Art and Culture

Seasons in the Sun

Sex, money, murder, and the decline of Mike White’s wildly popular HBO series ‘The White Lotus.’

Editor’s note: The following essay assumes familiarity with all three seasons of The White Lotus. Spoilers are included throughout.

I.

When it premiered in 2021, 55-year-old Mike White’s award-winning HBO black-comedy/drama The White Lotus was a river that carried its audience briskly along with tight and inventive plotting, lively characters, acerbic dialogue, and a lean cluster of ensemble performances. But by season three, the series had swollen into a Nile delta of sluggish distributary rivulets, most of which went nowhere and were populated by deeply uninteresting people. The show retained some vehement defenders among fans and critics alike, but by the time it lumbered into its finale in April of this year, many of those who stayed the course agreed that the third season had been a big letdown.

Which is a shame, because the opening season of The White Lotus, set on the Hawaiian island of Maui, was a triumph of artistic creativity over severe topographic and political constraints. Chief among these were the draconian pandemic restrictions that prevailed during the fall of 2020, which effectively forced White to confine all six of the season’s fifty-odd-minute episodes to the plush Four Seasons resort on Maui’s Wailea Beach where the first season was shot. Because everyone involved was essentially a prisoner on Maui owing to the quarantines, White’s crew had to abandon the usual money-saving practice of using far-flung exterior locations for establishing shots while shooting interiors on studio sets back in Los Angeles. However, this created a palpable claustrophobia that ensured the fictional White Lotus Hotel would develop a reality of its own as another character in the series.

White’s narrative structure also imposed quasi-Aristotelian unities upon the action. A prologue informs us that someone has died at the show’s eponymous resort, although the identity of the departed and the circumstances of their passing are not revealed. The story then flashes back a week (a format that would be rigorously followed by each successive season) and we are introduced to eight super-rich, super-dysfunctional hotel guests—strangers with nothing in common besides the wealth that allows them to afford a week in the White Lotus—as they approach the luxury resort for their super-expensive holiday, blissfully unaware of the unspecified tragedy to come. White then has exactly seven days to resolve this absorbing mystery in reverse—who will become the story’s cadaver and how?

The largest party is the Mossbacher family:

- The father, Mark (Steve Zahn), is an over-sharer with an inferiority complex about the success of his ball-breaking wife.

- The mother, Nicole (Connie Britton), is a tech CFO who bosses her family around and spends the entire week plugged into her laptop, emailing and video-calling her company’s Chinese overlords.

- Spoilt leftist college-sophomore daughter Olivia (Sydney Sweeney) has been allowed to bring her chippy leftist best friend Paula (Brittany O’Grady) along, and the two girls spend their waking hours taking recreational drugs and lounging in poolside chairs judging everyone else with haughty disdain. (Their Gen-Z stares and nasal tonelessness are apparently borrowed from Red Scare podcasters Dasha Nekrasova and Anna Khachiyan.)

- Browbeaten younger son Quinn (Fred Hechinger) is a prisoner of his phone until the tide washes it out to sea when he spends a night on the beach.

Then there is honeymooning couple Shane (Jake Lacy), a vain and obnoxious real-estate bro, and his naive new bride Rachel (Alexandra Daddario), an anxious young internet journalist with a flailing career writing website listicles for peanuts. By the time the couple arrives at the White Lotus, it is evident that they are mismatched and that their marriage is already in trouble. Due to a booking glitch, the couple did not get the hotel’s coveted Pineapple Suite, and as Shane’s obsession with this error develops into a petty feud with the resort’s manager, it slowly dawns on Rachel that she ought to have done some homework on Shane’s personality before exchanging vows.

Finally, there is Tanya (Jennifer Coolidge), a formidably overweight and recently widowed dipsomaniac and world-class neurotic with a gnat-like attention span and the biggest pile of money of all. Upon arrival, Tanya immediately latches on to the White Lotus’s overworked spa manager and unofficial psychotherapist Belinda (Natasha Rothwell), who daydreams about opening her own spa (“a holistic experience,” she tells Tanya, replete with “spiritual therapies and body treatments” where “women of all economic backgrounds would benefit, not just rich women. Not that there’s anything wrong with rich women!”) Tanya fawns over Belinda and even offers to fund her business, before promptly vanishing when she is asked out by a wiry middle-aged man named Greg (Jon Gries).

White’s superlatively clever plotting thrusts all these unstable characters into conflict at once. Olivia and Paula delight in snubbing Tanya and the painfully ingratiating Rachel during poolside encounters. When Rachel approaches Nicole for career advice she is humiliated. Nicole’s frosty marriage to Mark is complicated by Mark’s conviction that he has testicular cancer. That turns out to be wrong, but he then learns that the alpha father he worshipped had a secret gay life and died from AIDS not cancer as he has always believed. He then decides to confess an old instance of infidelity to his son, which mortifies and enrages his wife. Paula, meanwhile, takes up with Kai (Kekuo Scott Kekumano), a Native Hawaiian youth working as a busboy at the hotel. When Kai tells her that the hotel’s construction robbed his family of their land and heritage, she gives him the code to the Mossbachers’ hotel-suite safe so that he can help himself to some reparative compensation.

