Politics

The Limits of American Progressivism

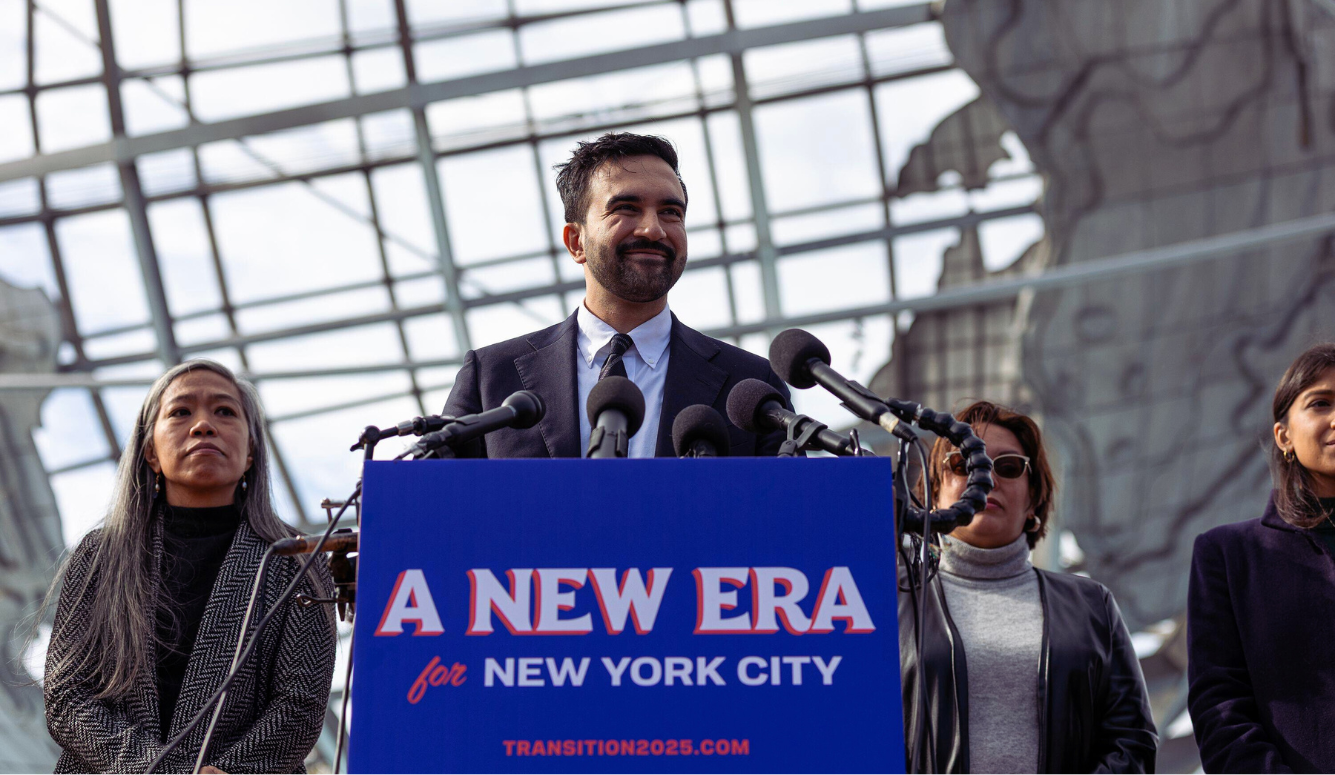

History and the constraints of American federalism suggest the euphoria and catastrophism that have followed Zohran Mamdani’s election victory are misplaced.

When New Yorkers elected Zohran Mamdani as their mayor on 4 November, many commentators and politicians treated the result as a political earthquake. In his victory speech, Mamdani also adopted the language of epochal change. “New York will remain a city of immigrants,” he told supporters, “a city built by immigrants, powered by immigrants, and as of tonight, led by an immigrant.” Then, quoting Jawaharlal Nehru, he cast his election as a wild new watershed: “A moment comes, but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new. … Tonight, we have stepped out from the old into the new.”

For progressives, Mamdani’s rhetoric was exhilarating. The Guardian’s Margaret Sullivan reported that his message possessed “a clarity that stands in sharp contrast to most Democratic politicians,” while others on the Left saw his win as proof that the city’s younger voters—many of whom are renters struggling with the cost of living—were finally asserting themselves against decades of failed centrist compromise. On the Right, meanwhile, people reacted with the same intensity but the opposite emotion. Republican Representative Nicole Malliotakis spoke for many conservatives when she warned that the result would be “a disaster.” Her mother, she added, “fled communist Cuba to not live in a communist New York.” President Trump went further, calling Mamdani “a 100% Communist lunatic” and predicting economic ruin (although he hasn’t given Mamdani a Trump nickname yet).