Israel

An Uneasy Peace

Trump’s peace plan brings the hostages home and halts fighting in Gaza, but Hamas’s refusal to disarm and Israeli concerns about Palestinian statehood threaten the deal’s long-term survival.

On Monday morning, Israeli Jews rejoiced as Hamas released the last twenty Israeli hostages from tunnels in Gaza, allowing them to return to their families and girlfriends. A few hours later, almost 2,000 Palestinians who had been imprisoned in Israel were released. Most of them returned to Gaza and the West Bank, though several dozen are destined to live out their lives in exile abroad. Of the Arabs released, some 250 were serving life sentences for murdering Israelis over the past thirty years.

Alongside the live hostages, Hamas have also handed over seven or eight bodies of hostages who died either during Hamas’s invasion of Israel on 7 October 2023 or in their subsequent captivity. According to President Donald Trump’s twenty-point peace plan, published on 29 September, and the Israel–Hamas agreement that followed, Hamas was supposed to hand over the bodies of 28 dead hostages—and Israel and Washington are now demanding that Hamas fulfil its commitment. Hamas officials have said that they are having difficulties locating the twenty missing bodies, some of which are presumably buried under the rubble of houses destroyed by Israeli bombings of the Strip over the past two years. But Israeli officials suspect that Hamas is playing games and is either bent on psychologically torturing the families of the twenty, who wish to bury their dead in Israel, or wants to hold onto the “missing” bodies in order to trade them for a release of additional Palestinian prisoners at a later date. On Tuesday, Israel threatened to respond to what it regarded as Hamas’s violation of the agreement by imposing restrictions on humanitarian aid entering the Strip or even closing the Rafah crossing between Egypt and Gaza—though it appears that neither penalty has actually been activated. On Wednesday, it appeared that Hamas intended to hand over four more bodies within hours. Egypt has announced that its agents are now working in the Strip, attempting to locate the missing bodies.

Monday’s hostage–prisoner exchange followed Saturday’s military withdrawal, as the IDF pulled its troops back eastward out of some twenty percent of the Gaza Strip, especially the outlying areas of Gaza City, the Strip’s main urban hub. The IDF continues to occupy about fifty percent of the Strip, areas it conquered during the counter-offensive that followed Hamas’s invasion of southern Israel on 7 October 2023, in which around 1,200 Israelis—350 of them soldiers—were murdered and 251 taken hostage. According to Hamas figures, some 67,000 Gazans were killed over the following two years of warfare in the Strip, about one-third or one-quarter of whom—according to Israel—were Hamas fighters. The rest were civilians who died collaterally. The IDF has lost at least 900 soldiers in the war that began that day, around 550 of them in Gaza since 8 October.

Saturday’s partial IDF pullback, Monday’s hostage–prisoner exchange, and the entry into the Strip of hundreds of trucks loaded with humanitarian aid (food, water, medical supplies, etc.), together constitute the implementation of the first stage of Trump’s peace plan, which ultimately provides for a gradual but full Israeli withdrawal from the Strip alongside the disarmament of Hamas and the administration and reconstruction of the devastated Strip by an international “Board of Peace,” chaired either by Trump himself or by former United Kingdom Prime Minister Tony Blair. This Board would supervise a “transitional” government, composed mainly of non-Hamas Palestinian technocrats, and an International Stabilisation Force (ISF) of soldiers and police, which would disarm Hamas and carry out the “demilitarisation” of the Strip, meaning the destruction of Hamas’s vast tunnel network and the supervision of the gradual IDF withdrawal back to the Israel–Gaza border. The plan allows for Israel, after the withdrawal, to maintain a 500–1,500-metre security “perimeter” on the Gaza side of the Israel–Gaza border for an indefinite period. In the long term, Point 19 of the Trump plan provides for the eventual takeover of the administration of the Strip by the “reformed” Palestinian Authority (PA) as a first step on the “pathway … to Palestinian statehood.”

Over the past two years, the IDF has managed to destroy only some 30–50 percent of Hamas’s tunnel network. Meanwhile, Hamas has recruited thousands of new fighters from among the very willing million or so youths in the Gaza Strip bent on revenge against Israel and on obtaining salaries from Hamas, which is bankrolled by Qatar and Iran.

