Politics

The Phantom Enemy of the Culture War

The postwar decline of the West was not sabotage, it was conviction slowly unwound in the face of horror.

In 1984, a man in a grey suit sat across from a talk-show host and calmly declared that the United States was already at war. It was not a war of bombs or bullets, but of ideas. Yuri Bezmenov, a former KGB propagandist turned defector, warned that the West’s greatest danger was not invasion but decay, a slow process of ideological subversion. Marxist-Leninist doctrine, he claimed, had crept into American schools, media, and public life, leaving society hollow and uncertain.

Bezmenov’s four-stage model—demoralisation, destabilisation, crisis, and normalisation—offered a neat narrative of collapse. In his telling, radical ideas had been planted deliberately, eroding Western confidence and preparing the ground for revolution without violence. That interview was once obscure, but its claims are now invoked by those alarmed by identity politics, institutional distrust, and the fading of shared norms. His words feel prophetic.

But something in Bezmenov’s account does not fit. He was describing a West already in motion, shaped by forces far older and deeper than Soviet intrigue. He identified the symptoms but misdiagnosed their origin. His model assumed a conspiracy. But what if the rot was homegrown? What if the erosion of truth and cultural confidence came not from infiltration but from grief? What if the unravelling began not in Moscow but in the trenches of the Somme, in the ruins of Verdun, and in the silence that followed? To understand why Western institutions lost faith in themselves, we must look beyond propaganda to the wreckage left by two world wars.

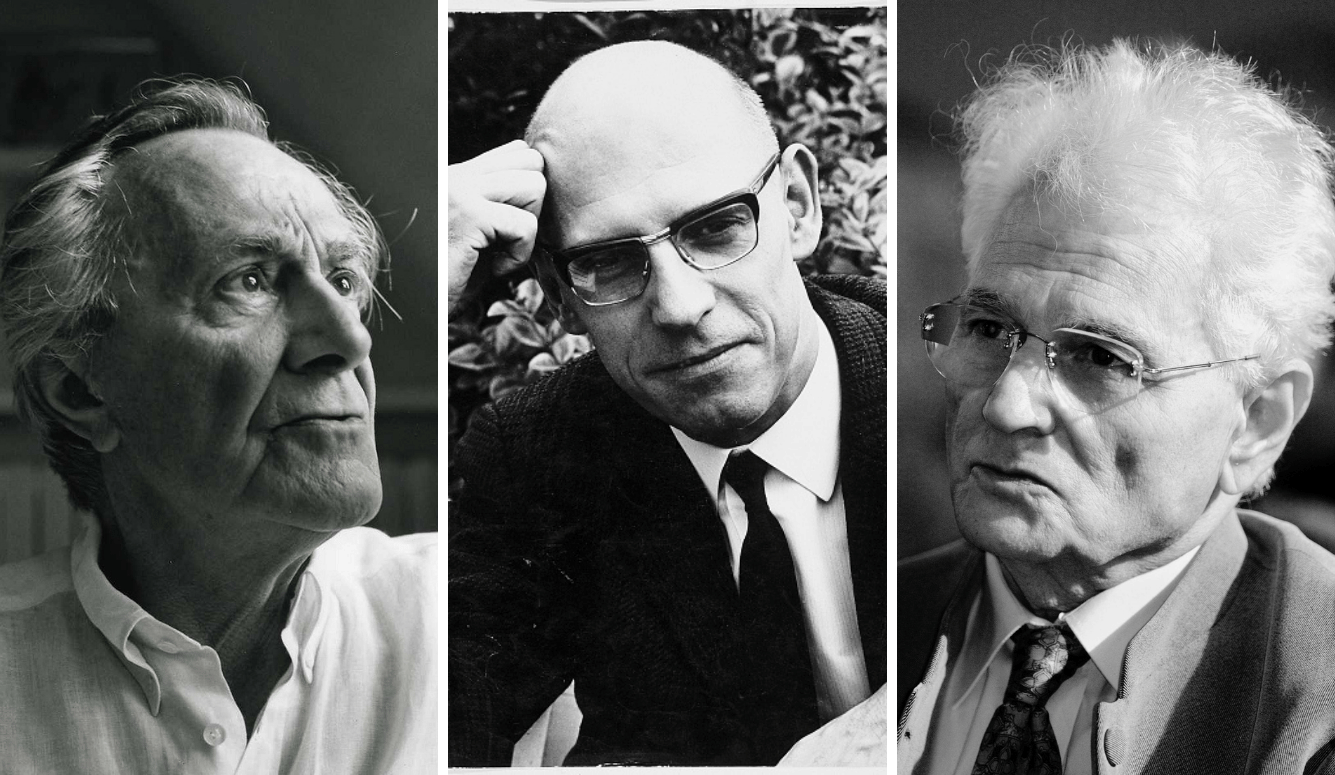

The thinkers who emerged from that wreckage did not carry manifestos. They carried questions: about truth, about power, about coherence in the aftermath of catastrophe. This is not a story of sabotage. It is a story of a collapse so profound that it reshaped the West’s intellectual architecture. Postmodernism, not Marxism, redirected Western culture, and we mistook mourning for malice.