Art and Culture

Ballad of a Song and Dance Man

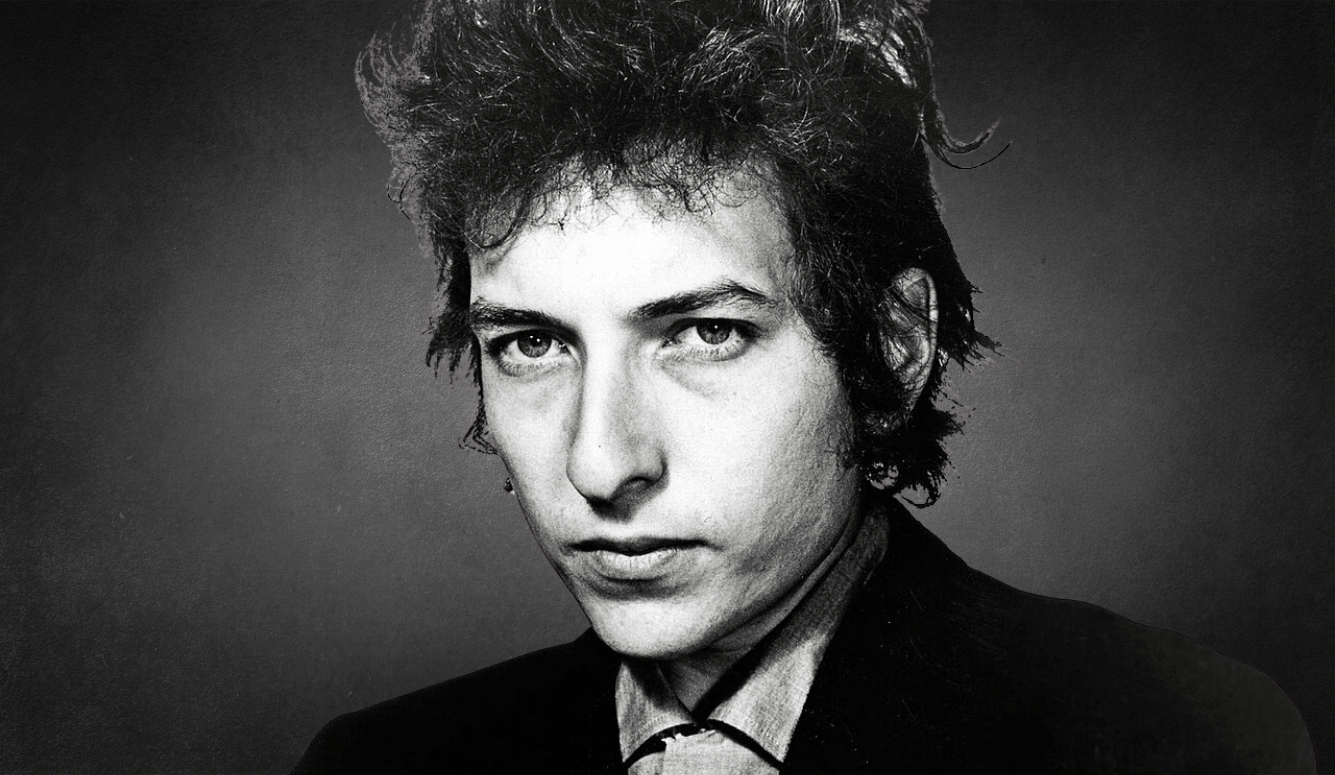

An unorthodox new book by one of America’s finest nonfiction authors tries to make sense of Bob Dylan.

A review of Bob Dylan: Things Have Changed by Ron Rosenbaum; 287 pages; Melville House (October 2025)

Ron Rosenbaum is one of America’s finest nonfiction authors. His bestselling book Explaining Hitler—an exploration of how and why Hitler became a monster, which I read when it was published in 1999—established its author as a master of cultural history. This time, Rosenbaum has turned his attention to Bob Dylan, a contemporary figure who might be the most influential and important songwriter in American history. He is, to date, the only one to be honoured with the Nobel Prize for literature. Rosenbaum has subtitled his book “A Kind of Biography.” This, he explains, “is less a formal biography than a biography of [Dylan’s] impact on the consciousness of the culture.”

