervention may prematurely alter the natural trajectory of identity formation. As Dr Cass wrote, “young people [may] have to understand their identity and sexuality based only on their discomfort about puberty and a sense of their gender identity developed at an early stage of the pubertal process.”

Furthermore, since sex hormones are integral to brain development, particularly during critical periods such as puberty, it has been hypothesised that puberty blockers may impair a young person’s ability to assess the subsequent decision to begin gender-affirming hormone therapy when that time arises.

The CPS Position Statement asserted that puberty blockers are reversible, implying their use has limited risk—which is not supported by evidence either. While puberty blockers used for precocious puberty allow normal development to resume when discontinued at the appropriate time, this cannot be extrapolated to the initiation of puberty blockers during the normal window of puberty.

Early Dutch research raised questions regarding suppressing puberty during the normal period of development, including with respect to bone density, body composition, and cognitive development; and significant gaps in knowledge still remain regarding how long puberty blockers may be used safely, as well as how long-term use may affect neurocognitive development. Framing puberty blockers as simply reversible oversimplifies their impact and reflects an atomistic (non-holistic) view of adolescent development.

None of the seven relevant citations in the CPS Position Statement supported the assertion that puberty blockers are reversible when used during the normal window for puberty:

- The first citation was WPATH SOC-8, which in turn cited a case report of two adolescents—one of whom was untreated due to insurance denial, while the other progressed to cross-sex hormones.

- The second cited the ESG, which in turn cited articles on puberty blockers used to treat central precocious puberty, as well as two articles on men with gonadotropin deficiency—contexts that are unrelated to typical adolescent development.

- The third reference provided no data on reversibility, as all patients in this study either proceeded to cross-sex hormones or were lost to follow up.

- The remaining citations were commentaries on a 2011 Dutch study and contained no new evidence.

Puberty is a critical developmental window involving multiple interrelated physical, cognitive, and social changes. Hormone suppression during this period has risks that have been recognised but not adequately studied. The CPS Position Statement briefly acknowledged some of these risks but offers limited discussion. For instance, most peak bone mass, an important predictor of osteoporosis risk, is gained during puberty. Administration of puberty blockers disrupts this process by slowing the accrual of bone mineral density (BMD) at a time when it should be increasing rapidly.

While the CPS Position Statement noted that partial recovery may occur with gender-affirming hormone therapy, the findings in this area are mixed. Studies suggest that transboys (natal females) who have proceeded to long-term testosterone therapy may regain bone mineral density; but transgirls (natal males) showed persistent deficits with long-term oestrogen therapy. Other studies have found that bone mineral density remained below pre-treatment levels despite hormone therapy. Recent research indicates puberty blockers reduce bone mineral density, and that subsequent cross-sex hormone treatments fail to compensate for this loss of bone density. No studies are known to have examined how the duration of puberty blockers impacts bone health, underscoring the need for further research.

The CPS Position Statement discounted concerns regarding the effects of puberty blockers on cognitive development, stating that such concerns “have not been substantiated.” While this may be technically true, as the field of paediatric gender medicine is relatively new, it is well established that puberty is a critical period for brain development, with sex hormones playing a significant role. Disrupting the actions of hormones during puberty may therefore affect cognitive development. This is supported by studies on both non-human animals and humans. (While a 2022 study may give the impression that puberty blockers do not negatively impact cognitive development, the methodological design precludes definitive conclusions.) Ultimately, the long-term effects remain unknown, and further research is needed to assess the cognitive impacts of puberty blockers.

The long-term effects of puberty suppression during normally timed puberty on adult sexual function also remain unknown. In natal males, early use of puberty blockers has often resulted in an underdeveloped penis, with insufficient tissue to achieve satisfactory depth in a penile inversion vaginoplasty; thereby requiring the use of intestinal tissue—a more complex and risky procedure. Marci Bowers, a former president of WPATH and a co-author of SOC-8, has publicly stated that she is not aware of any patients who began puberty blockers at Tanner Stage 2 who were able to achieve orgasm after vaginoplasty.

Since most studies of sexual function in transgender people have been of patients who transitioned as adults, little is known about the impact of puberty suppression on orgasmic capacity. A retrospective cohort study of 37 transfeminine individuals who received puberty blockers between Tanner stages 2 and 5, and vaginoplasty at a mean age of 20.9 years, found that 67 percent of sexually active participants regularly experienced one or more sexual difficulties, such as lack of sexual desire, lack of arousal, difficulty in reaching orgasm, premature orgasm, and pain during intercourse. A more rigorous discussion of these studies, their limitations, and their interpretive risks is needed.

Fertility outcomes differ significantly depending on the treatment path. Research has found that the fertility of children treated with puberty blockers for precocious puberty was not affected once normal puberty resumed. But it is not clear that this is the case if puberty is blocked during the normal time window. In any event, those who begin puberty blockers in early puberty and proceed to gender-affirming hormone therapy are likely to be sterile, since puberty blockers halt the germ cell maturation required for viable gametes. A histology study of orchiectomy specimens found no mature sperm in patients whose puberty had been blocked at Tanner Stages 2 or 3.

