Politics

Working for the Company

The modern CIA is everything its enemies and friends say it is—by turns heroic, villainous, duplicitous, servile, and frequently ineffective.

A review of The Mission: The CIA in the 21st Century by Tim Weiner, 464 pages, William Collins (July 2025)

The end of the Cold War brought confusion and even desperation to the CIA. Unlike the Soviet Union, which the agency had been designed to fight, the new enemy it faced—transnational terrorism—was a diffuse threat that employed cyber technology as well as conventional and suicidal weapons in its attacks on democracy. Adjusting to the new geopolitical reality was difficult, and as Tim Weiner shows in this excellent book, the modern CIA that emerged in the 21st century is everything its enemies and its friends say it is—by turns heroic, villainous, duplicitous, servile, and frequently ineffective.

Since the CIA reports to the US president, Weiner is particularly horrified by the rise of a “dictatorial” personality like Donald Trump with an elastic understanding of truth and reality:

Only good intelligence can prevent a surprise attack, a fatal miscalculation, a futile war. But even the best intelligence will not sway a leader who will not heed it. Among the CIA’s greatest challenges in the days to come will be the man in the White House, an authoritarian leader who presents the clearest danger to the national security of the United States since the century began.

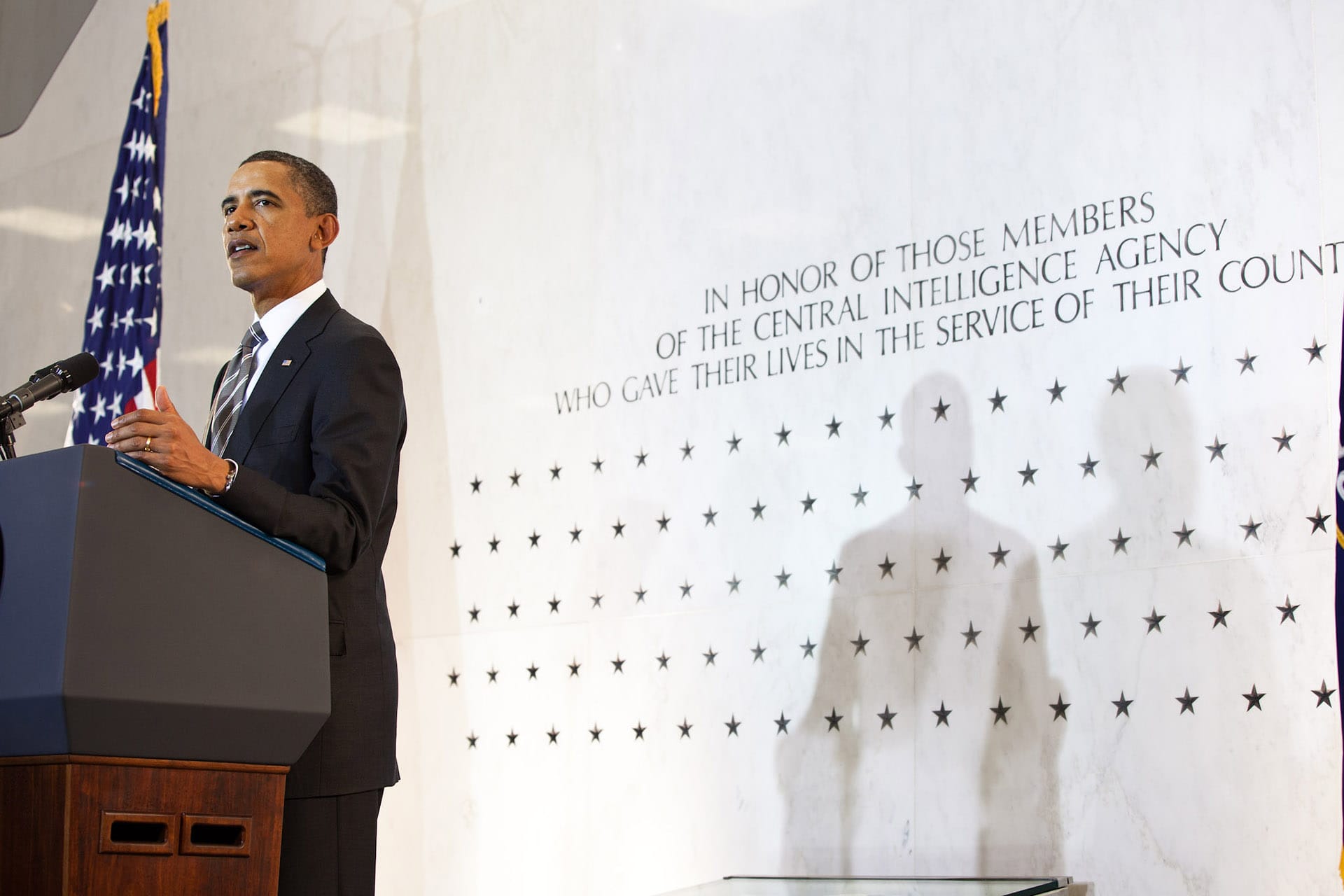

Weiner leads us through the administrations of the 21st century’s four presidents—George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Trump, and Joe Biden. Obama comes out of his review best because he was, in Weiner’s estimation, a man whose thinking could “be swayed by good intelligence.”

The Bush administration was not helped by the “false intelligence” that it received from the CIA about 9/11 and Iraqi WMD (the agency didn’t even devote the mandatory six months to develop intelligence assets in Iraq). But Weiner argues that good information would probably not have changed the administration’s course anyway once it developed its obsession with changing the regime in Iraq.

Then-secretary of state Colin Powell told Bush that any new government installed by the US would shatter like “crystal glass. There will be no government. There will be civil disorder.” But Powell and others who warned the president that an invasion would be calamitous were simply ignored. Weiner believes the failure to plan for a post-invasion insurgency doomed America’s reconstruction and democracy-building project: “The strategic incoherence of the White House now reached a high-water mark. … As a direct consequence, the United States would have no strategy for counter-insurgency for three years.”

Powell was also “devastated” to learn there were people within the CIA itself who doubted agency director George Tenet’s confident assurance that the Iraqi WMD intelligence was a “slam-dunk.” “There were some people in the intelligence community,” he said, “who knew at that time that some of these sources were not good, and shouldn’t be relied upon, and they didn’t speak up.” Had they done so, they would have had to contend with what Weiner calls “the dark side of the White House” as embodied by then-vice president Dick Cheney. Convinced there were WMDs in Iraq, Cheney “constructed his own shadow National Security Council.” “We had two [National Security Councils],” Powell notes. “One that belonged to [secretary of state] Condi Rice and the other one belonged to the Vice President.” Using unverifiable intelligence, Cheney “inserted himself totally into the information flow as if he were the chief of staff and into the foreign policy flow. That caused a great deal of confusion. The President tolerated this.”