Rosenbaum’s book is also a good deal more critical and less reverential than many of the books celebrating Dylan’s life and work. In a 2011 article for Slate, Rosenbaum expresses his frustration with those Dylan disciples he describes as “Bobolators”—“writers and cultists who still make Dylan into a plaster saint, incapable of imperfection.” Bobolators, he complains, “diminish The Bob’s genuine achievements by putting everything he’s done on the same transcendentally elevated plane. With their embarrassing obeisance, their demand for reverence, their indiscriminate flattery, they obscure the electrifying musical—and cultural—impact he’s actually had.” Rosenbaum confesses that he was once one of them until he grew out of it, but that this affords him a unique perspective on Dylan’s life and work:

I don’t regret having become a Bobolator; I would have never come close to understanding Dylan without understanding—experiencing—that which gives rise to Bobolatry. But I would have never been able to write about him without discarding Bobolatry for something more, something that incorporates the ability to make distinctions, which is the essence of “the palace of wisdom.”

I come to you with humility and dawning wisdom as a recovering Bobolator.

What we get from Rosenbaum, then, is an unorthodox meditation on the meaning of Dylan as an artist and an individual. Rosenbaum seeks to understand his subject by looking at the songs he wrote at different stages of his life and divining the subtextual meaning that may not be immediately apparent when we read the lyrics on paper or hear them on record. He invites us to reconsider Dylan’s songs in the context of what the artist was living through and experiencing when he wrote them. Rosenbaum has clearly read many of the books already written about Dylan, but he offers us his own unique take on the man and his work. The only other book that attempts something similar is Greil Marcus’s brilliant Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs, published in 2022.

I.

Dylan grew up as one of the few Jews in Hibbing, Minnesota; a bar mitzvah boy whose father had to hire a Rabbi from Brooklyn to come to their small town and train young Bob for the occasion. Dylan could read Hebrew and went to a Zionist summer camp when he was a youngster. But as his fame grew, he became weary of fielding questions from journalists about his Jewishness and the Hasidic tales that supposedly explained his songs. What really lies at the heart of Dylan’s music, Rosenbaum argues, is an obsession with “the persistence and presence of catastrophic evil and suffering in human affairs.” Rosenbaum believes that Dylan’s “rage at the Old Testament God for His apparent indifference in the face of evil” is part of what led him to reject Judaism and convert to Christianity in the late 1970s.

In addition to this disenchantment with Judaism, Rosenbaum points out that Dylan’s conversion was motivated by the need to seek relief from the emotional turmoil and distress into which his personal life had slumped. In November 1977, Rosenbaum spent seven days interviewing Dylan as he struggled to edit miles of footage shot during the 1975–76 Rolling Thunder Revue tour into a comprehensible feature film. The upshot was a four-hour experiment (Rosenbaum calls it Dylan’s “cinematic masterpiece”) titled Renaldo and Clara starring Dylan’s wife Sara and his former lover Joan Baez. Dylan’s marriage was already falling apart while the film was being made, and after the couple divorced in June 1977, he was tormented by loneliness and despair. He would later claim to have seen a vision of Jesus in a Tucson motel room on a November night in 1978, and the following year, he announced his conversion to Christianity with the release of his first evangelical album Slow Train Coming. Born again, his new faith seemed to reinvigorate him.

But Rosenbaum argues that the effects of this conversion were almost entirely negative. They allowed Dylan to be exploited by “Jesus-freak brainwashing” fanatics who almost “killed his career, obscured his impact, and bankrupted his cultural capital.” Rosenbaum condemns the “rock critic sycophants” who “were disgracefully unwilling to come out and say what a terrible thing happened when this self-described Christian cult—the Vineyard Fellowship—got hold of a vulnerable Jewish soul” and sent Dylan into a “death spiral” of “robotic dogmaspouting.” Dylan’s conversion also offended Rosenbaum as a Jew. “[I]t just seemed so unnecessary,” he writes, “for a post-Holocaust Jew who didn’t like Jahweh to announce his enslavement to Jesus.”

