Art and Culture

The Geopolitical Thriller: A Right-Wing Genre

Other plots may attract both right and left-wing authors, but successful geopolitical thrillers are always informed by a conservative view of the world.

Frederick Forsyth once came to speak at my university and with a hundred or so other students, I trooped along to the Union to hear the great man, hoping for some tips on how to write a thriller. He did not oblige. Instead, the “how-to” guide he decided to share was not about crafting a bestseller, but rescuing Britain from the morass into which he thought it had fallen. Bringing back hanging and National Service ranked high on the list.

For Forsyth was unashamedly a man of the Right: an early promoter of Brexit and a proud supporter of Margaret Thatcher, who appears in some of his novels. He was not alone in this. Across the Atlantic, his more verbose peer Tom Clancy was an unabashed Reaganite who dedicated one of his novels to “The Man Who Won the War.” Likewise, Brad Thor, author of a series featuring former Navy Seal Scot Harvath, describes himself as a “conservatarian,” while the late Vince Flynn, creator of the Mitch Rapp books, recalled being inspired to write after reading a book decrying government waste. Geopolitical spy thriller writers tend to be right-wing writers.

John Le Carré may seem like an obvious counterexample. The author of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy was increasingly open about his left-wing politics in his later years, telling the playwright David Hare that he wanted to see Tony Blair “punished” for continuing Margaret Thatcher’s legacy of privatisation and making regular expressions of his anti-Americanism. So frequent were these that obituarists have speculated on their root cause—perhaps resentment that the US had taken over the Empire his generation of Englishmen had been educated to run.

Le Carré, however, wrote in a subtly different genre from the other authors I’ve mentioned: the spy novel, not the thriller. Espionage was the lens through which he examined the human condition, focusing on the universality of corruption and, particularly, the impact of deception on those who practise it. And he had literary aims. Forsyth, Clancy et al. had no such pretensions—though that is not to say that their works are mere entertainments and nothing more. A clear worldview emerges from their pages, a worldview that is decidedly right-coded.

Whether we believe the genre started with Forsyth’s The Day of the Jackal (1971) or reach back to Erskine Childers’ The Riddle of the Sands (1903), the core plot is always the same. The nation is under threat from external forces and the hero or heroes must take action to thwart them. The nature of the menace may change—for Edwardian Britons, it was Germany; in the seventies, it was shadowy assassins; in the eighties, Russian spies; most recently, Islamist terrorists—but the task of the protagonist is clearly conservative: he must preserve the status quo.

The Cold War provides the backdrop to much of Forsyth and Clancy’s earlier work. The Briton’s 1984 novel The Fourth Protocol depicts a Soviet attempt to engineer a change of government in the UK; the American’s Red Storm Rising (1986) envisages the Cold War turning hot. But the conflict merely provides an explicitly ideological gloss on the genre’s core assumption: our way of life is superior to that of others and must be defended. This reflects Michael Oakeshott’s definition of the conservative disposition as “acutely aware of having something to lose which [it] has learned to care for.”

This simple belief has allowed the genre to survive the decline of the Soviet Union, since geopolitics has continued to supply new enemies—Islamists, CCP operatives, even environmental terrorists, as in Clancy’s Rainbow Six (1998)—who want to impose their values on us. The American may have occasionally admitted that his country was not perfect but the solution that he outlines—when he elevates his hero Jack Ryan to the presidency at the end of 1994’s Debt of Honor—is not change but return. The accumulated taxes and regulations that were holding the country back are stripped away in a Reaganite fever-dream. These thrillers are not progressive: they operate from the underlying belief that progress is neither necessary nor possible. There is no better tomorrow to aim for, merely the possibility of a continued today.

In the genre, the state must be defended but it will often not be able to defend itself, the task being left to an individual. It is a staple that government, taken in the whole, is incompetent (Jack Ryan, a junior CIA analyst, is the only member of America’s intelligence community to understand that the captain of the Red October may be trying to defect); corrupt (an Air Force colonel passes on details of the hunt for the Jackal to his mistress); or malign (John Preston, hero of The Fourth Protocol, must be rescued by the head of MI6 from the purgatory to which the acting head of MI5 has pettily confined him ). If there are good bureaucrats in these books, they prove their bona fides, as in the above examples, by freeing the protagonists from bureaucratic restrictions.

Frequently, however, the task must be left to an external actor entirely. Quinn, hero of Forsyth’s 1989 novel The Negotiator, is an independent specialist in resolving kidnappings, Vince Flynn’s Mitch Rapp and Brad Thor’s Scot Harvath both work for private security companies.