And at the centre of this Celtic knot of plotting is Armond (Murray Bartlett), the resort’s gay manager, whose job is to cater to the whims and moods of the White Lotus guests and see to it that the help’s personal troubles never reach their privileged ears. Elegant, literate, and dressed just this side of tropical garishness (colourful linen suits, spectacular Hawaiian shirts), Armond is the most fascinating character in season one, and indeed in the entire White Lotus series. A recovering alcoholic, he somewhat resembles Basil Fawlty with a large moustache and volatile temperament that flips unpredictably between obsequious and spiteful. The stress caused by his feud with Shane seems to send him into a tailspin, releasing a mess of injured pride and repressed rage. When Tanya hands Paula’s bag to him after she finds it on the beach, he plunders Paula’s ketamine supply and turns his office into a den of iniquity with the help of two good-looking hotel underlings, in violation of every sexual-harassment ban ever devised. So complete is Armond’s loss of control that it is hardly a surprise when he turns out to be the corpse mentioned in the season prologue—fatally (but accidentally) stabbed after he lets himself into Shane’s room to defecate into his suitcase.

All of this is nearly pitch-perfect. In the hands of a less sensitive director, the extravagant dysfunction on display might have become a tiresome exercise in misanthropic cynicism or monochromatic class satire, but White treats his characters and their manifest shortcomings with great generosity. Quinn discovers meaning outside his phone with a group of local canoeists who take him under their collective wing; Mark rescues his marriage and wins the admiration of his jaded kids with an impulsive act of courage; Paula, who has gravely betrayed her host-family, learns her lesson (sort of) and receives Olivia’s forgiveness; Tanya finds companionship with Greg and the confidence to finally emancipate herself from the memory (and ashes) of her overbearing mother; Shane probably doesn’t deserve White’s mercy, but he is permitted forgiveness and an uneasy reconciliation with Rachel even so. Even the reptilian Armando is not without a rickety, touchingly defiant dignity, glimpsed during occasional moments of poignancy.

The drama unfolds before the lusciously photographed aquamarine breakers and opalescent skylines of Hawaii’s pristine beaches. Mike White lived in Hawaii for a while, and he knows its vegetation and ocean fauna. Perhaps the most mesmerising contribution to the series is Cristóbal Tapia de Veer’s haunting Emmy-winning score. A recurring feature of all three seasons in different arrangements, it is augmented in season one by ukelele-backed hapa haole standards and some traditional Hawaiian harmonising, exquisitely sung a capella by the Rose Ensemble, a Renaissance-polyphony chorus. Several of those songs are Christian hymns translated into Hawaiian by the New England missionaries who came to convert the natives during the early 19th century. A scene towards the end, in which Quinn and his canoe buddies paddle into a brilliant orange sunrise, while the Rose polyphonists sing “Crown Him with Many Crowns” in Hawaiian, is thrilling.

II.

The first season of The White Lotus was such a delight that it seemed to have nowhere to go but downhill—and so downhill it went, starting with season two, which ran for seven episodes instead of six during the fall of 2022. This time, White relocated the action to another fictional White Lotus property (actually another Four Seasons hotel) in Taormina on Sicily’s Ionian coast. It’s a gorgeous rocky setting and it made me want to book a plane ticket to Sicily, but it lacks the other-worldly exoticism of Hawaii. This is southern Italy, where the “spiritual” consists of a lurid Catholicism of candles, bleeding saints, and carnal peccadillos, and where you call for a priest when sin lands you on a stretcher. Released from COVID restrictions, White was now at liberty to move the action restlessly around some of Sicily’s most picturesque sites: a travelogue of town squares, piney rural roads, Greek ruins, Baroque churches, and frescoed palazzi. Unfortunately, he ruins it all with a preposterous plot and a bloated cast of insufficiently realised characters.

Among the more fleshed-out of these characters—by which I mean somewhat fleshed-out but not enough—are the Italian-American Di Grasso family: grandfather Bert (F. Murray Abraham), an old goat who pesters every female he sees; his middle-aged son Dom (Michael Imperioli), a Hollywood producer and serial adulterer whose wife has just left him; and grandson Albie, a pious scold who has just graduated from Stanford and knows nothing about the world but can’t resist sermonising at his father (I’m a Stanford grad myself, and I flinched with embarrassment every time). Three generations of sexual disaster, in other words.

The Di Grassos don’t have a word of Italian between them, but they are on a quest to reconnect with their Sicilian roots, including a visit to the towns where The Godfather’s Sicilian scenes were filmed. To Bert and Dom, The Godfather is a magisterial recreation of their forefathers’ immigrant experience. To Albie, who has sided with his mother in his parents’ marital spat, it’s material for a gender-studies lecture: “You’re nostalgic for the salad days of the patriarchy,” he informs them. “Men love The Godfather because they feel emasculated by modern society. It’s a fantasy about a time when they’d go out and solve all their problems with violence, and sleep with every woman, and then come home to their wife, who doesn’t ask them any questions and makes them pasta.” (Has Albie ever seen The Godfather?)

