Free Speech

The Uninvited Sermon

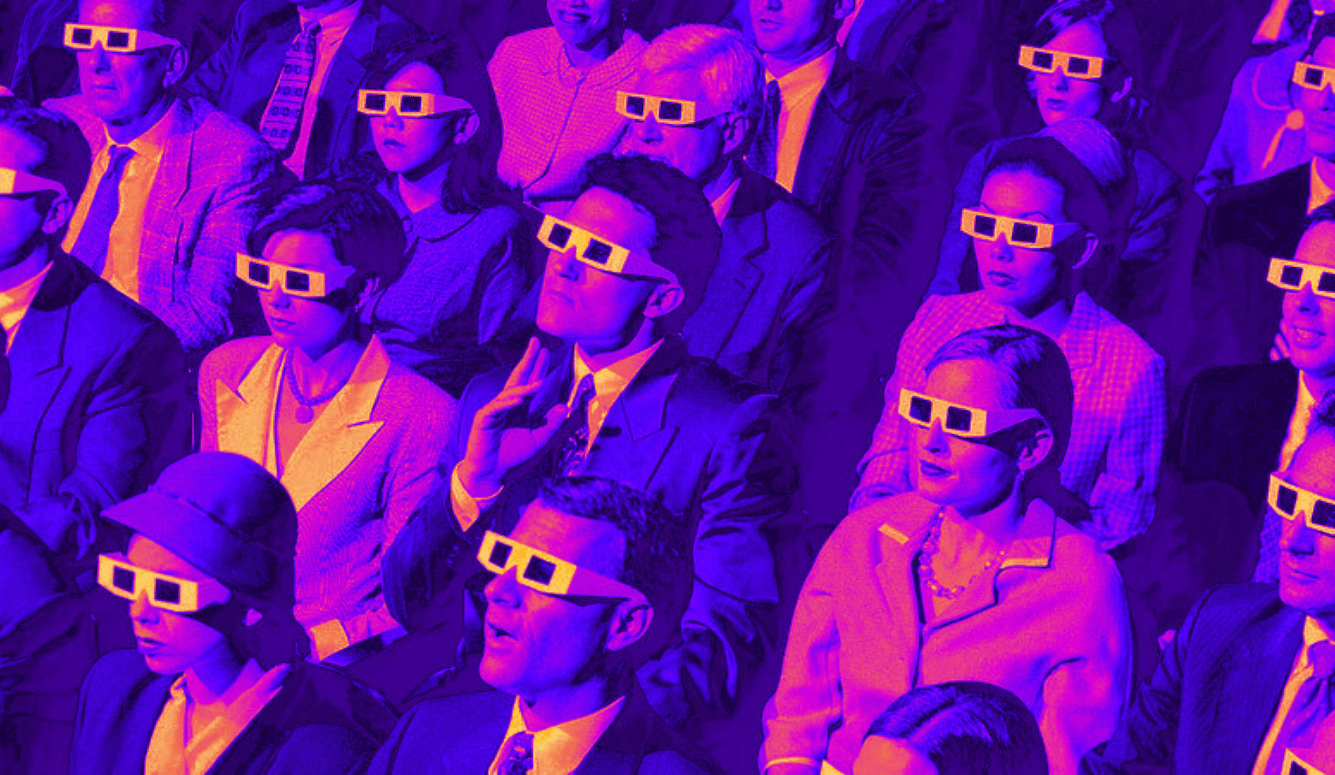

Why artists, academics and others should not exploit the presence of a captive audience.

I acquired the concept of a “captive audience” only a few months ago, thanks to one of the students in my free speech and hate speech class. The student had been following the controversy surrounding Jayson Gillham, a pianist contracting with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra (MSO). Gillham used some of his time during a recital to make remarks about Israel’s “targeted assassinations of prominent [Palestinian] journalists.” In response to complaints from members of the audience, the MSO made a statement describing Gillham’s conduct at the recital as “an intrusion of personal political views.” Gillham, who is now suing the MSO for wrongful dismissal, posted to social media: “I am fighting for freedom of expression for all artists… and for the right of all employees and contractors to express their political belief in the workplace without fear of discrimination.” In the MSO’s view, Gillham did something unprofessional, hijacking the recital in order to do personal advocacy. In Gillham’s view, he did not, because everyone should be free to bring their politics to work, and that’s exactly what he was doing.

Sophie Galaise was the orchestra’s managing director at the time. She was sacked shortly after distancing the MSO from Gillham. In an interview with The Australian, she said that she thought music concerts should be “safe havens” from politics because they are for all Australians (who, obviously, disagree about politics); and that “she and her management team were right to demand audience members be free to listen to music without being subject to political lectures.” Or as Alexander Voltz wrote in Quadrant (quoting Rachael Kohn), while artists are “free to contribute to political debate in the public square, they are not free to exploit a ‘captive audience,’ who have paid to see them perform a specific role.” The exploiting of a captive audience is already commonplace with acknowledgements of country (try going to any event at the Melbourne Comedy Festival without hearing one), but these, at least, are typically short and generally expected. Gillham’s remarks were neither—and they were the preface to a politicised piece of music that had not been announced in advance and that did not fit with the rest of the recital.

My first captive audience experiences—not that I knew the term for them then—began back during Edinburgh Fringe Festivals in the early 2010s, when events advertised as comedy shows turned out to be the comedians’ public trauma therapy, where audience tears of empathy or solidarity were more appropriate than tears of laughter. (One of those, Richard Gadd’s recounting of his rape, was a precursor to the hit Netflix show Baby Reindeer). Or the “comedy” would turn out to be a left-wing TEDx talk, where instead of laughter there would be clapping and approving nodding. (I have in mind people like Nish Kumar and Josie Long.) The show that really stands out in my memory is Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette, which I made the mistake of taking a depressed friend to in the hopes of cheering him up. Captive is precisely how I felt, knowing that it would be exceptionally rude to negotiate an escape (“Excuse me! Sorry!”) from a mid-row seat in a crowded theatre amid Gadsby’s performative emoting about growing up gay in Tasmania.

My most recent experience of this phenomenon, though, happened where I least expected it: at a day-long symposium on academic freedom, organised by the Australian Academy of the Humanities.

I’ve certainly felt trapped at academic events before, a recent memorable occasion being a one-and-three-quarter hour long departmental seminar by a visiting speaker who made it clear within the first three or so minutes that he would not be bothering to make the talk comprehensible to anyone outside his exceptionally narrow area of expertise (which was shared by exactly one other person in the room). But boring, inaccessible, and impenetrable are all within the bounds of what you can expect from academic seminars. You hope for the best and plan for the worst.

By captive I have something different in mind, namely being subject to something very different to what you signed up for. I have written elsewhere about the surreal experience of attending a symposium billed as being about academic freedom, that yet somehow managed to evade almost any real confrontation with the threats to academic freedom that exist for contemporary Australian universities. My focus here is on one talk in particular, the vices of which illustrate perfectly one such threat.

The talk was by a historian named Yves Rees, a biological female who identifies as nonbinary and who, at the tender age of 33 and only having claimed a trans identity a few years earlier, nonetheless published a memoir about her experience.