Both Israel and Hamas have accepted the Trump plan, under strong pressure from America and its Muslim allies—but Hamas continues to assert that it will never disarm and will not agree to a non-Arab administration of the Strip, while the Netanyahu government remains committed to preventing the emergence of a Palestinian state, which it believes would pose an existential threat to Israel. Hence Netanyahu also opposes any PA involvement in the governance of Gaza.

These are the main obstacles to be overcome in the unfolding of the Trump plan, which was backed on Monday by an impressive gathering in the Egyptian city of Sharm El-Sheikh of international leaders, including the heads of the German, British, French, Indonesian, and Jordanian governments. At that brief get-together, which was also attended by Mahmoud Abbas, the “president” of the Ramallah-based PA, the leaders of Qatar, Egypt, and Turkey signed a declaration pledging their commitment to implementing the Trump plan. Their assistance, and that of the other attending states, would involve dispatching military and police forces to take control of the areas vacated by Israel and Hamas during and after the disarmament of the latter and the allocation of tens of billions of dollars to finance humanitarian aid for Gaza’s 2.3 million inhabitants and fund the reconstruction of the Strip’s infrastructure, public institutions, and housing, which observers believe will take at least five to ten years, given the extent of the territory’s devastation. The Strip’s hospitals, administrative institutions, schools, and universities have all been destroyed or severely damaged, and its water, electricity, and sewage networks are non-existent. It is noteworthy that the leaders of Saudi Arabia (Mohammed bin Salman al Saud), the United Arab Emirates (Mohamed bin Zayed al Nahyan) and the sultanate of Oman (Haitham bin Tarik) all absented themselves from the Sharm el-Sheikh summit. The first two are routinely named as the main financiers of Gaza’s reconstruction—and are strongly opposed to Hamas’s continued presence and rule in the Strip.

Over the coming weeks, American diplomats will hammer out the details of the establishment of the “Board of Peace,” the “transitional” administration, and the ISF with representatives of Western and Muslim governments. Meanwhile, Israel continues to occupy the uninhabited half of the Gaza Strip, while over the past few days Hamas forces have emerged from their underground tunnel hideaways and taken up conspicuous positions along main thoroughfares, at crossroads, and in the most imposing buildings in Gaza’s towns. Here and there, to assert their rule, they have publicly executed political opponents or those accused of collaboration with Israel and have tried to suppress anti-Hamas clan militias, which Israel established and armed in various parts of the Strip in recent months. Hamas has also, apparently, sent armed squads to feel out or challenge the new Israeli positions along the “yellow line” to which the IDF has withdrawn. Several Hamas gunmen have been shot dead in these attempts. Hamas has complained that these shootings represent Israeli violations of the ceasefire accord.

Israelis are wary of the key roles Trump has earmarked for Qatar, Egypt, and Turkey in the forthcoming implementation of the plan’s further stages. Qatar has been the Arab world’s main political and financial backer of Hamas—while, absurdly, also serving as a mediator in the Israeli–Hamas prisoner–hostage exchange and truce deals—and Islamist-governed Turkey, although it is a NATO member, has been a consistent supporter of Hamas and critic of the Jewish state. Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, recently compared Benjamin Netanyahu to Adolf Hitler and regularly charges Israel with committing “genocide” in Gaza—while denying the actual genocide that Turkey committed against its Christian minorities a century ago. Equally absurdly, Trump has repeatedly called the Islamist Erdoğan, who hates the West, a “friend.” Egypt has been at peace with Israel since signing a treaty with the Jewish state in 1979, but it is a Muslim-majority country where Hamas’s parent organisation, the Muslim Brotherhood, enjoys mass popular support—including, presumably, among the country’s soldiers and police. Trump expects Turkey and Egypt to provide much of the manpower for the ISF, while Qatar, alongside Saudi Arabia and the UAE, will supply the funds for the “transitional administration” and the reconstruction of Gaza. Most Israeli observers believe that Turkey and Qatar are interested in the revitalisation of Hamas and in its continued and ultimate control of the Gaza Strip.

Trump also looks to Indonesia, the Muslim world’s most populous country, to contribute manpower for the Strip’s administration and the ISF. Over the weekend, rumours abounded in Israel that Indonesia’s president Prabowo Subianto Djojohadikusumo would fly to Israel after the Sharm el-Sheikh meeting, and perhaps even establish diplomatic relations with the Jewish state. But nothing came of this. It is believed that Israel’s foreign intelligence agency, the Mossad, has maintained a close clandestine relationship with the Indonesian government over the past decade or two.