On the other hand, delaying initiation of puberty blockers to allow for egg or sperm cryopreservation would mean undergoing many of the physical changes associated with puberty that puberty blockers are intended to prevent—and, as a result, patients seldom choose this option. Fertility preservation prior to gamete maturity remains experimental in males, and in females, reproductive success is very limited.

The systematic review of puberty blockers commissioned by the Cass Review could not draw any reliable conclusions regarding the effect of puberty blockers on gender-related outcomes, psychological and psychosocial health, cognitive development, or fertility. It found that bone health and height might be compromised. These findings have been confirmed by a more recent systematic review led by methodologists from McMaster University.

Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy (GAHT)The CPS Position Statement indicates that “GAHT is considered safe for adolescents, but it can have associated short- and long-term health risks” that “are beyond the scope of this statement.” These risks are important for paediatricians and primary care providers to understand so they can determine if gender-affirming hormone therapy is appropriate, ensure informed consent, and monitor ongoing health risks.

Gender-affirming hormone therapy is often a lifelong commitment. The only study that followed patients from puberty blockers through gender-affirming hormone therapy to adulthood is the original Dutch cohort study, which did not examine the impact of treatment on physical health. More recent studies of adults who have received GAHT have found serious health risks.

Tracking of adverse drug reactions from gender-affirming hormone therapy is complicated by the fact that these medications are prescribed to transgender people off-label (which is to say, for a purpose or patient population that was not officially approved by applicable regulatory bodies); and the risks listed by the drug manufacturer relate to people whose sex is the opposite to that of a transgender patient. Despite the fact that the impacts of gender-affirming hormone therapy are likely cumulative (and so may take years to manifest) and the lack of long-term follow up studies, a growing number of case reports and studies have found associations between GAHT and various morbidities including granulosa cell tumours, invasive breast cancer, thyroid cancer, pelvic floor dysfunction, and idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

Various systematic reviews and literature reviews have found that the evidence that gender-affirming hormone therapy leads to improvements in mental health or reductions in suicidality was of low or very low certainty—and that the observed effect sizes were small with potentially little clinical significance.

A systematic review on gender-affirming hormone therapy commissioned by Dr Cass found “limited evidence regarding gender dysphoria, body satisfaction, psychosocial and cognitive outcomes, and fertility.” While some studies showed improvements in psychological outcome at a twelve-month follow up, these findings were confounded by concurrent psychological support and psychotropic medications, and therefore provided only low certainty evidence.

Results for height/growth, bone health, and cardiometabolic effects were inconsistent. Since most studies were of adolescents who had also received puberty blockers, the independent effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy generally remain unclear.

One 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis, however, did find strong evidence that transgender people were at higher risk of cardiovascular disease compared to non-transgender people of the same birth sex—including increased risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, and venous thromboembolism. These findings were confirmed by another recent systematic review of gender-affirming hormone therapy for those under the age of 26, which found high certainty evidence for cardiovascular events in transmen treated with testosterone and very low certainty evidence for improvement in gender dysphoria, global function, and depression.

A recent systematic review of gender-affirming hormone therapy on patient-reported outcomes in Canada highlighted the “need to improve standardization of outcome measurement for gender-affirming hormone treatments in order to improve the robustness of the evidence base, thereby contributing to higher quality research and evidence-informed clinical practice.”

The Cass Review found that the evidence base for psychological benefit from hormones was weak. While the option to provide hormones from age sixteen remains available in England, the Cass Review recommended “an extremely cautious clinical approach” and the requirement that “every case considered for medical treatment be discussed [by] a national Multi-Disciplinary Team.”

Informed ConsentThe CPS Position Statement did not discuss informed consent. Under Canadian law (except in Quebec, which has a minimum consent age of fourteen), there is no minimum age for medical consent. Instead, physicians must assess a minor’s capacity on a case-by-case basis to determine whether a child understands the nature and consequences of the proposed treatments. As noted above, WPATH SOC8, which the CPS relied on, specified no age restrictions for political reasons, except for a recommended minimum age of eighteen for phalloplasty.

Concerns about individual young people’s capability to provide informed consent for gender-affirming therapies are grounded in both developmental science and ethical analysis. It is well documented that the prefrontal cortex, integral for rational decision-making and impulse control (i.e., executive functions), is among the last parts of the brain to mature, leaving adolescence a period of heightened vulnerability to high risk-taking and social pressure. It is also generally understood that identity continues to develop and evolve into adulthood, and that adolescence is a crucial stage of identity exploration and development.

As such, gender-affirming care presents a complex ethical landscape. Young people are required to make decisions about treatments that have a high degree of uncertainty and potential life-long consequences on fertility, sexual function, bone density, and general health, as well as on social life and intimate relationships—at an age when their identity and cognitive decision-making capacity have not fully developed.