Dylan began preaching during his concerts, and Rosenbaum calls these recordings “sermonizing tapes, which seemed like self-criticism sessions not unlike the dogmatic North Korean Marxism of The Manchurian Candidate. It was the Manchurian Dylan!” Watching these hectoring rants was like watching someone “mechanically, robotically mouthing apocalyptic New Testament prophecies as if in some mind-control trance.” On 26 November 1979, for example, Dylan told attendees at a gig in Tempe, Arizona:

Well, let me tell you, that the devil owns this world. He’s called the God of this world. Now we’re living in America. I like America just as much as everybody else does. I love America, I gotta say that. But America will be judged. You know, God comes against a country in three ways. First way he comes against them, he come against them in their economy. Did you know that? He messes with their economy the first time. You can check it all the way back to Babylon, and Persia and Egypt. Many of you here are college students aren’t you? Many of you are college students. You ask your teachers about this now. You see, I… uh... I know they’re gonna verify what I say. Every time God comes against a nation, first of all he comes against their economy.

The audience had to listen to more than five minutes of this before Dylan and his band finally launched into “Solid Rock,” an unreleased song from his second evangelical album Saved, which would not be available until the following year. Not everyone who had paid to hear Dylan perform his music took kindly to this sort of thing, and he began to annoy and lose his audience. Rosenbaum concedes that Dylan’s Christian period did produce “maybe three” good songs—the “sinister, serpentine” title track on Slow Train Coming; “Precious Angel” (“a genuine love song without dogma”); and “Every Grain of Sand” (a “nondenominational but emphatically spiritual” fan favourite that he still performs today). But Rosenbaum basically considers this period of Dylan’s career a dead loss, and rightly laments that “they turned him into a puppet for a New Age Christian group whose logo was a line drawing of Jesus resembling a benevolent Marin County coke dealer.”

Thankfully, Dylan’s infatuation with Christianity burned itself out within a few years. Some time in the early ’80s, I was speaking to Harold Leventhal, the music agent who represented Pete Seeger and other artists, and I asked him what he thought about Dylan’s Christian conversion. He told me that he and Seeger had just returned from visiting Dylan in California, and while they were there, Leventhal had said: “Bob, there’s one thing I don’t get, and that is your proselytising for Christ. You’re as Jewish as anyone else I know. When are you going to give up this Christian stuff?” Dylan replied, “Don’t worry, Harold, I’m through with that. You’ll soon see.” Dylan recorded just three overtly evangelical records—Slow Train Coming in 1979, Saved in 1980, and Shot of Love in 1981. After that, the religiosity subsided, the preaching at concerts ended, and he turned his attention to other things.

Rosenbaum believes that Dylan’s song, “Mississippi,” from his 2001 album “Love and Theft”, is a rueful reflection on his misspent evangelical years. According to this reading, the US state notorious during the pre-civil rights era as a place of “shackles and enslavement” serves as an allegory for Dylan’s “mental state of enslavement: the period when Dylan was shackled to born again dogma of the most rigorous, self-righteous, and sterile sort.”

Well, the emptiness is endless, cold as the clay

You can always come back, but you can’t come back all the way

Only one thing I did wrong

Stayed in Mississippi a day too long

II.

Rosenbaum spends some time discussing Dylan’s politics and speculates that Dylan was dismayed that his songs and persona were appropriated by the most extreme elements of the ’60s New Left. The Weather Underground (formerly the Weathermen) was a radical terrorist organisation that grew out of the collapsing Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and took their name from a line in Dylan’s 1965 song “Subterranean Homesick Blues”: “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.” On 5 May 1970, an explosion on 11th Street in an exclusive section of the West Village killed three members of the group. They had been preparing bombs to be planted at a welcoming dance for new soldiers at an army base in Fort Dix, New Jersey. Instead, they blew up themselves and the building they were living in—a townhouse belonging to the rich parents of one of the Weather Underground’s members, who were on vacation at the time.