Egypt’s president, Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, has already announced that over the coming weeks he will be convening an international conference to plan Gaza’s reconstruction. He clearly hopes that Egypt and Egyptian companies will directly benefit from the massive prospective construction projects. Behind the scenes, there has been a roiling rivalry between Egypt and Qatar, both of whom are keen on projecting their influence over Gaza’s population and attaining the upper hand as the future go-between for Israel and Hamas. Over the past two years, Qatar has sidelined Egypt as the go-between—but Egypt, which controls the Rafah crossing into Gaza and Gaza’s southwestern frontier, seems to have a telling geopolitical advantage. Nonetheless, Qatar has emerged as the dominant mediator. The reasons for this are unclear and rumours abound. What is clear is that both before and after 7 October, a number of Netanyahu’s close aides received payments from Doha for beefing up Qatar’s image in both Israel and the West; and rumour has it that Netanyahu himself has enjoyed Qatari largesse over the years.

Netanyahu remains unpopular among Western European and Arab leaders. He was initially left out of the list of invitees to the Sharm el-Sheikh summit. At the last minute, Sisi invited him to attend, probably at Trump’s prompting. But in the end, Netanyahu preferred to stay home—perhaps because Erdoğan and possibly other attendees indicated that he was unwelcome, or because he did not want to be seen in the company of the Palestinian “president” Abbas, or because he feared negative internal Israeli political fallout if he attended.

The Trump plan, which the American president forced upon Netanyahu, has caused the Israeli premier a number of major headaches. First and foremost, it abruptly halted the IDF offensive in Gaza City, which Netanyahu sold to the Israeli public as the start of the final phase of the war, in which Hamas would be “utterly defeated.” Now it appears that—at least in the short term—Hamas will remain armed and in control of Gaza’s population. Before the Monday hostage–prisoner exchange, Netanyahu told the Israeli public in a TV appearance that Hamas would be disarmed, either “the easy way”—meaning voluntarily—or “the hard way,” meaning, apparently, that the IDF would resume its military campaign against the organisation.

But Trump has now killed any hope Netanyahu might have had of renewing the war (though in a televised appearance he assured the world that if Hamas did not disarm, the United States would disarm the organisation, he failed to explain how they could do so without boots on the ground). Washington provides Israel with political cover—preventing, for example, a UN Security Council vote to impose anti-Israel sanctions—and provides many of the munitions and spare parts the Jewish state requires to engage in full-scale war-making. Such munitions and spare parts would be crucial for Israel should its wars with Iran and Hezbollah be renewed. In June 2025, Israeli forces overpowered Iran and—with substantial American help—severely damaged or destroyed Iran’s main nuclear installations; and in October–November 2024, Israel crushed Hezbollah. Both Iran and Hezbollah have vowed revenge and a renewal of hostilities is not unlikely.

Both Trump’s peace plan and the Sharm El-Sheikh summit are causing Israel considerable worry though Israeli officials are not openly expressing it. Both augur an “internationalisation” of the Israel–Palestine conflict. Israel has always opposed such a development, fearing that the introduction of foreign—especially Muslim—forces into the area would ultimately aid the Palestinians, who are routinely perceived as the victims and underdogs of every conflict, whether or not they were the aggressors (as they were on 7 October). And the dangers of such internationalisation are not limited to Palestine. The injection of the UN force UNIFIL into southern Lebanon after 1978 helped Hezbollah by acting as a buffer that protected the Islamists from retaliatory attacks by Israel. In general, Israel has always regarded the United Nations itself, from 1948 onwards, as favouring the Arabs—whether through unwanted truce or ceasefire resolutions or political resolutions favourable to Israel’s enemies.

According to the Trump plan, armed international forces—whether Arab, Western, or both—are to enter the Gaza Strip and take control of areas the IDF vacates, technically preventing or at least limiting Israel’s ability to strike back if Hamas violates the terms of the ceasefire. Israelis are also sceptical of the ISF’s ability to disarm Hamas. Will Muslim ISF troops from Indonesia, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, or Egypt have the will or ability to fight Hamas fighters who resist being disarmed—especially since Hamas will naturally charge any troops that try to disarm them with acting as Israeli collaborators? Moreover, the Trump plan projects the establishment of a “pathway” to a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. For many Israelis, and certainly for Israel’s current right-wing government, this poses a serious diplomatic and political challenge.