The second season suffers from the absence of Armond, who electrified every scene in which he appeared. The dramatic pivots around whom much of the action revolves this time around are Mia (Beatrice Grannò) and Lucia (Simona Tabasco), two frisky and cheerfully cynical young Sicilian prostitutes who make their livings off the hotel guests, even though they’re regularly chased off the premises by the no-nonsense manager, Valentina (Sabrina Impacciatore), who doesn’t want her ritzy domain turned into a high-class whorehouse. Lucia sleeps with both father and son Di Grasso, charging hefty sums to each (like the Carpenter in “The Walrus and the Carpenter,” Dom weeps over his serial infidelities while continuing to sleep with whatever he can get his hands on). She then runs an even more ambitious scam on the hapless Albie, who doesn’t know about his father’s dalliance and is under the impression that Lucia is in love with him.

Mia, for her part, sleeps her way into the job of hotel pianist and lounge singer, replacing the ageing Giuseppe (Federico Scribani Rossi), whom she accidentally sends to hospital when she gives him an unspecified narcotic instead of a Viagra tablet by mistake. This is all delightful opera buffa, but neither Mia nor Lucia has the depth that made Armond such a terrific villain as well as a figure of genuine pathos. Lucia, Catholic that she is, does experience a tearful moment of Mary Magdalene-style penitence, but then she’s breezily skipping off to her next swindle.

Mia and Lucia also figure in the puzzling marital imbroglios of another set of White Lotus-Taormina guests: Ethan (Will Sharpe) is a woolly-headed tech nerd who has just sold his startup for a small fortune; his lawyer-wife Harper (Aubrey Plaza) is a sourpuss in whom Ethan has lost sexual interest; Cameron (Theo James) was Ethan’s Yale roommate and now works as a finance-industry hustler whose main aim is get Ethan to park his millions in his ethically dubious investment firm; and Daphne (Meghann Fahy) is Cameron’s willowy but oddly liberated stay-at-home wife and mother to their two small children.

Daphne—all floaty dresses, perfectly blown-out hair, artfully contoured makeup, and perpetual smile—baffled me completely. Was she a tradwife? A Stepford Wife? A weird combination of the two? She and Cameron are huggy-poo all over each other, and they chase each other around their bedroom before falling into each other’s arms. Yet it turns out that Cameron is serially unfaithful (he immediately goes to work on Harper, who does not exactly run from his advances) and Daphne knows all about it. There is no reason for jealousy, Daphne tells Harper matter-of-factly—she refuses to be a victim, and in any case, the don’t-ask-don’t-tell arrangement with her husband allows her to enjoy sleeping with her trainer. So we are presented with an apparent paradox—the faithless couple has a strong and sexually fulfilling marriage, while the monogamous marriage is falling apart. Harper needs a trainer of her own, Daphne advises.

There are hints that Cameron does successfully seduce Harper on this vacation, and that Ethan sleeps with Daphne—but White deliberately keeps these scenes from us so we are never entirely sure. The Cameron-Harper-Ethan-Daphne quadrangle—or “CHED” to White Lotus aficionados—became the single most talked-about feature of the second season. In the media and on Substack, fans provided competing theories of what it all meant. Were Cameron and Daphne “rocking the status quo” of marital fidelity via their adventures, as one critic put it—or was Daphne’s cheery equanimity merely a front? Was Daphne’s blond and blue-eyed trainer the biological father of her blond and blue-eyed son, not the saturnine Cameron? The most persuasive theory came from Quillette’s Marilyn Simon, who argues that Cameron and Daphne were playing an elaborate game of playful deception (with lessons for Ethan and Harper) designed to heighten the erotic frisson between them: “Each knows that they’re playing a game. As the risks get riskier, the fun increases, as does a sense of intimacy born of playing this game together, just the two of them.”

My own interpretation was radically different—perhaps because I couldn’t get interested in any of these four people (although I rather liked Cameron for the sheer audacity of his moral trespassing). My theory of the case is that Cameron and Daphne get along like gangbusters because they’re partners in crime. Season two of The White Lotus is about, among other things, con artists and their grifts. Daphne is a manipulator assisting Cameron’s con on Ethan—they want Ethan’s money and Cameron has already ribbed him for not passing him insider tips, a felony that could have landed Ethan in Club Fed. Ethan, on the other hand, struck me as a dullard who killed every scene he appeared in (couldn’t he at least get a haircut?). And what exactly is his sex problem with Harper anyway? She’s a pill, yes, but she’s a perfectly attractive pill in her chipmunk fashion. Why doesn’t he just stuff a sock into her mouth and go at it instead of masturbating disconsolately to internet pornography when she’s not in the room? None of it made any psychological sense to me, and so I didn’t really believe the resolution when it finally arrived.

If the CHED sequences in Season 2 are puzzling, the murder mystery is entirely implausible. This time around, the corpse belongs to Tanya, who has returned with Greg, the boyfriend she met in season one. Tanya was an audience hit in the first season, thanks to Coolidge’s comedic talent (she has appeared in multiple Christopher Guest mockumentaries) and the swathes of chiffon she rocked in nearly every scene. So White clearly felt compelled to bring her back. But that meant he also had to bring back Greg, who is now Tanya’s husband and seems to have lost much of the affable sexual charisma he displayed in the first season.

