literature

The Line Dividing Good and Evil

What we can learn from the moral and literary failings of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and James Baldwin.

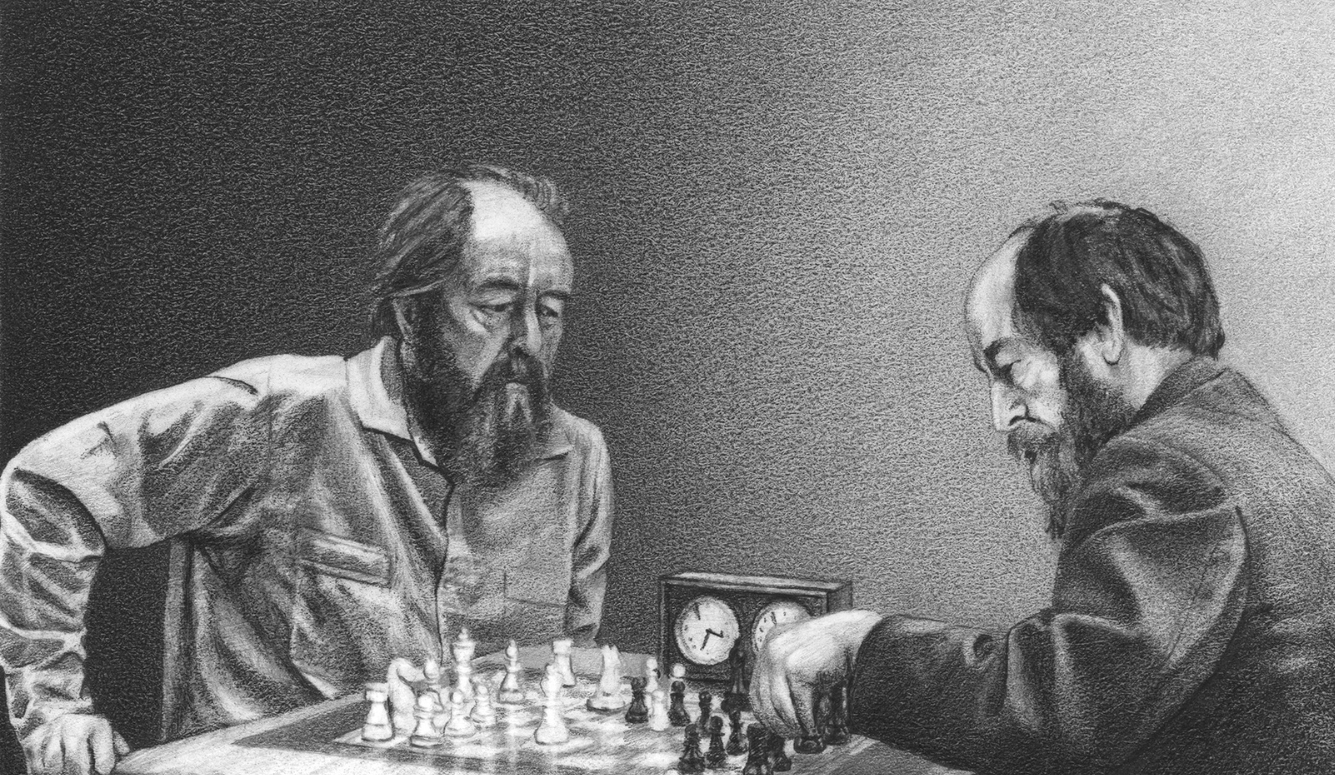

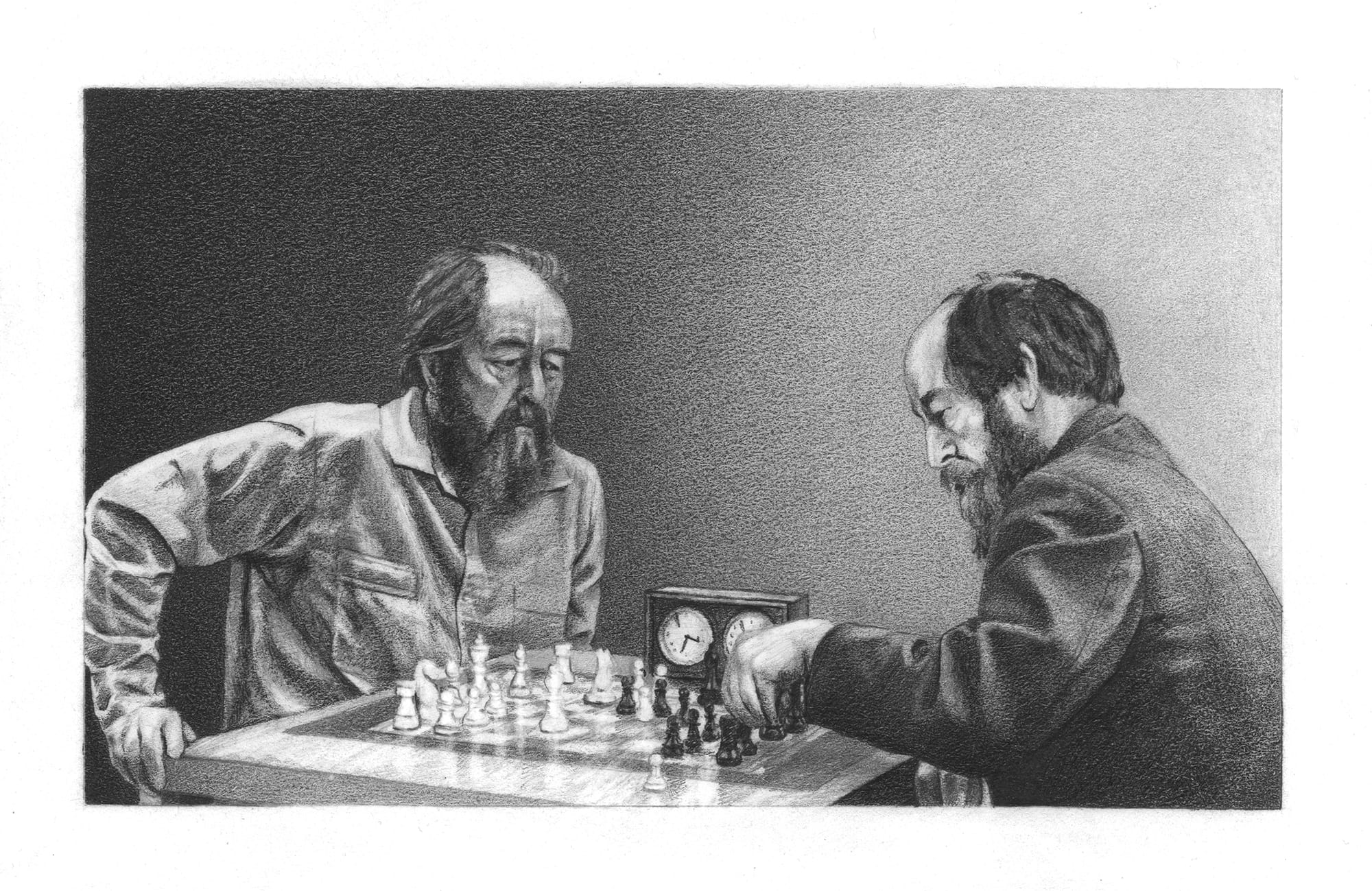

In his 1973 account of the Soviet prison system, The Gulag Archipelago, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn memorably cautions:

If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?

Even Solzhenitsyn himself failed to excise the evil in his own heart. By the end of his life in 2008, he had betrayed the values that once made him a hero among Soviet dissidents by embracing Vladimir Putin, even as the former KGB agent rehabilitated Joseph Stalin’s legacy. Solzhenitsyn was also prejudiced against groups that the Soviets had brutalised, particularly the Jews and Ukrainians. His own life story exemplifies his famous insight that good and evil coexist within us all—our heroes are not immune.