However the individual is chosen, from the moment he is introduced to the plot, he must act either on his own, or with only a small, hand-picked team of allies. The resulting alliances may be one-offs, or the groups may become a recurring cast, as in Colin Forbes’ Tweed series and Daniel Silva’s Gabriel Allon novels but thrillers are not stories of mass movements or wide solidarity and, for the entirety of the crisis, the heroes’ contact with the government is generally kept to a minimum.

There is a separate genre of left-wing thrillers that are sceptical of state power, but these centre on government conspiracies, such as the Labour MP Chris Mullins’ 1982 novel A Very British Coup; the 1985 BBC series Edge of Darkness; and 1975’s Three Days of the Condor. Such novels, however, are generally produced when their authors’ ideological opponents are in power. It is only in right-wing thrillers that scepticism about the government is a constant. The Hunt for Red October was published during the final months of Ronald Reagan’s first presidential term.

The one exception to the genre’s distrust of the state’s abilities is the military, which is uniformly presented as competent and powerful. Clancy’s works are particularly notable for his idolisation of the armed forces. Ruled ineligible to serve due to poor eyesight, his novels often involve America being forced to project power against its enemies, allowing for long, loving descriptions of hardware, tributes to personnel, and, in some cases, unit histories. Forsyth had an obvious respect for Britain’s SAS (soldiers from the unit kill the Soviet agent in The Fourth Protocol and enable the destruction of the titular superweapon in 1994’s The Fist of God) but also for mercenaries, a legacy perhaps of his days as a reporter in 1960s Africa. The Dogs of War (1974) presents a favourable picture of a coup in a resource-rich state while The Negotiator treats with sympathy the former soldiers of fortune hired to kidnap the American president’s son.

Military power will, however, be applied unilaterally. There is no room in the genre for the United Nations, the International Criminal Court, or the rules-based international order. States act without compunction to protect their own interests. They may involve allies (Saudi Arabia and Kuwait join in the attack on the United Islamic Republic in Clancy’s 1996 novel Executive Orders) but not the international community, an entity whose existence the novels generally ignore. Nor are human rights and due process important. Executive Orders ends with the Iranian President being assassinated by a cruise missile, live-streamed during a televised address by Jack Ryan. At the end of Vince Flynn’s 2005 novel Consent to Kill, the antagonist, a Saudi prince, is killed by a phosphorus grenade—not extradited to The Hague. Those concerned about “rule by human rights lawyers” can find in thrillers a comfortable retreat to a Wild West-style world in which “some folks just need killin’.” The genre as a whole is a hymn to the “rough men… ready to do violence on our behalf,” allowing us to sleep soundly in our beds.

By necessity, the genre posits the ongoing competition foreseen by Samuel Huntington in The Clash of Civilisations and the Remaking of the World Order. The stable peace predicted by Francis Fukuyama in The End of History and the Last Man would not generate the large-scale conflict these novels require. Thrillers posit a Hobbesian bellum omnium contra omnes, in which nations and civilisations are in a perpetual war for dominance. Hard power is all. No government in a thriller would hand over sovereign territory in accordance with an advisory ruling by an international court or to increase its soft power. The concept would be incomprehensible to writers like Clancy and Forsyth.

Nor do these novels have any time for a technocratic governance that aims to regulate away all risk. Thrillers operate in a highly contingent universe in which random events have unforeseen and unforeseeable consequences. Detective novels are like a jigsaw—the end state (the crime) is generally known early on; the author then lays out the pieces and assembles them to form the expected picture. Thrillers, by contrast, lay out the pieces, but with no end state to guide the reader, we can only watch as the author constructs an unknowable picture. In The Devil’s Alternative (1979), Forsyth takes a castaway in the Black Sea, a broken valve in a Soviet factory, and a newly constructed oil tanker and weaves them into a crisis that will threaten the entire world. In Clancy’s Red Storm Rising, a terrorist attack in Azerbaijan leads to World War III as the Soviet Union invades Europe to secure its flank before striking out for the oil fields of the Middle East. Many of the stories illustrate Hayek’s argument in The Pretence of Knowledge that “To act on the belief that we possess the knowledge and the power which enable us to shape the processes of society entirely to our liking, knowledge which in fact we do not possess, is likely to make us do much harm.”

If complete knowledge of the system is impossible, knowledge of some of its parts is certainly within human grasp. Thrillers waste little time in debate or speculation, they are not novels of ideas or introspection, but they are novels of information par excellence, reflecting Oakeshott’s description of the conservative disposition as preferring “fact to mystery, the actual to the possible.” Forsyth undoubtedly deserves credit for this: his journalistic background instilled him with a passion for accuracy and detail. Copious research went into every novel. The method his antihero uses to acquire a passport in The Day of the Jackal was an admitted loophole in the system, which the British government finally closed three decades later. The porter and history tutor at the Oxford college he describes in The Negotiator are recognisably the porter and history tutor who were there when I attended it a few years later. Readers do not pick up thrillers to discover what the world might be or what they might be, but in the confidence that the author has done the work to tell them what the world actually is.