The Trump plan and the ceasefire with Hamas have also caused a radical gear-shift in Israel’s internal politics. So long as the war was ongoing, Netanyahu had a somewhat logical pretext for resisting calls for new elections and for the establishment of a state or judicial commission of inquiry that would look at how and why the 7 October disaster occurred and who was to blame. Netanyahu has consistently denied all responsibility for the intelligence and operational failures of 7 October—when southern Israel was overrun by Hamas fighters armed only with Kalashnikovs and RPGs—and has routinely cast the blame on the country’s intelligence services and army. A commission of inquiry—headed by a Supreme Court justice, as required by statute—is likely to see things differently.

Since he assumed office in January 2023, Netanyahu has been focused on neutering Israel’s judiciary, especially the Supreme Court, through a so-called “judicial reform.” Most Israelis view the attempted “reform” as an effort to subvert the independence of the judiciary and establish authoritarian government. Thousands of Israelis poured into the streets in the months before 7 October in protest at the government’s move, creating a serious fissure in Israel’s social cohesion. Israel’s Islamist enemies, led by Hamas, interpreted what was happening as a sign of weakness and this helped prompt the 7 October attack and the follow-up attacks by Lebanon’s Hezbollah, Yemen’s Houthi militias, and Iran.

Netanyahu was particularly incensed by the country’s Supreme Court, which ruled against and blocked various government decisions. He has also gone after the country’s attorney-general, Gali Baharav-Mi’ara, who has ruled that various government measures are illegal. Netanyahu has so far failed to prod her into resigning or to remove her from office. In the latest slight—which was subsequently criticised by Israeli President Yitzhak Herzog—Knesset Speaker/Chairman Amir Ohana, obviously acting at Netanyahu’s behest, pointedly declined to invite Supreme Court president Yitzhak Amit and Baharav-Mi’ara to attend Trump’s Monday speech before the house.

Last month, Netanyahu succeeded in removing another Israeli gatekeeper, Ronen Bar, head of the Shin Bet security service, from office, replacing him with a Messianic right-wing settler and yes-man, General David Zini. Bar had been investigating the involvement of Netanyahu’s aides in the scandal known as Qatargate, in which they allegedly took Qatari payments for burnishing Qatar’s image in Israel and the West. Netanyahu appears to be worried that one or more of those aides might turn state’s evidence against him.

Netanyahu began to assail Israel’s judiciary in 2019 immediately after he was put on trial on multiple charges of corruption. His trial is now in its sixth year with no end in sight, in part due to delaying tactics by his lawyers. Neutralising the powers of the Supreme Court and the attorney-general might lead to an annulment of the trial. In his speech before the Knesset on Monday, just before he flew to Sharm el-Sheikh, Trump half-jokingly suggested that President Herzog, who was present in the chamber, grant Netanyahu a “pardon,” before he was even convicted. There were broad smiles on the faces of Netanyahu and his fellow Likud Knesset members at this suggestion.

Many Israelis fear that, with the war in Gaza at an end, Netanyahu is likely to restart the “judicial reform” in the hope that this will help rally his base of Sephardi-Mizrahi (eastern-origin) Jewish supporters, who, he claims, are victims of the “deep state” and suffer from under-representation in Israel’s core institutions, such as the Supreme Court. (Only one of the currently sitting twelve justices is of Sephardi origin, the rest being Ashkenazi (European-origin) Jews).

