Art and Culture

A Subterranean Celebration

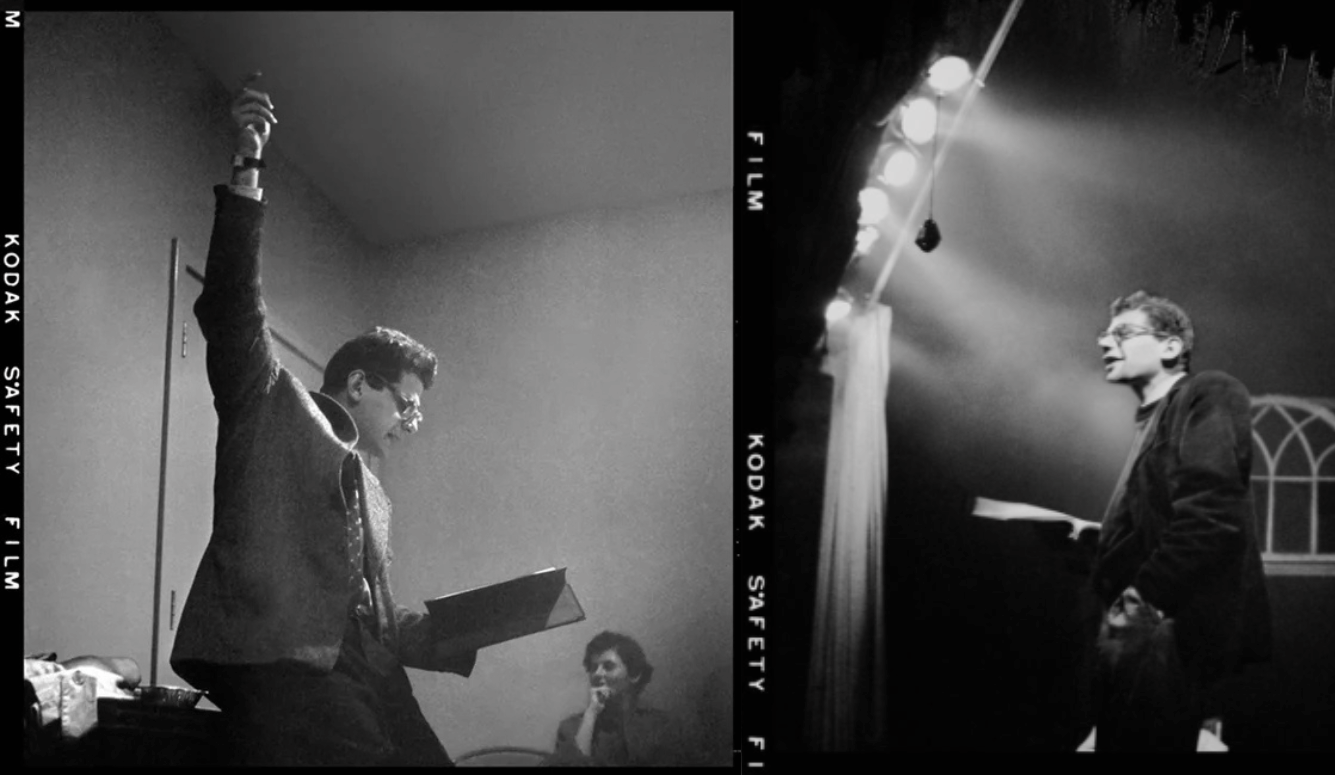

How the 6 Gallery reading in San Francisco on 7 October 1955 changed the counterculture.

On 7 October 1955, Allen Ginsberg gave the first public reading of “Howl” at the 6 Gallery in San Francisco. It was only his second poetry reading and he had little reason to feel it would be successful, yet a year later he was a minor celebrity and two years after that he and his Beat Generation friends were a national obsession—loved, loathed, imitated, and parodied. That reading started the San Francisco Renaissance, too, and helped to turn the Bay Area into a literary centre. It would not be long before the Beats spawned the beatniks, who arguably became the hippies.

It can be tempting to look back at events of great historical importance and feel that they were somehow inevitable, and yet that is not true of the 6 Gallery reading. In fact, its success was wildly improbable. The poets on stage that night were mostly unknown and untested. They read difficult work that should have had very limited appeal. Nor was the gallery itself a venue one would associate with era-defining moments. And while the city held some appeal as a place for the visual arts, it did not have a great literary history.

The 6 Gallery opened in October 1954 and was named for the fact that it had six founders: five young painter friends from near Los Angeles who had teamed up with one of their teachers at the California School of Fine Arts: a poet called Jack Spicer. In their final year of studies, they decided they wanted a place to display their work and Spicer encouraged them, suggesting that they expand the gallery’s function to include not just visual art but poetry. This was not as revolutionary as it perhaps sounds. Prior to the 6 Gallery, the building at 3119 Fillmore had been home to King Ubu, which was also an art gallery that one artist recalled was “primarily devoted to poetry reading.”

Both King Ubu and the 6 became known for their experimental art and their mixing of forms, but perhaps they both also functioned as social hubs for the city’s growing creative community. Exhibition openings tended to be wild nights where bohemian intellectuals drank and gossiped. The artists who showed their work in these places were unlikely to sell much, given that the visitors were often indigent artists like themselves, but they became places of tremendous creativity and helped form a new artistic centre in the city. A network of galleries soon opened around the intersection of Fillmore and Union, and nearby were a number of houses shared by painters, poets, and musicians. These homes were often a combination of accommodation, studio, and gallery.

At the time, San Francisco was beginning to gain a reputation as a place for visual artists and it was also known for its innovative jazz scene. Some of the world’s most renowned painters and photographers came to San Francisco to teach at the California School of Fine Arts, and almost all the jazz greats of the era could be found performing in the Fillmore District, a list that included Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, and Dizzy Gillespie. It was a cheap place to live and its position at the far end of the continent provided a sense of freedom. In terms of literature, however, the scene was not quite as established. Kenneth Rexroth had arrived in San Francisco in the late 1920s and had worked to position himself as a figurehead. His twice-monthly Friday night salons acted as the primary meeting place for poets, but there wasn’t much else. Robert Duncan and a few others had formed the so-called Berkeley Renaissance of the late 1940s, and there had been a few attempts to launch small magazines and poetry readings. But while the city’s painters gained a degree of national attention, its poets mostly just wrote for one another.

In the middle of 1954, Allen Ginsberg arrived in the Bay Area after a spell in the jungles of Mexico. He was immediately impressed by the city’s arts scene and made good friends there, but he felt that there were no truly talented poets. He befriended Rexroth and Duncan but was unimpressed by their writing or the salons and classes they ran. Thanks mostly to his lover Peter Orlovsky and the various friends he made, he decided to stay in the city for a while and found himself an apartment in North Beach, which was the city’s bohemian centre. It was here, in the middle of 1955, that he started writing “Howl.”