The current wave of mass demonstrations and unrest sweeping across Iran have been met with brutal crackdowns by the Islamic Republic’s police forces and paramilitary groups. Yet even as Iranians plead for foreign intervention, particularly from the United States, President Trump’s assurances that “help is on its way” remain empty rhetoric. While he congratulates Tehran for allegedly suspending hundreds of executions and public hangings, like his predecessors, Trump underestimates the suicidal fanaticism on which the Islamic Republic is built.

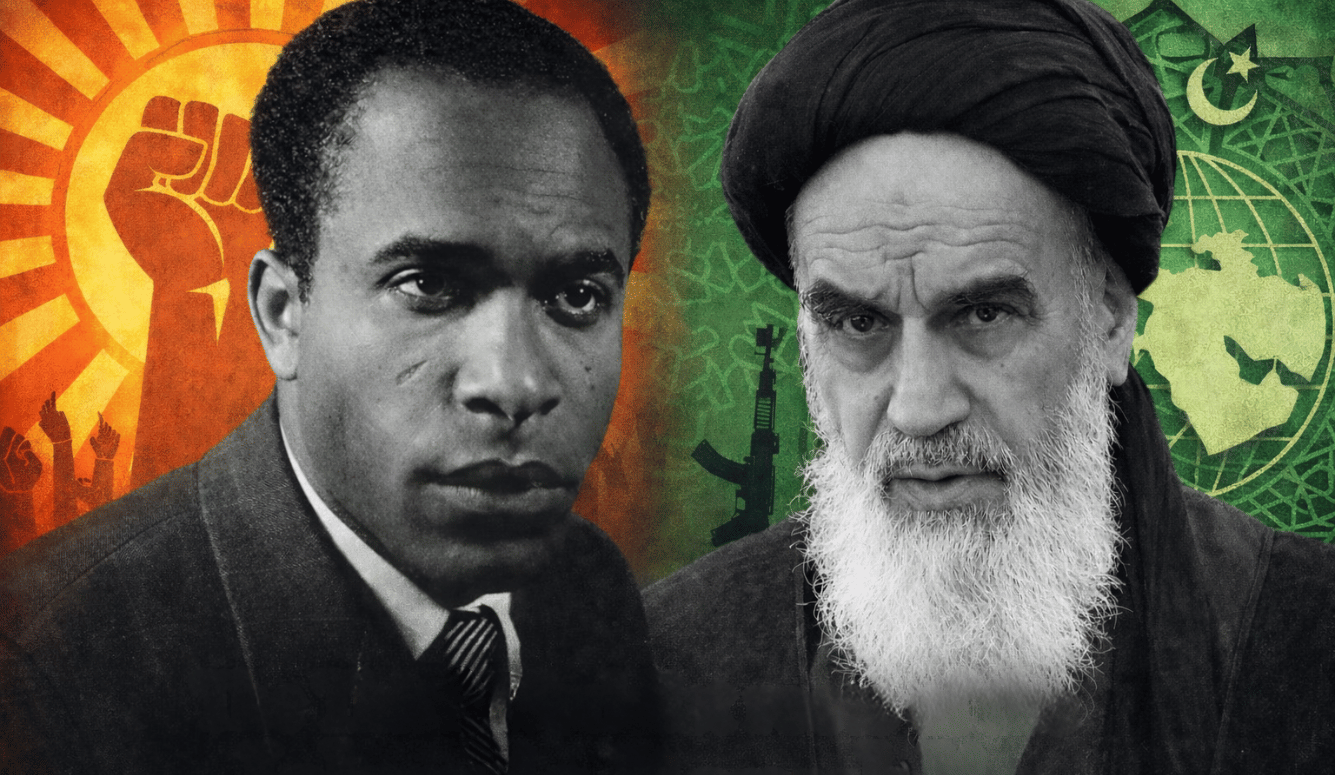

For decades, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has presented himself as a critic of Western colonialism. This posture, however, is hardly new. In his 1970 lectures in Najaf, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini railed against the “imperialist government of Britain,” dismissed constitutionalist movements as tools of foreign powers, and urged followers to conceal their true aims from those he claimed had “sold themselves to imperialism.” In a March 1980 radio address, he declared that Iranians must resist the “devourers led by America, Israel, and Zionism,” insisting that no foreign presence on Iranian soil would be tolerated and urging his followers to “export our revolution to the world.” In this, both Ayatollahs were parroting language and cynically hijacking an ideology most prominently articulated by Frantz Fanon.