In her 2018 profile of Solzhenitsyn for Quillette, Russian-born American journalist Cathy Young describes “the fall of a prophet.” His former friends and fellow survivors “assailed Solzhenitsyn for positioning himself as a prophet of ‘God’s truth’ and trying to replace one form of groupthink with another,” writes Young, and “lambasted Solzhenitsyn as a ‘true Bolshevik’ of a different stripe.” Young describes her own dismay that “the man who exposed the full horror of Stalin’s rule had nothing to say about the creeping rehabilitation of Stalin on Putin’s watch”:

Solzhenitsyn was once my childhood hero. Growing up in the Soviet Union in the 1970s, in a family of closet dissidents, I knew him as the man who defied the system and told the truth about its atrocities—the man idolised by my parents, especially my father, himself the son of gulag survivors. I was eleven when Solzhenitsyn was arrested and expelled from the Soviet Union; our Stalinist political instructor at school bellowed that he should have been shot as a traitor. A year or two later I heard excerpts from The Gulag Archipelago on foreign radio broadcasts; then, the coveted book appeared for a short while in our home.

Later, after my family emigrated to the United States in 1980, Solzhenitsyn’s heroic halo gradually began to lose its lustre in our eyes. We were hardly alone; as the years went by, many of his erstwhile admirers came to believe, with bitter disappointment, that Solzhenitsyn could no longer be seen as a champion of freedom and justice.

In the end, the evil in Solzhenitsyn’s heart outplayed the good. This should humble everyone, especially when few have achieved anything as great as writing The Gulag Archipelago. As Young reminds us,

None of that lessens what Solzhenitsyn accomplished. One of millions who survived the infernal machine of Stalin-era “correctional labour camps,” he turned that ordeal into literature. [The effects of his] short novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich … were explosive: while Stalin’s Great Terror had been discussed before, its victims had never been so powerfully brought to life. … [The] masterwork forever associated with his name, the nonfiction epic The Gulag Archipelago, based in large part on the thousands of letters to Solzhenitsyn and to Novy Mir with first-person accounts by former prisoners [made the gulag] internationally known as a symbol of totalitarian evil.

Young recommends that we consider Solzhenitsyn’s life primarily as a cautionary tale “in an era when anti-liberal movements are surging on both the Right and the Left.” And this is the key lesson: Solzhenitsyn urged us to grapple with our own capacity for evil, and then demonstrated that such introspection cannot guarantee virtue.

If only discovering wisdom were enough to make us live by it! The sly devils in our hearts would like us to believe that recognising their existence will be enough to keep them in check. Time and again, the wise succumb to the same dangers they themselves once warned against, in the manner of Nietzsche’s ominous aphorism: “He who fights with monsters should see to it that he himself does not become a monster. And if you gaze too long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.”

A contemporary of Solzhenitsyn’s from the other side of the Cold War shared the Soviet dissident’s appraisal of the human heart. In his 1961 essay “The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy” (later published in the anthology Nobody Knows My Name), James Baldwin observes that “Nobody is more dangerous than he who imagines himself pure in heart, for his purity, by definition, is unassailable.” Baldwin was one of the greatest American essayists and civil rights activists—yet like Solzhenitsyn’s, Baldwin’s wisdom failed to save him from his inner demons.

As a young man under the boot of Jim Crow, Baldwin left America in disgust and travelled to Paris. But to his surprise, he came to be “released from the illusion that I hated America” when he met other expatriates there. In his 1959 essay for The New York Times “The Discovery of What It Means to Be an American,” Baldwin explains:

I left America because I doubted my ability to survive the fury of the color problem here. (Sometimes I still do.) I wanted to prevent myself from becoming merely a Negro; or, even, merely a Negro writer. I wanted to find out in what way the specialness of my experience could be made to connect me with other people instead of dividing me from them. …

In my necessity to find the terms on which my experience could be related to that of others, Negroes and whites, writers and non-writers, I proved, to my astonishment, to be as American as any Texas G.I. …

The fact that I was the son of a slave and they were the sons of free men meant less, by the time we confronted each other on European soil, than the fact that we were both searching for our separate identities. When we had found these, we seemed to be saying, why, then, we would no longer need to cling to the shame and bitterness which had divided us so long.

It became terribly clear in Europe, as it never had been here, that we knew more about each other than any European ever could.