In response to this debacle, the group re-evaluated the tactics it was using to pursue communist revolution. On 6 December 1970, the Weather Underground released a statement announcing a new attempt to build a mass-movement against the Vietnam War. Invoking Dylan again, they titled their communiqué “New Morning” after the title track of the album Dylan had released just a couple of months earlier. These references to Dylan’s songs and lyrics created the false impression that he was somehow connected to their movement or identified with it, when he actually “had nothing to do with it and in fact when asked refused to state his position on the war.”

During an interview for the folk-music magazine Sing Out! in 1968, Dylan spoke to his friends John Cohen and Happy Traum about antiwar activism, and his reluctance to be roped into political causes or boxed into political positions is evident from the transcript:

Traum: Probably the most pressing thing going on in a political sense is the war. Now I’m not saying that any artist or group of artists can change the course of the war, but they still feel it their responsibility to say something.

Dylan: I know some very good artists who are for the war.

Traum: Well I’m just talking about the ones who are against it.

Dylan: That’s like what I’m talking about; it’s for or against the war. That really doesn’t exist. It’s not for or against the war. I’m speaking of a certain painter, and he’s all for the war. He’s just about ready to go over there himself. And I can comprehend him.

Traum: Why can’t you argue with him?

Dylan: I can see what goes on in his paintings, and why should I?

Traum: I don’t understand how that relates to whether a position should be taken.

Dylan: Well, there’s nothing for us to talk about really.

Cohen: Someone just told me that the poet and artist William Blake harbored Tom Paine when it was dangerous to do so. Yet Blake’s artistic production was mystical and introspective.

Traum: Well, he separated his work from his other activity. My feeling is that with a person who is for the war and ready to go over there, I don’t think it would be possible for you and him to share the same basic values.

Dylan: I’ve known him a long time, he’s a gentleman and I admire him, he’s a friend of mine. People just have their own views. Anyway, how do you know I’m not, as you say, for the war?

Dylan’s audience was familiar with “Masters of War,” one of his earliest and most pedestrian songs. That track and others from the same period forever burdened him with the “protest singer” label, but he was never comfortable with it. His friend Tony Glover once recounted that while visiting Dylan in New York, he found a draft of “The Times They Are A-Changin’” in the typewriter. Glover favoured authentic folk-blues and eschewed many of the era’s left-wing pieties. “What is this crap?” he asked. Glover said that Dylan replied, “I don’t know. I’m writing this stuff because that’s what my audience seems to like.” If that story is true and Dylan’s answer was sincere, then even his early protest songs were opportunistic.

Other incidents seem to confirm this. The most famous of these illustrates Dylan’s strained relationship with his friend from the same Greenwich Village circles, the radical singer and songwriter Phil Ochs. Ochs was known for writing politically oriented songs like “Love Me, I’m a Liberal” and “I Ain’t Marching Anymore,” an anti-Vietnam War anthem. During a cab ride somewhere, he and Dylan got into an argument about the purpose of their music. “You’re not a songwriter, Phil,” Dylan screamed at Ochs, “you’re a journalist!” After that putdown, Dylan ordered the cab to stop and demanded that Ochs get out. Ochs once called himself a “singing socialist.” Dylan preferred to describe himself as “a song and dance man.”

In his discussion of Dylan’s 2017 Nobel lecture, Rosenbaum notices something odd that many other commentaries on the speech failed to mention—the disappearance of Woody Guthrie as a formative influence. After all, Rosenbaum reminds us, Dylan came to New York City “to sing Woody; he came to seek Woody’s people, his disciples, at the center of the Woody cult in Greenwich Village. And to bond with Woody himself at Woody’s bleak bedside quarters in the charity hospital that was doing nothing (nothing was to be done at the time) for his wasting affliction with Huntington’s disease.” So why is Guthrie missing from Dylan’s lecture? Dylan, Rosenbaum notes, “decided to pull a fast one: to erase Woody from his initiation role, from his origins as a singer-songwriter entirely.”

