Politics

The New Speech Wars

At this year’s Global Free Speech Summit, there was a widespread sense that the US is at a perilous juncture.

During the free-speech skirmishes of the last decade, the battle lines were often drawn in a way that placed heterodox liberals and centrists on the same side as conservatives in opposing censorious progressivism. But those lines have been redrawn in recent months, after the Trump administration began aggressively targeting disfavoured expression, from overly negative museum exhibits on slavery to uncouth reactions to the murder of Charlie Kirk. Much of a triumphalist Right has now enthusiastically embraced the “cancel culture” it once condemned, embracing many of the same justifications once employed by the Left (censorship, we are told, is merely “accountability”). The heterodox community, defined by dissent from the progressive consensus on identity and social justice, has split into those whose defence of free speech extends to the Trump administration’s abuses and those who still prefer to fight various iterations of “wokeness.” Some leftists, meanwhile, have accused anti-Trump centrists of helping to “legitimise” him when they criticise the illiberal Left.

All these conflicts and realignments made it a particularly fitting moment to hold a “Global Free Speech Summit” at the start of October at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. This is the home of The Future of Free Speech, a think tank founded by Vanderbilt professor Jacob Mchangama, a Danish-born lawyer, scholar, and author.

The summit has been envisioned as an annual event. Now in its second year, it was co-sponsored by Heterodox Academy, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, and the Freedom Forum and Knight Foundation, and it drew an impressive variety of speakers and perspectives. These included a satellite interview with an Afghan woman involved in the underground education of girls (the highlight of which, perhaps, was her disdainful huff when she was asked what she would like to say to the Taliban). There was also a talk by a Sri Lankan comedian who spent more than a month in jail after being charged with “words intended to wound religious feelings” for joking about religion.

The international experience certainly helps put America’s problems in perspective. And yet, there really was a widespread sense among American speakers that the US is at a perilous juncture. As Mchangama put it: “Unfortunately, as we see, cultural institutions, law firms, and media outlets voluntarily cave to the pressure of the Trump administration, even though they could rely on the strongest free speech protection in the world.” This acquiescence, he added, is “an affront to dissidents in Iran and Russia who cannot rely on that protection”—a compelling point, especially in the wake of earlier summit panels that examined the daunting challenges to dissent and to the free press under authoritarian or totalitarian regimes. (Panelists included Alsu Kurmasheva, a Russian-American journalist for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty who was arrested while working in Russia in October 2023 and later sentenced to six and a half years in a penal colony for “spreading false information about the Russian Army”; fortunately, she was released in a prisoner exchange in August 2024.)

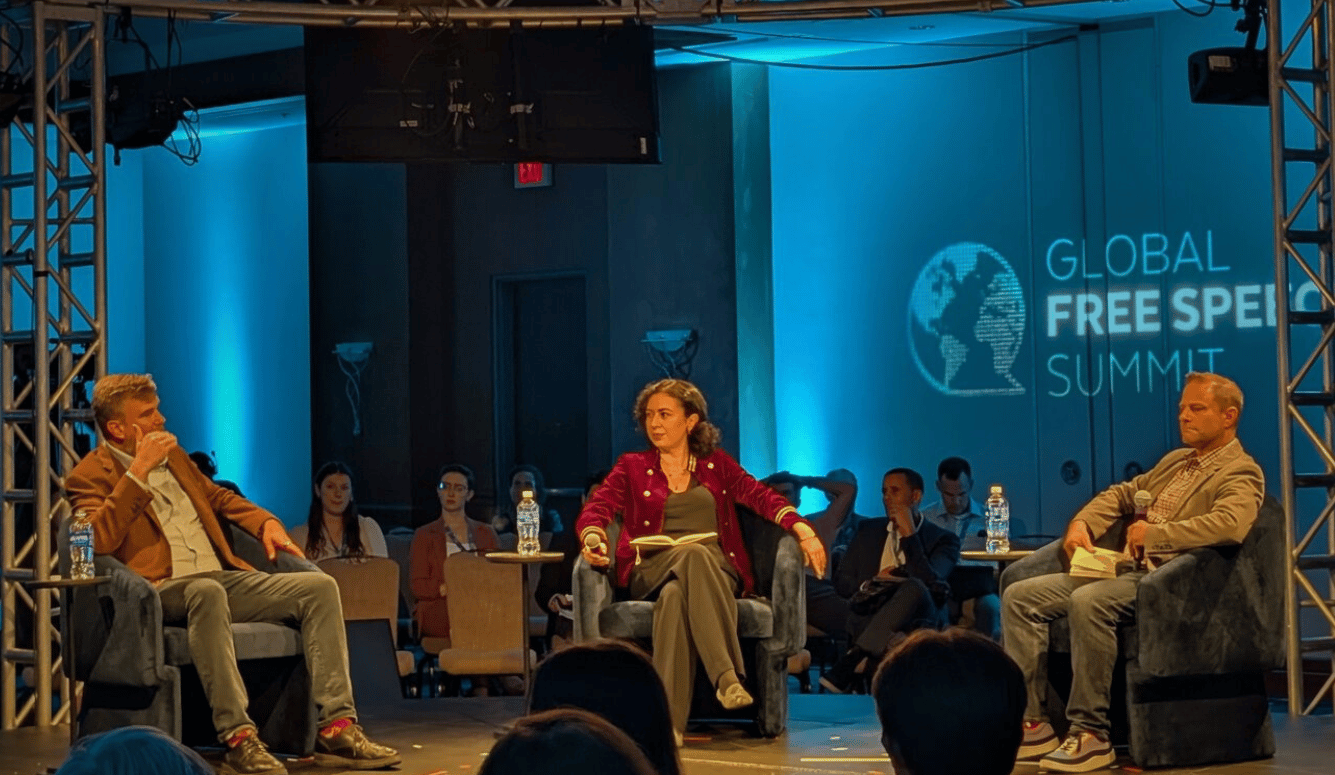

Mchangama’s observation was made during a discussion about free-speech hypocrisies (also recorded as a Persuasion podcast) in which three of the four panelists had been strong critics of progressive illiberalism: Mchangama himself, Persuasion magazine founder and editor-in-chief Yascha Mounk, and Brookings Institution fellow Jonathan Rauch, whose critique of progressive speech-policing, Kindly Inquisitors, appeared in 1993. Now, he is adamant that speech-policing by the government is unequivocally worse: “I would argue it is an order of magnitude more concerning because government can yank your license, investigate you, try you, put you in jail.” We have seen, for instance, television networks being dragged into a Trump-friendly orbit through a combination of bogus lawsuits from Trump and strong-arming by the Federal Communications Commission via its power to regulate media-company mergers. Rauch expressed his dismay at “how quickly we are moving toward Hungary,” where Viktor Orbán’s ruling party has consolidated much of the media landscape in its hands through a combination of direct government control and ownership by Orbán cronies. Except that, Rauch said, America’s slide toward authoritarianism-lite has been happening “on a very fast time scale”—it is already perhaps halfway there after only eight months of Trump’s second term, compared to the fifteen years it took Orbán. It’s not creeping Orbánisation so much as galloping Orbánisation.