The young Baldwin overcame the Manichean mindset that living under Jim Crow had encouraged, and then brought his nuanced perspective to bear on his literature—for a time. As Samuel Kronen chronicles in his 2021 Quillette piece, “James Baldwin and the Trouble with Protest Literature,” Baldwin was a better writer during the period when he rejected bitterness. Kronen describes how Baldwin vacillated “between moralism and humanism” despite having already clearly identified the problems with moralism as a young man:

The first article he published upon arriving in Paris was entitled “Everybody’s Protest Novel”—an essay that would establish Baldwin’s possibilities and foreshadow his limitations. It takes aim at the tendency to dramatise social issues through literature in racial terms for political purposes. This, he argued, ultimately reinforces the very principles which activate the oppression such writing is meant to protest. It relies upon the same moral logic of blackness and whiteness, damnation and salvation, good and evil, and cross-generational guilt and innocence from which the whole problem of race and racism came about in the American context. …

Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Baldwin wrote, was activated by “a theological terror … and the spirit that breathes through this book, hot, self-righteous, fearful, is not different from that spirit of medieval times which sought to exorcise evil by burning witches; and is not different from that terror which activates a lynch mob.” In order to fire the reader’s indignation, Stowe conceived Uncle Tom as a racial caricature of victimised innocence, “robbed of his humanity and divested of his sex.” This revealed the goal of the protest novel to be “something very closely resembling the zeal of those alabaster missionaries to Africa to cover the nakedness of the natives.”

The protest novel suggests that it is as simple as separating evil people from the rest of us and destroying them. It encourages us to imagine that some people can be unassailably pure in heart. And unlike Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, the protest novel cannot bring victims to life, because it sacrifices them to make a point. Harriet Beecher Stowe sacrificed her characters by leaving, as Baldwin put it, “unanswered and unnoticed the only important question: what it was, after all, that moved her people to such deeds.” As a result, Kronen writes, “The book is now more famous for the stereotype it ushered in than the war it began.” Protest novels are moralistic rather than realistic, so their characters are symbolic rather than life-like. When readers can’t peer into the inner life of the characters, the characters don’t feel real. Because Baldwin at first eschewed the protest novel, Kronen writes that:

Baldwin showed immense promise. To many observers, here was someone capable of using the background of his own particular experience to grapple with universal human truths regarding one of the most significant issues in the most powerful country in the world. But that’s just not what happened. Rather, Baldwin moved back to the States, became a key figure in the civil rights struggle, and ultimately gave up literary nuance in favour of political clarity. As the writer Shelby Steele puts it, “in blatant contradiction of his own powerful arguments against protest writing, [Baldwin] became a protest writer. There is little doubt that this new accountability weakened him greatly as an artist. Nothing he wrote after the early 60s had the human complexity, depth, or literary mastery of what he wrote in those remote European locales where children gawked at him for his color.”

And although Baldwin’s “unignorable orations almost certainly contributed to the success of the civil rights movement” and he “took personal risks, made tremendous sacrifices, and paid a steep price for it all”:

the decision to return to America and engage in activism took its effect. Baldwin’s earlier appeals to transracial humanism gave way to an intense, unrelenting, and deeply racialised moralism, and by the end of his life he seemed to resign himself to the idea that white people were simply insane. (“For, in the generality, as social and moral and political and sexual entities, white Americans are probably the sickest and certainly the most dangerous people, of any color, to be found in the world today.”)

Although Baldwin never lost his gift for elocution or his insight into human psychology, it’s difficult to deny that his writing on race in particular grew increasingly bitter over time. He never came to appreciate, or hardly even acknowledge, the major social changes that occurred in his lifetime and which his own work had inspired. Considering what actually happened in America between Baldwin’s birth in 1924 and his death in 1987, this omission is a tell (one of his least favourite terms was “progress”).

Part of the problem may be that awareness of our past wisdom can turn us into present fools. If we know that we have been sage in the past—as both Baldwin and Solzhenitsyn were for significant parts of their lives—then we may begin to trust ourselves too much. We may fantasise that we have destroyed the evil in our own hearts, while holding those who haven’t in contempt.

Therefore, we should cherish our fallen prophets, however much they disappoint us. They teach us that purity eludes even the best of us, so that maybe we’ll hesitate before casting the first stone. Fallen prophets show us that there is a demonstrable answer to Solzhenitsyn’s question: No one has ever cut out a piece of his own heart, and neither will we.