Instead, Dylan began his lecture like this:

If I was to go back to the dawning of it all, I guess I’d have to start with Buddy Holly. Buddy died when I was about eighteen and he was twenty-two. From the moment I first heard him, I felt akin. I felt related, like he was an older brother. I even thought I resembled him. Buddy played the music that I loved—the music I grew up on: country western, rock ‘n’ roll, and rhythm and blues. Three separate strands of music that he intertwined and infused into one genre. One brand. And Buddy wrote songs—songs that had beautiful melodies and imaginative verses. And he sang great—sang in more than a few voices. He was the archetype. Everything I wasn’t and wanted to be. I saw him only but once, and that was a few days before he was gone. I had to travel a hundred miles to get to see him play, and I wasn’t disappointed.

He was powerful and electrifying and had a commanding presence. I was only six feet away. He was mesmerizing. I watched his face, his hands, the way he tapped his foot, his big black glasses, the eyes behind the glasses, the way he held his guitar, the way he stood, his neat suit. Everything about him. He looked older than twenty-two. Something about him seemed permanent, and he filled me with conviction. Then, out of the blue, the most uncanny thing happened. He looked me right straight dead in the eye, and he transmitted something. Something I didn’t know what. And it gave me the chills.

Dylan certainly approved the giant video of him talking about Guthrie that greets visitors to the Dylan Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma. And Dylan wanted his museum to be there, since he said Guthrie’s museum was there, so he had it built on the other side of the same building as Woody’s homage. In James Mangold’s 2024 biopic A Complete Unknown, “Song for Woody” is the first thing we see Timothy Chalamet play when he visits Guthrie in the hospital. Writing in Chronicles, Dylan says that Guthrie was “the starting place for my identity and destiny. ... My life had never been the same since I’d first heard Woody on a record player in Minneapolis. ... When I first heard him, it was like a million megaton bomb had dropped.” So Guthrie’s absence from Dylan’s Nobel address is deeply strange—an omission that Rosenbaum compares to “the poor apparatchiks Stalin erased from The Great Soviet Encyclopedia.”

But Rosenbaum points out that Buddy Holly’s songs “were always more intimate and lyrical than Woody’s anthemic bombast.” He thinks that Dylan drew from Holly “the intimacy, the sense of speaking softly to the heart of their listeners.” Before Dylan’s folk transformation after he heard Odetta, he had played in a high-school rock ‘n’ roll band called “The Golden Chords.” They played so loud at his high-school talent show that the principal shut down their act before they had finished their set. And under Dylan’s high-school yearbook photo, his goal was: “wants to be Little Richard.”

So Dylan was an apolitical rocker first and a political folkie second. But Dylan’s Nobel lecture suggests that Guthrie did not deserve “to be in the picture at all.” Perhaps, Rosenbaum surmises, Dylan did not want to be seen as a Guthrie clone or someone associated with radical politics, like his former friend and early promoter Pete Seeger. Perhaps, he speculates, Dylan “got tired of being seen as a satellite of the Communist Party.” Rosenbaum says he can “imagine Dylan thinking, ‘I’ve got to put a stop to all these academics trying to include me as a fellow traveler in their cultural Marxist analysis. I’m cutting Woody loose, and maybe they’ll get the message.’”

It is an interesting but perplexing thesis—Dylan’s musical debt to Guthrie is well-established and Dylan was never associated with the CPUSA, either in reality or in the public perception. As someone who followed his career from the very beginning and moved in the same circles, I can say with confidence that nobody ever thought of Dylan in that way, including those of us who were associated with the CP and its fellow-travellers. If anything, some of the people I knew complained because Dylan was not a part of it. A University of Minnesota student who was friendly with Dylan at the time told me how he often argued with Dylan and tried to introduce him to radical politics, but Dylan simply wasn’t interested. Later, he befriended and was mentored by the sometime-Trotskyist, sometime-anarchist blues and folk singer, Dave Van Ronk, but Van Ronk couldn’t interest Dylan in that stuff either. All Dylan says about Van Ronk in Chronicles is: “Van Ronk could talk about socialist heavens and political utopias—bourgeois democracies and Trotskyites and Marxists ... he could grasp all that stuff firmly.”