When we first meet Greg in season one, he’s introduced as an outdoorsy career bureaucrat at the Bureau of Land Management (Tanya thinks the “BLM” stands for Black Lives Matter), and he seems like just the kind of cheery sensualist who could handle Tanya’s volcanic neuroses: a wiry little insect crawling all over her mountainous body. He certainly had me fooled. But in season two, White endows him with a radically different and sinister personality. Now revealed to be the manoeuverer of the longest of long cons, it seems he pursued and then married Tanya so that he could bump her off and get his hands on her vast fortune.

This involves a scheme of Rube Goldbergian contingencies, beginning with the meet-cute at her Maui hotel when he pretends he got his room number wrong. Then, after a year or so of (surely exhausting) marriage, he suggests a vacation for two in Sicily because that’s where his yacht-owning gay Brit-expat friend Quentin (Tom Hollander) lives—a man with whom he apparently had a Brokeback Mountain-style bromance when he was a cowboy in Colorado. Quentin can arrange for a mafioso drug dealer, Niccolò (Stefano Gianino), to take Tanya out on a dinghy, shoot her, and dump her body into the ocean after Greg has flown home as an alibi. What if Tanya says, “No, Greg, I’m paying for this trip, and I’d rather fly to Ibiza”? What if Niccolò demands to be paid immediately instead of waiting for Tanya’s will to go through probate?

The plan goes awry when Tanya brings along her twenty-something assistant Portia (Haley Lu Richardson), who begins a tentative courtship with Albie. That causes Quentin to employ his catamite, Jack (Leo Woodall), to distract and, if necessary, dispatch Portia. This loutish young man is repulsive in every physical and social way, but his blunt sexual forwardness turns Portia on (unlike Albie, who is so schooled in #MeToo that he has to ask Portia’s permission before giving her a kiss). It finally dawns on Tanya and Portia how much danger they are in, but this takes a while, and in the meantime there’s a detour into the Palermo opera house and a cocaine-fuelled orgy, neither of which has an obvious function in Quentin’s murder scheme. Events finally come to a head on Quentin’s yacht when Tanya seizes Niccolò’s gun and kills nearly everyone on board. Unfortunately, she then slips and smashes her skull as she tries to climb over the boat’s railing with a head full of wine and a pair of stilettos on her feet.

This is all completely ridiculous, but at least it’s entertaining. I had to chuckle when Tanya encased herself in her pink chiffon and hoisted herself onto a rented Vespa behind Greg so that she could fulfil her Monica Vitti fantasy. I also got a laugh when the Di Grassos finally pitched up at the home of their putative long-lost relatives in the countryside only to be chased off the curtilage by a trio of screeching Sicilian crones. The soundtrack, meanwhile, features some lovely Italian opera and vintage Italian pop over that craggy, sun-bleached Mediterranean scenery. So, a dip in quality from the first season, but by no means a dead loss.

III.

But by season three, Mike White seemed to have run out of good ideas. Clocking in at eight glacial episodes, the last of which was stretched to 83 minutes, the discursive script somehow managed to be both bloated and thin. The action jumped from the White Lotus resort on the Thai island of Ko Samui to various private yachts and homes, beach hangouts, and the bar-and-sex scene in Bangkok. Promising plotlines were forgotten, interesting characters were introduced and then discarded, Thai culture—Buddhist temples, festivals, street food, Muy Thai boxing, elaborately costumed Khon dancing—was laid on with a trowel, mostly, I suspect, to remind viewers of where they were. I began to wonder why the series was still called The White Lotus since so few of the characters seemed to want to spend any time there.

Season three’s weakest link is a trio of forty-ish female professionals, friends from childhood on a girls’ vacation: Jaclyn (Michelle Monaghan), a successful television actress and the best-preserved of the lot; Kate (Leslie Bibb), a well-fixed Texas wife; and Laurie (Carrie Coons), a corporate lawyer recently dumped by her husband and marinating in misery. The three drink like fish, party, and trade catty gossip whenever one of them is out of the room. But at their final dinner together, Laurie rambles a tipsy paean to... female friendship: “We, we started this life together. I mean we’re going through it apart but we’re still together, and I, I look at you guys, and it feels meaningful.” Please shut up, Laurie. Although good for an occasional laugh—watch the consternation on Laurie’s and Jaclyn’s faces when they find out that Kate voted for Donald Trump—all three should have been written out of the script before filming began.

Then there’s middle-aged Rick Hatchett (Walton Goggins), a seedy and impulsive career criminal who arrives with a devoted English girlfriend in tow named Chelsea (a leporine Aimee Lou Wood), who is half his age and has a head stuffed full of astrology. It’s never explained how this odd couple can afford the White Lotus, but we soon learn that Rick is not there on holiday. After persistent questions, he finally tells Chelsea that he has come to Thailand to avenge the death of his father by confronting the hotel’s aged co-owner, Jim Hollinger (Scott Glenn). I assumed he actually had some more lucrative illegal enterprise in mind that he didn’t want to tell Chelsea about, but no—he has actually come to the hotel with some inchoate notion of vengeance.