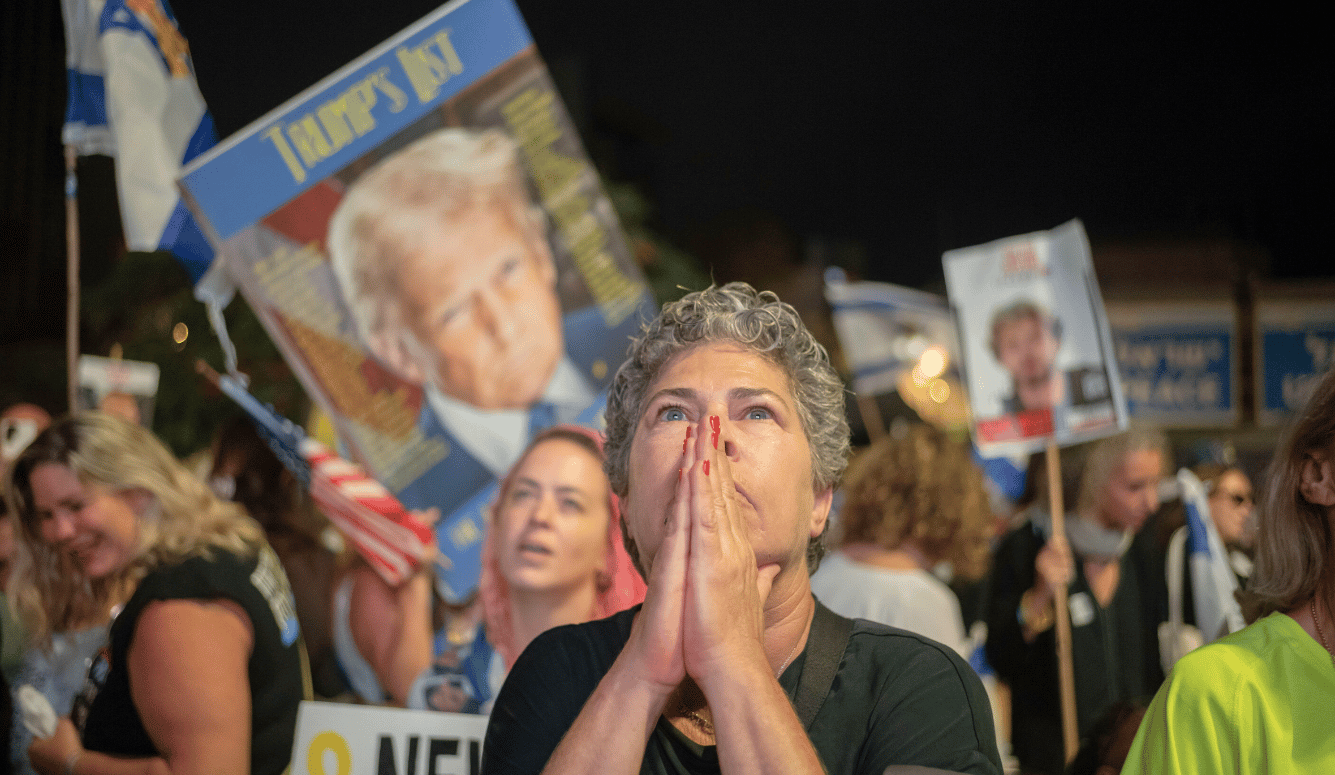

Last Saturday night, Israeli masses cheered Steve Witkoff, Trump’s Middle East envoy, in downtown Tel Aviv as he welcomed the impending hostage release. Whenever he mentioned Trump’s name, the crowd cheered; when he mentioned Netanyahu, there were loud boos and catcalls. Israeli opinion polls of this past year have consistently predicted that Netanyahu and his right-wing allies will lose in a forthcoming general election. If this happens, it could pave the way to the formation of a centrist government that might seriously consider Trump’s suggested “pathway” to a two-state resolution of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

That pathway is full of potholes, though. Tempers are still frayed, and there is no certainty that the conflict is about to end. Provocations by Hamas or actions by individual Islamist gunmen could well trigger Israeli reprisals that might unleash renewed full-scale warfare before the international community could even organise and establish a “transitional” administration and a multinational armed force that would act as a buffer between the enemies and disarm Hamas. Many Israelis believe that Israel should now apply the policy it has implemented vis-à-vis Hezbollah since the Israel-Hezbollah ceasefire agreement went into effect in November 2024—pre-emptive attacks on Hezbollah positions and assassinations of Hezbollah operatives whenever they are deemed a threat—in the Gaza Strip as well.

The coming months will doubtless be dominated by a tussle over the disarming of Hamas and the introduction of the temporary international governance of the Strip; the following year or two in regional and international diplomacy will likely focus on the problems of the West Bank and of Palestinian statehood.