But while Dylan was not an orthodox leftist or a traditional antiwar activist, he was always keenly attuned to the horrors of war and the inhumanity of which man is capable. Towards the end of his book, Rosenbaum addresses the section of Dylan’s Nobel lecture in which he speaks about All Quiet on the Western Front, the famous World War I novel by Erich Maria Remarque:

This is a book where you lose your childhood, your faith in a meaningful world, and your concern for individuals. You’re stuck in a nightmare. Sucked up into a mysterious whirlpool of death and pain. You’re defending yourself from elimination. You’re being wiped off the face of the map. Once upon a time you were an innocent youth with big dreams about being a concert pianist. Once you loved life and the world, and now you’re shooting it to pieces.

Heavy stuff indeed. Remarque’s book displays the worst of mankind, and the human capacity for evil it conveys evidently shattered Dylan as a young man. Rosenbaum calls Dylan’s description of the book and its impact a “fierce piece of prose” in which “he impersonates Remarque’s fantasy of degradation, compresses the evil of war, the evil of the world.” He goes on to say that this amounts to “Dylan’s account of his visit to Hell, the way all epic heroes do—in the Odyssey, in Virgil, in Dante—an extended ode to death and corpse stench. He allows Remarque to inhabit him.” One might call this passage of Dylan’s speech a prose song, not yet set to music. It is, Rosenbaum feels, “a takeoff point for Dylan’s version of the Inferno” and “a scorching vision of Western civilization as a searing blast furnace of screaming armaments bent on murder.”

Rosenbaum reminds us that Dylan wrote those words about the novel “through the eyes of World War II and its Holocaust.” Rosenbaum believes that this was Dylan’s way of subtly rebuking Sweden for its neutrality in the war against Hitler. This nation has the chutzpah to bestow Nobel Prizes having been incapable of action in the face of abomination. He ends the passage with Dylan’s own words from “All Along the Watchtower”: “So let us not talk falsely now, the hour is getting late.”

III.

I will close this essay with a handful of criticisms, the first of which concerns me personally. Twice in the book, Rosenbaum talks about how I first met Dylan when he came to Madison, Wisconsin, in late winter of 1961. Rosenbaum writes that “Radosh still remembers when he got a call from a friend in antiwar circles at the University of Minnesota asking him if he could find a place for this kid folk singer to stay on his way to New York City.” Not true. Dylan phoned me from the bus station and told me he had got my phone number from Carl Granich, a guitarist from the NYC folk scene. The account of what Dylan said to me is correct—that he would be “bigger than Elvis” and would play “large arenas,” and as Rosenbaum reports, I did have the sense of speaking to “someone who had an uncanny sense of his destiny.” But Rosenbaum describes me as the “head of one of the most radical factions of SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) at the University of Wisconsin.” There was no SDS chapter at the university and the Weatherman faction (of which I was never a member) did not even exist then. You can find the most correct version of what happened in an article by journalist Kurt Stream in Madison Magazine.

Although Rosenbaum describes “The Times They Are A-Changin’’’ as “thrilling and prophetic,” he dismisses “Blowin’ in the Wind,” as “sappy” and “Kumbaya-like.” I agree that its lyrics are not as complex or mysterious as those Dylan would develop as a more experienced and sophisticated songwriter. But its simplicity is its power; it was the song that best confronted America with the brutal side of its own nature, from the shackles of slavery to the laws of Jim Crow, which were still enforced when Dylan wrote those famous words:

Yes, and how many years must a mountain exist

Before it is washed to the sea?

Yes, and how many years can some people exist

Before they’re allowed to be free?

Yes, and how many times can a man turn his head

And pretend that he just doesn’t see?

The song’s origin has been discussed many times by Bob Cohen and Happy Traum, who were part of the folk group the New World Singers in the early ’60s. They say Dylan borrowed the melody from an African-American slavery-era song titled “No More Auction Block for Me” that the New World Singers used to play, and that he played “Blowin’ in the Wind” for them one evening after they finished their set. Gil Turner, the third member of the group, then performed it at Gerde’s Folk City—its first public performance and the folk world’s introduction to the song. Joan Baez later heard Dylan sing it at Gerde’s, and she told a cab driver “I just listened to the best song I’ve every heard.” Baez said the driver thought she was crazy.