For some reason, White also decided to reintroduce Belinda, the spa manager from the Hawaii resort and season one’s least interesting character. Belinda is in Thailand for a work-related spa-management training session (doesn’t she already know how to manage a spa, since she’s been doing it for years?). Shortly after she arrives, she runs into—guess who?—Greg, who is now living under a new name near the resort with a young girlfriend named Chloe (Charlotte Le Bon), a former model who is as thin as Tanya was fat. Ah! What will we learn about the mysterious Greg, his character, and his motives this time around? Almost nothing as it turns out, since White gives him almost no lines or screen-time. We do discover that Greg has a cuckold fetish, but White does nothing with this information, and we don’t even see the scene in which it is first disclosed. Instead, we are made to watch Belinda fret about whether to blackmail Greg for the money Tanya promised her.

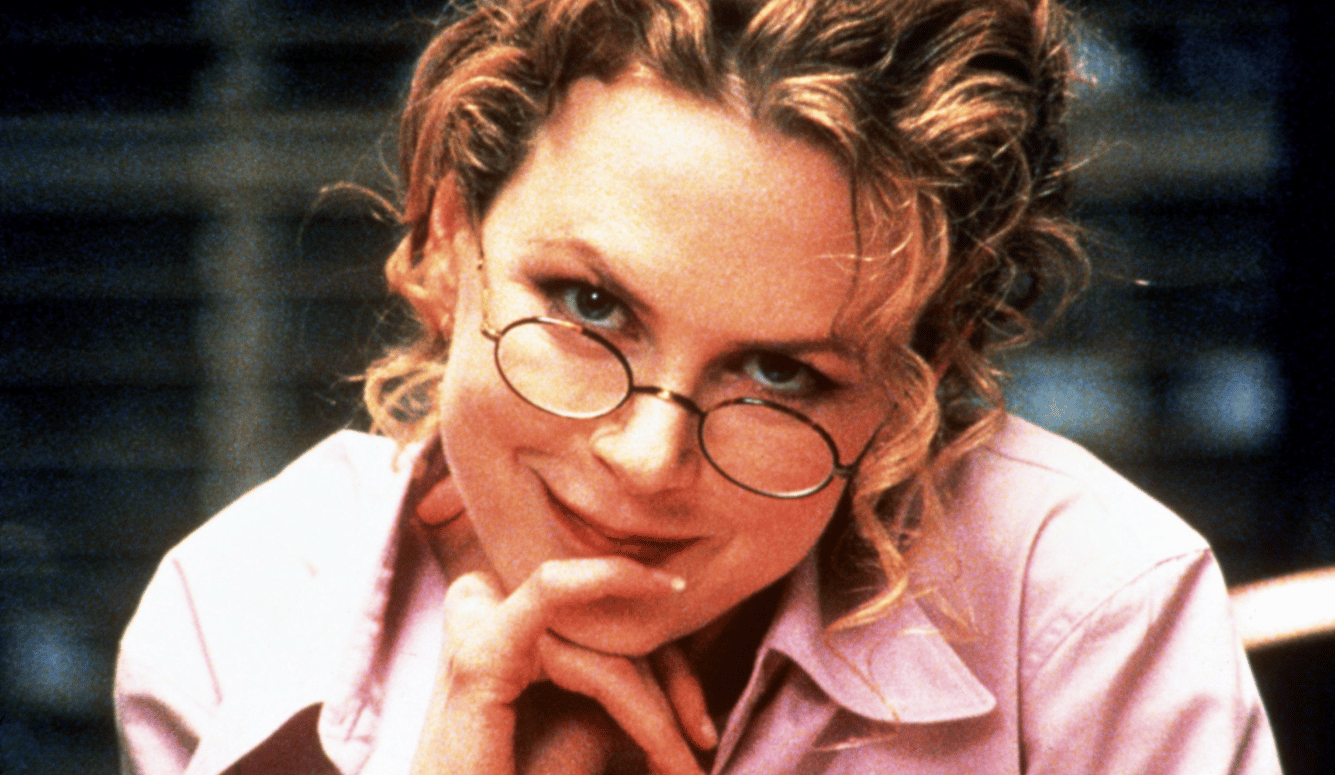

Finally, there are the new Mossbachers, the Ratliffs from Durham, North Carolina, all of whom are infected with the regional gentility and drawl but are as inert as a Southern funeral casserole. Upon arrival in the resort, the father, Timothy (Jason Isaacs), takes a phone call in which he is told that the FBI is investigating his business and that he will almost certainly face financial ruin, disgrace, and prison upon his return to the States. So he spends the vacation paralysed by anxiety, glumly contemplating various forms of suicide, and wondering if he should take his family with him. His cosseted wife, Victoria (a sadly underused Parker Posey), coasts along popping lorazepam.

Their elder son, Saxon (Patrick Schwarzenegger), works for his father and has only three interests: getting ahead, getting laid, and making protein shakes in his screeching blender (which is also a Chekhovian gun). Piper, the daughter (Sarah Catherine Hook), thinks she wants to enter the local Buddhist monastery, but changes her mind when she discovers that her cell isn’t air-conditioned and the monastery food isn’t organic. The younger son, high-school senior Lochlan (Sam Nivola), is a confused people-pleaser awaiting his first sexual experience. We spend a great deal of the season’s eight-plus hours with this vapid family and I never managed to care whether or not Lochlan lost his virginity or Piper ended up becoming a Buddhist nun. White tries to liven things up by staging an ecstasy-fuelled threesome for the two brothers and Chloe on Greg’s yacht, during which Lochlan masturbates Saxon. But since the scene never receives a satisfactory pay-off, I was left to wonder what it was there for.

