Politics

Dangerous Games

In its quest to exploit Myanmar for diverse ends, the Chinese Communist Party keeps underestimating the state’s volatility.

Twin pipelines run from Ramree Island and Maday Island on the western Burmese coast. The first carries gas from offshore fields in the Andaman Sea; the second carries shipments of crude oil from the Middle East and Africa. The pipes crawl east for hundreds of miles across northern Myanmar, eventually crossing the border and finding their respective termini in the Chinese cities of Guigang and Kunming. This is a good investment for China: the oil pipeline alone cuts transport distances by 1,200 km. But it’s an ever-present mockery of the Burmese population, two-thirds of which has no access to reliable electricity. Four off-take stations allow Myanmar to use just twenty percent of the gas.

The pipelines are part of the China–Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), a multifaceted infrastructure project that Chinese President Xi Jinping has called the “priority among priorities” for his Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Indeed, the CCP sometimes gives the impression that this is how it views the entire state of Myanmar—as one long economic corridor for Party purposes; an extended anteroom to China itself. But the true value and purpose of this infrastructure will only emerge in the great crises of the future. China ships eighty percent of its crude through the Strait of Malacca, which links the Indian Ocean to the Pacific. In the event of war with the United States over Taiwan, that strait is likely to be compromised. Alternative energy routes would suddenly become vital to the Chinese economy. And so, for now, those precious pipelines must be kept pristine.

That is not an easy job, since Myanmar is ablaze with civil war. A patchwork of militias and ethnic rebel armies battle the Tatmadaw (armed forces representing a junta that stole power in February 2021), while also fighting against each other. Beijing has sold the Tatmadaw more than US$250 million in arms, to minimal effect. Even “highly simplified” maps of Myanmar’s contested regions show a state fractured to the point of incomprehensibility—a piece of smashed glass on the world stage resembling the last stages of the Holy Roman Empire more than any modern nation-state. And the picture is shifting all the time.

Almost three million citizens have been displaced since the coup. There are fears of famine and starvation. Many people hide in the jungle, where they rely on Elon Musk’s Starlink. Beijing has begun flying mercenaries into the country, but not to fight alongside any of the combatants. Their job is very clear: protection of CCP assets.

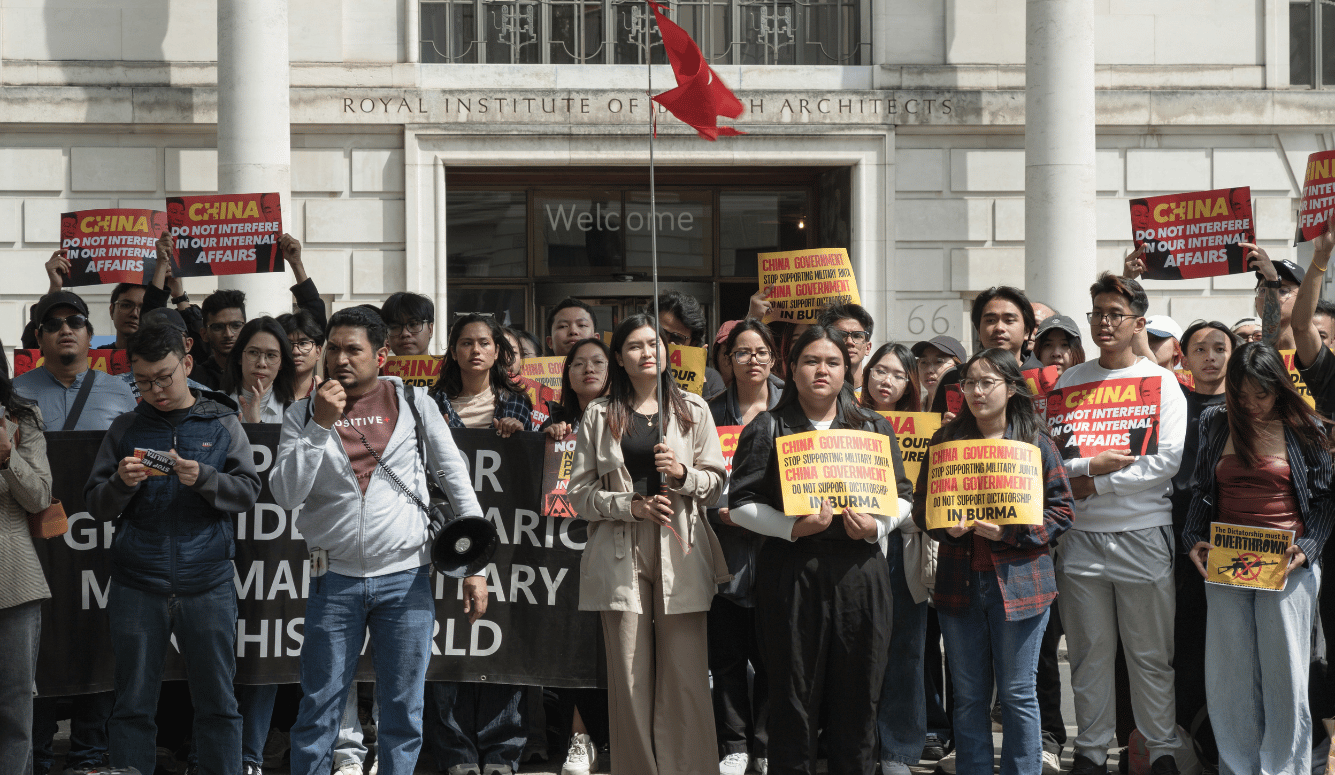

Myanmar’s resistance is struggling to hold back a tide of public anger at CCP support for the coup. Netizens have said they will “blow up” the pipes, which represent China, and there have been several guerrilla attempts to carry out that threat. After Beijing gave instructions to tighten pipeline security, the junta fell in line, no doubt worried about the flow of munitions arriving from various Chinese proxies. In some places, the pipes are now thought to be so well-protected that civilians will even choose to shelter in their shadow, hiding from the country’s endemic violence. Unfortunately for those civilians, Tatmadaw protection involves the planting of landmines in the woods near pipeline control centres. Farmers have stepped on mines while searching for their missing goats and buffalo.