Rosenbaum unfairly criticises American historian Sean Wilentz, whom he accuses of trying to trace “Dylan’s vibe to the tedious, blaring work of popular front composer Aaron Copland.” Nothing, Rosenbaum argues, was further from Dylan’s mind than the “musical bloviation of Copland’s condescending ‘Fanfare for the Common Man.’” But in his magisterial book, Bob Dylan in America, Wilentz writes that when Dylan and his band were touring the Love and Theft album, the shows would open with a recording of the “Hoe-Down” section of Aaron Copland’s Rodeo before the band took the stage. And Wilentz doesn’t say what Rosenbaum reports. He wrote: “Copland’s music and persona had no obvious or direct effect on the kinds of music Dylan performed and wrote as a young man, but the broader cultural mood that Copland represented certainly did.” Like Dylan, Copland was charged with being commercial and a sell-out, and he too would “reshuffle the very terms on which American music could be composed and apprehended.”

Wilentz argues that, like Dylan, Copland’s art “was built partly out of old cowboy balls and mountain fiddle-times,” and that he “anticipated Dylan’s [music] in ways that help make sense of both men’s achievements.” By Dylan’s time, Copland had long broken with his leftist past, but Wilentz ties his 1940s music to the “populist adaptations of American folk music being undertaken by his friend Charles Seeger’s boy Pete and by Pete’s leftist folksinger friends.” And as we know, Dylan idolised Pete Seeger, who helped promote his career. Wilentz wisely notes that “Copland and his music shared political origins and sensibilities with the folk revival.”

I am also surprised that Rosenbaum leaves out an episode from 2011 when Dylan played in China shortly after news first emerged of the brutal suppression of the Uyghur population and other ethnic groups in the north-western region of Xinjiang. Writing in Slate at the time, Rosenbaum condemned Dylan for performing in Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong with what the Chinese authorities called “approved consent.” It appeared that the regime had vetted his setlist, and that Dylan had agreed not to sing certain numbers deemed to be “protest songs.” What, Rosenbaum asked, “happened to the spirit of ‘Ain’t Gonna Play Sun City’?” the resort in apartheid South Africa boycotted by Dylan and other artists.

Rosenbaum’s comments were nothing compared to those published by New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd, who ignited the controversy with a much-discussed op-ed, cruelly titled “Blowin’ in the Idiot Wind.” Dylan, she wrote, “sang his censored set, took his pile of Communist cash and left.” The excuse offered by zealous fans and Dylanologists was that music knows no political boundaries and its only message is art. In a rare public response, Dylan said that the Chinese regime asked what he would be singing, and he sent them three months’ worth of setlists instead. Rosenbaum rightly noted that this evaded the real issue; “not what he sang but whether he should be singing at the sufferance of torturers at all.”

Readers will find their own areas of disagreement with Rosenbaum’s analysis, especially when he singles out particular songs for praise or trenchant criticism. They will no doubt find many of his judgements sound and others wanting, which is always the way with a writer as opinionated as this one. Personally, I wish Rosenbaum had managed to include an analysis of Dylan’s great album Rough and Rowdy Ways and its epic seventeen-minute track about the Kennedy assassination, “Murder Most Foul.” It would have allowed Rosenbaum to show how that brilliant ballad fits with Dylan’s previous works, and how it makes sense of human evil—the theme that Rosenbaum identifies throughout Dylan’s work and that threads through his own book.

But these are minor gripes about an original and fascinating work about a major artist. So long as Bob Dylan’s health allows him to carry on trying to make sense of a dangerous world, Ron Rosenbaum’s book can help us to make sense of Bob Dylan.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this review stated that Rosenbaum had misidentified Woody Guthrie's “1913 Massacre” as the source of Dylan’s “Blowin’ In The Wind.” In fact, this was a mistake in the galley that was corrected in the hardback edition. Quillette regrets the error.