The first season of The White Lotus aired at the height of DEI fever, and there was much carping from television critics about White’s relative lack of attention to “characters of colour” (the word “neocolonialism” was also bandied about). In season three, White seems to be trying to atone by creating a love-interest for Belinda, but this is not very convincing because Belinda simply isn’t sexy. He also sets up a Thai romance involving Gaitok (Tayme Thapthimthong), a security guard trying to balance being a good Buddhist against his job’s demand for aggression, and Mook, a lovely hotel “wellness expert” (Lalisa Manobal of the K-Pop group BlackPink). Unfortunately, neither Gaitok nor Mook has much of a personality, and the more exposed we are to Mook, the less beautiful she seems on the inside. She’s the kind of girl who lights up with a sunshine smile when she thinks Gaitok will receive a promotion for defending the hotel gift shop during a jewellery heist, but freezes when he confesses that he’s been reprimanded by his boss for letting the thieves get away instead. I wanted Gaitok to wake up and find a sweetheart who’s more in his league in the looks department and will appreciate him for the decent, hardworking soul that he is.

The most talked-about scene in season three—and the one most replayed on YouTube—is a monologue delivered in a Bangkok bar by Frank (Sam Rockwell), an old friend and likely former accomplice of Rick’s who has procured a gun for him to use in his vendetta against Jim. Frank reveals to Rick that he moved to Thailand because he had “a thing for Asian girls”:

And it got outta my head, what I really wanted was to be one of those Asian girls, getting fucked by me. ... Then I put on some lingerie and perfume, made myself look like one of those girls, and I thought I looked pretty hot. And then this guy came over and railed the shit outta me. ... And then, I realised, I gotta—I gotta stop, the drugs, the girls, the you know, trying to be a girl. I got into Buddhism, which is all about, you know, spirit versus form, detaching from self, getting off the never-ending carousel of lust and suffering.

It’s a virtuoso performance by Rockwell, and White deserves credit for bravely confronting the issue of autogynephilia, a heterosexual-male fetish for imagining oneself as female and dressing in women’s clothes. Autogynephilia was first identified by University of Toronto psychologist Ray Blanchard during the 1980s as not uncommon among men seeking midlife gender transitions. But transgender activists have made the condition (and Blanchard himself) taboo—“a widely discredited pseudoscientific theory,” according to Out magazine—because it counters the LGTBQ dogma that transgenderism is a matter of innate gender identity. All of which is very interesting, but Frank’s confession, like so much else about season three, turns out to have nothing whatsoever to do with any of the plot-lines, exiguous though they may be.

Finally, things wind up. Laurie gets laid at last. Belinda extorts US$5 million from Greg with the help of her MBA son (Nicholas Duvernay) in return for leaving Thailand for good; Timothy resolves to kill himself and his entire family with poisoned piña coladas made in Saxon’s blender. He backs out at the last minute but almost kills Lochlan anyway, who makes himself a protein shake the following morning without rinsing out the blender first. Lochlan collapses but returns to life just in time to join the family on their departure to the grim reality that Timothy will soon reveal.

Rick confronts Jim in Bangkok but can’t bring himself to kill him. However, when he encounters Jim back at the White Lotus, Jim taunts him and calls Rick’s late mother a “slut.” So Rick shoots him dead only to discover, in a twist so obvious that it can be seen from space, that Jim was his father all along. Chelsea is then caught in the crossfire between Rick and Jim’s bodyguards, and after Rick scoops her body into his arms and staggers away like Lear carrying Cordelia, he is shot in the back by Gaitok—an act of cowardice that finally wins him Moko’s hand and the bodyguard job he’s been after. I must admit I shed a tear at this point. Chelsea, guileless and loyal to a lover who could not take care of her, was the only character in season three for whom I developed any feelings of affection at all. Well, and Rick, because he genuinely loved Chelsea and seemed so helpless in the face of passions he could not control.

Blame the end of COVID restrictions, or blame Mike White’s swollen head after five years of awards and adulation, but the overcooked wreck of season three is a far cry from the tightly structured narrative edifice of season one.

IV.

One of White’s problems—no doubt a function of being in charge of everything in these productions—is a certain exhibitionist self-indulgence; a propensity for giving us too much of a good thing (and also too much of bad things). This was evident, just around the edges, even in the series’ first season. For example, when we learn about Mark’s fear that he has testicular cancer, do we really have to see his enlarged scrotum? And why is prim and shy Rachel wandering around in plunging necklines and skimpy bikini tops that seem inappropriate for her, especially when Sydney Sweeney’s famously ample bustline is more modestly costumed? Perhaps White believed that the only way he could get across the outrageousness of Armond’s office sexual misbehaviour was to display it graphically (I never thought I would witness a rim job on my TV screen). The same can be said of Armond defecating into Shane’s suitcase (although the faeces are, mercifully, CGI). Perhaps this intolerance for scatology makes me an outlier, but I found the graphic detail unnecessary. After all, writers and directors on stage and screen have managed for millennia to convey depravity and decadence without delving quite so far into the visually granular.