Informed consent requires that the patient have capacity to consent, understand the nature and consequences of the treatment and any alternative treatments (including no treatment), and be free of coercion. Researchers have noted that adolescents’ ability to think abstractly and foresee the consequences of treatment choices can be limited, underscoring the moral dilemma that arises when there are doubts about an adolescent’s ability to comprehend the lifelong implications of gender-affirming medical treatments.

During a WPATH panel discussion, Dr Metzger, a co-author of the CPS Position Statement, acknowledged that fourteen-year-olds are unable to understand the impact of loss of fertility, and that discussing fertility preservation was like talking to a “blank wall.” This obviously calls into question whether these young people have sufficient understanding of the long-term effects of puberty blockers and gender-affirming hormone therapy to provide informed consent.

Patients should be made aware of the evidence that gender dysphoria can resolve without treatment, and the low certainty of the evidence that gender-affirming treatments are beneficial. Moreover, while informed consent is often dealt with as a staged process, with the child patient and/or parents being asked for consent separately at each step, in practice the distinction between the stages is often blurred. Starting puberty blockers is associated with a greatly increased probability of proceeding to gender-affirming hormone therapy, which, in turn, leads to increased probability of surgeries. Fully informed consent requires that the patient understand the ramifications of the entire gender-transition process before commencing the first step.

An affirming approach, by its nature, may discourage exploration of underlying causes of gender distress, thereby potentially limiting critical insights and compromising patient autonomy.

Patient and family goals, values, and preferences are shaped by the information they receive. In Canada, it is unclear whether patients consistently receive balanced comprehensive information about gender-affirming care. Without a full understanding of the medical concepts, risks, benefits, and alternatives, preferences may be misinformed. Moreover, an affirming approach, by its nature, may discourage exploration of underlying causes of gender distress, thereby potentially limiting critical insights and compromising patient autonomy.

While informed consent is essential to uphold patient autonomy, informed consent alone does not determine the ethical appropriateness of a treatment. Physicians must also consider and weigh the ethical principles of beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice. Ethical practice requires evidence that a proposed intervention offers a potentially positive benefit–harm ratio before consent is relevant. Currently, this is not the case with gender-affirming medical treatments. Autonomy does not supersede all other bioethical principles, but must be balanced against the physician’s duty to safeguard the patient’s best interests and right to an open future. There remains great uncertainty in paediatric gender medicine regarding diagnostic reliability and scientific evidence. Autonomy alone, in such cases, cannot ethically justify a treatment that may potentially compromise long-term welfare.

Final ThoughtsPhysicians must consider and weigh the ethical principles, not solely of autonomy, but also of beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice. Ethical practice requires evidence that a proposed intervention offers a potentially positive benefit–harm ratio before consent is relevant. And yet this is currently not the case with gender-affirming medical treatments. As others have rightly pointed out, prioritising patient autonomy over patient welfare is a departure from well-established bioethical norms. Autonomy should not supersede all other bioethical principles; but must be balanced against the physician’s duty to safeguard the patient’s best interests and right to an open future.

The rights-based affirmation approach for the treatment of gender dysphoria promoted by the CPS Position Statement is becoming obsolete. It is being replaced globally by an evidence-based approach prioritising non-maleficence and beneficence; and a neutral psychological exploration rather than immediate affirmation. Countries adopting an evidence-based approach include Finland, Sweden, Norway, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Italy, and the United States, where the American Society of Plastic Surgeons just announced there is “insufficient evidence” that the benefits of performing “affirming” surgeries on gender dysphoric minors outweigh the attendant risks.

The rights-based affirmation approach for the treatment of gender dysphoria promoted by the CPS is becoming obsolete. It is being replaced globally by an evidence-based approach

Recent developments in psychotherapeutic practice further underscore a shift in the care of gender-distressed youth. Other jurisdictions are adopting practices grounded in the Cass Review’s recommendations, emphasising holistic assessment, individualised formulation, and developmentally appropriate care, which reconnects the field with the practice of child and adolescent mental health, thereby rejecting the exceptionalisation of gender dysphoria that has occurred in recent years.

It is notable that the CPS continues to uncritically promote the gender-affirming model despite (a) generally calling for major reforms to improve the safety and efficacy of medications prescribed to Canadian children; and (b) acknowledging that Canada can learn from the European Union regarding paediatric medicine and research.

The CPS’s outdated approach is reflected in a recent paper published in Paediatrics and Child Health, which provides case presentations and “learning points” for general paediatricians on how to treat gender-distressed youth. The article refers readers to the CPS Position Statement and resources created by various Canadian gender clinics and groups focused on a rights-based model. Unfortunately, it does not mention the Cass Review, any systematic reviews of the evidence, the debate on how best to care for these youth, or any international developments.

Canadian gender-distressed youth deserve the same standard of care as that provided in jurisdictions that have kept up to date with evolving best practices. As the Editor-in-Chief of the British Medical Journal recently pointed out, “the Cass review is an opportunity to pause, recalibrate, and place evidence-informed care at the heart of gender medicine. It is an opportunity not to be missed for the sake of the health of children and young people.”