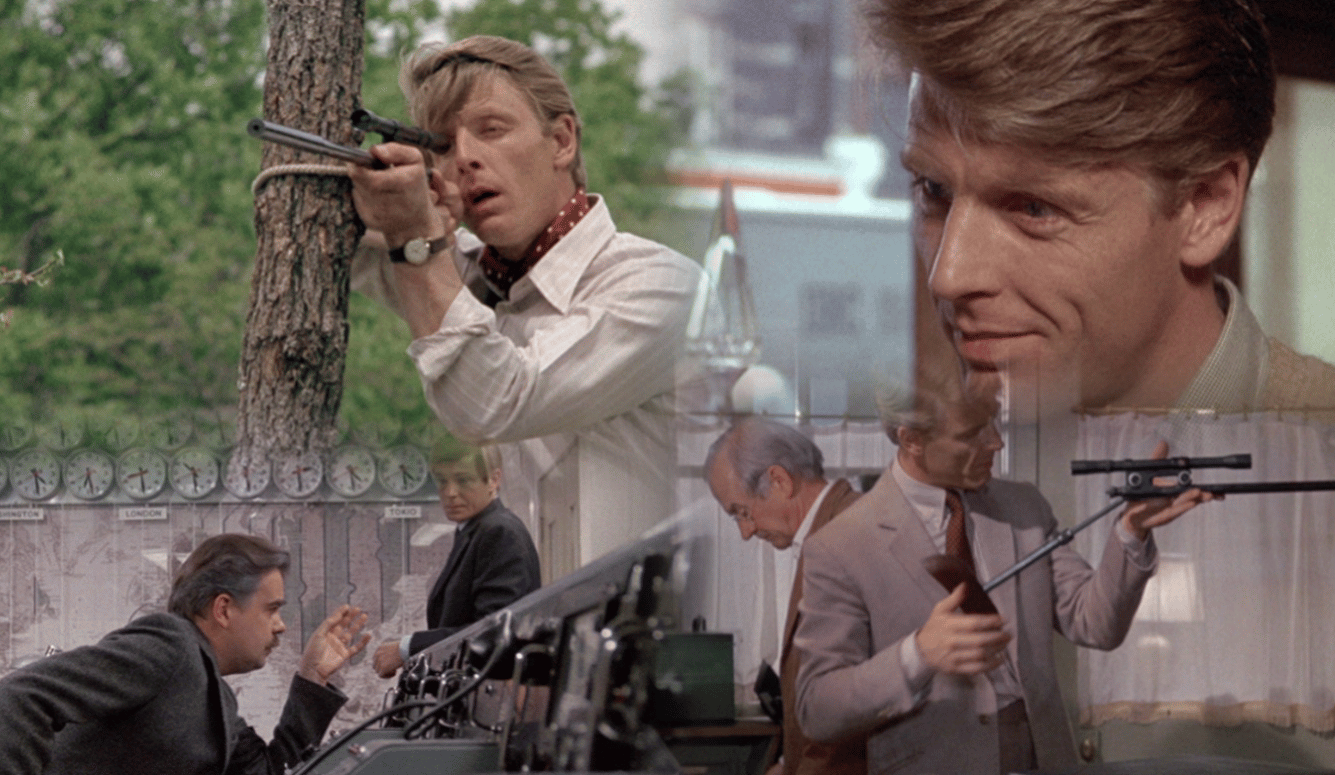

It would be easy to dismiss the genre as a low-brow form of literature destined for the remainder bin of history. But that would be unfair. The novels may not contain high-flown language, or lavish descriptions. If they leave a matter unresolved, it is to tee-up a sequel, not to give the reader something to ponder. But they are not unintelligent. The film critic Roger Ebert described Fred Zinneman’s adaptation of Forsyth’s debut as “put together like a fine watch.” The same could be same of the novel itself and of thrillers in general. The genre focuses on plot, with realistically described pieces moved meticulously around the chessboard to deliver an unsuspected checkmate.

But more than that, these novels are unique in that they constitute a purely right-wing art form. Ursula Le Guin used science fiction to express her progressive views, Robert Heinlein his libertarianism. Thrillers are not amenable to this. They require a conservative, realpolitik view of the world to generate their plots; they have an innate suspicion of government competence and a love of the individual. They exist in a world of nation states, not international bodies. They require the world to be unpredictable, but they love it for what it is, not what it might be. Politically, they convey neither doubt nor hesitation, but an unshakable confidence in the righteousness of the Western countries that produce them. Other genres can be adopted by Right or Left but geopolitical thrillers require a conservative sensibility to function. And that may guarantee they survive.