There was more of the same in season two: Jack and Quentin’s sodomy leaves little to the imagination, as does a scene in which Cameron displays his extraordinary male endowment to Harper (it’s a prosthetic, as was Steve Zahn’s in season one). By the time we get to season three, it’s a veritable sausage-fest. Timothy accidentally flashes his family (“Dad!”) when he slumps onto a barstool by the kitchenette and his bathrobe slides open. There’s more male full-frontal nudity during a jacuzzi scene, and Saxon shows off everything he has as he undresses for bed in front of Lochlan. Television and the movies seem to have switched places in terms of sexual decorum since the 1970s, when Hollywood movies experimented with full frontal nudity but television was pitched to families with children watching in their living rooms. Now, it’s television that regularly goes R-rated, while most moviemakers, cowed by the Harvey Weinstein scandals and #MeToo, have come close to reintroducing the Hays Code. Or it may simply be that White, who is gay, can’t resist indulging his interest in naked men and their genitalia. There is plenty of sex involving women in The White Lotus, but the cameras are more discreet, and we never glimpse female pudenda.

Such extravagances aren’t limited to sex. In season two, Harper wanders through the medieval piazza in Noto and is ogled by leering male locals. What is this scene supposed to signify? The answer seems to be: Mike White’s encyclopaedic knowledge of obscure moments in cinematic history. In Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura (1960), Monica Vitti (again!) walks through the very same piazza and endures the same treatment from the men loitering there. Movie-trivia Easter-egg hunts like these may be fun for film buffs (there are many similarly pointless allusive tidbits on display over the course of the series), but they risk making the enterprise look like a vanity project, and I wish White would drop them when they serve no narrative purpose. I’m an Aries like Chelsea, and as Chelsea says, “I need everything out in the open.”

These irritants are a pity, because season one of The White Lotus demonstrated that White has enormous talent in all the areas that make a great director: pacing, cutting, character-creation, realising emotional effects through colour and sound. He is also a master of comedy. In season three, while Rick is in Jim’s Bangkok study having his life-or-death confrontation, Frank watches his wife’s old movies with her in their living room. It’s a tiny scene, a sliver of a few seconds, but it’s so funny and inventive that it almost makes the sludge of the rest of season three worth wading through. (Why does Rockwell—he’s a snake-charmer—have only a cameo role in season three? Why isn’t he the star, the Armond-like glue that holds everything together?)

In a March 2025 essay for the Atlantic titled “The White Lotus Is the First Great Post-‘Woke’ Piece of Art,” Helen Lewis writes: “The White Lotus repudiates the ‘peak woke’ era of the late 2010s, which yielded safe, self-congratulatory, and didactic art, obsessed with identity and language, that taught pat moral lessons in an eat-your-greens tone.” She’s right. On the LBGTQ front alone, The White Lotus treats autogynephilia as a genuine phenomenon, makes sly fun of Brokeback Mountain, and portrays nearly all of its gay characters as villains instead of the haloed saints and homophobia victims we’ve been fed by Hollywood for decades. That means Quentin and his passel of homicidal conspirators, and also Armond in all his dark complexity.

White is also spot-on in his pointillist renderings of the preening self-satisfaction of an American elite class so certain of its moral, intellectual, and political superiority: Jaclyn’s and Laurie’s Trump-horror, Albie’s sanctimonious pieties, Paula lounging poolside and being served drinks by the locals while she reads The Wretched of the Earth. These are people whose idea of the “spiritual” means a really good back rub, plus a smattering of non-Western religion—any non-Western religion, as long as it doesn’t interfere with their creature comforts and pet vices.

And underneath the black comedy and social satire, serious themes are being explored to which the narratives in all three seasons repeatedly return: legal and illegal drugs, for example, without which hardly any of the vast number of characters can get through a day or a party. And White is fascinated by family dynamics with their inter-generational tensions and sibling rivalries. The Di Grassos alone are a kind of dynastic study in familial origins and Italian-American immigrants’ successive alienation from familial roots and traditions. None of the three generations of Di Grasso men we meet at the White Lotus-Taormina has any understanding of the other two—and all three are completely cut off, linguistically and culturally, from their Sicilian progenitors and their own Sicilian cousins. This is fascinating stuff, because it embodies the same underlying theme that runs through the Godfather movies that Stanford-educated Albie looks down his nose upon.

And then there is the constant drumbeat of money: everything at a White Lotus resort—every last massage, every tropical cocktail, every “wellness” experience, every pristine beach-scape, and almost every moment of sexual pleasure—costs wealth that some characters enjoy and others desperately covet. Where one of these items doesn’t exact a transactional payment, it exacts a moral cost, as we see with Belinda, with Paula, and with Gaitok. Heists and cons, embezzlement and blackmail, prostitution literal and figurative, marrying and killing for money—the cash register is always ringing in the background.

What White is most interested in exploring, however, is the dynamics of love and sexual attraction between men and women. This is startling for a gay man. The gay friends I’ve had over the years have all shared a complete inability to understand heterosexual men’s desire for women. To them, women were either fabulous exotics like Tanya (or Sally Bowles in Cabaret), who might share their interest in, say, opera or art or decoration; or else they were service animals of some sort, of which gestational surrogates are the paradigmatic example. They seemed to honestly believe that heterosexual men married for strictly practical reasons: money, offspring, convenience, companionship.