In his 1961 book Les Damnés de la Terre (The Wretched of the Earth), Fanon declares that “decolonisation is always a violent phenomenon.” Violence against the coloniser, he insists, is purifying, redemptive, and world-creating. It is a formulation whose resonance is starkly apparent in slogans like “Globalise the Intifada.” “The colonised man is one tormented,” writes Fanon, “who dreams every day of becoming the tormentor.” This is the kind of explanation that has led some to justify Hamas’s actions on 7 October.

Les Damnés de la Terre argues that violence is the only path to self-actualisation or, as Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1961 preface puts it, the sole cure for “colonial neurosis,” a pathology that supposedly renders its perpetrators incapable of moral agency and therefore exempt from moral responsibility. Therein lies the fundamental premise of Third-Worldism. “The Third World discovers and articulates itself in this manner,” according to Sartre—and only in this manner.

During the mid-1960s, Fanon’s work was translated into Persian by Abolhasan Banisadr, who served as Iran’s first president from January 1980 until his break with Khomeini led to his abrupt ousting in June 1981. Banisadr’s translation of Les Damnés de la Terre, published in 1966 under the title Duzakhiyān rūye zamīn, was circulated by Jalal Al-e Ahmad, the intellectual mentor for a generation of Shi’a ulama (clerics), including Khomeini and the young Khamenei.

Born in Tehran in 1923 to a devout but impoverished Shi’a family, Al-e Ahmad initially pursued religious study in Najaf before abandoning clerical life. Returning to Iran in the mid-1940s, he gravitated toward the Marxist Tudeh Party, only to break with it after recognising its subservience to Moscow. By the mid-1950s, Al-e Ahmad’s successive disappointments with anti-clerical socialist movements had driven him back to Islam, which he saw as the only viable foundation for a national Iranian identity. It is at this point that Al-e Ahmad began to formulate the Third-Worldist Islamism later adopted by the architects of the Islamic Republic.

Al-e Ahmad, who spoke fluent French, had almost certainly encountered Fanon’s works in the original long before Banisadr’s translations became available in Iran. In 1962, one year after the appearance of Fanon’s treatise on decolonisation, Al-e Ahmad published Gharbzadegi. The title is a neologism attributed to his contemporary, Ali Shariati, commonly rendered as “Occidentosis” in English. The essay is an anti-Shah polemic in which he indicts what he sees as the false consciousness of the colonised, for which Islam is the cure.

For Al-e Ahmad, Islam only attained its full form once it reached Iran and was no longer the sole province of the Arabs in what he calls their “primitiveness.” For him, the Western encounter with the Middle East was an assault on the region’s “Islamic totality.” Al-e Ahmad’s understanding of Islam’s place in the decolonial struggle is very different from that of Fanon, however. While Fanon acknowledges that in parts of the Arab world, “the national liberation struggle has been accompanied by a cultural phenomenon known as the awakening of Islam,” he also writes that, for an Algerian struggling for freedom for his country “no appeal to Islam or to the promised Paradise can account for [his] self-sacrifice.” For Fanon, the return to Islam was a consequence rather than a condition of collective revolt—a cultural resurgence produced by the struggle, but not its ideological engine. For Al-e Ahmad, Islam was the indispensable catalyst of liberation without which emancipation from Western domination would have been inconceivable. “If the Christian West, faced with overthrow and extinction at the hands of Islam, could suddenly awaken, dig in, and fight back—ultimately delivering itself—then is it not now our turn to awaken to the danger of extinction at the hands of the West, to rise, dig in, and fight back?” The question is, of course, rhetorical. The work was later censored in Pahlavi’s Iran, but by then it had already reached a wide audience.

Before the 1967 Arab–Israeli War, many anticolonial thinkers implicitly accepted Jews as part of the wider struggle against Western imperialism. Fanon, for instance, referenced the continued payment of German reparations to the State of Israel as a model for why the colonised should neither relent nor moderate their demands in the face of the colonial oppressor. Al-e Ahmad’s own vision of what Iran might become under renewed Islamic stewardship was shaped in part by a trip to Israel in 1963.