Mike White is an exception. Perhaps it’s his experiences and his observations as an actor and writer; perhaps it’s all book-learning in evolutionary psychology and related fields. But he understands completely that, contrary to the feminist catechism, what moves women are men’s manifestations of dominance, with themselves as the object. (It’s why the otherwise repellent Jack enjoys immediate success with Portia.) When Mark finally asserts his masculinity in season one by tackling the burglar menacing his wife, I experienced my own thrill of excitement: he was—at last—her protector, and her sexual frigidity thaws in an instant. Later that night, they make passionate love for the first time in an age. His children are in awe. “You looked like a badass!” Quinn enthuses. “You saved Mom!” Olivia marvels. Mark may never earn as much money as Nicole, but he can lead his family with authority and dignity now that he’s established himself as the patriarch.

I think that something similar occurs when Ethan slugs Cameron in a fit of jealousy and then finally makes love to Harper, much to her delight. Contrast those two to the hapless Gaitok in season three; his situation is superficially similar to Mark’s. But when he shoots an unarmed man in the back, he doesn’t protect anyone; it’s an act of supplication aimed at pleasing a woman who is likely implacable anyway. Gaitok is in for a lifetime of misery with Mook—that is, assuming Mook, who is pretty enough to have her pick of suitors, stays with him at all. It’s all extraordinarily primitive, this assertion of profound sex differences, and it’s certainly politically incorrect. White has displayed admirable courage by violating the unwritten laws of feminism, and admirable truth to both art and psychological reality.

And then there is the matter of religion. White is clearly impatient with the affluent Westerners who view Eastern religion as a kind of self-care retreat and are shocked to discover that Buddhism as it is actually practised in the East demands austerity and sexual continence. But his interest goes deeper than that. White studied Buddhism for a while during a writer-burnout crisis, and he treats the religion with utmost seriousness. The Buddhist abbot at Piper’s monastery (Suthichai Yoon) has harsh words for Timothy as he contemplates suicide: “Everyone runs from pain towards the pleasure, but when they get there, only to find more pain. You cannot outrun pain.” Timothy ought to have reflected on those words but he doesn’t. And Rick, who really could have benefited from their wisdom, never hears them. Practising Buddhists have complained that White doesn’t get Buddhism quite right, but at least he doesn’t turn it into Asian-enlightenment “mindfulness” woo.

It is Christianity, however, that receives the most intriguing treatment in The White Lotus. When I heard those Christian hymns sung in Hawaiian during season one, I was bemused. Was this sincere religious expression or irony? (The background music for Armond’s final degradation is Bach’s “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring.”) White was raised evangelical. His father, Mel White, was a longtime speechwriter for Jerry Falwell, until he came out in midlife as gay (the parallels to Mark’s father in season one are obvious). I expected, then, the usual hostility toward Christianity of ex-evangelicals—and Victoria in season three is indeed a figure of fun; she prays to Jesus to save Piper from joining the “cult” with its “guru” at the Buddhist monastery.

But then, another Christian hymn, the 15th-century Christmas carol “Lo, How a Rose E’er Blooming,” with its theme of Christ’s birth as a flower growing in the cold of winter, figures in season three—twice. Timothy sings it to himself as he thinks about putting a gun to his head. Then it reappears in gorgeous choral harmony in the background as we see a montage of those who have managed to escape death: Timothy and his family, Belinda and her son, Frank doing Buddhist penance for his sins. White is preoccupied by redemption and forgiveness, which are both Christian motifs. He bestows redemptive second chances even upon those characters who haven’t really earned it: Shane in season one, Dom in season two, and Timothy in season three. Season three would have packed a harder ironic punch had Lochlan died and left his father to pay in full for indulging in self-pity and fooling around with mass murder. But the grace of God is free, and freely given, unlike the amenities at White Lotus resorts. Portia experiences some of it in season two when Jack, touched by her naivety and her loyalty to Tanya, drives her to the airport instead of murdering her as he was no doubt instructed.

All that said, I am not looking forward to season four of The White Lotus, which is scheduled to begin filming in France in 2026. Will there be even more episodes, characters, quirks, and corpses than in the record-setting third season? Should White have spared Armond, his most fully realised character, and had him preside over an ever-changing round of guests in Maui, his most fully realised setting? Or should he have quit while he was ahead? Fawlty Towers, for example, ran for a mere two widely separated seasons of six episodes apiece, preserving its reputation as one of the highest quality sitcoms ever made.

Still, there is something infectious about White’s sheer prodigiousness in creating characters and situations for them to get into. During all three seasons of The White Lotus, avid viewers tracked and obsessively analysed every word spoken, every arcane allusion inserted, every costume worn (was Victoria’s one-shouldered orange dress a riff on Buddhist monastic garb?). They were infatuated, like Dickens fans awaiting the next serialised instalment of his latest novel. Compare that level of engagement to that provided by the anaemic movies recently airing in movie houses: 28 Years Later, Eddington. Mike White has been giving his audiences what they crave: characters who become real people for them, plots that keep them guessing, comedy, and tragedy. And that might be enough.